Quilt, worked by Priscilla (Ballenger) Leedom, quilter, with a center design by Lewis Halbert, Germantown, Penn., 1861, silk, cotton. Gift of Philip and Noelle Richmond 2020.0006.

By Kristin Nord

WINTERTHUR, DEL. — An iron trivet, a ceramic pitcher, a lantern. These are items one might find in an attic and dismiss as detritus, destined for a tag sale. But, they prove to be objects that are invaluable in bringing “Almost Unknown, The Afric-American Picture Gallery,” an exhibition on view through January 4 at Winterthur, to life.

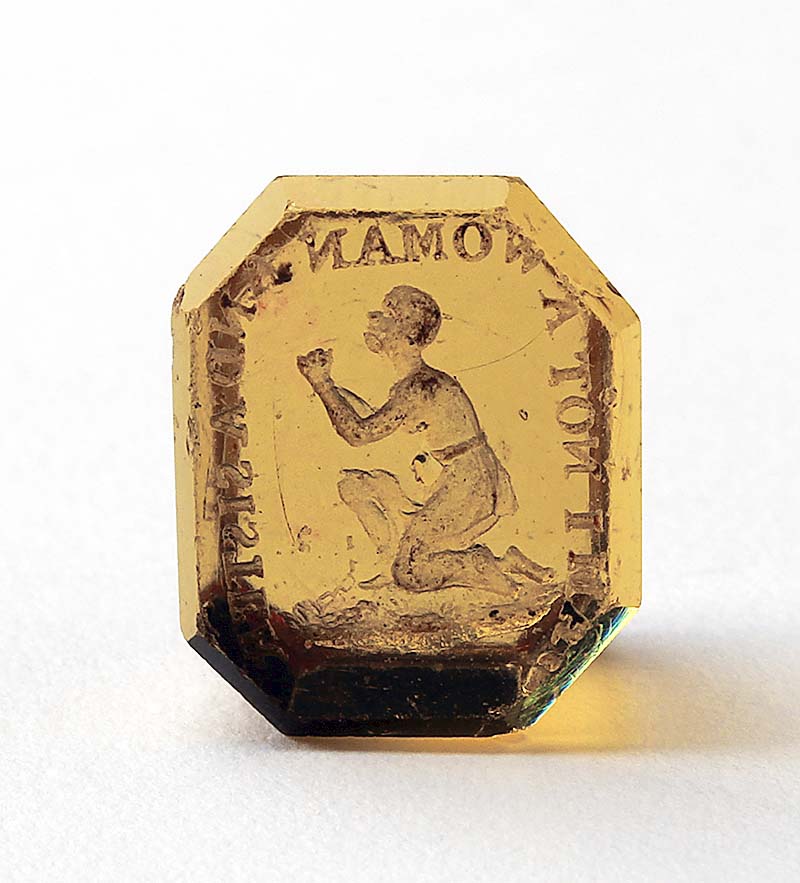

From the trivet, which displays the sankofa, a symbol from the Akan culture in Ghana, to an abolitionist medallion developed in the studios of Josiah Wedgwood that became a global phenomenon, these artifacts harbor a rich lode of rarely told stories. Guest curator Dr Jonathan Michael Square’s aim was to bring to life the words of William J. Wilson, who was born in 1820 and wrote under the pen name “Ethiop” in the 1850s, when he created in a series of essays an imaginary “gallery” — “The Afric-American Picture Gallery,” which gives its name to the exhibition — to celebrate the Black history and culture that has been lost to us or that might have been if slavery never existed.

It is a powerful and complex assignment but one that has particular resonance in the current moment.

Alexandra Deutsch, the John L. and Marjorie P. McGraw director of Collections at Winterthur Museum and Gardens, was familiar with Square’s earlier curatorial work. She was eager to give him artistic freedom to use the museum’s massive collections to explore any theme he chose. An expert in Black fashion history and material and visual culture, Square worked in close collaboration with her and Kim Collison, curator of exhibitions, and called upon the talents of Chuck Mack of Charles Mack Design, Sally Wren Comport and Lindsay Bolin Lowery of Art at Large, Inc. Their efforts have resulted in a show that is rich in the power of theater and steeped in visual references to the culture of the time.

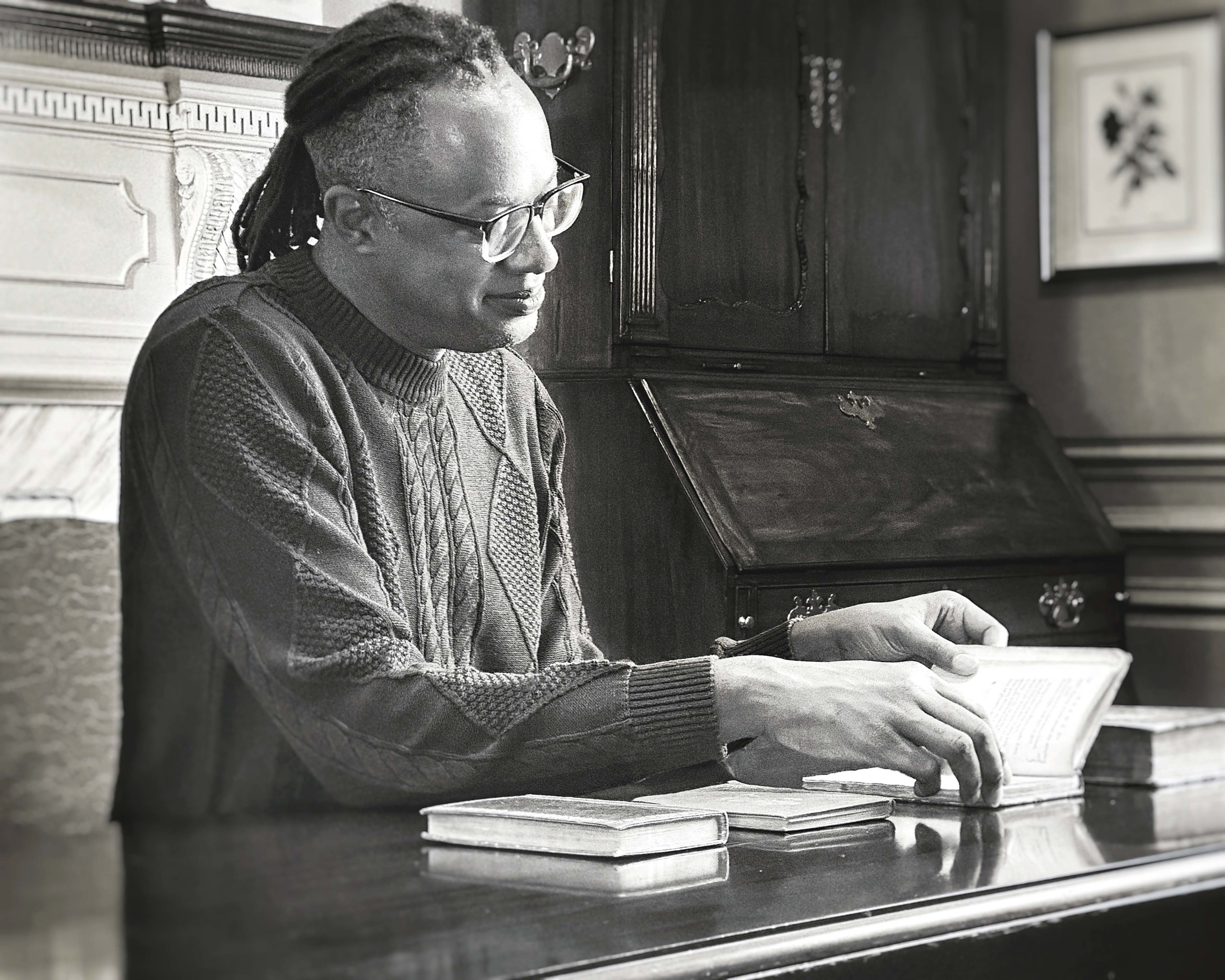

Dr Jonathan Michael Square curated objects from the Winterthur collection.

The end result, Deutsch said, “is an immersive exhibition which embodies the very best of what the collections at Winterthur have the power to do.” It underscores how objects, “one of them as small as a fingernail, can serve as a window into a history and a moment in time you perhaps have never contemplated.”

Just who was William J. Wilson, and what role did he play in the intellectual discourse of his time? A free Black journalist and schoolteacher who lived and worked principally in Brooklyn, N.Y., and Washington, DC, Wilson wrote for many Black periodicals in the 1840s and 50s and had covered people, places and culture as a Brooklyn correspondent for The Frederick Douglass’ Paper. In 1859, writing as Ethiop, he published “The Afric-American Picture Gallery” in several installments in The Anglo-American Magazine.

Square became familiar with “The Afric-American Picture Gallery,” which conjured the imaginary creation of America’s first Black Art Museum, in classes he taught both at Harvard and at Parsons School of Design, where he is an assistant professor of Black Visual Culture. With Deutsch’s encouragement, he spent six months becoming acquainted with Winterthur’s vast holdings before selecting the prints, paintings, sculpture, books and decorative objects that would best inform Wilson’s free-ranging text. Overall, Ethiop’s serialized essay is a curious work, with some sections that move in Psalm-like couplets and others that segue abruptly into the realm of magical realism.

Installation view of “Crispus Attucks, The First American Martyr, 1770” by Charles C. Dawson, et al., Chicago, 1940, plaster, watercolor painting, wood, hardware, LED lights. Collection of Tuskegee University, Gift of Charles C. Dawson.

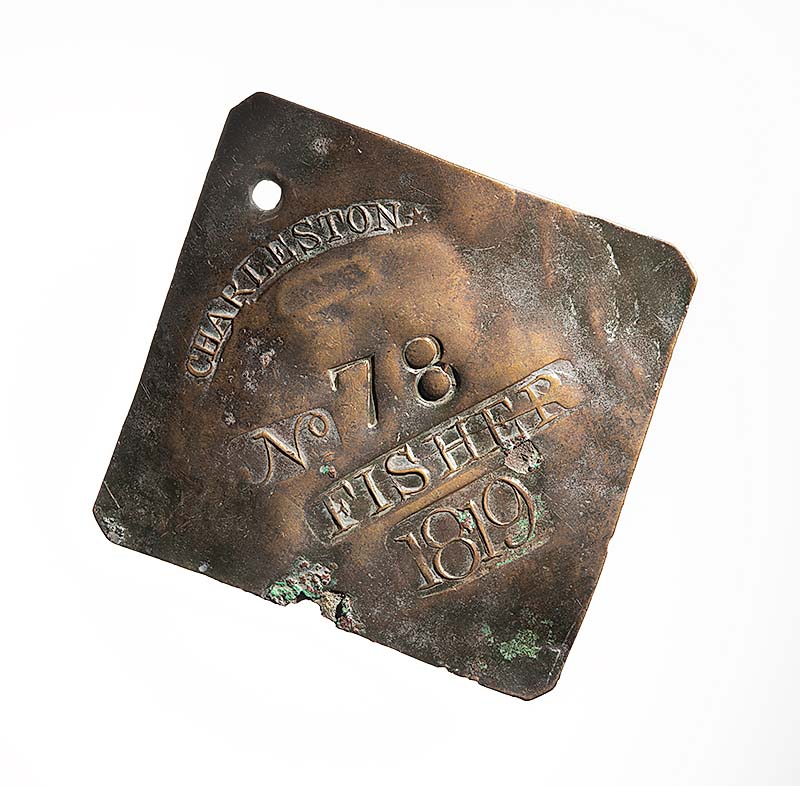

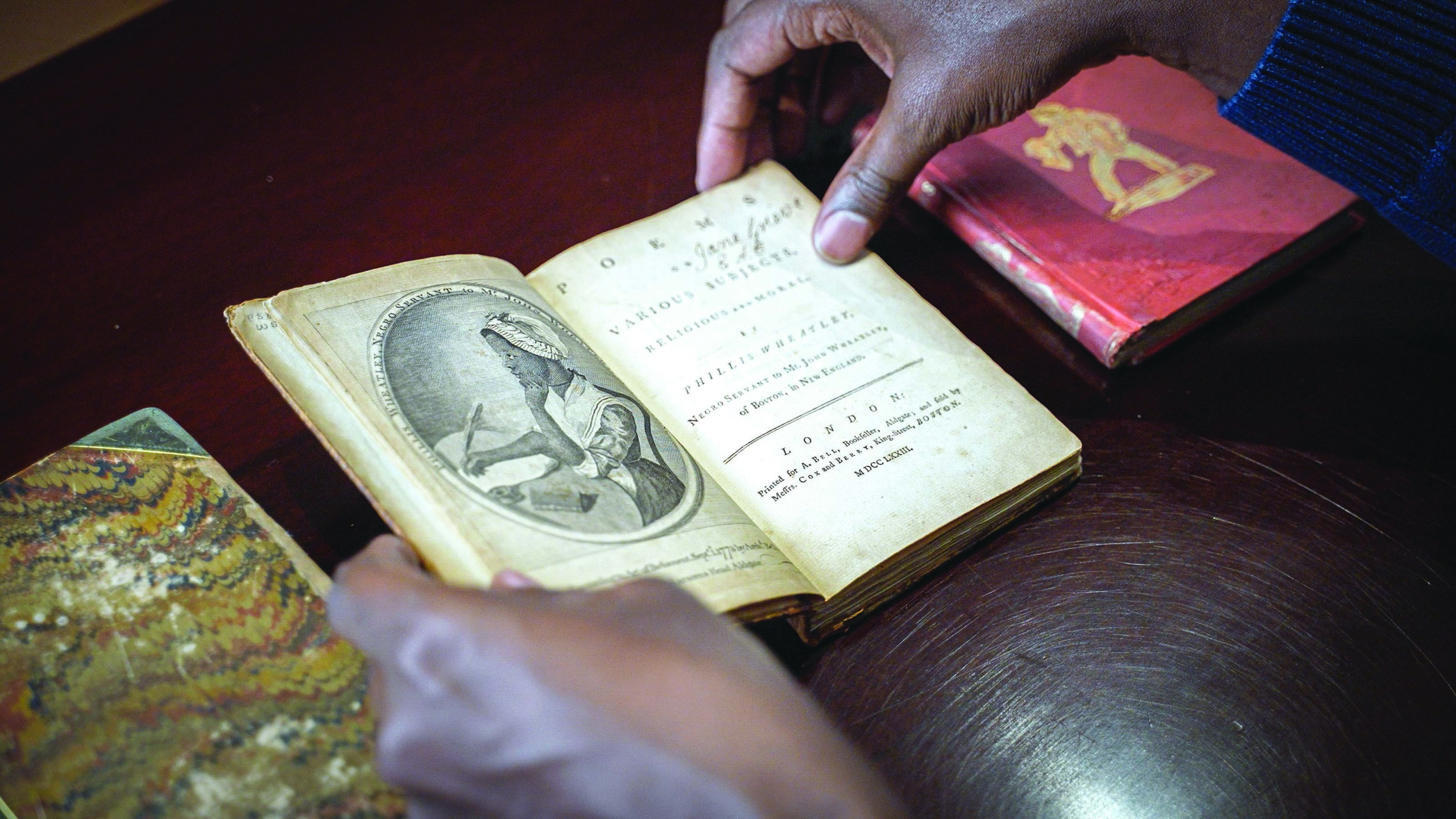

Starting the exhibition is a curated selection of reproductions of The Provincial Freeman, a newspaper published by Mary Ann Shadd (1823-1893), an American-Canadian anti-slavery activist and the first Black woman publisher in North America. Next, we encounter a diorama from the Tuskegee Legacy Museum, depicting the shooting of Crispus Attucks, the first American killed in the American Revolution, then a painting that depicts the arrival of the first slave ship to an American shore: Jamestown Harbor in Virginia. We come face-to-face with a Charleston government-issued slave badge dated 1819 that was designed to systematize and control slave movement. Ethiop would also have us consider early Black leaders, whether Toussaint L’Ouverture, who led the Haitian Revolution and established the first independent Black Republic in the Americas in 1804, or Phillis Wheatley, the first published Black woman poet in the United States.

Soon enough, however, Ethiop challenged shibboleths and spoke truth to power.

George Washington’s prosperity, he notes, was due to his success as a slaveholder. (Square presents a bust of the founding father, one of more than 600 depictions in Winterthur’s collection, on a pedestal of kente cloth, a traditional textile from present-day Ghana that holds particular significance in the African diaspora.) And he foresees a time when Washington’s Mount Vernon will be reduced “to dilapidation and decay.”

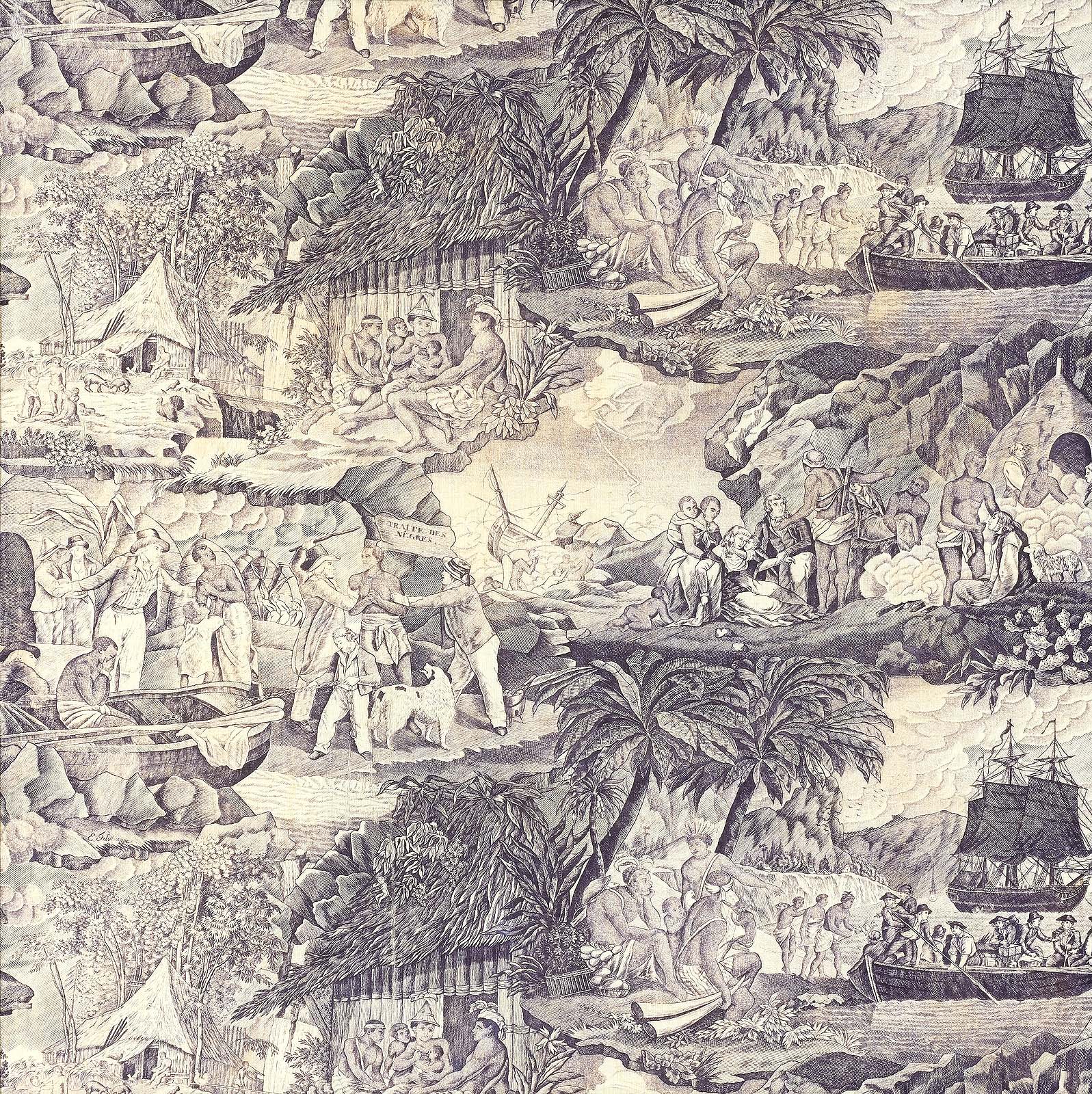

“Traite des Negres (The Slave Trade),” Nantes, France, 1830-40, Designed by Frédéric Etienne Joseph Feldtrappe (1786–1849) after a 1791 engraving by J. R. Smith of a 1791 painting by George Morland called “African Hospitality and Slave Trade.” Cotton Museum purchase 2002.0036.

Next, visitors approach a section titled “The Black Forest,” a mysterious and at times terrifyingly dramatic gallery inhabited by dangerous and eccentric characters of Ethiop’s imagination. Could we be making our way along a portion of the underground railroad? Are we poised to encounter trials worthy of Odysseus? What keys will be needed by those wanderers who enter it searching for freedom?

Square explicates: “‘The Black Forest’ represents the physic geography of the Black experience, establishing a profound connection between American terrain and the intertwined histories of bondage and freedom.”

Much as Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe played a significant role in the United States in shaping public opinion before the Civil War, we see, in the design and execution of a quilt, created collaboratively by the Quaker abolitionist and unionist, Priscilla Ballenger Leedom, and a freed black man named Lewis Halbert, signs that in some households, evolution was underway.

Among Ethiop’s stock characters is a gallery boy whom he identifies as “Tom Onward,” an as yet unformed and roguish youth who is positioned for growth: “let but the culture beam in upon him, change not his physical, but his moral, mental and religious state and then possess him with means — with wealth… and you place beneath him a power and put in his hands a force that will be felt throughout the entire ramifications of human society,” the author wrote.

Sampler worked by Lucy Davis, Freetown, Sierra Leone, 1843, linen, silk. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle. 2018.0007.

“The end will come for the tyrannical wealthy white man who regarded the black man as but a poor imbecile ignorant feeble thing” Ethiop adds.

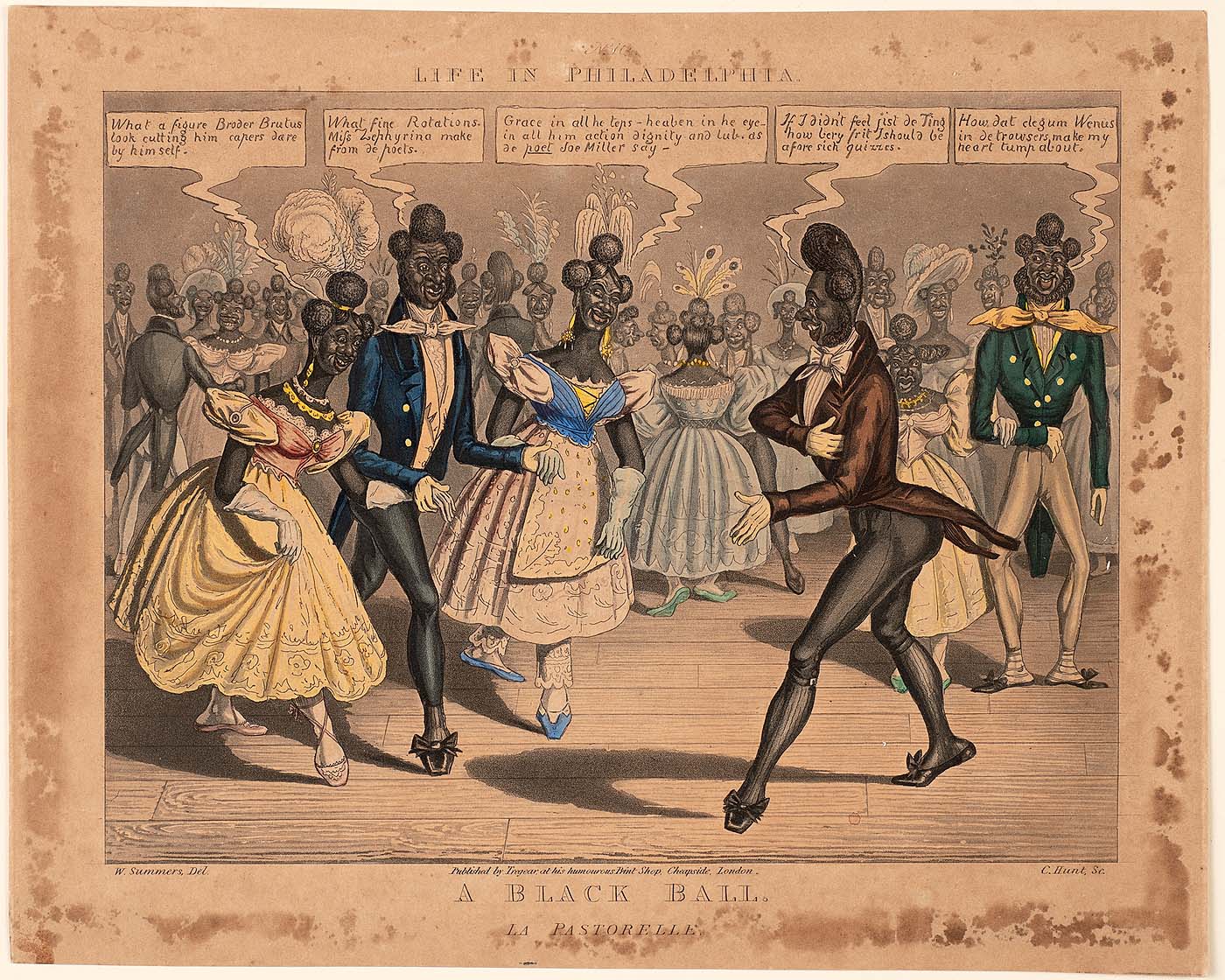

Signs of resistance to progress can be seen in the racist art that was proliferating. Venerable institutions, like the Black Church, Ethiop notes, persisted in preaching that submission and obedience to one’s slave master remained the Christian duty of his race. One need only encounter the sampler made by young African missionary schoolgirl Lucy Davis in Sierra Leone, to grasp how deeply such lessons have sunk in: “We love the Lord he came to save / Poor Negro from the sinner’s grave / Though we are black and mean and vile? Lord Jesus on poor negro smile.”

The American Colonization Society pushed for repatriation of slaves — as pictured in the idyllic “View of Cape Palmas, Maryland in Liberia” but it fails to tell the more truthful story — that those freed blacks who sought liberation in Africa would face high mortality rates.

“I want people to understand the complexity of intellectual history amongst elite African Americans in the Nineteenth Century,” Square says, “and William J. Wilson was very much a part of that.” Additionally, he says, while major figures like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman are taught in today’s history classes, there are many lesser-known black intellectuals and heroes who should be studied.

Antislavery or abolitionist seal, London, 1820-40, glass. Gift of Lindsay Grigsby. 2009.0014.001.

The drumbeat of the Abolitionist movement was growing louder, and can be seen in not only the literature but in Josiah Wedgwood’s sample pitcher, decorated with its anti-slavery slogans. Wedgwood, the great manufacturer of English ceramics, was an ardent abolitionist and leader member of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade. His creation and distribution of the isolationist medallion made it a galvanizing symbol.

And seeds of hope can be found in the Colored Conventions movement. Wilson had been a key writer of the opening speech of the 1855 National Colored Convention in Philadelphia. These gatherings were held between the 1830s and the 1890s and became crucial forums for discussions on abolition, suffrage, education.

In subsequent writing, Wilson urged his readers to “begin to tell our own story, write our own lecture, paint our own picture, chisel our own bust.”

Square returns us to the sakofa, with which he began this excursion, to ask: “What family heirloom, what treasured artifact, might you place in our Afric-American Picture Gallery? Consider an object that speaks to the soul of this nation — a testament, perhaps, to lives lived and lost, to courage unspoken or to dreams long deferred. What object would you offer to honor our ancestors and instruct present and future generations?”

“Almost Unknown, The Afric-American Picture Gallery” is on view through January 4.

Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library is at 5105 Kennett Pike. For information, 800-448-3883 or www.winterthur.org.