The John Michael Kohler Arts Center

Untitled grotto by Madeline Buol, circa 1948; concrete, stones (including quartz, granite and metamorphic and igneous rocks from glacial outwash), marbles, shells, glass, ceramic, metal and plastic. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Robert and Lisa Klauer and Kohler Foundation Inc. Photo courtesy of John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

By James D. Balestrieri

SHEBOYGAN, WIS. — The night Sinatra died, my wife and I were living in a rapidly gentrifying Italian neighborhood in Brownstone Brooklyn (N.Y.), twilight time for red sauce ristorantes that didn’t serve pies — pizza to you — on Sundays; “Sundays are for family meals.” In the little front yards of the brownstones, off to one side of the steps up from the parlor level to the first floor, geraniums grew in widow-tended pots. In these same front yards, little grottos of brick, stone and shells stood, holding likenesses of Mary and Jesus. Candles lit them on saints’ days and holidays.

The night Sinatra died — May 14, 1998 — images of Ol’ Blue Eyes, cut from the covers of the New York Post and every other publication, displaced the mother and son of God and took up temporary residence in the grottoes of Brownstone Brooklyn. Squat tea lights and tall prayer candles illuminated them, flickering along as if keeping time to the sounds of Sinatra that came from the windows of Brownstone Brooklyn. The old stations and the old Sinatra DJs, Sid Mark and Jonathan Schwartz among them, spun the Sinatra catalog for 24 hours, through the wee small hours of the morning. My wife and I sat on the stoop of our brownstone, shaking martinis — I could drink martinis then — and letting the smooth liturgy drift over us on the late spring, early summer wind.

Those grottoes got to me. Then and now, they got to me as spontaneous expressions of secular faith, a collective “Grazie” for Frank Sinatra’s music. They were shrines of joy that overmastered grief. Like the Sinatra grottoes in Brooklyn, the incredibly intricate works in “A Beautiful Experience: The Midwest Grotto Tradition,” now on view at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, sprang up in a specific area, in Wisconsin and northern Iowa, and flourished over a specific span of time, circa 1912 to 1960. The makers of the Midwest grottoes were self-taught — that is, they did not train to be nor consider themselves artists — and were driven by a shared impulse, one that, like the phenomenon of the Sinatra wake, embraces sociology, anthropology and spirituality.

Installation view of “A Beautiful Experience: The Midwest Grotto Tradition.” Photo courtesy of John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

The exhibition literature states: “Materially, Midwestern grottoes often reflect local industries, decorative trends and an area’s geological makeup. Grotto architecture mainly comprises concrete embellished with objects including shells, marbles, colored glass, toys, figurines, fossils and geodes. This accumulation, as well as the objects incorporated, creates a documentation of the maker’s life, faith and home.” What this quote doesn’t say is that each grotto is made up of objects running into the millions, each placed within a larger design, unique unto itself. All of the Midwest grottoes, however, share an aesthetic that came to America with German immigrants. With one crucial distinction: German grottoes are traditionally created in naturally formed caves. The cave is the canvas in which the aesthetic elements — whether they are religious, mythical or simply whimsical — are placed. In Wisconsin and northern Iowa, though they do have their share of suitable caves, the artists of the grottoes created the spaces themselves. Some resemble chapels carved into rock; some are freestanding structures in the form of chapels. Others are rock gardens with fountains and walkways that lead to a shrine. Still others are fashioned to resemble Old World catacombs, complete with figures from antiquity, or are folk art follies filled with figures and fanciful turrets.

Scholars, seeking the origins of the Midwest grottoes, saw them as attempts by German immigrants to signal that even though they were foreign, and even though their Catholic rite was spoken and sung in German, they were and wanted to be seen as American. “Fitting in” makes sense in light of American attitudes towards Germans during the two World Wars and accounts, perhaps, for the patriotic elements in some of the grottoes, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. In fact, there was little attempt to publicize the grottoes and, when you step back and take them in — and then move close and see how they are made and what they are made of — they are more than a little off-putting. Why not just build chapels in recognizable forms? Why are so many of these grottoes memorials to individuals, or simply artist-built environments meant to let the imaginations of visitors soar? While we can know something of the artists’ intentions, we can’t quite know the depth of their passion and devotion. The Midwest grottoes, despite being for the public, remain, in large measure, private and personal, reserving ultimate meaning for their makers.

At left, “St Peter’s Basilica” by Madeline Buol, circa 1948, concrete, stones (including quartz, granite and metamorphic and igneous rocks from glacial outwash), marbles, shells, glass, ceramic, metal and plastic. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Robert and Lisa Klauer and Kohler Foundation Inc.

The word grotto itself comes from the Italian word grotta, or crypt, and refers back to the idea of a cave of wonder, and of transformation. Grotto gets us to another word — grotesque — whose connotations split between ugly, malformed, monstrous and ridiculous, as well as astonishing and fantastic. What unites these definitions is still another mysterious concept, one we rarely explore in the arts: excess. And the words that define these artists — inasmuch as they can be defined — are self-taught, outsider and folk.

Beginning in the 1880s, and still unfinished, the Midwest grottoes have a “wonder of the world” analog — the Sagrada Família — Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí’s (1852–1926) soaring personal interpretation of Gothic cathedral architecture. In this comparison, perhaps, might we find some new old questions that bear on the true origins of the Midwest grottoes? For example: What did humanity relinquish when the assembly line became a symbol of modern life? And: How did the first industrial-scale wars confirm this? Is the impulse that led to the Midwest grottoes similar to that which led to the dreamscapes of Modernist art? Of the Arts and Crafts movement? Of a new interest in the handmade and in artistic expressions of people’s inner lives?

Taken this way, the Midwest grottoes, as well as other personal passion projects, like The House on the Rock, a monument to excess if ever there was one — and the perfect foil for the austerity of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, which is just down the road — are, despite the positive messages and feelings they want to convey, very much like the monsters in the fictions of H.P. Lovecraft and others of this same period: sprawling, grotesque and deliberately impossible for the human brain to apprehend all at once, if ever.

Untitled grotto by Madeline Buol, circa 1945-47, concrete, stones (including quartz, granite, basaltic volcanic scoria, Baraboo quartzite and metamorphic and igneous rocks from glacial outwash), marbles, shells, glass, ceramic, metal and plastic; 68 by 32 by 38 inches. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Robert and Lisa Klauer and Kohler Foundation Inc. Photo courtesy of John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

But isn’t divinity supposed to be impossible to take in, to apprehend? That the Midwest grotto tradition begins with parish priests such as Father Matthias Wernerus who, along with his parishioners, created the Dickeyville, Wis., Grotto between 1924 and 1930, suggests a desire to situate his church and flock in that idea that the glory of God is infinite and that it requires something from all of us to enact it here on earth. Perhaps the same can be said of the work of the imagination, the work of art.

Consider Madeline Buol’s Buol Grotto and Sculptures, created between 1946-60. Buol, one of the “few known women grotto builders… utilized include figurines and stones gathered during her travels…[and] had a special affinity for shells of all shapes and sizes.” All the elements of a Catholic altar shrine are there, with a nod to patriotism in the form of an American flag. Crosses and attention to symmetry in the small grottoes to either side of the central grotto containing the statue of Mary are there and are to be expected, but the tall loops that flank the central construction are rosaries that stand in defiance of gravity, dwarfing the grottoes themselves. From a distance, envision the whole as a temple in a celestial city, flanked by these two tremendous non-Euclidian structures straight out of science fiction.

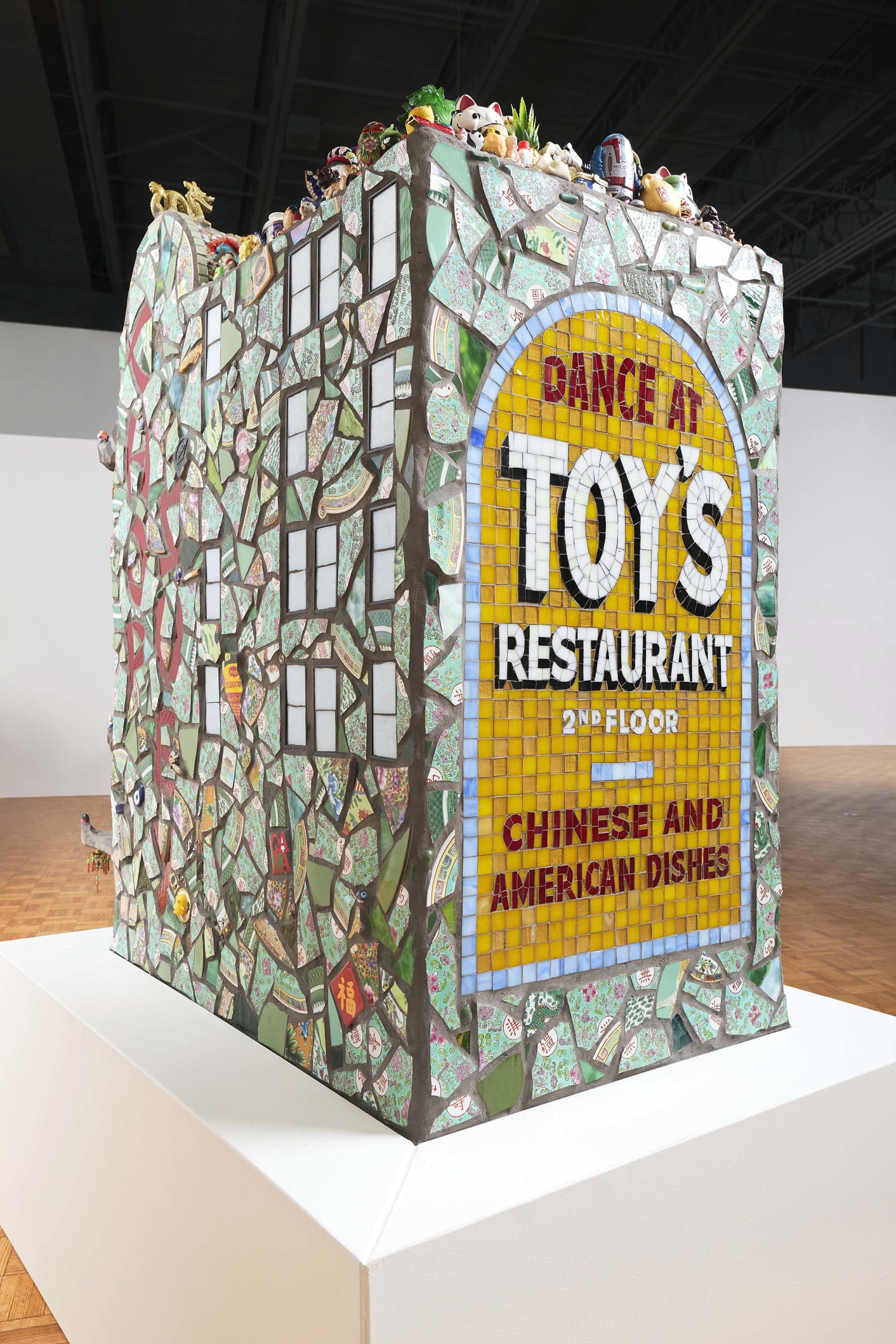

The exhibition “also includes new work by Stephanie Shih and E. Saffronia Downing, each responding to the grotto tradition.” Downing finds something in the materials of the grottoes, in the broken bits of brick and glass that become mosaics, and especially in the concrete — one of the armatures of the Industrial Revolution, and the stuff of the rise of modern cities — while Shih makes the grotto into a medium of historical exploration. In “Toy’s Restaurant,” for example, Shih revisits an early Chinese establishment that became a fixture in Milwaukee, transforming the miniature house motif of Midwest grotto artist Jacob Baker (circa 1880-1939) into a metaphor for the successes and setbacks that Chinese immigrants experienced. Broken, mended with concrete and fashioned into walls, the pieces of colorful porcelain that Shih employs to create “Toy’s Restaurant” seem to symbolize the ways in which America often breaks immigrants, who then have to remake themselves. Adding to this, the Chinese “toys” and figurines atop the restaurant are colorful, whimsical and — perhaps intentionally — alienating images of a courageous culture that dares to retain its identity.

“Toy Building” by Stephanie H. Shih (1915-1939), 2025, Chinese export porcelain, crowdsourced and found objects, archaeological ceramic fragments from a Chinese fishing village on Monterey Bay (circa 1850–1906), stained glass, ceramic, polished stones, glass rods, resin, enamel and grout on ferrocement, steel and polystyrene. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, courtesy of the artist. Photo courtesy of John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

Art, in order to remain art, insists that we seek its ever-receding edge, that we ply the darknesses and brave the turbulence in order to wrest new ideas and forms from it. This may be equally true of faith. Turn once again to grotto become grotesque, and to grotesque as monstrous. Monster begins life in the notion of warning, finding relationships with words like admonition and premonition. Perhaps, while the Midwest grottoes are calls to worship, their role as calls to wonder, to dream and to imagine, are equally important in an age where we just might hand art — and all products of imagination — over to the machine. The revolution we are going through, however, is far cleverer and more insidious than the factory. It’s going to take as many Sinatras in shrines, and other excessive expressions of passion, as we can muster to counter it.

“A Beautiful Experience: The Midwest Grotto Tradition” is on view at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, at 608 New York Avenue, until May 10. For information, 920-458-6144 or www.jmkac.org.