Butter churn by Thomas Mitchel Chandler, Jr (1810-1854), 1829, Baltimore, salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt decoration, 10¾ inches high. The William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation. “This is the only signed piece we have of Chandler’s time in Baltimore, before he went to Edgefield, S.C., to make alkaline-glazed pieces. And it’s an Eastern Shore, Va., landscape, which makes it dear to Bill and Susan’s hearts,” Hunter says. Scholar Katherine C. Hughes wrote about the work for the MESDA Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts in 2018.

By Laura Beach

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. — The proverbial three-legged stool — scholars, collectors and the trade — supporting every robust collecting category is especially evident these days in the field of American pottery. From the annual journal Ceramics in America to the specialty auctioneer Crocker Farm, these and other industry influencers are making pottery a bright spot in the broader market for American antiques.

Some of the best pieces of Southern pottery to surface recently are, with the guidance of ceramics authority Robert Hunter, making their way into the collection of William C. “Bill” and Susan S. Mariner, and from there to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), where objects from the Mariners’ private foundation are on long-term display in the Southern Ceramics Gallery bearing their name. Opened in 2015 on the occasion of MESDA’s 50th birthday and revised in 2024, the thoroughly engaging, deeply immersive installation continues to evolve.

The Mariners — who also support Colonial Williamsburg and, through their foundation, lend to museums nationally — are cherished members of the MESDA family, so much so that the highlight of a recent trip by MESDA Summer Institute students was to the couple’s primary residence near the historic enclave of Berlin, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Featured in the case titled “Tradition” are, rear, a lead-glazed earthenware bowl by Peter Bell, Winchester, Va., 1824-30, and front left, lead-glazed earthenware jar by Andrew Duche, Savannah, Ga, 1736-43, both from the MESDA collection. On loan from the Mariners, left to right, are a salt-glazed stoneware jar by Emanuel Suter, Rockingham County, Va., 1850-60, and the stencil used to decorate it; and an alkaline-glazed stoneware bottle by Abner Landrum, Edgefield County, S.C., 1820. The large lead-glazed earthenware jar, right, by Mary Adam, Hagerstown, Md., 1819-25, belongs to MESDA.

“When MESDA registrar Jessie Harris and I packed up Southern pottery from the Mariner collection a decade ago, we emptied their shelves and fireplaces. On our recent return with students, it was amazing to see both full again. Bill and Susan have acquired more great Southern objects, plus some Northern ones. They will never stop collecting,” says Johanna Brown, chief curator and director of collections, research and archaeology at Old Salem Museums and Gardens and MESDA.

Aligned with their commitment to historic preservation, the Mariners’ love of antiques spans decades. “Bill and I have always gravitated to old things. We are both from this area and have known each other forever. Bill is a direct descendant of the first priest at St Martin’s Church, built in 1756 in nearby Showell, Md.,” Susan says. From Eastern Shore decoys to portraiture and paint-decorated furniture, their collecting interests are wide ranging. Ceramics, ancient and medieval to contemporary — the latter including work by Michelle Erickson, David Stuempfle and Jugtown — predominate. “We put a wing on to hold everything,” Susan confesses with a laugh.

It was on a visit to Yorktown, Va., in the late 1990s that the Mariners wandered into Period Designs. Drawn to a stoneware jar with a lopsided rim and vivid cobalt blue decoration of a masted war ship, the couple fell into conversation with the shop’s proprietor, Robert Hunter. They purchased the pot made by Elisha Parr of Baltimore around 1825.

Jar by Elisha Parr, Baltimore, 1820-30, salt-glazed stoneware, 15-3/8 inches high. The William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation. On their first visit to Robert Hunter’s shop, the Mariners purchased this vessel by Parr, who probably learned the technique of incised cobalt decoration during his three-year partnership from 1815 to 1818 with William Myers and his association with Henry Remmey at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory.

“Our name is Mariner, so naturally we had to have it. Rob later gave us the first volume of Ceramics in America. He said, ‘don’t just look at the pictures, read it.’ We did. We’re not scholars by any stretch of the imagination, we’re collectors, but ceramics became a real passion for us after that,” Susan says.

On subsequent visits to Period Designs, Bill would ask, “What’s the best thing you have?” Hunter would say, “Well, Bill, it’s probably upstairs in my office and it’s probably too expensive.” The collectors were undeterred. As Hunter, the founding editor of Ceramics in America, notes, “I had an inside track on certain things that were going to be important. The Mariners made highly discriminating purchases of primarily Southern stoneware and earthenware. Among their acquisitions are many seminal objects.”

Bill acknowledges, “We discovered a long time ago that it’s better to buy the best, even if we have to wait for it. With Rob’s guidance, we’ve acquired the best we can.”

The Mariners got to know MESDA when they lent a slip-decorated barrel flask (top center) from Alamance County, N.C., to the 2010-13 traveling exhibition “Art in Clay: Masterworks of North Carolina Earthenware,” co-sponsored by Old Salem Museums and Gardens, Chipstone Foundation and the Caxambas Foundation. When the couple began contemplating how they might share their treasures with the public, Hunter thought of MESDA, where he had close ties with Robert Leath, then chief curator and vice president of archaeology, collections and research.

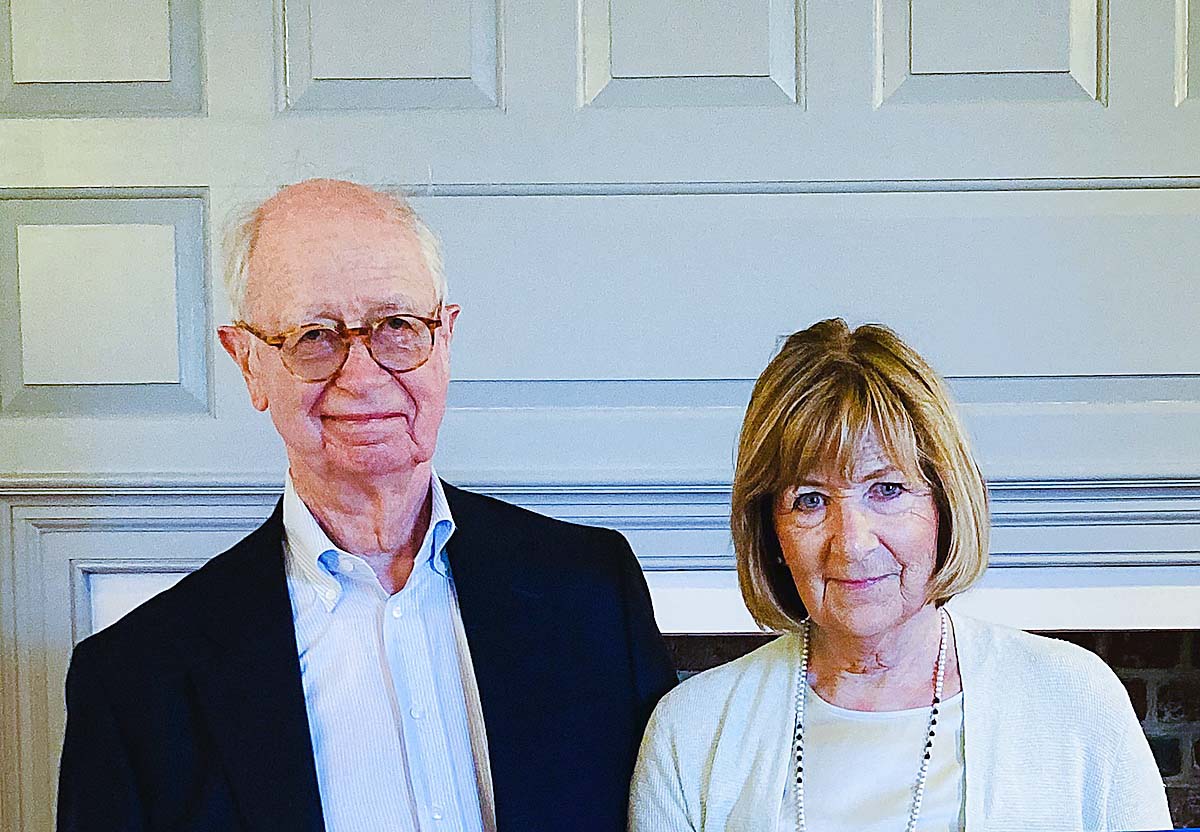

Bill and Susan Mariner have long worked to preserve the historic architecture of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Susan serves on the board of directors of Rackliffe House, where this photo was taken.

Susan recalls, “When Robert [Leath] and MESDA curator Daniel Ackermann first came to our house I think they were a bit surprised. They said, ‘yes, well, we can do something.’ Once we got talking, MESDA agreed to convert an auditorium to make a gallery large enough to display the ceramics collection. Having everything on view was one of our conditions.”

Adjacent to MESDA’s Carolyn and Mike McNamara Southern Masterworks Gallery, Thomas A. Gray Rare Book and Manuscript Collection and the Dianne Furr Moravian Decorative Arts Gallery, the Mariner Southern Ceramics Gallery answers an institutional need. Brown says, “Formerly, the only way to see our collections were in room settings on guided tours. As audiences changed, it became clear that people wanted self-guided experiences. We began developing the idea of galleries that could serve that purpose. Our ceramics holdings are diverse and particularly rich in North Carolina material. With loans from the Mariner collection, we are able to expand the stories we tell about ceramics production in the South.”

Mingling 105 ceramic objects from the Mariner foundation with the institution’s own collections and a smattering of loans from other sources, the Southern Ceramics Gallery houses the most comprehensive collection of antebellum pottery made in Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee and, since 2022, Alabama. Labels for the debut presentation were written by guest curator Hunter in collaboration with Leath, Ackermann, Brown and Brenda Hornsby Heindl; Jim Armbruster of Colonial Williamsburg designed the original installation. As shown in MESDA’s online virtual view, the exhibits explore Southern pottery by medium — lead-glazed earthenware, salt-glazed stoneware and alkaline-glazed stoneware — and by maker, place and date. Pots housed in freestanding cases in the room’s center illustrate themes of tradition, design, expression, purpose, faith, war and freedom.

Southern stoneware is celebrated for the range of colors and textures of its alkaline and salt-glazing. Located at the entrance to the Mariner Gallery, this pyramidal display, dubbed “Glazes of Glory” by the curators, highlights the appeal and diversity of Southern stoneware.

Before taking up his new post as director of Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens in Houston in 2024, Ackermann and his MESDA colleague Lea Lane, working with Hunter, revised the gallery, notably adding pottery from Alabama. Ackermann and Lane’s companion show “Thrown Together: Pots & People of Early Alabama” remained on view at MESDA through September 2023. Of the expansion, Brown explains, “Potters moved west, taking techniques and traditions with them. To tell a more complete story of Southern ceramics, we’ve broadened our approach.”

For the updated display, designer Hannah Jean Crowell revamped several existing elevations, among them the first, pyramidal exhibit, nicknamed “Glazes of Glory” by the curators, who sought to emphasize the formal variety and often spectacular coloration and texture of Southern pottery. Balancing didacticism with aesthetics, organizers added more panel text throughout the gallery.

Mariner treasures are many and varied. Among them is an alkaline-glazed stoneware bottle incised “July 20th 1820 / A. Landrum.” It is the earliest known example of dated Edgefield, S.C., stoneware by Abner Landrum, who established his pottery around 1815 and was the owner of the Edgefield Hive, where enslaved potter David Drake, whose work is also in the Mariner collection, likely learned to read and write.

From the MESDA collection, the monumental jar at left is by David Jarbour (1788-circa 1841). Born into slavery, Jarbour worked in the Alexandria, Va., stoneware industry under Lewis Plum, progenitor of the Wilkes Street Pottery, where he trained alongside the white potter John Swann. He ultimately purchased his freedom from merchant Zenas Kinsey, a Quaker abolitionist, in 1820. Inscribed on base: “1830 / Alexa / Maid By / D. Jarbour.” Salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt decoration, 27¾ inches. Gift of Mr and Mrs Byron J. Banks.

“Virtually every piece acquired by the Mariners has the potential for being a new discovery and a catalyst for research that’s groundbreaking and important,” says Hunter, citing an alkaline-glazed stoneware face jug attributed to John Wesley, newly identified by Hunter and Brandt Zipp as a Black potter born enslaved in South Carolina.

Purchased at Mebane Auction in North Carolina last year, a four-gallon food storage jar by Benjamin DuVal & Company of Richmond, Va., 1811-17, is decorated with a sturgeon, an homage to what was once a critical source of nutrition for Virginia’s indigenous people.

Inveterate pot hunters, the Mariners traveled to Tennessee to claim a large signed and dated watercooler of 1847 by Henderson County maker William R. Craven, who incised an owl’s head — and least there be any doubt, the word “owl” — on the vessel’s side. Other Tennessee pieces include a Christopher Haun of Greene County ring bottle and earthenware jar. The latter’s bold, abstract glazing recalls the mid Twentieth Century vessels of Japanese studio potter Shoji Hamada. Accused of being a Union Army sympathizer, Haun was hanged by the Confederates in 1861.

Also of Civil War interest and formerly in the collection of dealer Rex Stark is a salt-glazed stoneware jar newly reattributed to the Keesee & Parr Pottery of Richmond, Va., circa 1861. As detailed in “At the End of a Rope: A Stoneware Jar and Political Frustration” by Gerstenecker, Hunter and Russ in Ceramics in America 2023, this extraordinary vessel is decorated with the initials “C.S.A” for Confederate States of America and a figure, apparently Abraham Lincoln, swinging from gallows. “If you had told me such a thing existed, I’d have said you were nuts. It’s just an amazing piece of social history,” Hunter marvels.

Students and faculty from the MESDA Summer Institute recently visited Susan and Bill Mariner, seated, at their home on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. From left to right (standing), Terry Taylor, Melissa Bertram, Lea Lane, Katherine Gergory, Tessa Payer, Savannah Gross, Meghan Townes, Allison Donoghue, Torren Gatson, Sarah Beach, Johanna Brown, Sarah Brokenborough, Rob Hunter, Michelle Erickson.

No static enterprise, the Southern Ceramics Gallery is the backdrop for the jointly hosted MESDA-Colonial Williamsburg Ceramics Symposium, which annually alternates between the two museums. The 2026 program is planned for June 4-6 in Virginia, roughly coinciding with the opening of Colonial Williamsburg’s new Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Archaeology Center.

The Mariners’ interest in ceramics extends west to Texas, a state beyond MESDA’s scope. In 2023, they purchased an important Texas jug decorated in the Edgefield style with the face of an African-American woman. Brandon Pratt of Cagle Auction in Georgia flew to Texas to obtain the work after the jug surfaced on Facebook. The jug is now on loan to Colonial Williamsburg. Hunter says, “It’s an important pathway to future research that tells the story of the Edgefield-to-Texas diaspora by enslaved potters.”

Sharing pottery is almost as satisfying to the Mariners as acquiring it. Susan says, “When I’m in the gallery, I can’t help engaging with visitors. We start talking and they get interested. That’s been fun.” Her enthusiasm is echoed by Brown, who says, “It’s a real honor and privilege to show the Mariners’ amazing collection and use it for study purposes. It dovetails beautifully with the ceramics collection established by MESDA founder Frank Horton and strategically expanded since the museum opened in 1965.”

Home to MESDA, the Frank L. Horton Museum Center is at 924 South Main Street in Winston-Salem. For more information, www.mesda.org or 336-721-7360.