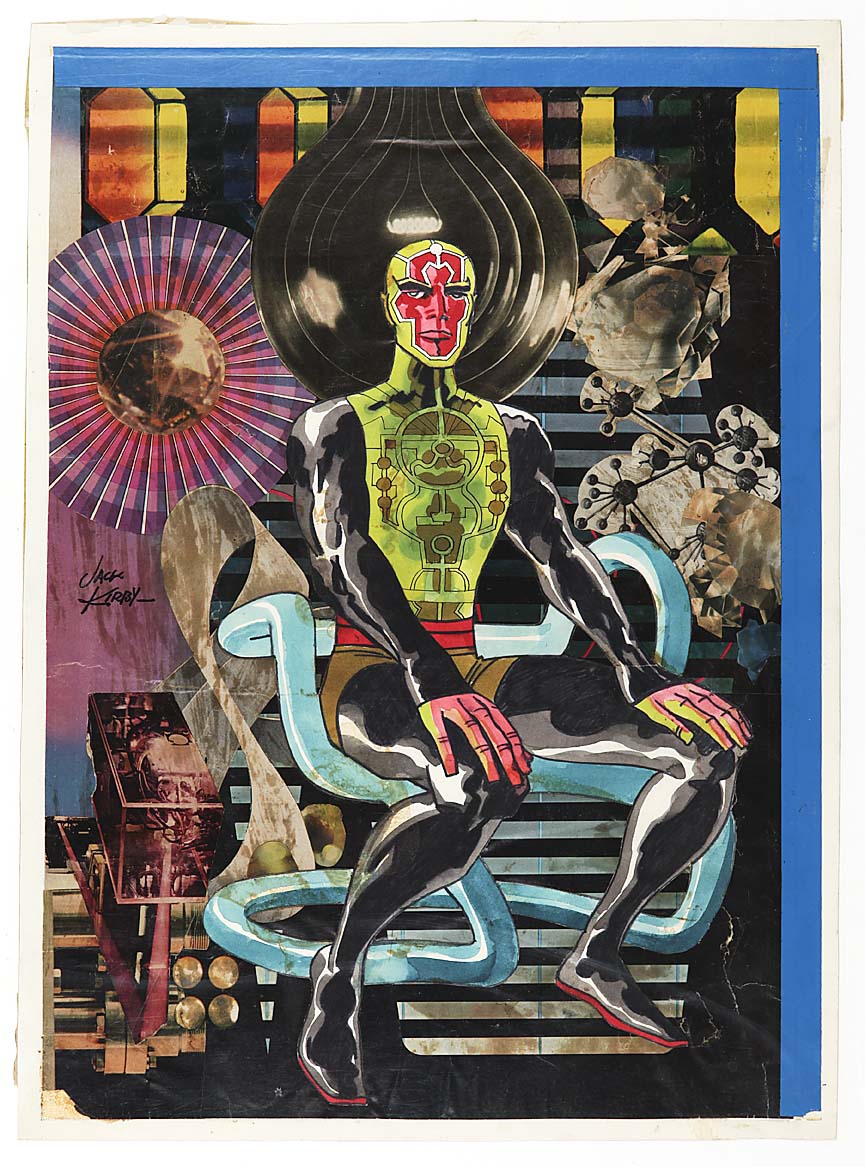

“Metron” unpublished character design by Jack Kirby, circa 1970, pencil, ink, collage and watercolor by Jack Kirby. © DC Comics.

By James D. Balestrieri

LOS ANGELES — In those years, the between years, the years of freedom, BG — “Before Girls” — I was one with my bicycle. The shadow my lime green 10-speed Schwinn and I cast, like something out of a Robert Vickrey painting, etched itself on the asphalt and raced me wherever I rode. On Wednesdays in the summers, when it always seemed to be summer, I would bike with my buddies to The Turning Page, the first store in Milwaukee that specialized in comic books. Wednesday was new release day. That narrow sliver of life coincided with the close of the Silver Age of Comic Books, when Stan Lee, Gil Kane, Steve Ditko, John Buscema — and Jack Kirby — among many others, brought Captain America, Superman and Batman back from post-World War II purgatory while creating new heroes like Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four. My buddies and I would make what purchases we could with our allowances and whatever we had earned and failed to squander elsewhere.

I have to admit, I wasn’t all that hot on Jack Kirby back in the mid 1970s. My tastes ran to fantasy and the weird: the anti-hero Killraven in Amazing Adventures’ War of the Worlds; the brooding, reluctant king of Valusia, Kull the Destroyer; the haunted Jack Russell in Werewolf By Night. And Spider-Man, naturally. Afterwards, we would go next door to Van’s Bakery for sweet rolls: eclairs, crullers, cream- and jelly-filled marvels, we would eye them all up, debate and choose one each. I was an elephant ear fan. The large, flat, flaky swirl with nuts and some sort of maple caramel tucked in the folds eclipsed all other sweet rolls. And then we would find some shade and try not to sticky up our comics with melting sugar — sugar made the pages stick, and if the pages stuck, well, that was “Goodbye, Charlie!” for Killraven or Kull or Jack or Peter Parker or Steve Rogers, who wasn’t my guy, at least not until Chris Evans started playing him. I can hear a voice back then, but can’t recall which, laughing and saying, with a delicious oily sarcasm, “Hey, cool guy, your elephant ear flakes are blowing all over my Captain America!” and another voice, I can’t recall which, saying, “Goodbye, Charlie!” and another voice, I can’t recall which, saying, “Goodbye, Steve!” and another voice, maybe mine, saying, or thinking, “At least until next Wednesday.”

Installation of “Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity” at the Skirball Cultural Center.

My buddies were the ones who brought copies of Mad and Cracked and National Lampoon and Famous Monsters of Filmland — which began hinting early on at an upcoming film by someone named George Lucas called Star Wars — to school. They could all draw comic book characters extremely well and, at times, let me orbit at a distance around their alien world, a world I had not known before. I drew too, but my aesthetic ran only as far as vintage film noir cars and planes, old planes — Sopwith Camels, Spitfires and Hurricanes, Mustangs and Corsairs — and jets — Shooting Stars and Delta Daggers and Phantoms, not to mention the improbable fantasy craft that sprang from my own invention. The soundtrack? Edgar Winter’s “Frankenstein” and the “oooga-chakas” in “Hooked on a Feeling.”

Before embarking on this essay, a look at the astonishing (there’s a comic book word for you) and celebratory exhibition “Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity” at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, I went through my comics. Yes, I still have them. I mean, come on, I write for Antiques and The Arts Weekly, so of course I still have them — along with my other collections — much to the chagrin of others who do not appreciate their value (which, in fairness, always turns out to be more sentimental than pecuniary). Yes, my comics are properly bagged and boarded now. Fewer than you might expect have elephant ear sugar on them. No, I haven’t had them graded. It doesn’t matter.

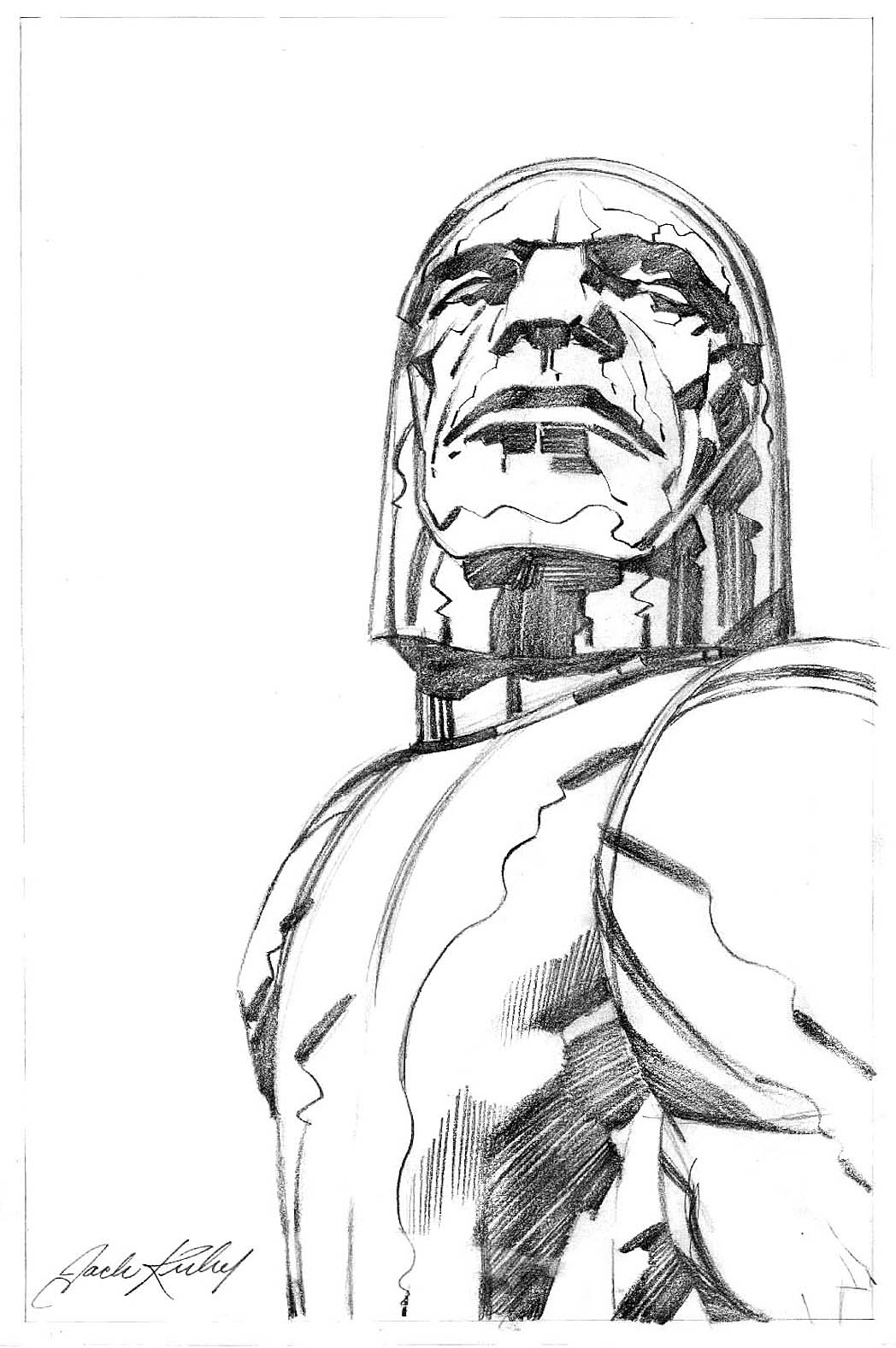

“Darkseid” by Jack Kirby, circa 1971, pencils. © DC Comics.

I found three comics with Kirby art: Thor #154 and Ghost Rider #22, with Kirby’s cover art. The third Kirby takes me back — Black Panther #1, purchased for the princely cover price of 30 cents in January 1977. Kirby had left Marvel in 1970 after a dispute over payment and copyright with Stan Lee (these disputes would persist to the end of his career and life). And yet, here he was, back at Marvel seven years later, writing, penciling and inking the first standalone Black Panther, telling a tale of the heroically cool T’Challa (played in the films by the equally cool, late great Chadwick Boseman) Prince of Wakanda, an Afro-futurist paradise hidden from view in Africa. In Black Panther #1, T’Challa fights wealthy collectors killing one another to control time itself, even as their oligarchic greed unleashes death across eons.

A few months later, Star Wars would hit theaters and upend the worlds of sci-fi, superheroes, fantasy and sword and sorcery in one fell swoop. Issue #1 of the Marvel comic book adaptation hit The Turning Page a month or two prior. Yes, I still have that one too, complete with green Darth Vader on the cover; aspects of the film were shrouded in secrecy.

“Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity” reminds the visitor of just how much Kirby contributed to all of this: to new, psychologically complex superheroes who nevertheless knew and fought evil when they saw it; to the mainstreaming of the comic book and its elevation from dime pulp to art form; to the transformation of the Saturday matinee serial to studio blockbuster; and to the evolution of the comic book fan from kid to grown-up kid, one who still collects comic books while dreaming of fighting big bad guys on behalf of all those who need help.

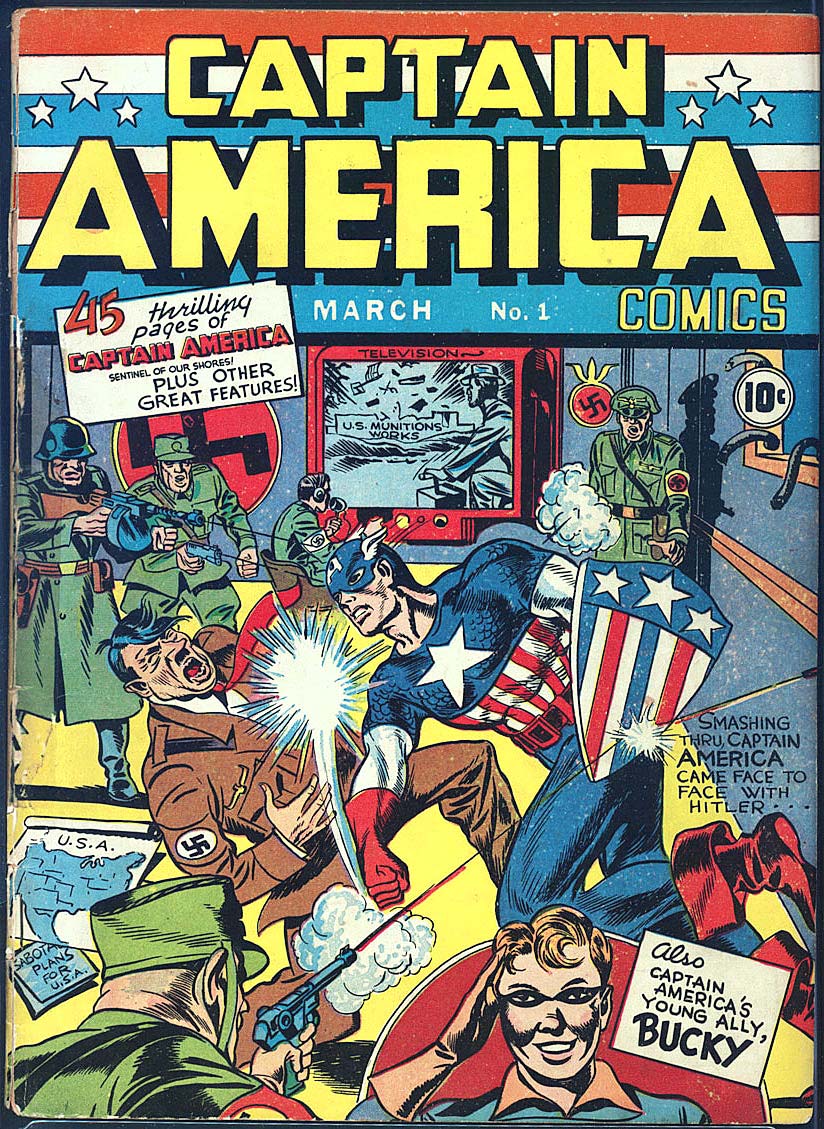

“Captain America Comics #1” cover art by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, 1940. © Marvel.

The exhibition starts where it must, with Jacob Kurtzberg, born in 1917 in the working-class Lower East Side of Manhattan to Jewish immigrant parents. It goes on to his first job as an artist, with Fleischer Studios, home of Betty Boop and Popeye. In the wake of the appearance of Superman in 1938, and against the wave of antisemitism that was sweeping the United States — and had a stronghold in New York — Jacob Kurtzberg becomes Jack Kirby in 1938. Working for Timely Comics (which would become Marvel), in 1940 and 1941, prior to America’s entry into World War II, Kirby’s cover for Captain America #1 features Cap punching Hitler in the nose while Captain America #5 pits Cap and his sidekick Bucky against the pro-Nazi German-American Bund’s rally in Madison Square Garden — a rally that had really happened — yes, it can happen here — two years earlier, in 1939.

Kirby’s time in the US Army, from his landing in Normandy through his service on the front lines in Europe, seems only to have deepened his hatred of fascism, bigotry and war, but on his return, he found that the market for comic books had changed. He and his partner, Joe Simon, with whom he had worked on Captain America, created comics that served the postwar sensibility — romances geared for young women, lurid crime stories, white hat/black hat Westerns and monster-centered horror. The advent of television, as well as government investigations into the supposed immorality of comic books led to a decline in sales through the 1950s.

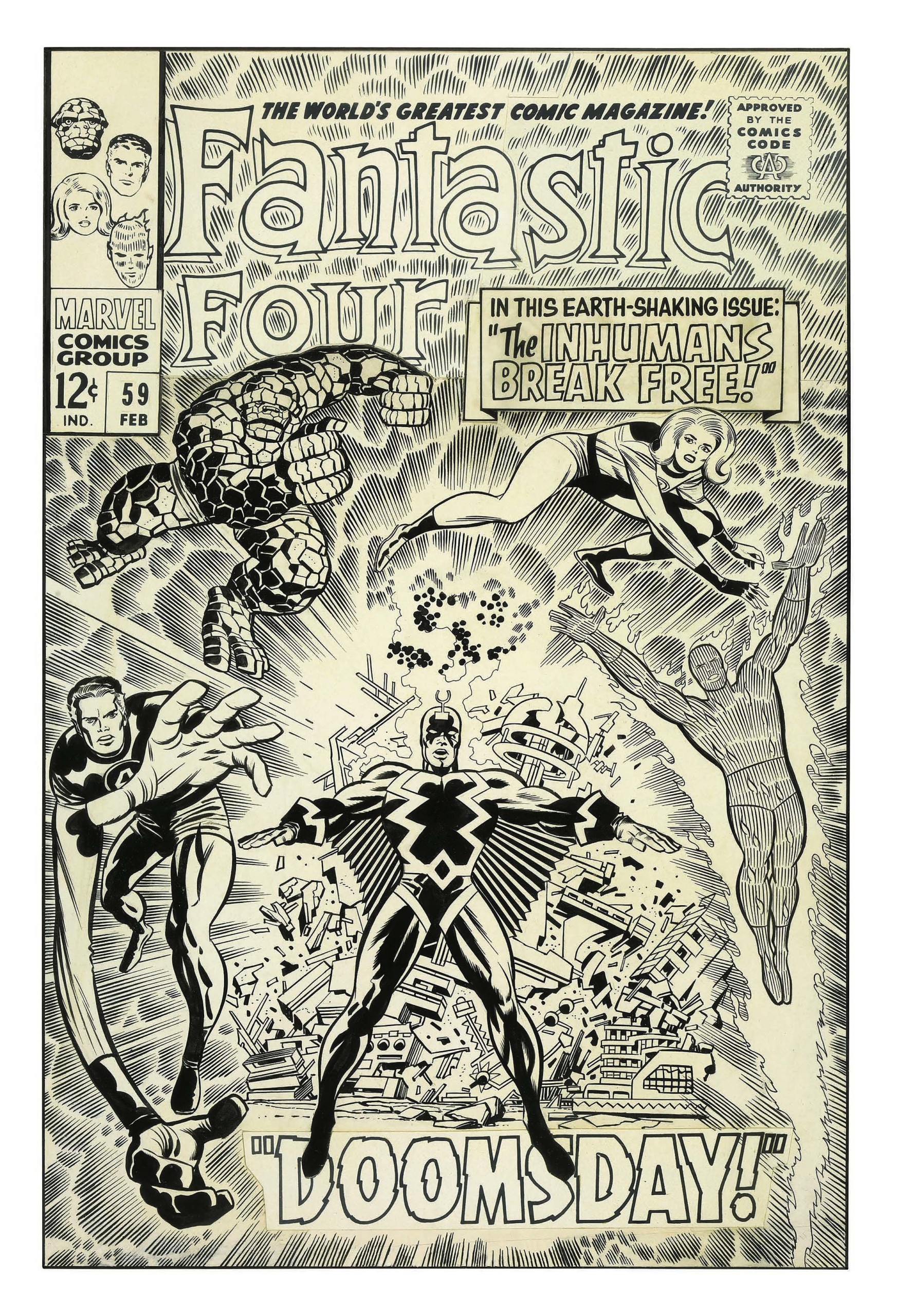

“Fantastic Four #59” by Jack Kirby, 1967, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Joe Sinnott. © Marvel.

By 1960, with the space race in full swing, Kirby, Stan Lee and others at Marvel and elsewhere saw new opportunities. The first of these, for Kirby, was Fantastic Four, a title which was (and is, as the ongoing comics and newest film adaptation this summer attest) part science fiction, part soap opera. We read — and/or watch — genius Reed Richards “Mr Fantastic” negotiating his marriage with Sue “Invisible Woman” Storm while they, along with Sue’s brash brother, Johnny “the Human Torch” Storm and the tormented man of stone, Ben “The Thing” Grimm, marry space travel and save-the-universe battles against supervillains and alien invasions with the imperfections of family life and the pitfalls that come with celebrity.

Through the 1960s, Kirby would create or help create a whole cast of characters that have entered the zeitgeist: the Hulk, X-Men, Ant-Man. Kirby would find new source material in Norse mythology and add Thor to the roster that would join the renewed Captain America and Iron Man with Black Widow, Hawkeye, Captain Marvel, Doctor Strange, Black Panther and a host of terrific villains in the box office smash hits that begin with Iron Man in 2008 and conclude with Avengers: Endgame in 2019, through the spinoffs, sequels, prequels and stories on alternate timelines in alternate universes branch and float off to this day, like bubbles of quantum spin foam on the lip of an infinite god.

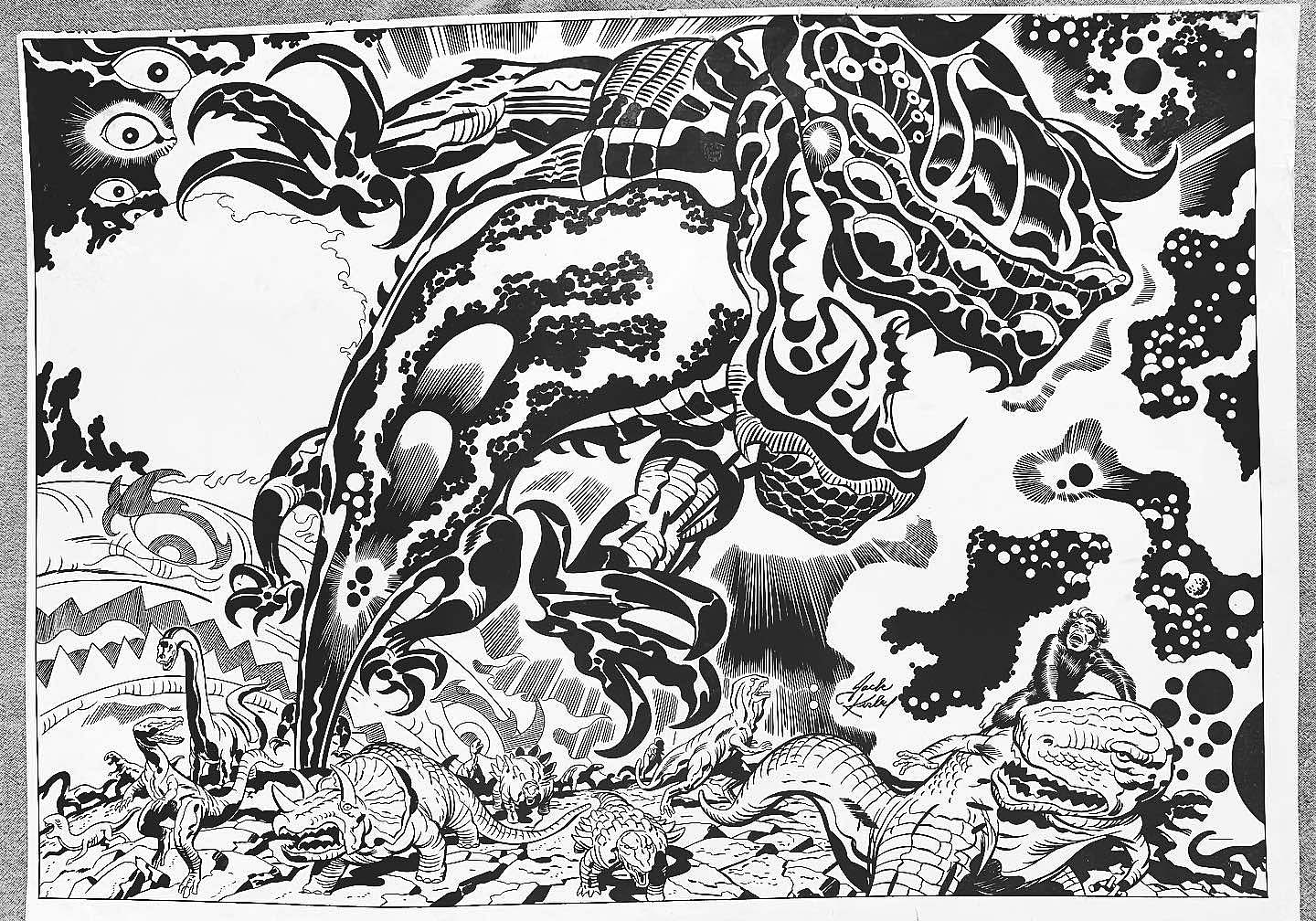

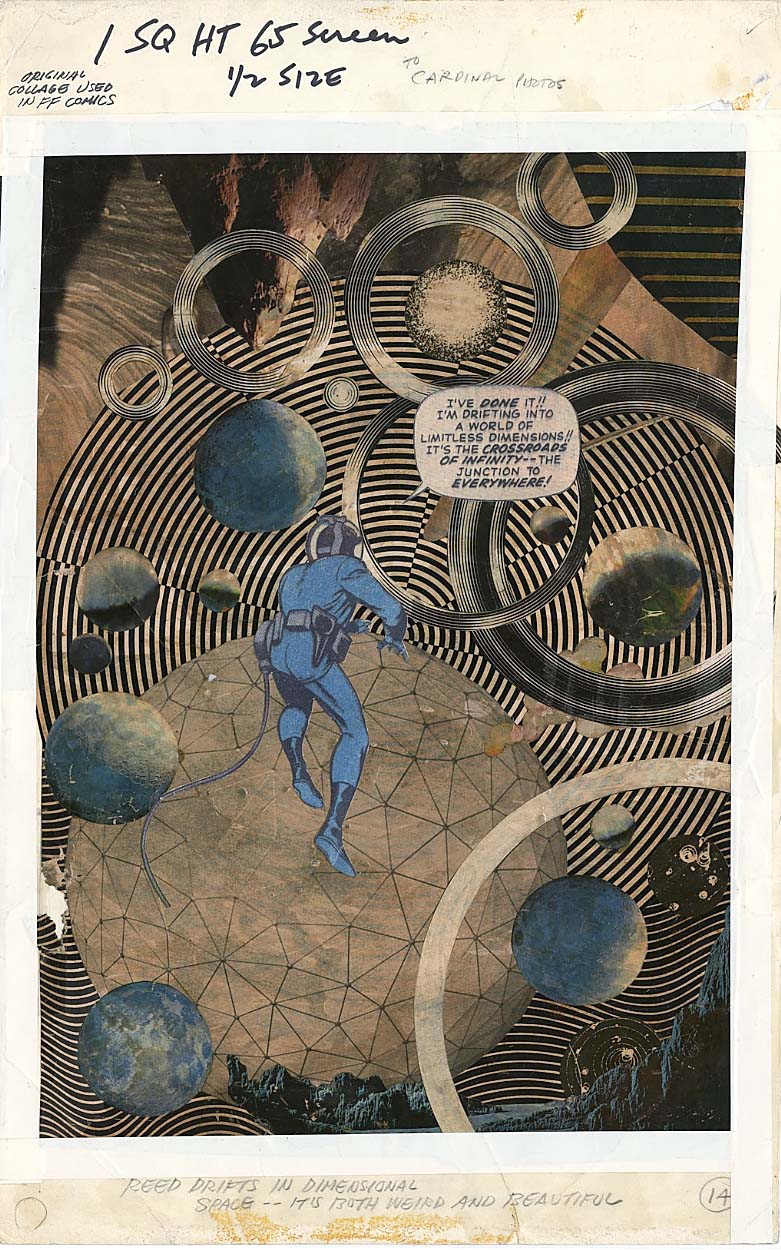

For me, in those years, Kirby’s work seemed blocky, for want of a better word and almost too well-lit. His style didn’t suit the shadows of my moody pre-adolescence. Yet, in “Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity,” with a look past the covers and the published art, at Kirby’s drawings and paintings, his rendering of worlds, as in Fantastic Four #51, his technological fantasies, like “Metron,” his deep dive into abstraction in his later works such as Devil Dinosaur and, in light of what I have learned as a result of the exhibition, about his life, about the antisemitism he faced and a war against fascism that he himself fought in, I find myself reappraising — and praising — his work.

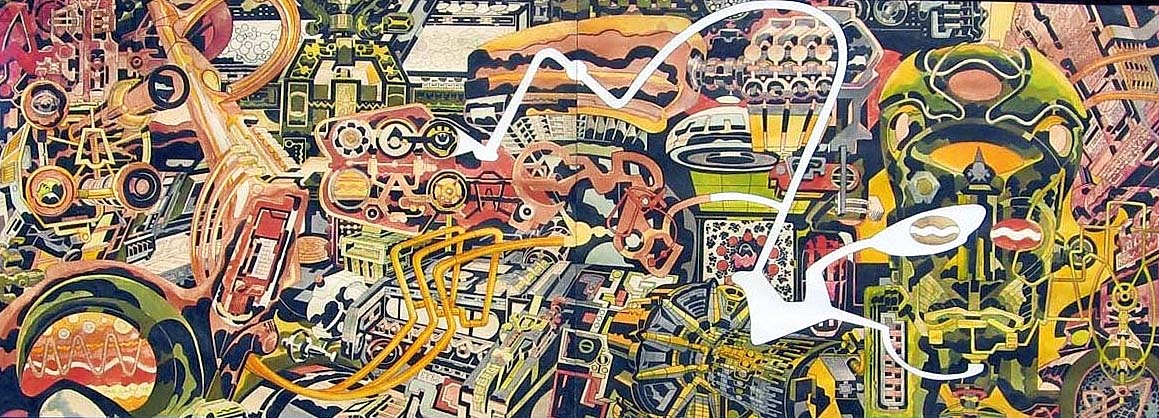

“The Dream Machine” by Jack Kirby, circa 1975, pencils and watercolor by Jack Kirby.

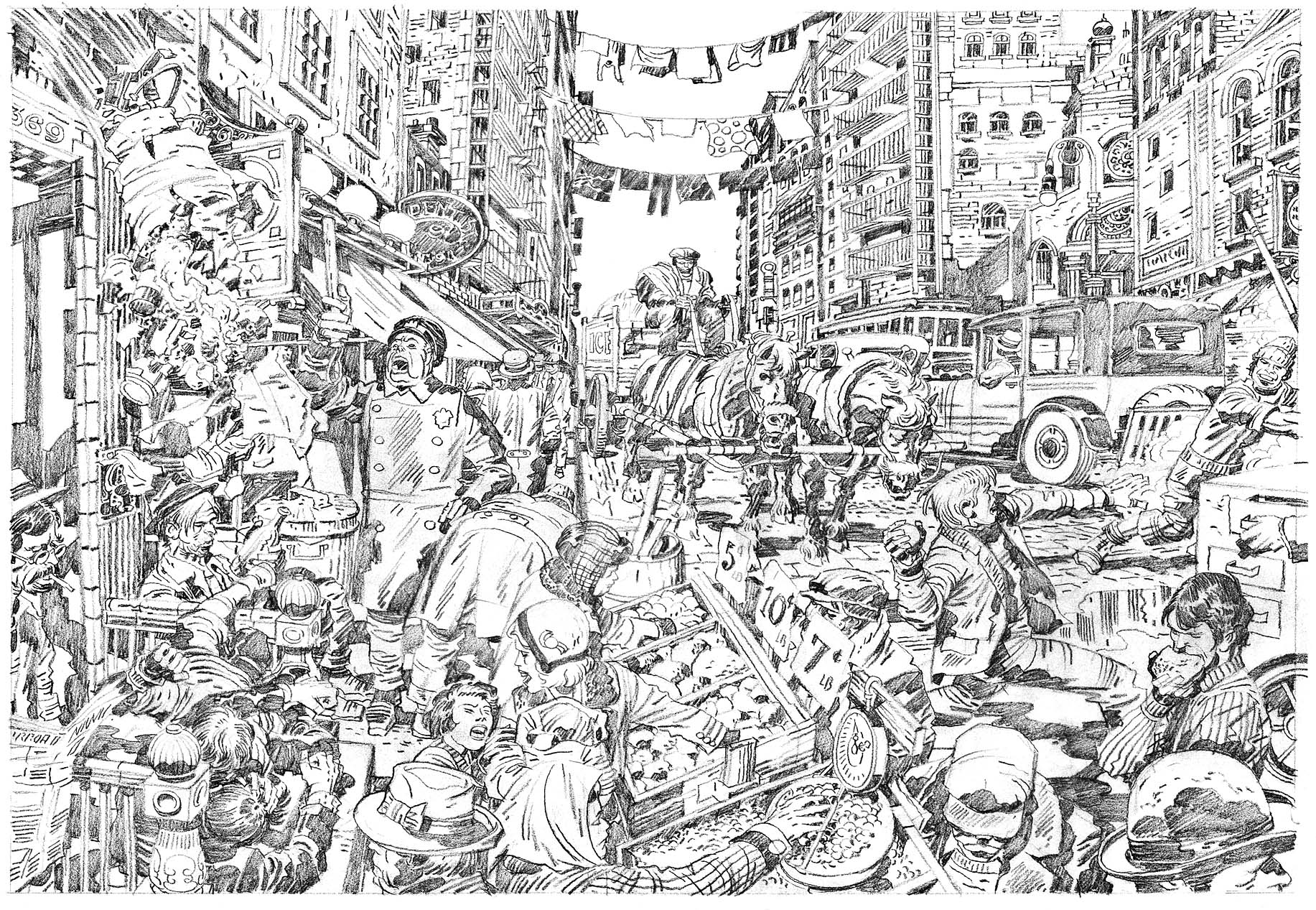

Two works, “Street Code” and “Dream Machine,” do not, at first glance, seem to warrant comparison. “Street Code” is an ode in pencil to Kirby’s own origins on New York City’s Lower East Side. The drawing is edge-to-edge with figures of every race, color, class, age and occupation, interlocked in the cacophony of the city when it was half horse-drawn, half internal combustion and vibrating with humanity, day and night.

“Dream Machine,” on the other hand, excludes humanity. Only accidental suggestions of faces break the interlocking madness of technology. What does all of this do? What is it for? Who — or what — invented it? It’s the ludicrous complexity of a Rube Goldberg contraption gone wild.

Interlocking. See that word up there? All connected. Human. Machine. Makes no difference. In Kirby’s art, we’re always bound together, even when it seems, looks and is depicted as though we are coming apart. That heroes and villains alike share in the deliberate blockiness of his style is an indictment of our inability to see that we are all much closer to one another than our prejudices indicate. It is as if the blocks that make up all of Kirby’s characters are extensions of the atoms we — and everything — are made of. It’s our inability to recognize this that leads to the wrongheaded notion that difference is vertical, a hierarchy of better and worse, worthy and unworthy, a notion the leads to evil and to the need to combat evil.

Page 14 of Fantastic Four #51, by Jack Kirby, 1966, pencils and collage by Jack Kirby, inks by Joe Sinnott. © Marvel.

In the sudden slant of shadows on this last day of August, I am listening to the cicadas and the first zephyrs of fall — zephyrs is a good comic book word. I’m reading my Kirbys. But I’m going to end with Tomb of Dracula #50, a book Kirby did not work on, though he conceived and created the Silver Surfer, who is summoned in Tomb of Dracula #50 to do battle with the greatest vampire in literature. Kirby’s own words in an interview on the Kirby Museum website tell the origin story of Galactus, the destroyer of worlds, and the Silver Surfer, herald of destruction who thwarts his master at every opportunity: “My inspirations were the fact that I had to make sales and come up with characters that were no longer stereotypes. In other words, I couldn’t depend on gangsters, I had to get something new. For some reason I went to the Bible, and I came up with Galactus. And there I was in front of this tremendous figure, who I knew very well because I’ve always felt him. I certainly couldn’t treat him in the same way I could any ordinary mortal. And I remember in my first story, I had to back away from him to resolve that story. The Silver Surfer is, of course, the fallen angel. When Galactus relegated him to Earth, he stayed on Earth, and that was the beginning of his adventures.”

In Marvel’s Dracula, the Silver Surfer, realizing that he is not in charge of his powers, recognizes another fallen angel, one that, as events transpire, may not be past all redemption, nor beyond all hope. The black and white, ink on paper, Manichaean dualities of the Old Testament — and even older faiths — that overlay the pencil-gray ambiguities of the human mind and heart lie at the soul of Jack Kirby’s art.

Jack Kirby is drawing me. Or is it Jacob Kurtzberg? At any rate, I’m a centaur. Bicycle-taur? No. Velotaur. Yes, I’m a velotaur, one with my lime green 10-speed Schwinn, on my way to The Turning Page. I’m wondering where my buddies are, today, and what they might be wondering. My shadow is chasing me.

“Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity,” is on view until March 1 at the Skirball Cultural Center, at 2701 North Sepulveda Boulevard. For information, 310-440-4500 or www.skirball.org.