A master creator of historically resonant American interiors, Thomas Jayne combines deep knowledge of the past with an imaginative approach to the present. For a historic house on Philadelphia’s Main Line, Jayne created a tranquil setting for a museum-caliber collection of postwar art, much of it American.

By Laura Beach

NEW YORK CITY – One thing Thomas Jayne, a master creator of historically resonant American interiors, remembers about St Matthew’s Parish School is its architecture. The decorator, whose Manhattan-based firm Jayne Design Studio recently celebrated its 30th anniversary, attended the Episcopal day school as a boy growing up in Pacific Palisades, Calif., not far from the famous Eames House with its seductive high-low mix of folk and function. Modernist architects Frederick Emmons and A. Quincy Jones contributed to the school’s campus, including the chapel Jayne attended daily. Nearby and in use by the church was a handsome 1920s house by the self-taught architect-builder John Winford Byers.

What Jayne gleaned from this early brush with design, he characteristically synthesized into something new. His good friend Tom Savage, director of external affairs at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, notes that Jayne Design Studio’s tagline, “Decoration – Ancient and Modern” is a riff on Hymns Ancient and Modern, a standard Church of England hymnal. But as Jayne’s clients know, the decorator’s interiors are never one or the other. They are a living continuum, a paean to the past as prologue.

Time, theirs and ours, is ever on Jayne’s mind. It has been 35 years since he began his career as a decorator, his preferred description for what he does, at the society firm Parish-Hadley Associates. “It’s all much less formal now. At Parish-Hadley we had a maid in a black uniform who brought us sandwiches on trays. Today we go around the corner to Pret for lunch.”

The bay window with a view of the Maine coast gives the room a nautical quality. The curved bench provides a cozy place for a small dinner. Photo Jonathan Wallen.

This past year was one for the books. “Let’s just say no one moved out of their house into a small apartment to do a gut renovation. That kind of project isn’t happening right now because it’s too disruptive,” he says. Still, Jayne, often working with Jayne Design Studio senior designer William Cullum, stayed busy with projects on both coasts and locales in between.

“Until we can be together again, Zoom is a help,” admits Jayne, who supervised much of a recent Philadelphia project from afar and is pleased with results. “My client and I have been building things for decades, so we knew what to watch for.” A project in Charleston is unfolding on FaceTime and Instagram. “Even though we haven’t been there since February, we have a pretty good idea of what’s going on.” Another in Miami has been harder.

Jayne is unfazed by the cyclical nature of taste. “People who love antiques seek us out. That doesn’t change,” says the decorator, whose style and approach are documented in his three imaginative books, all published by the Monacelli Press. The Finest Rooms in America (2010) cemented Jayne’s association with a broadminded array of historic interiors, from Monticello to the Menil Collection, a Modernist mecca in Houston. A compilation of his own work, American Decoration (2012) illustrated the breadth of his practice and evolution as a designer. With his ambitious Classical Principles for Modern Design: Lessons from Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman’s The Decoration of Houses (2018), Jayne underscored an approach to design committed to timeless values.

“I wanted the living room at Chandler Farm to be as suitable for the Cadou children as for a cocktail party,” says Jayne, who combined family furniture with study objects and reproductions that had been scattered around the estate. Cadou salvaged the discarded green silk on the wing chairs from a previous project. Photo James Schneck.

As the period-room aesthetic fades from fashion, collectors sometimes wonder how to live with antiques in a way that seems authentically of the moment. There are, of course, tricks of the trade to freshen a room, but the vitality of Jayne’s designs goes more viscerally to his absorption of the values exemplified by two spiritual mentors, collector Henry Francis du Pont (1880-1969) and designer Albert Hadley (1920-2012). As a graduate student at Winterthur, Jayne internalized du Pont’s gift for color, decoration and room arrangement, learning, as Savage has put it, “everything we at Winterthur weren’t teaching.” Jayne writes that he respected Hadley, a rigorous editor who pared his interiors to the essence, “for his fantastic eye for design, his talent for combining unexpected colors and elements, his appreciation for history as well as for the new, and his unerring sense of decorum.”

Jayne’s talent for tweaking tradition comes from his thorough understanding of precedent. As Savage, who met Jayne 37 years ago while participating in the Victorian Society’s London Summer School, says, “You can’t break the rules if you haven’t studied them, and Tom knows how to break the rules. His color sense can be extremely fresh, but it’s based on careful attention to period sources.”

One of Jayne’s first published commissions was for Savage, then working for Historic Charleston Foundation and living in an outbuilding on the grounds of the 1772 William Gibbes House on Charleston’s South Battery. “We were poor but loved working together. Thomas sent me the late Michael Lane, the decorative painter, who did some wonderful Neo Palladian decorative paint work and taught me how to finish it. An article in House Beautiful called the project a parlor game played by two people deeply rooted in history,” Savage says.

A modern Parsons-style dining table amid a collection of antique furniture creates a contemporary design contrast. Photo Pieter Estersohn.

Few American designers have worked on a property as magnificent as Crichel House, a Dorset country estate begun in the Tudor era and since 2013 owned by Richard L. Chilton Jr, a Metropolitan Museum of Art trustee, and his wife, Maureen K. Chilton, chair emerita of the New York Botanical Garden. At their direction, Jayne Design Studio – working with architectural historian John Martin Robinson, historic paint consultant Patrick Baty, Peregrine Bryant Architects and restoration craftsmen Hesp Jones & Co Ltd. – restored and furnished principal state rooms designed by English architect James Wyatt (1746-1813) to their original Neoclassical splendor, a process documented in Country Life in 2017. The work, completed in 2015, won awards from The Georgian Group and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art.

Jayne’s previous engagements with private social clubs in New York – he worked for the Colony, Union and Knickerbocker Clubs – prepared him. “I’d certainly decorated a lot of Eighteenth Century rooms and the clubs had scale, so I had some experience,” he recalls. In addition to scouting antique furniture and a chandelier for Crichel’s dining room, Jayne Design Studio commissioned chairs from Harrison Higgins in Richmond, Va. A custom carpet is in the works now. For Crichel’s drawing room, Jayne returned Regency chairs original to the house to the scheme as part of a new furnishing plan. Silk walls were rewoven by Humphries.

Before a 2018 appearance at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn., Jayne and Cullum revisited the Mark Twain House and Museum. Inspired by details such as a pink and silver drawing room with stenciled walls by Associated Artists, Jayne Design Studio is incorporating similar elements into a house of roughly the same age in Oyster Bay on Long Island, N.Y.

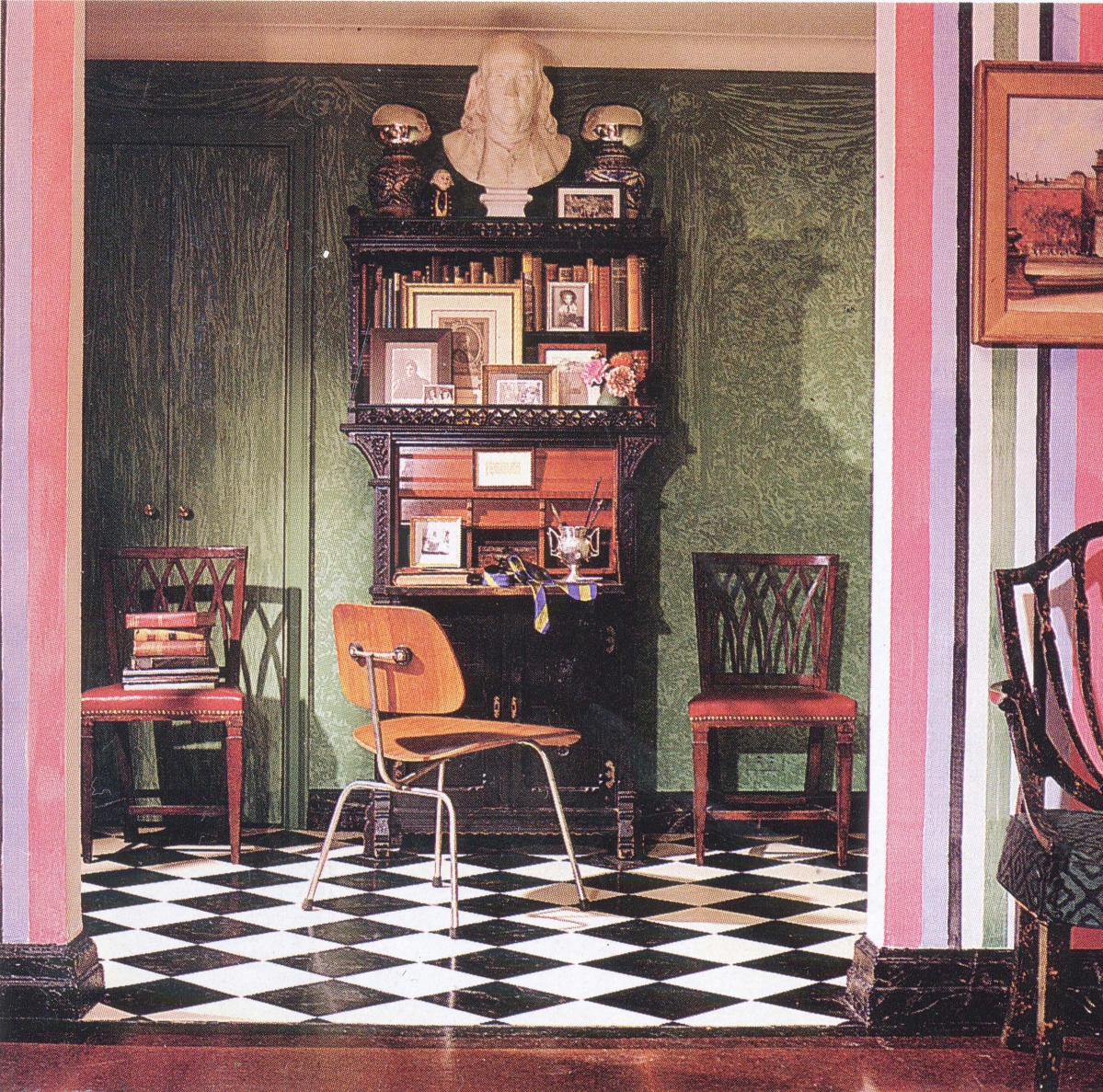

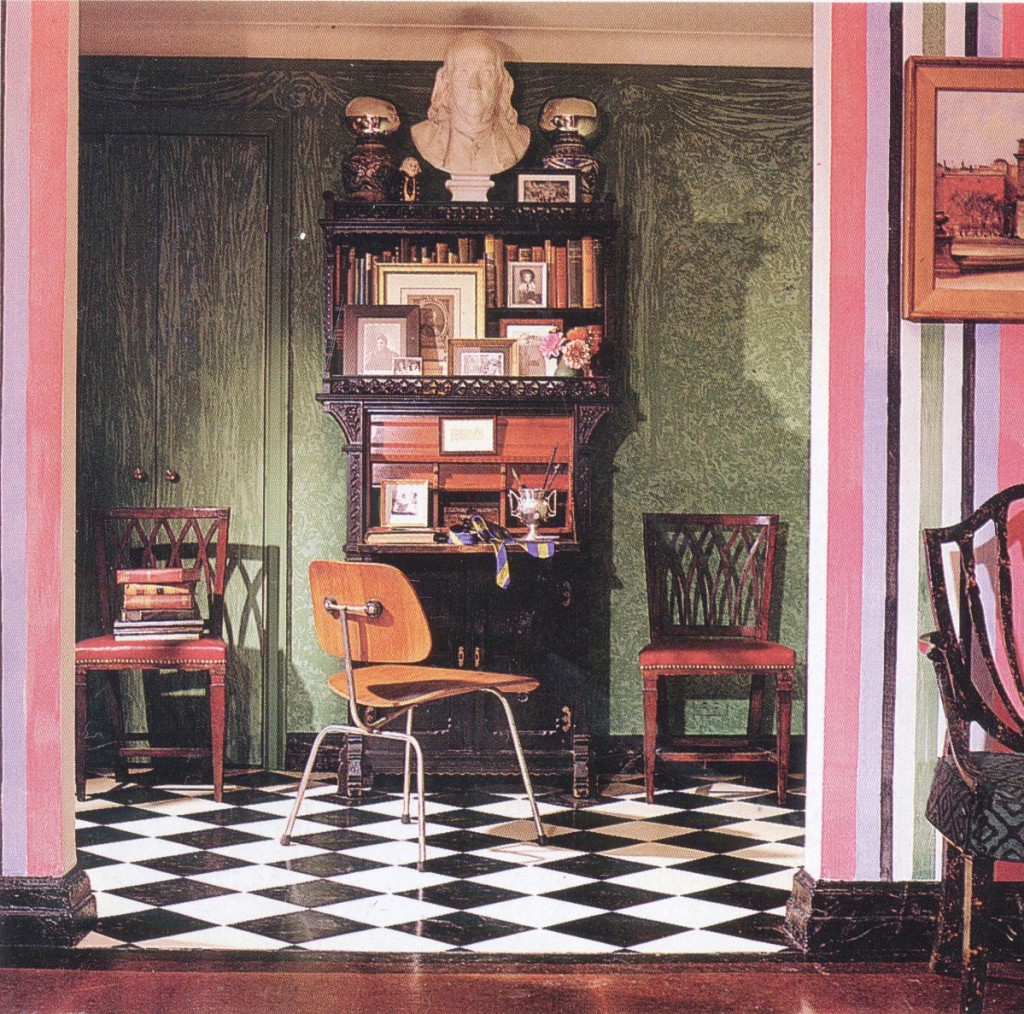

Jayne’s first apartment on Washington Square. The stripes and other decorative paint updated the prewar architecture of the rooms. Photo Andrew Garn.

Jayne maintains steady contact with museum and institutional colleagues, who often seek informal advice on historic fabrics and traditional workrooms. They sometimes ask him to redecorate rooms and install collections. The projects have ranged from the President’s House at Yale University to working with former Shelburne Museum president and chief executive officer Hope Alswang on the refurbishment of Electra Havemeyer Webb’s Brick House and creating a backdrop for the 2014 exhibition “Making It in America” at the Rhode Island School of Design’s Museum of Art.

Last spring, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library unveiled its most recent collaboration with Jayne, his pro-bono redecoration of Chandler Farm, since 1958 the traditional residence of Winterthur’s directors and the current home of director and chief executive officer Carol B. Cadou, who assumed her post in May 2018. Located on the estate’s rolling grounds, the brick farmhouse, the core of which dates to around 1805, had in recent years been leased by Winterthur to tenants.

“Chandler Farm was an extraordinary building with terrific bones and a rich history, but the amount of work it needed just to bring it up to standard was daunting,” says Cadou. “I asked Thomas to work with me to envision the first floor as a public space for entertaining as well as for telling the Winterthur story. I wanted a second-floor guest room for Winterthur’s special guests. At the same time, we needed a comfortable family home for our children.”

Jayne enlivened Chandler Farm’s dining room with a bright, historic print from Adelphi Paper Hangings and covered reproduction dining chairs with printed linen in contrasting shades of cobalt and raspberry. Photo James Schneck.

“Functionality was important,” acknowledges Jayne, who has known Cadou since they met at an event for Winterthur alumni in 1995. For the new design, Cadou and Jayne gathered Cadou family pieces, study objects and reproductions, some from Kindel Furniture’s Winterthur Collection and scattered about the estate, placing the works in settings made vibrant through the creative use of paints, textiles, wallpaper and scatter rugs.

Jayne painted the living room walls at Chandler Farm a pale pink, lined white bookcases with wallpaper he created by digitally scanning an archival blue and white resist fabric, and covered wing chairs with mint-green silk damask salvaged by Cadou from George Washington’s Mount Vernon, where she worked for more than two decades. “These discarded bolts of fabric traveled with us for 18 years, something my husband teased me about,” Winterthur’s director says.

Jayne papered dining room walls with an Eighteenth Century print in bold florals from Adelphi and covered dining chairs with printed linen, contrasting their bright blue fronts and seats with raspberry-colored backs. The pièce de résistance is Chandler Farm’s stair hall. There, with help from his husband, food stylist Richmond Ellis – whose long proximity to the art and design fields makes him the decorator’s most trusted critic – Jayne and Cadou invoked an Eighteenth Century print room in the manner of Castletown House in Ireland, attaching assorted prints and photographs of Winterthur people and places through the decades directly to the wall, then surrounding the images with trompe l’oeil frames derived from historical prototypes in Winterthur’s archives and from the collection of Colonial Williamsburg’s deputy chief curator, Margaret B. Pritchard.

The Eighteenth Century paint scheme of this room at Crichel House in Dorset, England was restored with Jayne Design Studio’s advice. Photo Paul Highnam, courtesy Country Life.

“From the vantage point of the staircase, I wanted to be able to tell guests the entire story of Winterthur before they moved on to their cocktails or dinner,” Cadou says of the sequence of images featuring museum founder Henry Francis du Pont, first director Charles F. Montgomery and even Jayne and Cadou themselves as Winterthur students. Tapped to serve as design co-chair of the 2021 Winter Show, Jayne will discuss the Chandler Farm project with Cadou as part of the fair’s virtual “Conversation with Curators” lecture series. The Winter Show has also asked him to curate a “virtual viewing room” with his favorite pieces from the fair and provide commentary on his choices.

Jayne’s own residences are laboratories for experimentation. He explains, “I learned this from Albert Hadley. Decorating your own place is a way to think outside the box and live with new ideas. That said, a well-decorated room should last for years and mature with time.”

For the 1,800-square-foot Soho loft he shares with Ellis, Jayne harnessed the power of personal narrative to transform what was essentially “a big white box” into a learned, comfortable, mildly bohemian connoisseur’s retreat housing their assorted collections, including Ellis’s 5,000-volume library of rare and vintage cookbooks. For the couple’s flat in an 1836 Creole townhouse in New Orleans’ French Quarter, Jayne wanted a scenic wallpaper. Not satisfied with the “usual suspects,” which he considered too grand, he asked De Gournay to create new paper based on illustrations from The Story of The Mississippi, a 1941 children’s book given to Jayne by his grandparents decades ago. The lively mural adds Jayne’s indelible imprint to the setting’s colorful past.

Jayne’s newest project for himself is a tiny house – in zoning parlance an accessory dwelling unit – that he is erecting on the Pacific Palisades property where he grew up. “It’s contemporary in style, boxy with a skylight. Because of size limitations, a pediment was out of the question,” says the designer, who is collaborating with architect Russell Thomsen on the structure meant as a celebration of Jayne’s oldest friend and Russell’s late partner. “Russell and I see our friend in each other, which makes our collaboration especially sweet.”

The Soho loft Jayne shares with his husband, Richmond Ellis, a food stylist and historian, is a laboratory for design ideas. Yellow mirrored doors open into a contemporary version of a connoisseur’s cabinet room filled with specimens and objets d’art. Photo Don Freeman.

Attuned to historical continuum, Jayne, unsurprisingly, has thought about his own place in it. With client permission, he is donating papers relevant to specific projects to appropriate institutions. He contemplates writing more books. One, “so people know what to ask for,” might discuss traditional details. The other, he says impishly, would be called The Material Culture of Myself and be a discreet form of memoir.

Modestly, he says his foremost contribution to the field of American interiors is perpetuating tradition. “We’re like seed savers. We keep things alive that otherwise might be extinct. At Jayne Design Studio we know all aspects of traditional design – how to do traditional upholstery, how to make trims and gimps, how to hang curtains. It sounds grandiose, but we represent the apostolic succession of old-fashioned decorators reaching back directly through Albert Hadley, Eleanor Brown and Sister Parish to Elsie de Wolfe.”

Jayne’s long collaboration with antiques collectors and curators inoculates him against such regrettable fads as ubiquitous gray and indiscriminately open-concept floorplans. But as a fan of dining rooms and other quarters dedicated to inspired hospitality, Jayne is prepared to make one prediction: “After being quarantined together, people will again appreciate the idea of separate spaces.”

Jayne Design Studio is at 118 East 28th Street. For more information, 212-838-9080 or www.jaynedesignstudio.com. For more on the Winter Show, go to www.thewintershow.org.