Donning the sale-high price of $52,500 was this elk skin jacket made by the Cheyenne people and owned by General George Armstrong Custer, which was later gifted to West Point army engineer Arthur McCall by Elizabeth Custer ($20/30,000).

Review by Kiersten Busch

DALLAS — “We were thrilled with the sale results,” shared Delia Sullivan, director of ethnographic art at Heritage Auctions of the firm’s William and Joey Ridenour Ethnographic Art, Western Memorabilia & Antique Firearms Signature Auction, conducted on September 13. “We saw very spirited bidding throughout each section of the sale: pre-Columbian, American Indian, Western memorabilia and arms and armor,” Sullivan continued. Offering 354 lots, the sale realized $850,580, with a 95 sell-through rate by value and 92 percent by lot.

William Ridenour, a lawyer and managing member of Ridenour Hienton & Lewis., P.L.L.C., and his wife, Joey, worked closely with Sullivan throughout the cataloging process. “The Ridenours invited me into their home three times to see and organize the collection. They were gracious hosts and easy to work with,” added Sullivan.

Of the bidding pool, Sullivan continued, “The participants included both regular clients (including dealers) as well as first time buyers. We experienced great crossover buying among the American Indian, Western memorabilia and arms and armor clients.”

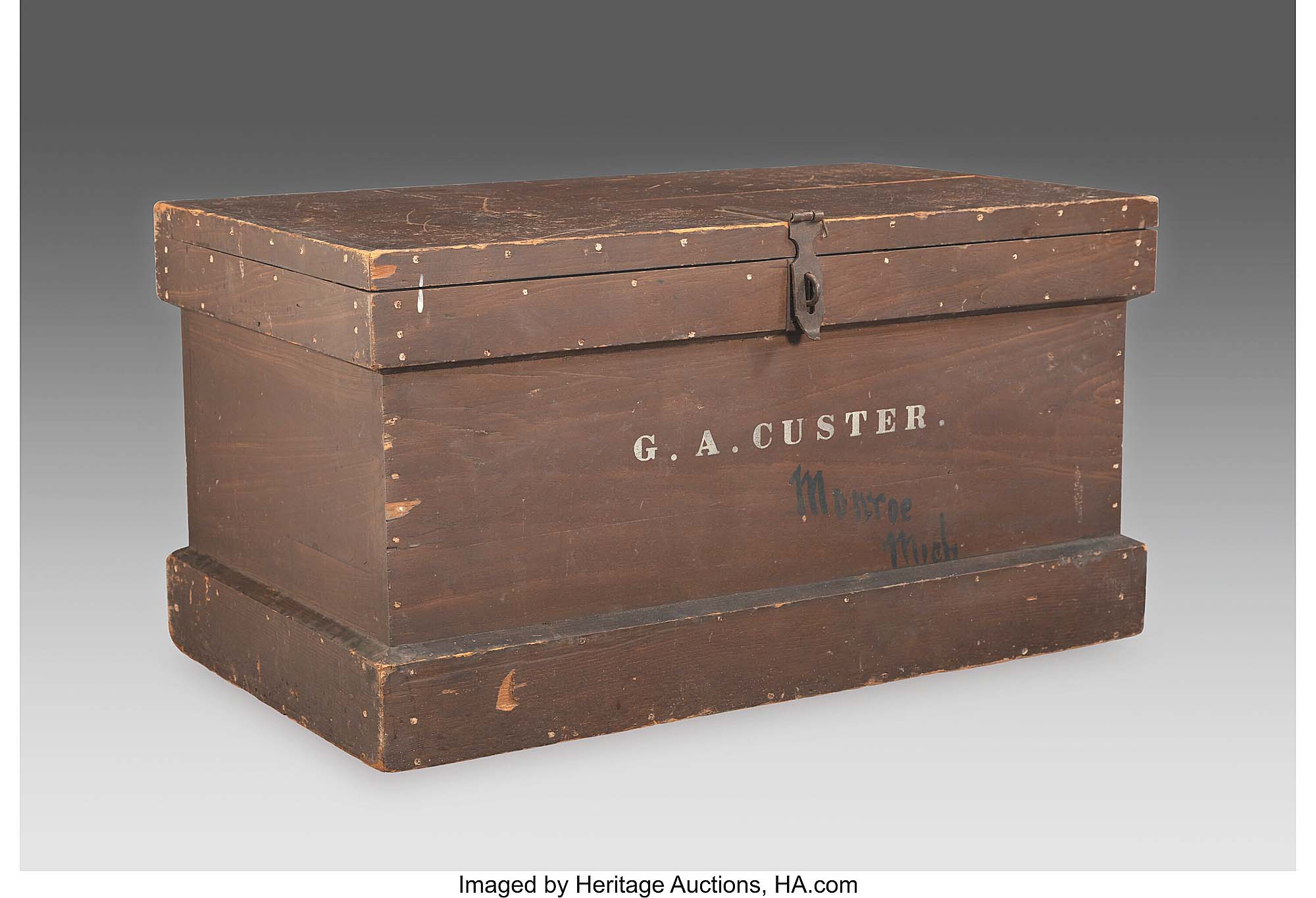

Besting its $15/25,000 estimate was General George Armstrong Custer’s personal Seventh Cavalry wooden footlocker, 37½ inches by 19½ inches by 21½ inches, stenciled “G. A. Custer” and marked “Monroe, Michigan,” which closed its lid for $35,000.

At $52,500, the highest-earning lot of the day was an elk skin jacket owned and worn by George Armstrong Custer, which was said to have been made for him by the Cheyenne, along with a pair of matching pants, which have since disappeared. In 1897, the jacket was acquired by a West Point army engineer, Arthur McCall, who was given the jacket by Elizabeth Custer, whom he had assisted in removing General Custer’s belongings out of storage at West Point. It then became property of the artist and historian Otto Gerhardt, then collector Greg Martin and finally, the consignor.

Another item belonging to Custer was the second-highest selling lot of the day. The General’s personal Seventh Cavalry footlocker, stenciled “G. A. Custer” in white on its front with “Monroe, Michigan” added below in black lettering, was “eventually purchased from the Custer Family by Dr Lawrence Frost, a noted Custer historian and collector,” according to catalog notes from a 1995 Butterfield & Butterfield sale, where the chest last sold for $30,250. In this sale, it reached new heights, closing shut for $35,000.

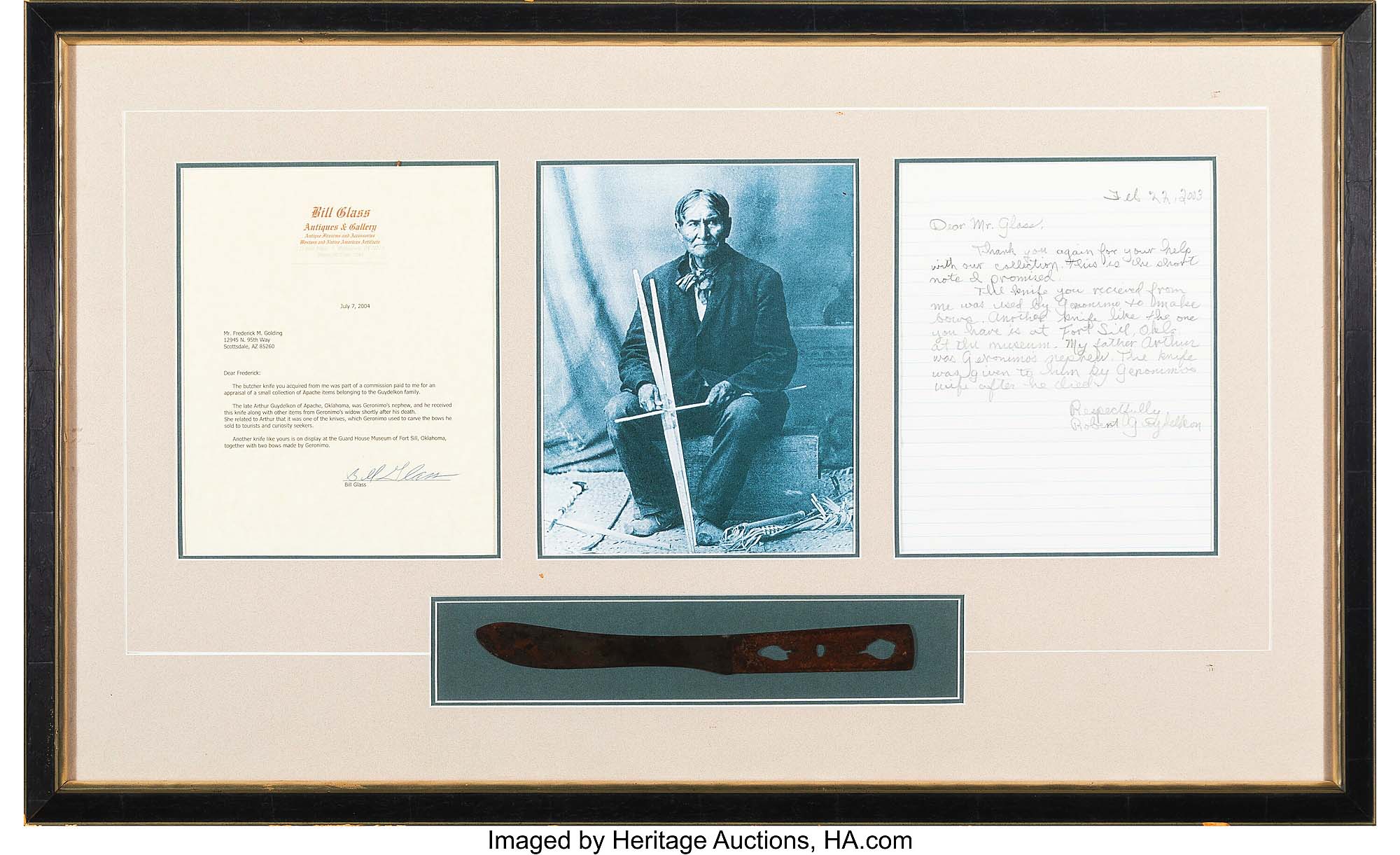

Other notable memorabilia included a 11¼-inch steel knife belonging to Geronimo, which sliced down a $10,625 finish. In a framed display case, the knife was accompanied by a modern copy image of Geronimo using the knife to carve a bow and two letters of provenance, one signed by Robert G. Guydelkon, who received the knife from Geronimo’s nephew, Arthur, and the other signed by antique dealer Robert Glass, who received it as a gift from the Guydelkon family.

Shooting down a $20,000 finish was this Winchester Model 1873 lever action rifle owned by Seventh Cavalry member Sergeant John Ryan. Manufactured in 1892, the .38 caliber rifle had a 24½-inch barrel with a fixed front sight ($4/6,000).

Firearms were led by a Winchester Model 1873 lever action rifle owned by Seventh Cavalry member Sergeant John Ryan, which was accompanied by a notarized statement of provenance from Ryan’s great-granddaughter. The .38 caliber gun — often called “The Gun that Won the West” due to its popularity with settlers, lawmen, outlaws and cowboys — had a 24½-inch barrel and was manufactured in 1892. Previously selling in Bonhams’ Antique Arms and Armor and Modern Sporting Guns sale in November 2008 for $5,265, the weapon more than tripled its value in this sale, shooting down a $20,000 finish.

Other firearms that performed well included a Smith & Wesson single action revolver with a beaded holster ($3,500) and a Colt Model 1860 army revolver with a period holster ($3,250).

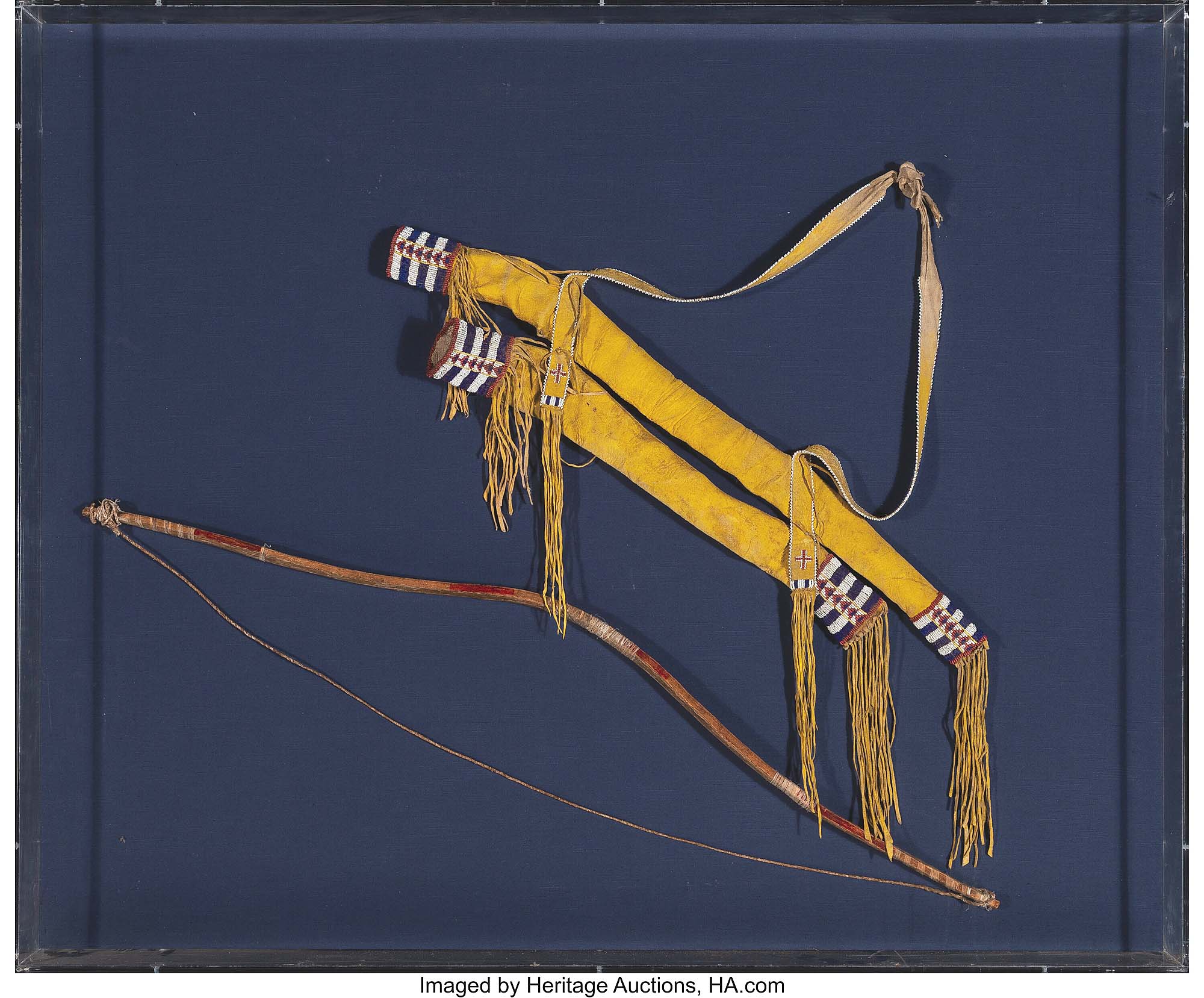

A much earlier weapon, the bow and arrow, was well represented in the sale, and had many examples from different Indigenous tribes earn high prices. A Cheyenne beaded hide bowcase and quiver with a recurved bow made circa 1880 led the group at $11,875. Both the bowcase and quiver were stained with yellow pigment and decorated on either end with sinew sewn glass seed beads, while the bow was rubbed with red pigment and strung with sinew. The lot’s provenance traced back to Midge Kellough of Miami, Okla., who was, according to catalog notes, “reportedly the eldest living member of the Peoria Tribe when she died in her 90s. Her third husband was Cheyenne.” An Apache beaded hide quiver, bow and arrows made circa 1890 ($8,125) also sold well.

This Cheyenne beaded hide bowcase and quiver with a recurve bow, circa 1880, shot a bullseye for $11,875 ($8/12,000).

Two items made by the Crow people earned high prices, including a beaded hide cradleboard, made circa 1900, which was cataloged as “rare.” Composed of wood, covered in hide and decorated with triangle motifs in various shades of glass seed beads, the 43-inch piece was raised to $13,750. The second Crow work was a circa 1890 rifle scabbard made with a thick hide decorated with panels of “classic Crow beadwork stitched in various shades of glass seed beads” which sliced down a $11,875 finish.

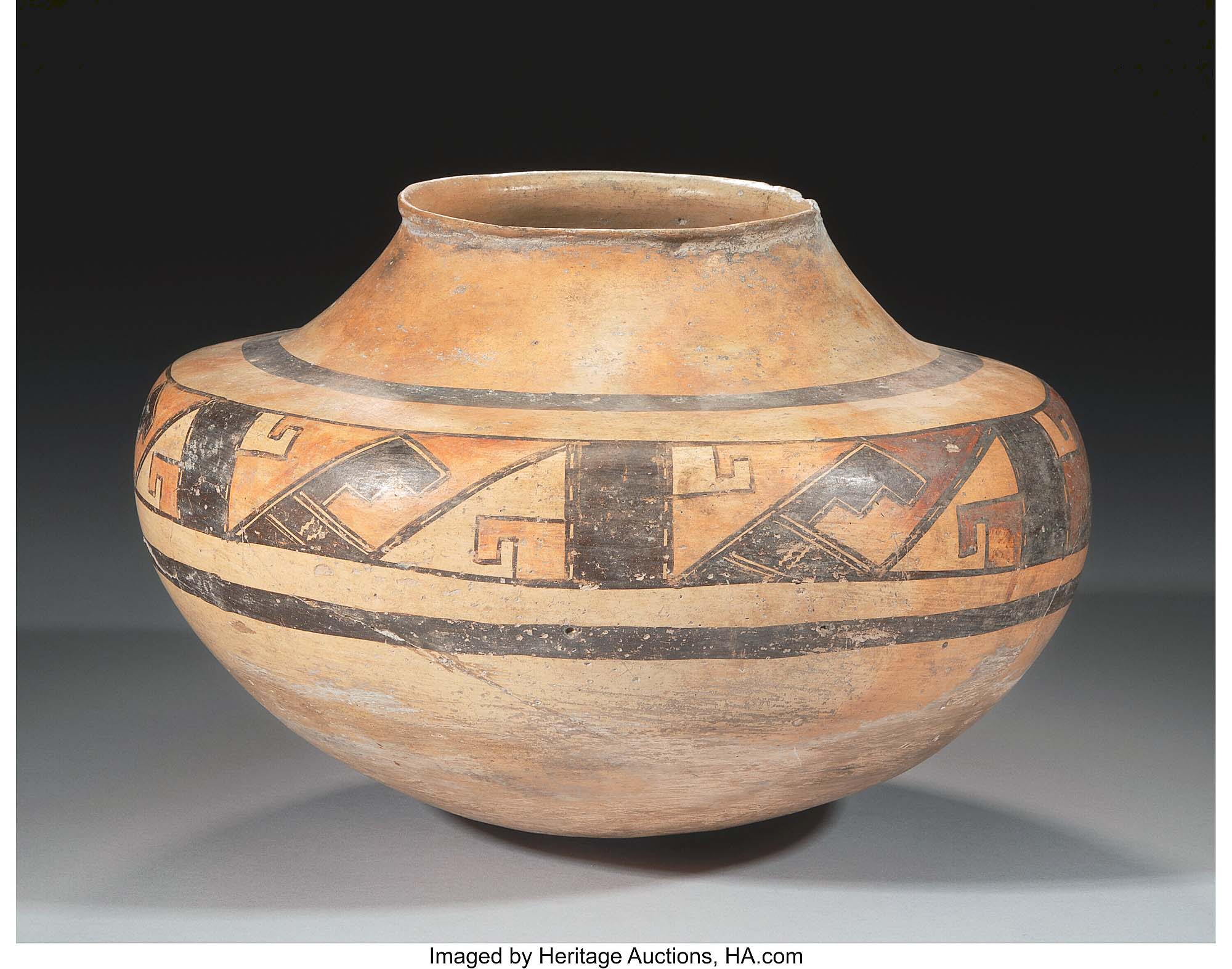

Pottery from various Indigenous cultures captured bidder attention, earning a large — 13¾ inches in diameter — Sikyátki polychrome seed jar $13,750. Sikyátki is an archaeological site and former Hopi village in Navajo County, Ariz., and this jar example was made in the village circa 1400-1625. Its pattern included a band enclosing geometric motifs painted in red and black, and it was inscribed “Volz Collection” on a sticker attached to its bottom.

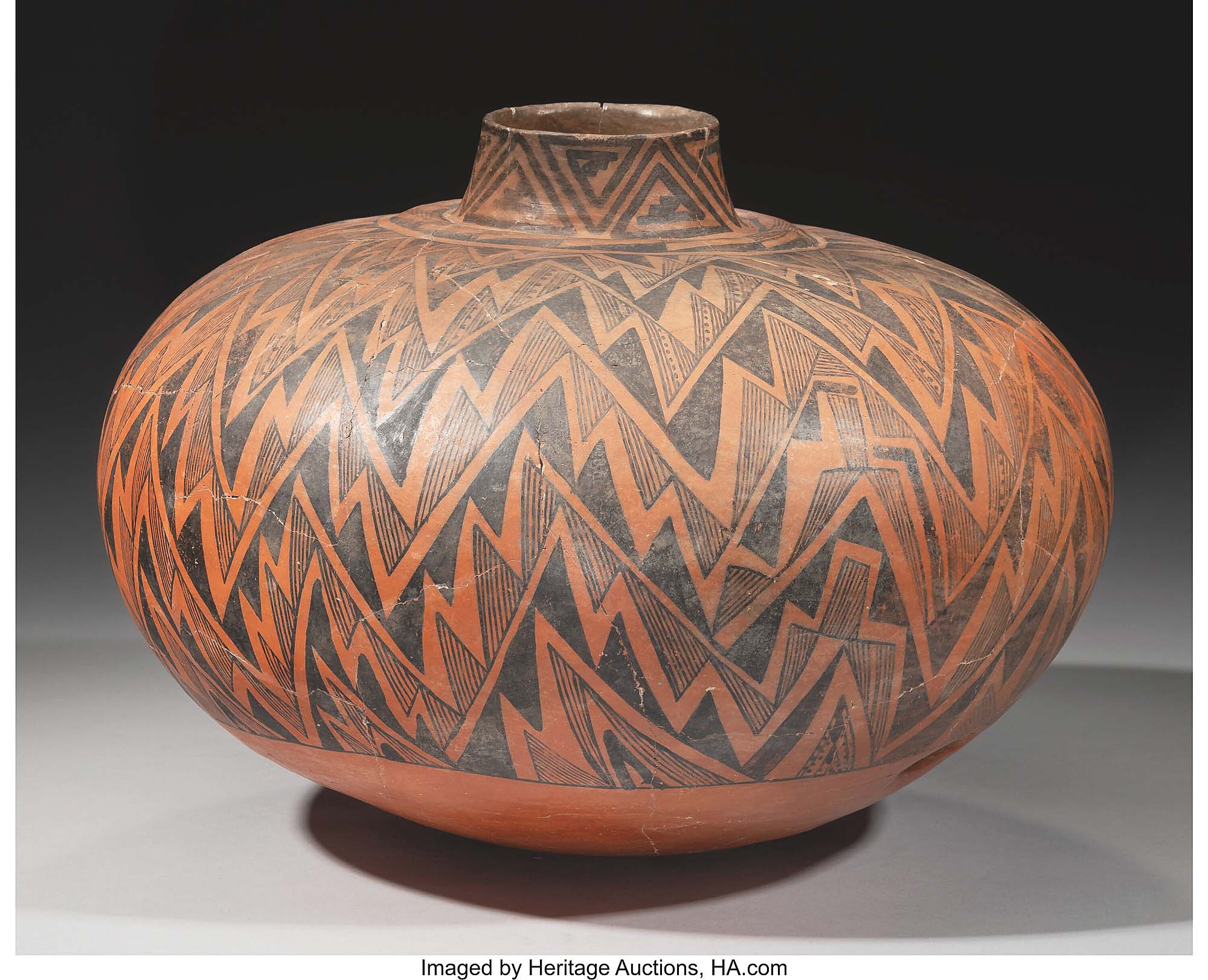

A black-on-red storage jar made by Indigenous peoples in Tularosa, N.M., circa 1000-1250 also performed well, topping off at $11,875. Cataloged as “a monumental example,” the jar measured 16 inches in diameter and was reassembled from numerous shards.

This Tularosa black-on-red storage jar, circa 1000-1250, 16 inches in diameter, almost doubled the high end of its $4/6,000 estimate at $11,875.

Indigenous sculpture was led at $9,375 by a pair of sculptures of a Nayarit couple made in Ixtlan del Rio, West Mexico, which dated circa 250 BCE-250 AD. Both works in the pair were made of hollow pink-orange earthenware and decorated with white and black pigments. Cataloged as “superb,” the pair were “remarkable, not only for their intact preservation, but also for being an engaging matched pair with a great sculptural presence, their adornments and garments counterpointing one another.”

Other sculptures that did well included a basalt Aztec figure of Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of water, fertility and childbirth ($6,250); an earthenware Maya/Toltec two-part acrobat vessel ($5,750) and an Inca Canopa, or alabaster ritual vessel, depicting a two-headed camelid ($4,500).

The Ethnographic Art department will have a single-owner sale on November 5 and another sale on November 6. For information, 214-528-3500 or www.ha.com.