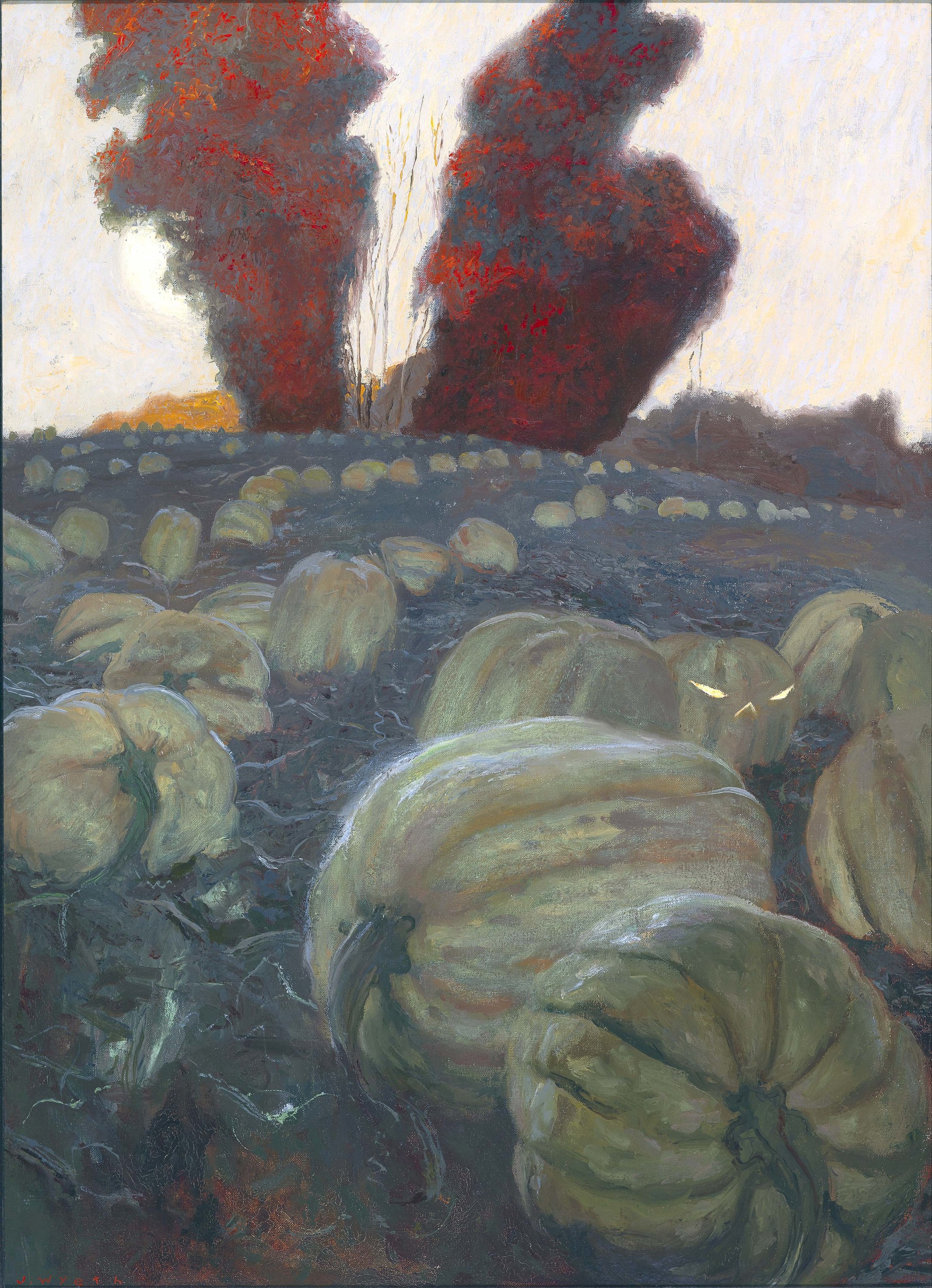

“Spindrift,” 2010, oil on canvas, 40 by 46 inches. The Phyllis and Jamie Wyeth Collection. ©Jamie Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

By Kristin Nord; All Paintings by Jamie Wyeth

ROCKLAND, MAINE — “Jamie Wyeth, Unsettled” has just opened at The Farnsworth Museum of Art and it is a wash of vibrant color, and startling encounters with flora, fauna, land and sea. This show is a spirited immersion into the encounters and dreams of this contemporary Wyeth (b 1946), who continues to thumb his nose at trends in producing art according to his own inner compass.

Wyeth is part of a family legacy that extends from his larger-than-life grandfather, the legendary illustrator Newell Convers (N.C.) Wyeth (1882-1945), whose depictions of pirates, knights and swashbucklers shaped the dreams of many generations. An obsessive devotion to art coursed from N.C. through his progeny: Andrew, daughters, Henriette and Carolyn, and on to Jamie, nearly all of whom have found creative sustenance in the scenes and rhythms of life in and around Chadds Ford, Penn., and Midcoast Maine. Jamie grew up exposed not only to his father’s devotion to art and its daily practice, but to the props in his grandfather’s studio that inspired his illustrations for Kidnapped, Treasure Island and The Yearling. To this day, dressed often in plus-fours like his aunt and his grandfather, Jamie looks a bit like his grandfather’s doppelganger.

He gained notice early with his often-unnerving celebrity portraits and we see where his unflinching depiction of the legendary Dr Helen Taussig got him into hot water. “They wanted a representation of women in medicine as sweet nurturing individuals,” said a clearly amused Amanda C. Burdan, PhD, senior curator at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, where the exhibition launched. “Perhaps they should have known that Wyeth often sees the depth and conflict in object and people — if they had they would have chosen some other painter to do the work.” A later portrait of his good friend Andy Warhol was similarly honest, prompting Warhol to urge the portraitist to tone down the “pimple pink.” Lincoln Kirnstein, a family friend, had seen the makings of a young John Singer Sargent in Wyeth, but, by 1968, the artist was already shifting his laser focus from humans to animals. Whether a ram looking out to sea, or a pig lulled into senescence by the recording of Mozart, Wyeth was mixing his virtuosic drawing and painting skills with acid colors. Unlike his father’s delicate and often deeply poetic meditations, Jaime is more likely to play cinematically with tableaus that hint strongly at the potential for danger and violence.

“Bones of a Whale,” 2006, oil on canvas, 60-1/8 by 72-1/8 inches. Collection of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Mo. Bebe and Crosby Kemper Collection, Gift of the Enid and Crosby Kemper Foundation, 2006.19.01. ©Jamie Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Looking at the family history, one has to wonder if Jamie’s worldview is truly dark and unforgiving, or if, like a master magician, he is drawn to stagecraft, drama and spectacle. Some of his paintings, Burdan, who curated the exhibition, readily admits, “have the capacity to make the hair stand up on the back of one’s neck.” But, one also has to remember that Wyeth and the many generations of his family loved drama and were famous for a legendary faux-funeral procession that scared the dickens out of onlookers at a Thomaston, Maine, Fourth of July parade.

“Across the decades of his career, Jamie Wyeth has honed his attention onto these unnerving events, zeroed in on uncanny experiences and become a master of the unsettled by marshaling a wide range of disconcerting elements — subjects, compositional approaches and techniques — within his works. Developing a skillful, cinematic shorthand, Wyeth has the power to evoke anxiety in nearly every viewer,” Burdan said.

Take “Bean Boots” (1985), in which a falconer dressed in an oilskin coat and boots peers out from a hat that shades much of his face. As we absorb this scene, we encounter not only the caged raptor but a wall studded with the hunter’s trophies. These are not the run-of-the-mill antlers one might encounter over a fireplace, but skulls with gaping eye sockets and snarling grins.

“Bean Boots,” 1985, oil on panel, 37 by 50¼ inches. Collection of the Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine. Gift of the Cawley Family, 2001.29.1. ©2024 Jamie Wyeth/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Or, “Carney Gull” (2009), a frankly terrifying portrait of a creature poised to attack its prey. “If I were to paint this image in music,” the Scots composer Jennifer Margaret Barker wrote in the catalog that accompanies this show, “I would be obligated to score it for symphony orchestra. Wyeth may have painted a solo gull, but the force of the painting necessitates an 80-member musical ensemble.”

“The rich, vibrant hues of the somewhat abstract background stand in startling contrast with the neutrals of the realistically portrayed gull, swirling across the canvas with an intense ‘Dante’s Inferno’ of yellows and oranges to blacks and grays. One envisions a foreboding darkness within striking distance were the yellows and oranges to be peeled away. In every aspect, it is an unsettling scene, yet one so utterly compelling, too.”

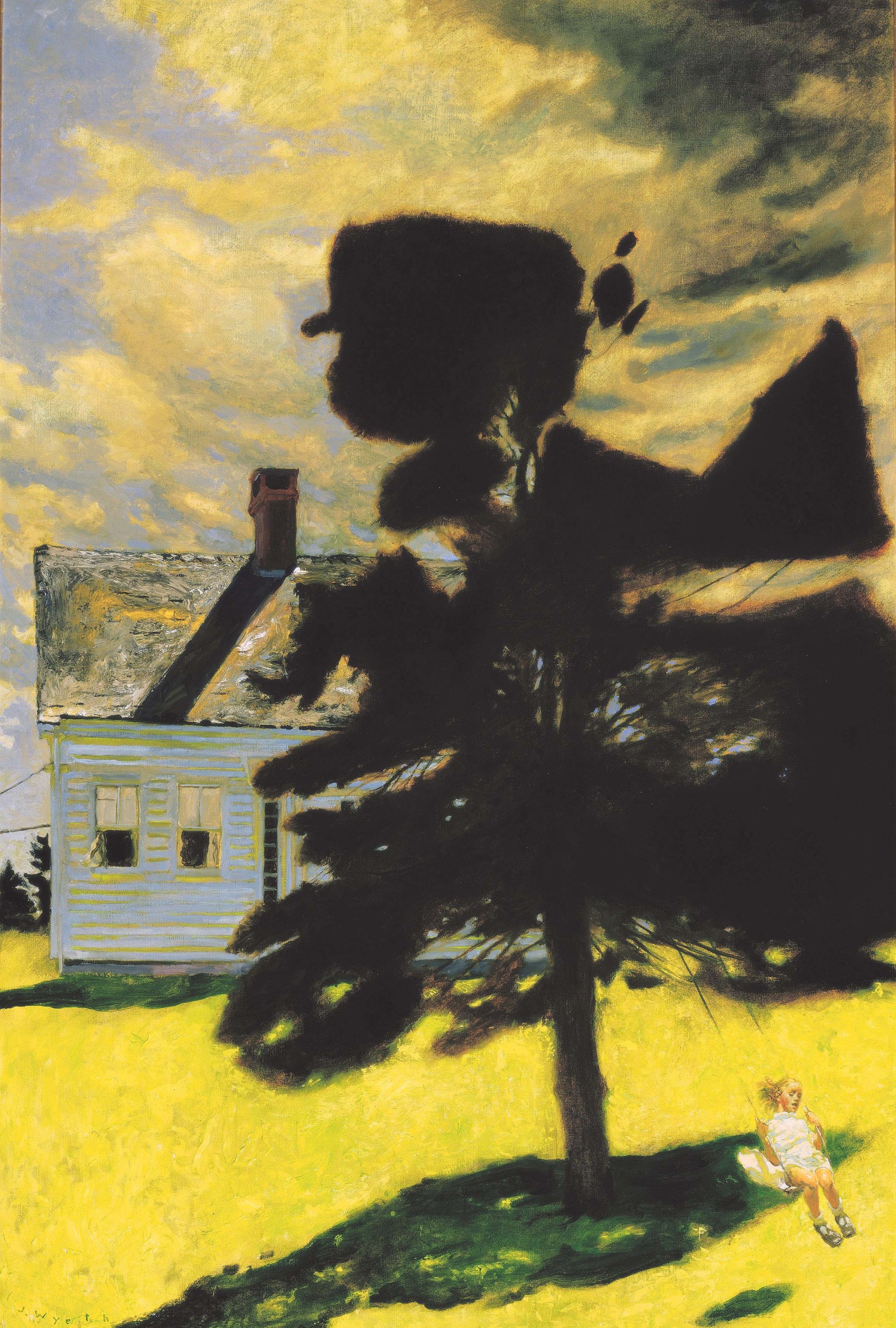

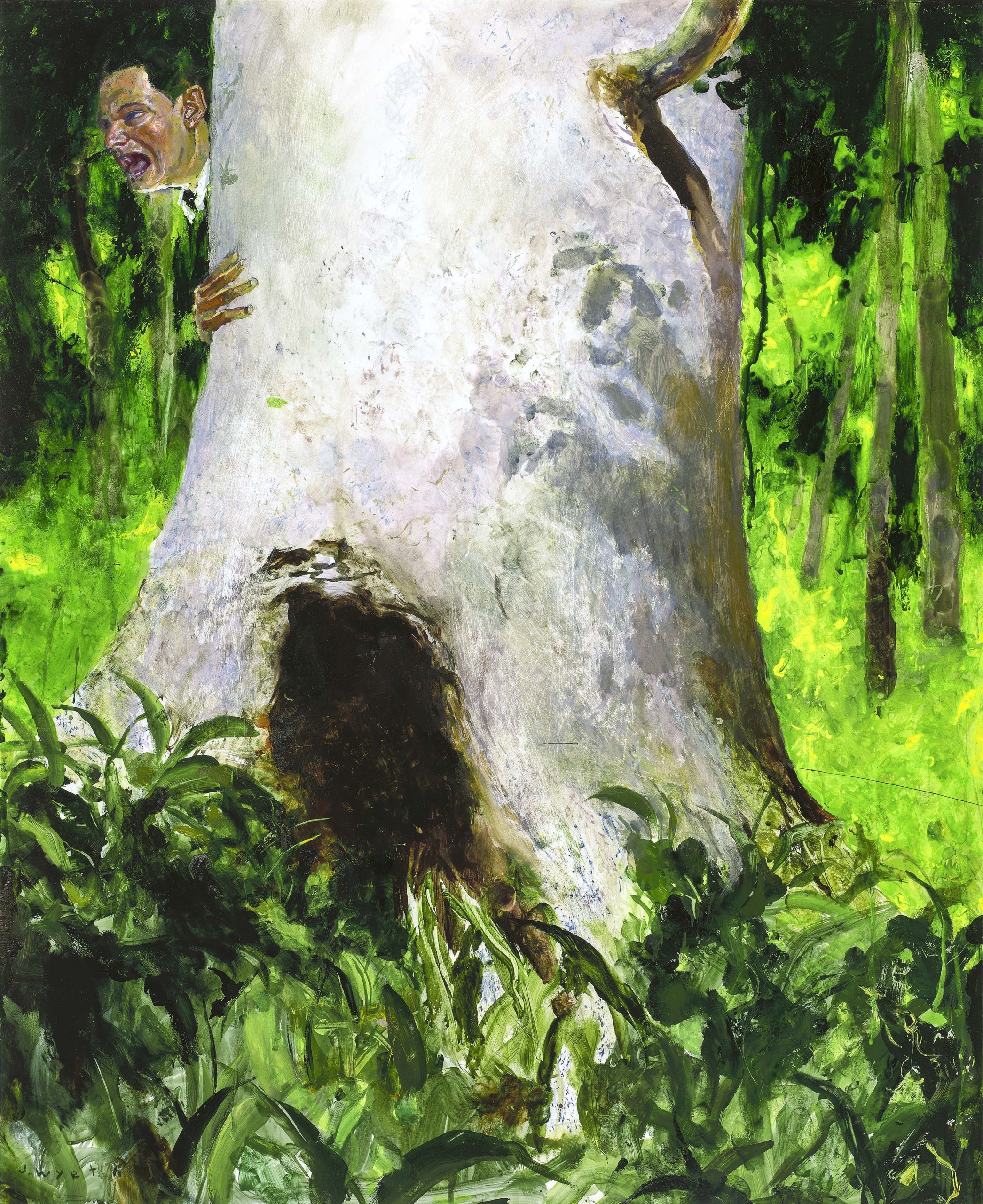

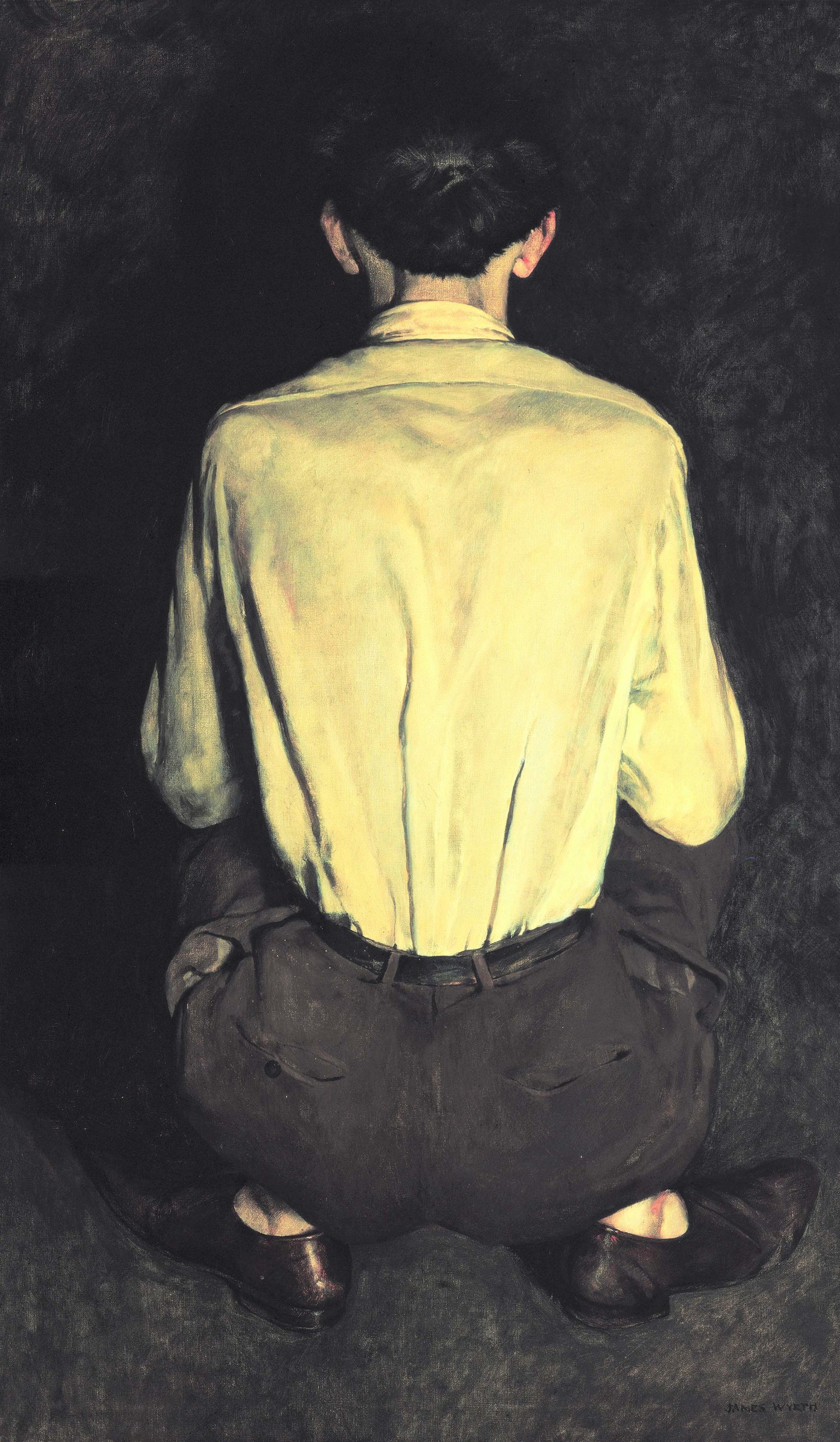

Burdan notes that Wyeth creates tension with the use of two compositional techniques: Ruckenfigur — a backward-turned figure, which in his use, engages the viewer and “seems more of a provocation to come closer ‘if you dare’ — and its polar opposite, in which a confrontational figure comes at the viewer head-on.

Wyeth’s houses feel as unsettled as his animals; even the still life, “Buzz Saw” (1969) leaves us with the sense that an inert object can become a rusty metal industrial carnivore. Consider those blades as menacing teeth!

“Buzz Saw,” 1969, oil on canvas, 30 by 30 inches. Collection of Sherry Delk Kerstetter. ©Jamie Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

“Perhaps not surprisingly, Wyeth’s eerie imagined creations are countered in the real world with the oddities of everyday life. He surrounded himself with unusual collections, many of which consist of precisely the types of objects that the average person might generally find strange. There are things in the world that are scary, even terrifying. Then some things are not quite frightening or upsetting — they are the prelude to fear, the unexplained feeling that something is not right,” Burdan observes.

“Snow Owl, Fourteenth in a Suite of Untoward Occurrences on Monhegan Island” (2020) might simply be a gorgeous example of animalia; that is, until one notices the swirl of birds circling overhead.

In “Portrait of Lady, Study #1” (1968), Wyeth draws us to the sheep’s eyes, which are anatomically correct but are also illustrating in Darwinian terms the animal’s need for utmost vigilance. Ditto with “Sheep Eyes” (1968), which feels like an abstract vision of terror.

One has to wonder if this Wyeth was an unabashed fan of Edward Gorey when we encounter his collection of Victorian era automatons and his own tableaux vivants, in particular the diorama he constructed for his own pleasure that enacts a bloody scene in a butcher’s shop. Automatons, robots, puppets, dolls, taxidermy, prosthetics… anything oddly real or in imitation of life has remarkably uncanny potential. “Bob et son Cochon Savant” is perhaps the creepiest of all in this exhibition. Made around 1880 by Gustave Vichy and his wife, Maria Teresa Berger, this large automaton centers on a clown with a taxidermy pig who is performing stunts in his lap from a miniature ladder. The pig looks alarmingly real, twisting and turning to four songs while the clown claps to the music.

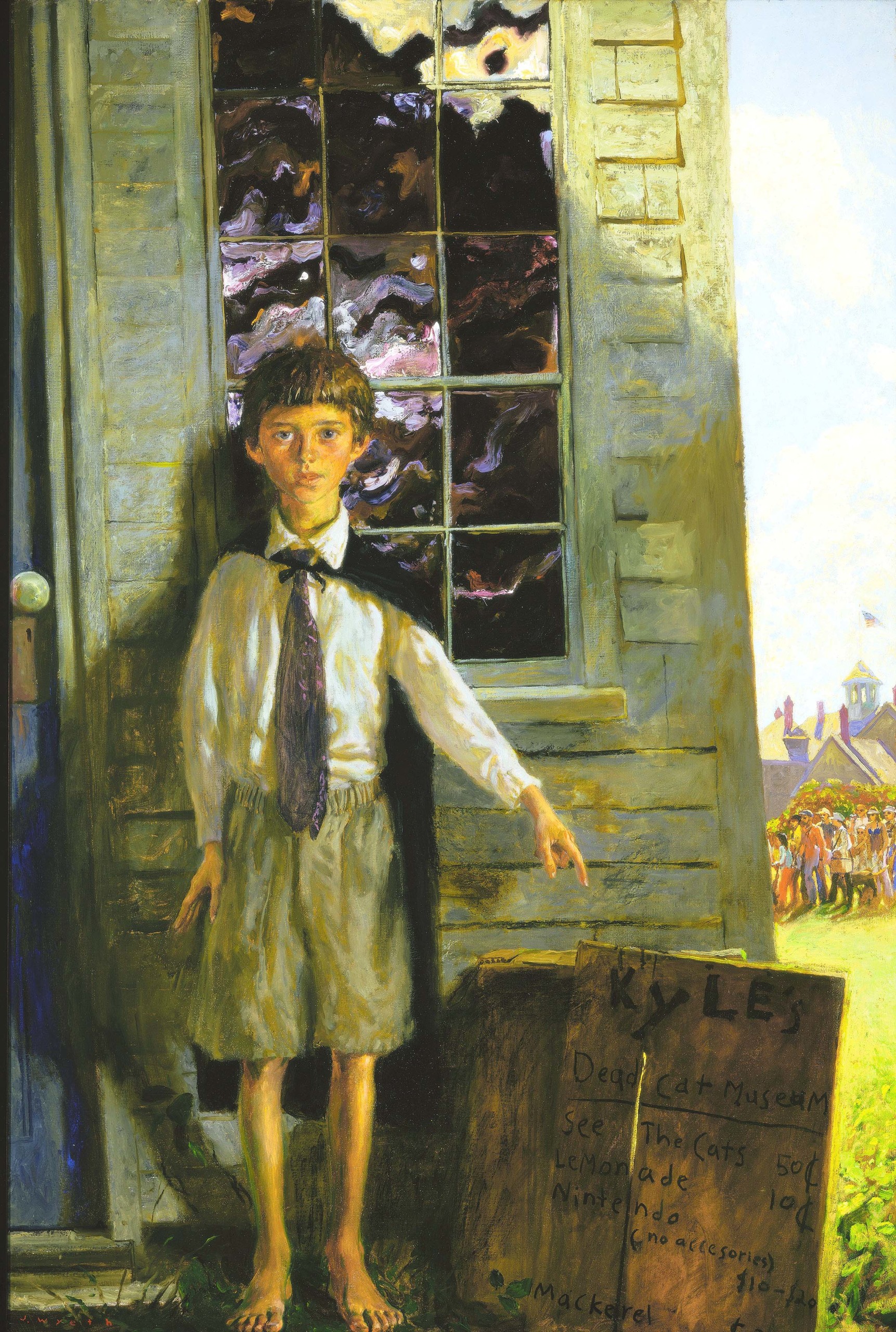

“Dead Cat Museum, Monhegan Island,” 1999, oil on canvas, 60 by 40 inches. Private collection. ©Jamie Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

“Below the Barn” (1965) is rooted in an actual event (the death of a cow, and the need to dispose of its body) and yet what perhaps intensifies the grim scene is the presence of two other very much alive cows who are bearing witness.

In “Dead Cat Museum” (1999), a boy has set up a concession stand and is hawking views of taxidermized cats much as a kid would sell glasses of lemonade for summer pocket change.

Ghosts loom significantly in other paintings — whether it is Andy Warhol sipping consommé from a bowl (“Consommé,” 2013) or the luminaries from his life and friends and family who appear in his mixed-media screen door series, which he began after his father’s death. Even when Wyeth paints a downed sycamore, it is imbued with human characteristics.

Wyeth has reveled in the physical pleasure of working in oil and mixing freer brushwork with his masterly attention to detail. And he takes delight in bringing to life the role of gulls-as-predators, as in his “Seven Deadly Sins” series.

“Consommé,” 2013, enamel, gesso, gouache and watercolor on archival cardboard, 47¼ by 39¼ inches. Greenville County Museum of Art, Greenville, S.C. Purchased with funds through the 2017 art for Greenville campaign and the 32nd Antiques, Fine Art and Design Weekend, presented by United Community Bank. ©Jamie Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

The years in which Jamie came of age were tumultuous, with assassinations, the cold war and, ultimately, protests against the war in Vietnam. As unlikely as it seems, the artist became friends with Andy Warhol and actually worked in the factory for a time. What attracted Jamie to the then-controversial artist, he said, was Warhol’s genuine sense of wonder. While their art could not have been more different, they had bonded and become genuine friends.

Wyeth was more traveled than his father and had studied anatomy and learned lithography during his years in New York City. These skills became part of an extensive artistic tool kit that evolved as an adjunct to the classical teaching he had received from his aunt Carolyn. To this day, he professes he lives and breathes for art…and his best work, he adds, succeeds when and if he becomes utterly absorbed in the character or subject.

“In ‘Jamie Wyeth: Unsettled,’ expect paintings that exude an ominous stillness, with post-apocalyptic skies, frightening shifts in scale, and strange vantage points,” Burdan promises. Wyeth’s paintings may appear to be dreamscapes, but in a flash, they can fuel nightmares.

With the completion of the Farnsworth’s run on September 24, the exhibition will move to The Greenville County Museum of Art in Greenville, S.C. (November 27-February 16), The Dayton Art Museum in Dayton, Ohio (March 15-June 8) and The Frye Art Museum in Seattle, Wash. (July 12-October 5, 2025).

The Farnsworth Art Museum is at 16 Museum Street. For information, 207-596-6457 or www.farnsworthmuseum.org.