“Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1” by Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), 1932, oil paint on canvas, 48 by 40 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Ark. —Edward C. Robison III photo ©2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS, London

LONDON — Tate Modern recently opened the largest retrospective of Modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) ever to be shown outside of the United States. Marking a century since O’Keeffe’s debut in New York in 1916, it is the first UK exhibition of her work for more than 20 years. This wide-ranging survey, which remains on view until October 30, reassesses the artist’s place in the canon of Twentieth Century art and reveals her profound importance. With no works by O’Keeffe in UK public collections, the exhibition is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for European audiences to view her oeuvre in such depth.

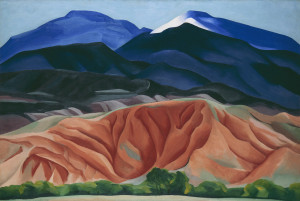

“Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II,” Georgia O’Keeffe, 1930, oil on canvas mounted on board, 24¼ by 36¼ inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, gift of the Burnett Foundation. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Widely recognized as a founding figure of American Modernism, O’Keeffe gained a central position in leading art circles between the 1910s and the 1970s. She was also claimed as an important pioneer by feminist artists of the 1970s. Spanning the six decades in which O’Keeffe was at her most productive and featuring more than 100 major works, the exhibition charts the progression of her practice from her early abstract experiments to her late works, aiming to dispel the clichés that persist about the artist and her painting.

Opening with the moment of her first showings at 291 gallery in New York in 1916 and 1917, the exhibition features O’Keeffe’s earliest mature works made while she was working as a teacher in Virginia and Texas. Charcoals such as “Special No. 9,” 1915, and “Early No. 2,” 1915, are shown alongside a select group of highly colored watercolors and oils, such as “Sunrise,” 1916, and “Blue and Green Music,” 1919. These works investigate the relationship of form to landscape, music, color and composition, and reveal O’Keeffe’s developing understanding of synaesthesia.

A room in the exhibition considers O’Keeffe’s professional and personal relationship with Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946); photographer, Modern art promoter and the artist’s husband. While Stieglitz increased O’Keeffe’s access to the most current developments in avant-garde art, she employed these influences and opportunities to her own objectives. Her keen intellect and resolute character created a fruitful relationship that was, though sometimes conflictive, one of reciprocal influence and exchange. A selection of photography by Stieglitz is shown, including portraits and nudes of O’Keeffe as well as key figures from the avant-garde circle of the time, such as Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) and John Marin (1870–1953).

“Georgia O’Keeffe” by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), 1918, photograph, palladium print on paper. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. ©The J. Paul Getty Trust

Still life formed an important investigation within O’Keeffe’s work, most notably her representations and abstractions of flowers. The exhibition explores how these works reflect the influence she took from Modernist photography, such as the play with distortion in “Calla Lily in Tall Glass — No. 2,” 1923, and close cropping in “Oriental Poppies,” 1927. A highlight is “Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1,” 1932, one of O’Keeffe’s most iconic flower paintings.

O’Keeffe’s most persistent source of inspiration however was nature and the landscape; she painted both figurative works and abstractions drawn from landscape subjects. “Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out of Black Marie’s II,” 1930, and “Red and Yellow Cliffs,” 1940, chart O’Keeffe’s progressive immersion in New Mexico’s distinctive geography, while works such as “Taos Pueblo,” 1929/34, indicate her complex response to the area and its layered cultures. Stylized paintings of the location she called the “Black Place” are at the heart of the exhibition.

“Georgia O’Keeffe” is curated by Tanya Barson, curator, Tate Modern, with Hannah Johnston, assistant curator, Tate Modern. The exhibition is organized by Tate Modern in collaboration with Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna and the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. It is accompanied by a catalog from Tate Publishing and a program of talks and events in the gallery.

Tate Modern is at Bankside. For information, +44 20 7887 8888 or www.tate.org.uk.