Theodate Pope Riddle launched herself into architecture design with the Hill-Stead Mansion. Upon its completion, she said, “This home seems strangely unreal to me. I feel as if I were walking in a dream and not in Farmington.”

By Kristin Nord

FARMINGTON, CONN. – Construction workers were already well into their shift as walkers took advantage of the sun-dappled trails on a beautiful spring morning at Hill-Stead; tulips were in bloom in the Sunken Garden and the fields were turning a lovely lime green.

If Theodate Pope Riddle’s vision was for this turn-of-the-century farm to be alive and accessible to the public in perpetuity, the current executive director and chief executive officer, Dr Anna Swinbourne, is a kindred spirit who has taken Theodate’s mandates and run with them.

Through her exploratory programming this past year, more people than ever have been taking in what this place has to offer, whether it’s a tour of the historic house, an evening of outdoor performance or a now-coveted seat at one of its farm-to-table al fresco suppers. Theodate and her parents conceivably oversaw similar gatherings during their years in residence. But in other ways, perhaps energetic leadership went a long way in the past year toward keeping the museum’s attributes and many charms accessible even during the months when the historic home was by necessity shuttered. Now that safety protocols are in place and tours have resumed, the institution is poised to embark on a new and improved era. No longer seen as a one-visit entry on a bucket list, this institution has become a major cultural destination.

_(1)_(1).jpg)

On nearly an acre, Hill-Stead’s sunken garden features brick walkways, boxwood and more than 90 varieties of annuals and perennials. Theodate Pope created it for her mother, Ada Pope, in 1901. When the garden was restored in the mid-Twentieth Century, a plan was discovered that was produced for the property by Beatrix Farrand, a successful landscape designer of the first half of the Twentieth Century. The garden was then restored with a modern interpretation of Farrand’s original plan.

Hill-Stead was envisioned as a ferme ornée, or ornamental farm, by the daughter of the wealthy Cleveland industrialist family who had agreed to retire to this beautiful property to be near to their beloved only child. As if to trumpet her goal of becoming a practicing architect, the young Effie had taken a much more elegant name, Theodate, from her grandmother. With her father’s blessing, she informed the prestigious New York City firm of McKim, Mead & White, the foremost architectural firm working in the English Colonial Federal Revival style and the one hired to oversee the project, that she intended to shepherd it under their auspices. “As it is my plan,” she informed them, “I expect to decide in all the details as well as all more important questions of plan that may arise. This must be clearly understood from the outset. In other words, it will be a Pope house instead of a McKim, Mead and White [one]”. This was not the first of such barriers to women that Theodate would challenge. She had already completed a self-directed apprenticeship in which she had mastered the rudiments as she oversaw the renovation and redecoration of another historic home just minutes away.

To prepare for their move to Farmington, the family had shopped for furniture, carpets and draperies in Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. Their rooms would be a mix of antique and period reproduction furniture and Georgian Colonial Revival woodwork.

Theodate designed interiors to suit her parents’ style of living, with communal areas that functioned as formal reception rooms for an illustrious cadre of visiting friends. And they would be entertained in rooms that showcased some of the most important recent works of art to be found in this country.

A view of the paneled environs within Hill-Stead reveal antiquarian bindings, horological specimes and more. Caryn B. Davis Photography.

By 1901 the house was ready for occupancy, but it would take until 1906 for the project’s final modifications. In many ways, James F. O’Gorman writes in the catalog on the museum, the rambling layout was inspired by the traditional New England farmsteads “that had been rediscovered and prized since the time of the Centennial Exhibition of 1876.” Theodate would go on almost immediately to design Westover, the boarding school for girls, and later, Avon Old Farms School, as well as The Hop Brook School in Naugatuck. And in her domestic architecture commissions, O’Gorman notes, she continued to draw upon the ideas of British designers, including Charles F. Annesley Voysey and Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

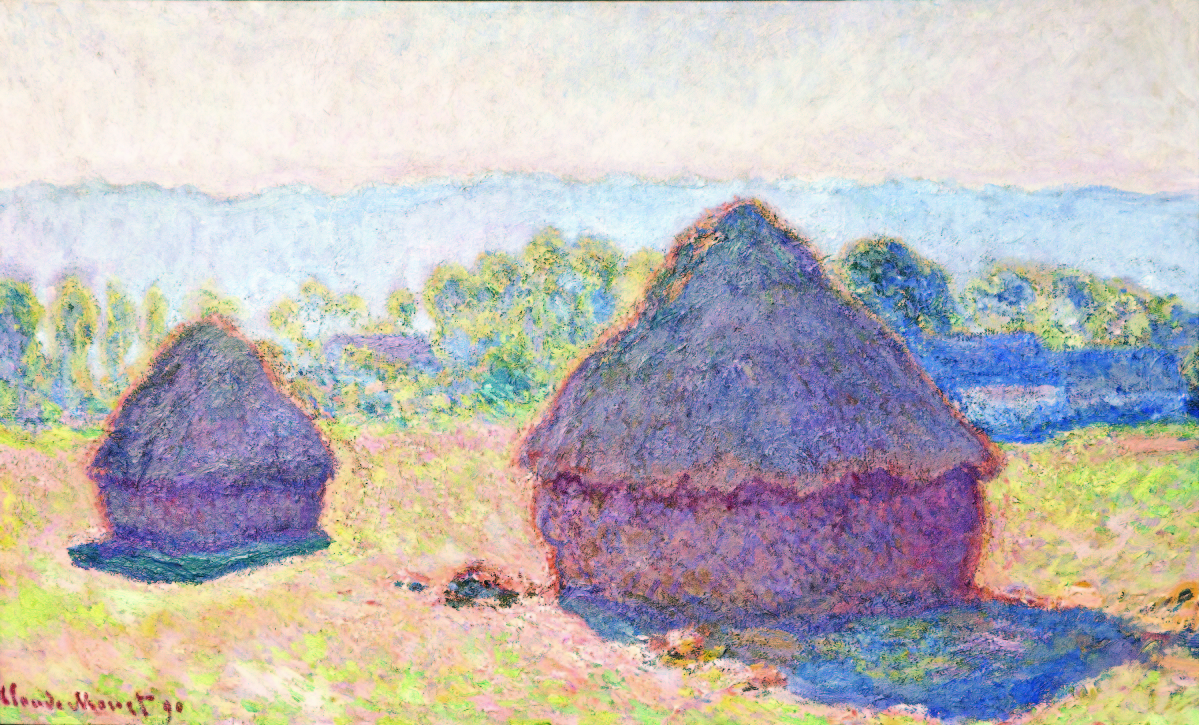

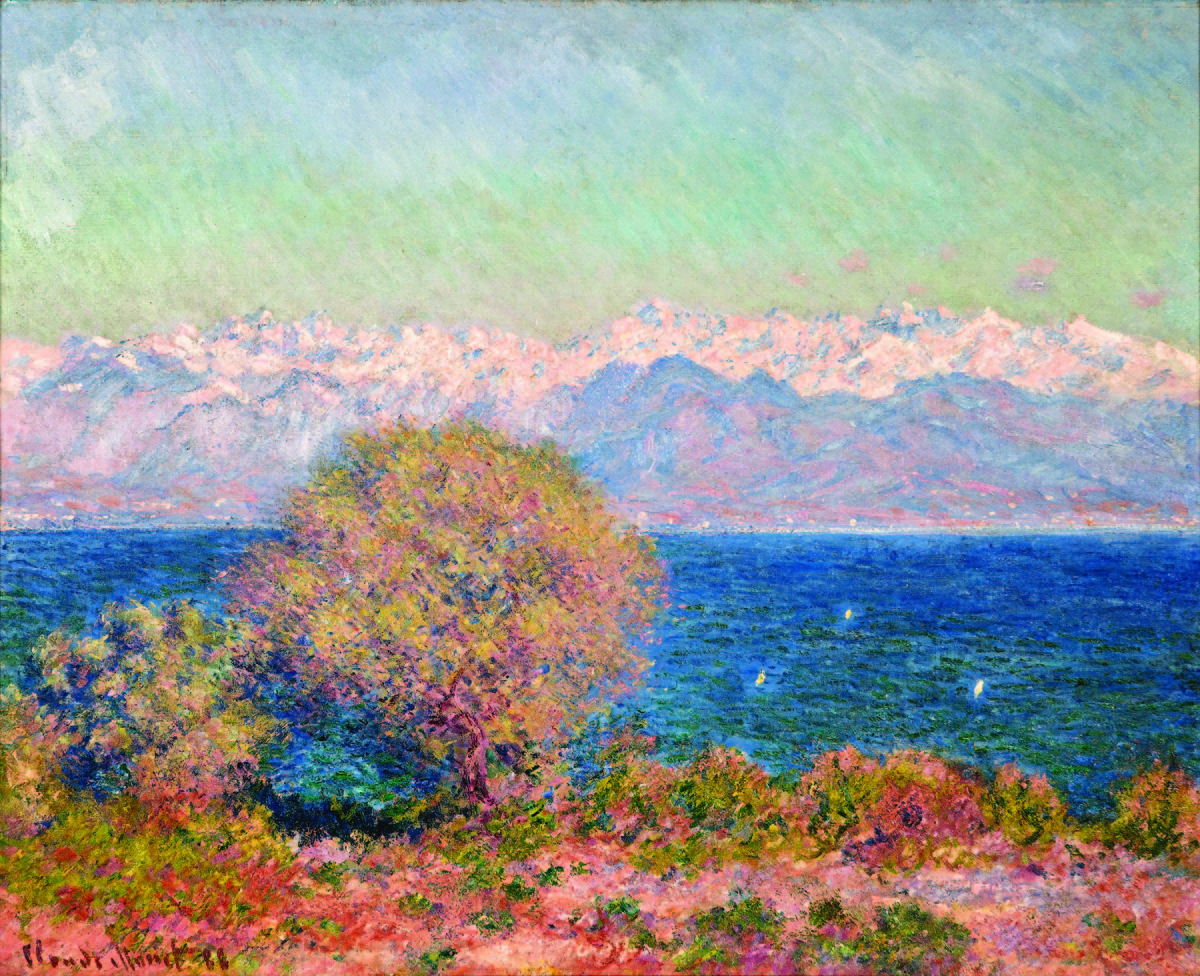

Art was her father’s, Alfred Atmore Pope’s (1842-1913), passion, and he amassed a major collection of Impressionist paintings between about 1888 and 1907. He bought viscerally, and if he lost interest in a work, he would winnow it from his collection. Today, the contents of the house include important works by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883). Each became focal points in Hill-Stead’s rooms, and the colors in their compositions were repeated in a room’s furnishings.

The blues, greens and yellows in the Italian majolica garniture, for instance, displayed just below one of Monet’s “Grainstacks” brought out the same hues in the artist’s brush strokes. Similarly, upholstery fabric echoed the soft pinks of the ballerinas’ tutus in Edgar Degas’ depiction. More than a century later, these interiors still feel sumptuous and comfortable. No wonder Henry James and Mary Cassatt liked to visit.

Alfred Pope (1842-1913), the patriarch of the Pope family and a self-made industrialist, became one of the foremost collectors of world-class Impressionist art contemporary to his time.

As the art historian Anne Higonnet puts it, Hill-Stead enables us to see Impressionist paintings as they were meant to be seen – in these domestic settings.

Additional collections of Asian ceramics and majolica were strategically placed to intensify the experience of color… And Theodate proved a stickler for details in other ways, from the butterscotch-color grained wood that runs like connecting thread throughout the house to the height of the window sashes to accommodate her father’s 5-foot-11-inch stature.

Outside was Mrs Pope’s sunken garden, with its boxwood, simple geometric patterns and its cottage flowers, very much in the Colonial Revival style as well. Simplicity, consistency and repetition were predominant goals, and to this day, there is a cohesiveness that underscores its restorative mission.

Upon its completion, “This home seems strangely unreal to me,” Theodate confessed. “I feel as if I were walking in a dream and not in Farmington. It all seems so unlike the Farmington I have always known…but it is all so very restful and beautiful. I feel so at peace with the accomplishment of it.”

Though Hill-Stead has no receipt for Mary Cassatt’s “Sara Handing A Toy to the Baby,” circa 1901, they believe it to have been acquired circa 1902. Records from the Durand-Ruel archives in Paris indicate it was purchased from them at that time.

In this art-filled museum, it’s impossible to absorb all that it has to offer in a single visit. In the months ahead, with the completion of a $6.9 million Capital Improvement project, on the footprint of what once served at the Pope’s carriage barn, new gallery space and a new interactive media center will enable Hill-Stead curators to excavate from a deep well of archival material. With the Connecticut firm Centerbrook Architects and Planners’ masterful adaptation of the carriage barn, Swinbourne and staff will have the freedom to execute ongoing exhibitions that will tap into not only the Pope family’s personal history, but will examine the social history and women’s issues from Connecticut’s Gilded Age.

“Exploring the many treasures and wealth of Hill-Stead’s collection is precisely what is planned for the renovated Carriage Barn spaces, both in the art gallery and new media space. The ability to tell the story in a more complete and compelling fashion is, in fact, a major motivation behind the endeavor to create space for temporary and rotating programming – a complement to the diametrically fixed nature of the displays and installations of the historic home,” Swinbourne commented recently.

Upcoming exhibitions will include one that reunifies the Pope family’s fine collection, while another part of a series, titled “Strong Women,” will look at Theodate’s contributions as well as those of other prominent historic women who forged unconventional careers. The new exhibition hall will also open the possibility of exploring Pope’s other collections, whether the prints by such artists as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Whistler, or Pope’s extensive collection of Ukiyo-e prints, featuring celebrated artists Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), Suzuki Harunobu (1724-1770), Kitagawa Utamaro (1750-1806) and Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858) that once hung in the master bedroom.

A sunset lingered over Hill-Stead during an act from the museum’s “From the Porch” performing arts series.

If the pandemic forced Hill-Stead leadership to brainstorm, the end result was programming that has drawn new audiences and new families. This is no longer a place that people will visit just once and check it off their bucket list. One has to imagine Theodate endorsing this as a modern-day articulation of her will’s stated wishes.

And the museum will build upon its great success with last summer’s “From the Porch” performance series as it partners with many leading Hartford performing arts institutions.

Interestingly, Robert A.M. Stern, the former dean of the Yale School of Architecture, likens the temperaments of Theodate and Frank Lloyd Wright, two contemporaries who drew from the same cultural well but veered off in distinctly different directions. While Wright mythologized the prairie on his own artistic terms, Stern notes, Theodate embraced the New England vernacular, not to reinvent it but to explore its nuances. That this wealthy woman was able to challenge conventions and to achieve such success in her field is a story worth probing.

What better way to revisit this story than to revisit Hill-Stead, where this woman master-builder got her start? What she achieved here, Stern notes, was the creation of a home that “to a remarkable degree, is both monumental and informal – no trivial accomplishment. It is a mansion and a farmhouse. Most of all, it is a quintessentially American house.”

Hill-Stead Museum is at 35 Mountain Road. For more information, www.hillstead.org or 860-677-4787.

.jpg)

.jpg)