Masterworks From ‘Unforgettable’ Artists At The National Museum Of Women In The Arts

Self-Portrait of Judith Leyster, circa 1630, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

By Z.G. Burnett

WASHINGTON, DC — The National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) is rewriting art history with its groundbreaking exhibition “Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750.” The Dutch version of this title begins with the word onvergetelijk, or “unforgettable,” cementing the importance of Dutch and Flemish women’s art and contextualizing its creators as integral, leading players in the local and global economies of this era. It addresses the myopic tendency in art historical scholarship to focus on only one group of artists and art, namely those that were white, male and patronized by the upper classes. Presenting nearly 150 artworks from 40 known and unnamed women artists, many are on display in the United States for the first time.

“There have always been women artists in every culture, in every era. The Seventeenth Century in the Low Countries was no exception,” explained exhibition curator and NMWA senior curator, Virginia Treanor. “[Contemporary] accounts from foreign travelers to the Dutch Republic frequently noted that women were accorded more autonomy than they were elsewhere. The extent of this autonomy, of course, was predicated upon the social status of the woman in question.”

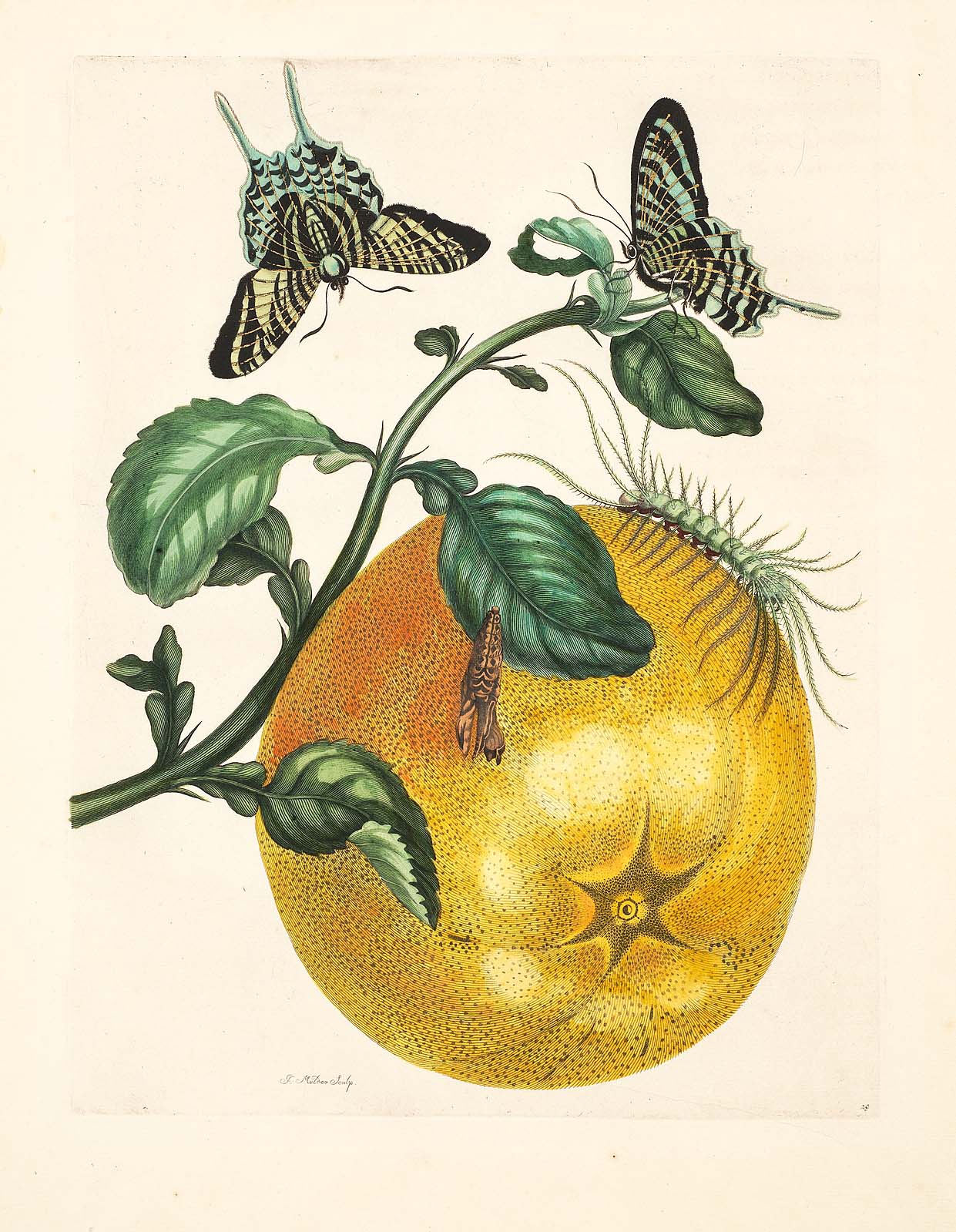

During the era formerly known as the “Dutch Golden Age,” the Low Countries (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) experienced unprecedented economic growth that led to a booming luxury market. This outdated term provides a romantic historical lens that filters out the source of these riches: rampant colonialism checked only by opposing European nations in pursuit of the same goal. Women at all levels of society both participated in and benefited from this system in some way, and their involvement with the region’s cultural economy cannot be overstated.

“Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge,” Rachel Ruysch, late 1680s, oil on canvas, National Museum of Women in the Arts.

“Many people are familiar with the male artists of this period, such as Rembrandt and Vermeer, yet few have heard of even the most prominent women artists who worked during this time,” said Treanor. “While there have been a few recent monographic exhibitions on [some], there has never before been a survey exhibition devoted to multiple women artists and diverse artistic mediums.” Rejecting the Renaissance-era bias that defined painting as the “highest” form of art, this exhibition showcases objects made by women whose names are lost to history. “It was important for us to demonstrate the breadth of women’s contributions in terms of genre… and materials.”

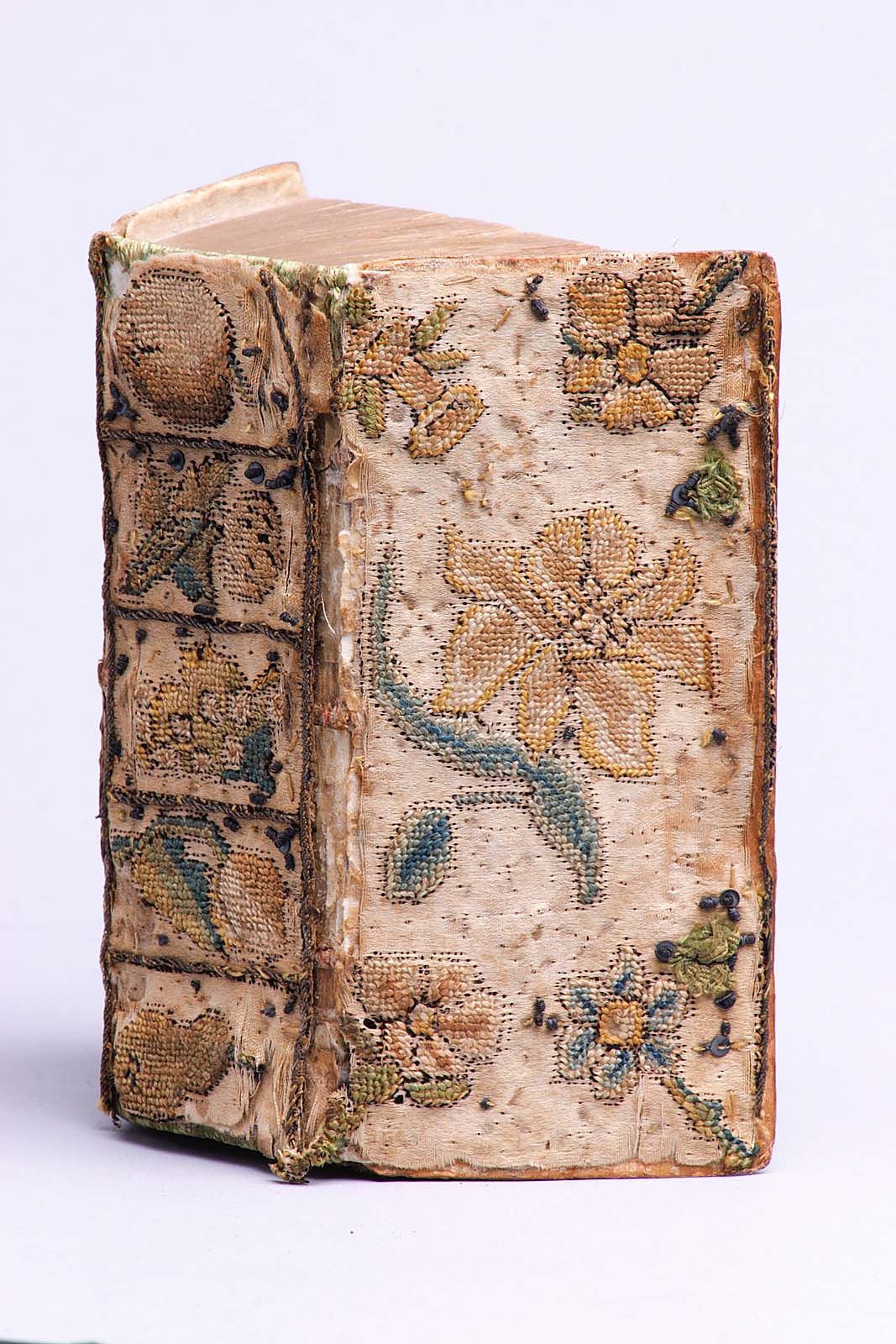

So-called “craft” objects such as paper-cutting, lacemaking and embroidery were highly prized and often more expensive than many paintings. Women excelled in these mediums but the aforementioned artistic hierarchies were also rooted in gender discrimination, so they were not considered “fine art.” Despite, or because, textiles were goods to be sold, they and the women who made them have long been overlooked for their cultural importance in the artistic economy of the region.

“Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750” is presented in four thematic sections. The first, “Presence,” demonstrates that women were honored participants in nearly all aspects of artistic culture of the era. Self-portraits were used by artists of both genders to display their talent, ambitions and identities. Judith Leyster’s self-portrait is one of the exhibition’s most well-known paintings, “a fantastic example of her signature loose brushwork, as well as being a really strong and confident statement about her abilities as an artist.” Leyster belonged to the painter’s guild in Haarlem, The Netherlands, allowing her to sell her paintings within the city, run a workshop of her own and train apprentices. This could not have been achieved without apprenticeship to a master painter early in life, paid for by her clothmaker-turned-brewer father. Leyster’s career exemplifies a woman’s ability to become a professional, successful artist, even if she was not raised in a family workshop.

Self-portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman, 1640, engraving on paper. National Museum of Women in the Arts.

The next theme, “Choices,” explores the decisions available to women in this period. Then as now, opportunities for artistic advancement varied greatly based on family connections and socioeconomic status. Anna Maria van Schurman was an acclaimed multidisciplinary artist and writer whose family was also wealthy enough to support her artistic ambitions. Becoming a wife and mother was the expected norm and often required for those who were not so well set up, and that decision made a profound impact on a woman’s life and work. Yet, it did not affect all women in the same way; for example, floral still life master Rachel Ruysch had at least ten children and a successful career that spanned six decades. Others needed to take on other work outside the home to support their growing families, encouraging their daughters to do the same.

This section displays a variety of textiles, including lace, embroidery and samplers, to illuminate the training that women and girls of all classes received. They were expected to learn sewing as part of their education, and those of a lower socioeconomic status could receive training in production of incredibly ornate and complicated textiles. “[Lace]… is so synonymous with the region, particularly Antwerp and Brussels,” said Treanor. “[It] was an incredibly costly luxury item and produced almost exclusively by women.” Lower class girls and women made lace in orphanages and reform houses, their reality in stark contrast with contemporary paintings of a solitary lace-maker in a quiet, domestic scene.

The theme “Economy” further illustrates the many ways in which women were integral to the economy of the Low Countries, demonstrating how female labor significantly drove the Seventeenth Century’s rapid expansion of trade that resulted in a thriving art market. However, understanding this economic reality requires an examination of the era’s ever-increasing globalization and the opportunities afforded by the growth of colonial trade, which included the exploitation of slavery and natural resources from stolen lands. As in other European countries at this time, Dutch and Flemish women were bound to support this effort in anonymity.

Self-Portrait of Maria Schalcken in her studio, circa 1680, oil on panel. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The exhibition concludes with “Legacy and Value,” which focuses on systematic marginalization of women artists over the past three centuries, tracing the disparity between their contemporary renown and the later obfuscation of their major accomplishments through misattributions to better-known male contemporaries or intentional erasure. In the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Leyster’s paintings were frequently misattributed to the painter Frans Hals or to her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer. Maria Schalcken’s signature on her self-portrait has a blank area before her last name, suggesting that her first name was painted over likely to attribute the work to her brother, Godfried. This was rectified in 2006.

The legacies that women artists and those in their circles worked to preserve are finally being honored with “Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750.” The exhibition provides a crucial reframing of this “golden” era, inviting female and female-identifying visitors to apply its lessons to today’s socio-political climate. “It is important to know the truth of women’s history, even though so much of it has been ‘forgotten,’ unrecognized or left out of traditional history classes; this exhibition demonstrates that women accomplished a lot during this time period,” Treanor believes. “Knowing what women accomplished then, and throughout all of human history, strengthens the belief and confidence of our abilities today.”

The National Museum for Women in the Arts is at 1250 New York Avenue Northwest. “Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750” runs through January 11, 2026. For information, 202-783-5000 or www.nmwa.org.