EDITOR’S NOTE: AT PRESS TIME, THE SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM WAS CLOSED DUE TO THE GOVERNMENT SHUTDOWN. PLEASE CALL 202-633-7970 BEFORE VISITING

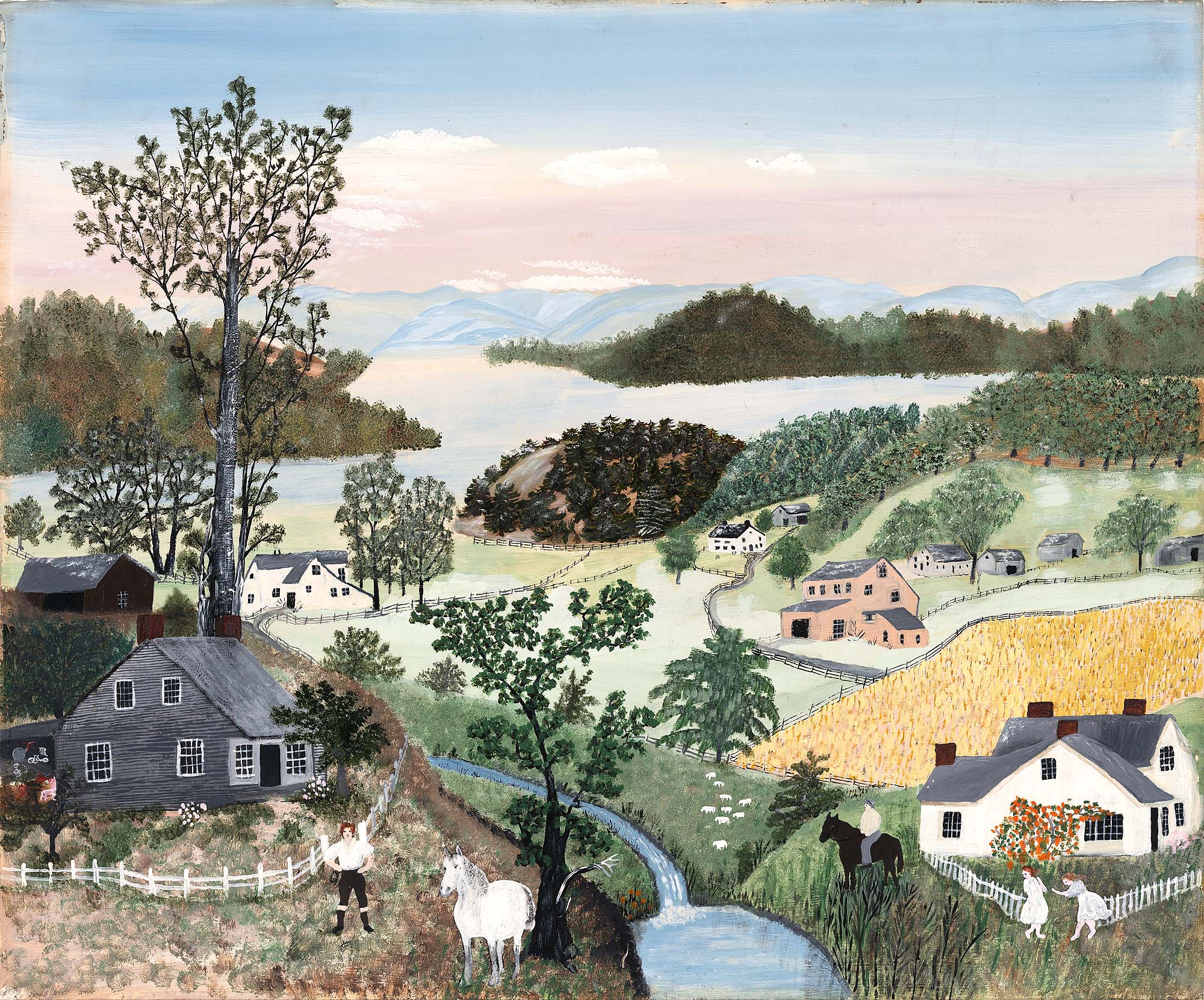

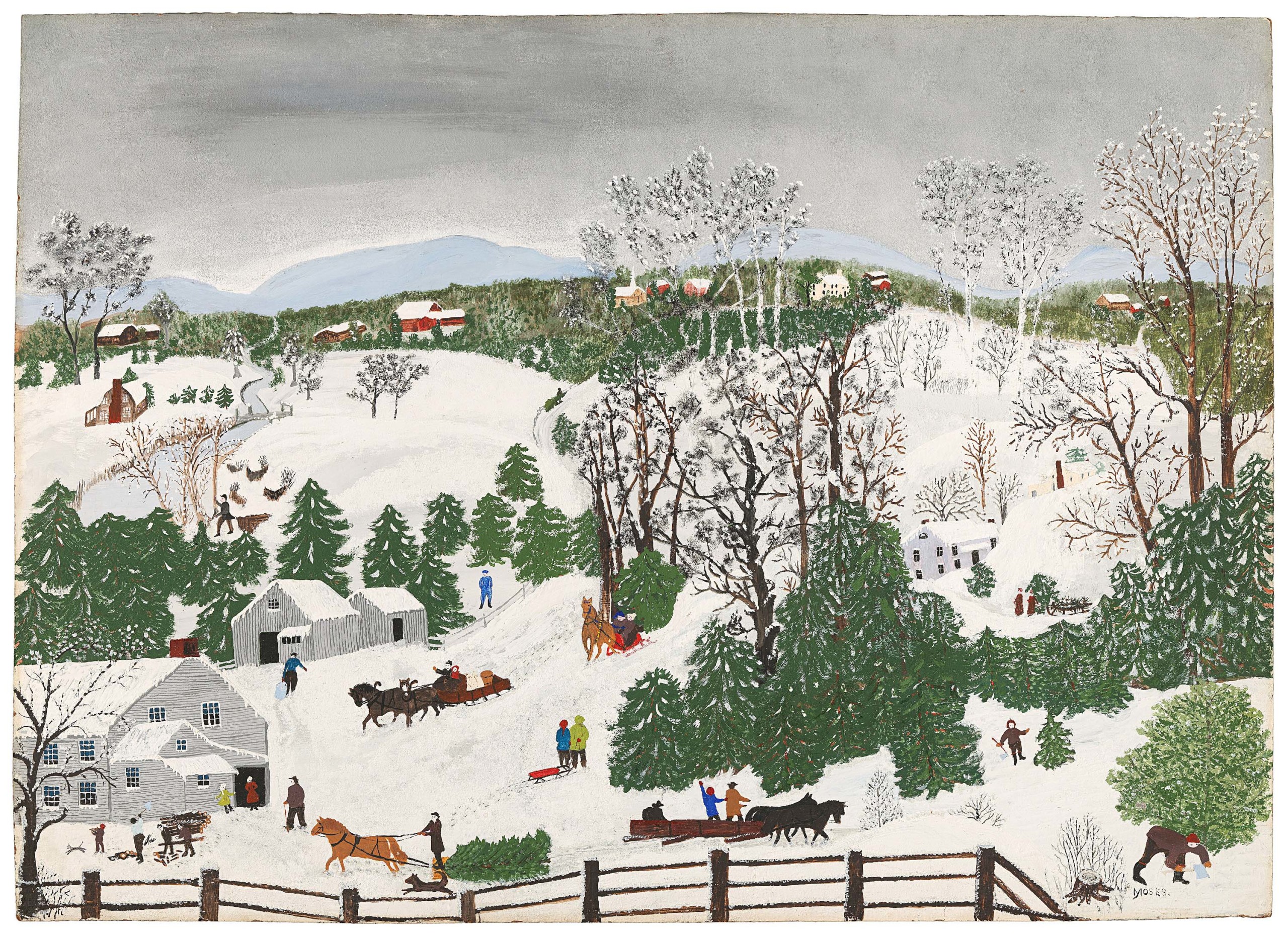

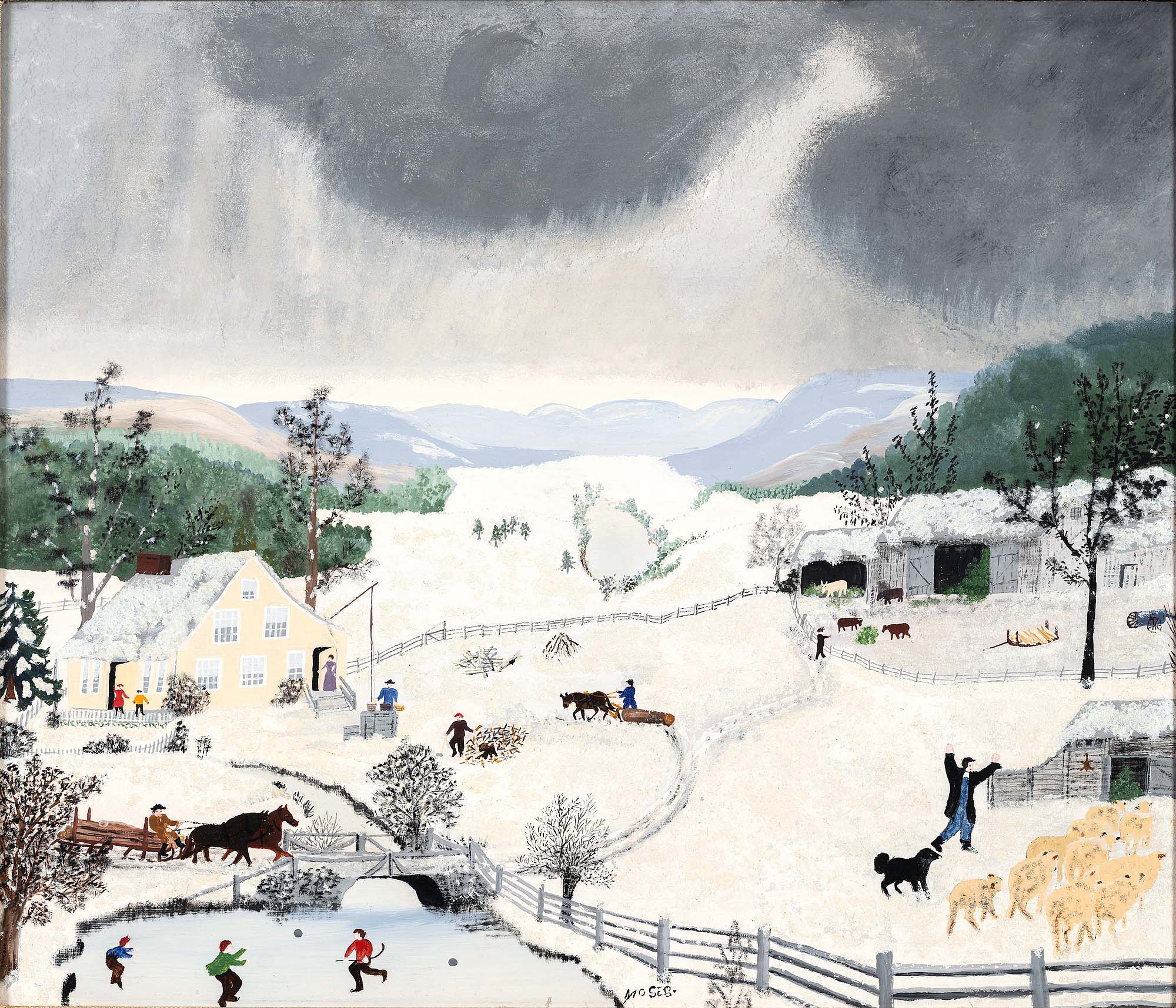

“Grandma Moses Goes to the Big City” by Grandma Moses, 1946, oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Kallir Family in memory of Otto Kallir, 2016.51. © Grandma Moses Properties Co., N.Y.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

WASHINGTON, DC — Anna Mary Robertson Moses (American, 1860-1961), known fondly as “Grandma Moses,” has long been recognized as a singular figure by folk art collectors for her observational landscapes, painted largely between the late 1930s and her death in 1961, at a time when modern art was considerably less pictorial and traditional. A reappraisal of her work and legacy has been in the works for some time and has opened the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) for a nearly nine-month run.

The presentation — 88 paintings created mostly in the final 30 years of Moses’ life and drawn from the museum’s holdings and loans from private collections and public institutions — was organized by Leslie Umberger, SAAM’s senior curator of folk and self-taught art, and Randall R. Griffey, the museum’s head curator.

“When I became SAAM’s first curator of folk and self-taught art in 2012, I noticed that Moses was absent from the museum’s collection. I sought out Jane Kallir, knowing that her grandfather, Otto Kallir, had worked closely with Moses over the course of her painting career, and that Jane was stewarding both Moses’s artistic legacy and grandfather’s work promoting self-taught artists. The reality was that even though Moses had become a household name and arguably more famous than other female painters of her day, major museums still regularly sidelined her. SAAM has long championed self-taught artists and it seemed fitting that it should commit deeply to Moses as a major American artist; she was more than overdue,” Umberger told Antiques and The Arts Weekly. “From that springboard, an exhibition aiming to reposition Moses within, and as a critical part of, the larger American art story took shape.”

Grandma Moses painting in the room behind her kitchen, photo by Ifor Thomas, 1952. © Grandma Moses Properties Co., N.Y.

SAAM’s presentation builds on existing scholarship, both that which was done closer to her lifetime, and more recently, including Karal Ann Marling’s Designs on the Heart: The Homemade Art of Grandma Moses (2006) and Gatecrashers: the rise of the self-taught artist in America by Katherine Jentleson (2020). However, the accompanying eponymous catalog for the show is a pioneer in the research by digging more deeply into her life story that was a backdrop to her art, framing her within her contributions to the American landscape painting genre, exploring the relationship she had with her gallerist Otto Kallir and situating her within the context of the “worker culture” of other American artists working in the 1930s.

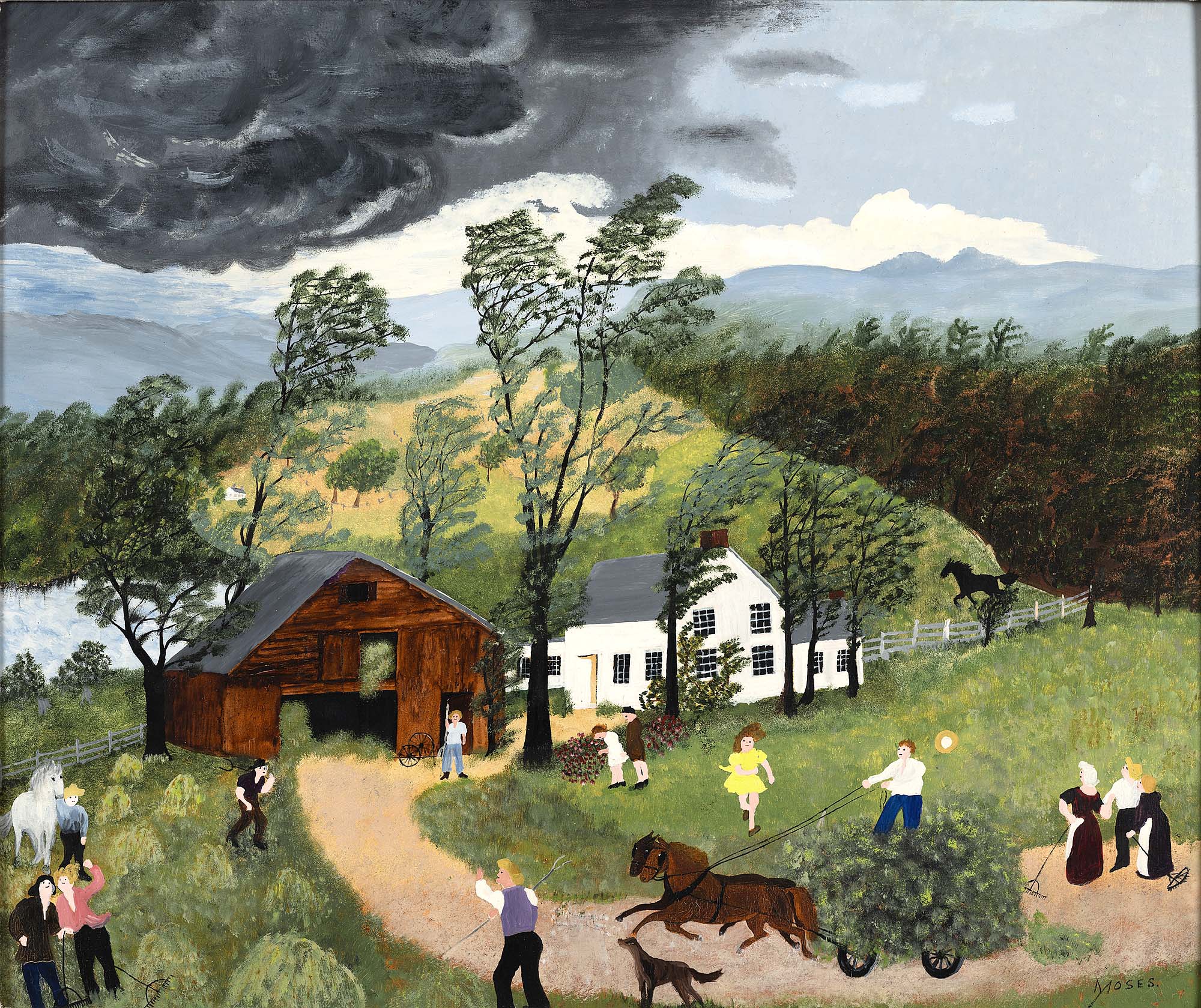

Umberger noted being surprised at seeing Moses’ paintings of storms and forest fires, such as those seen in “Thunderstorm”: “vivid ruminations on natural world turbulence that never had the same kind of media attention that the more cheerful scenes had.” Some of these are in the exhibition’s first section, titled “The Eye of the Storm.”

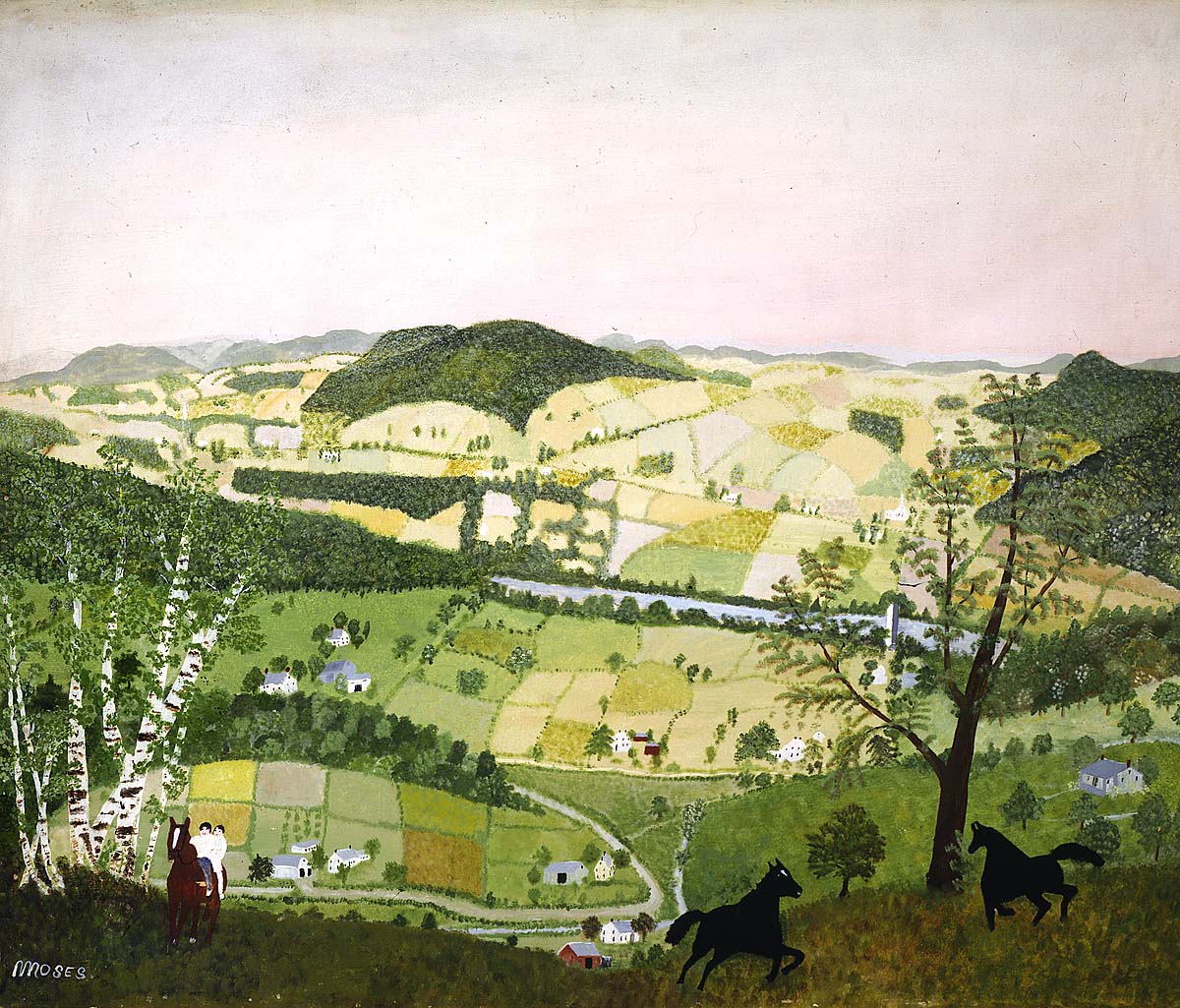

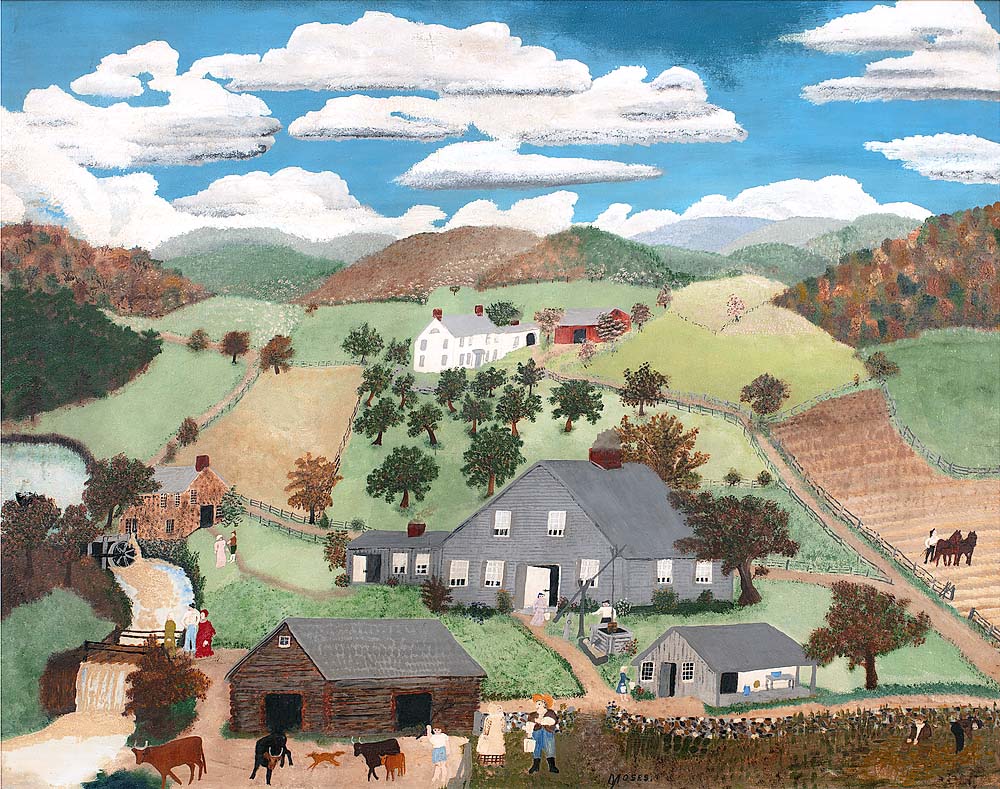

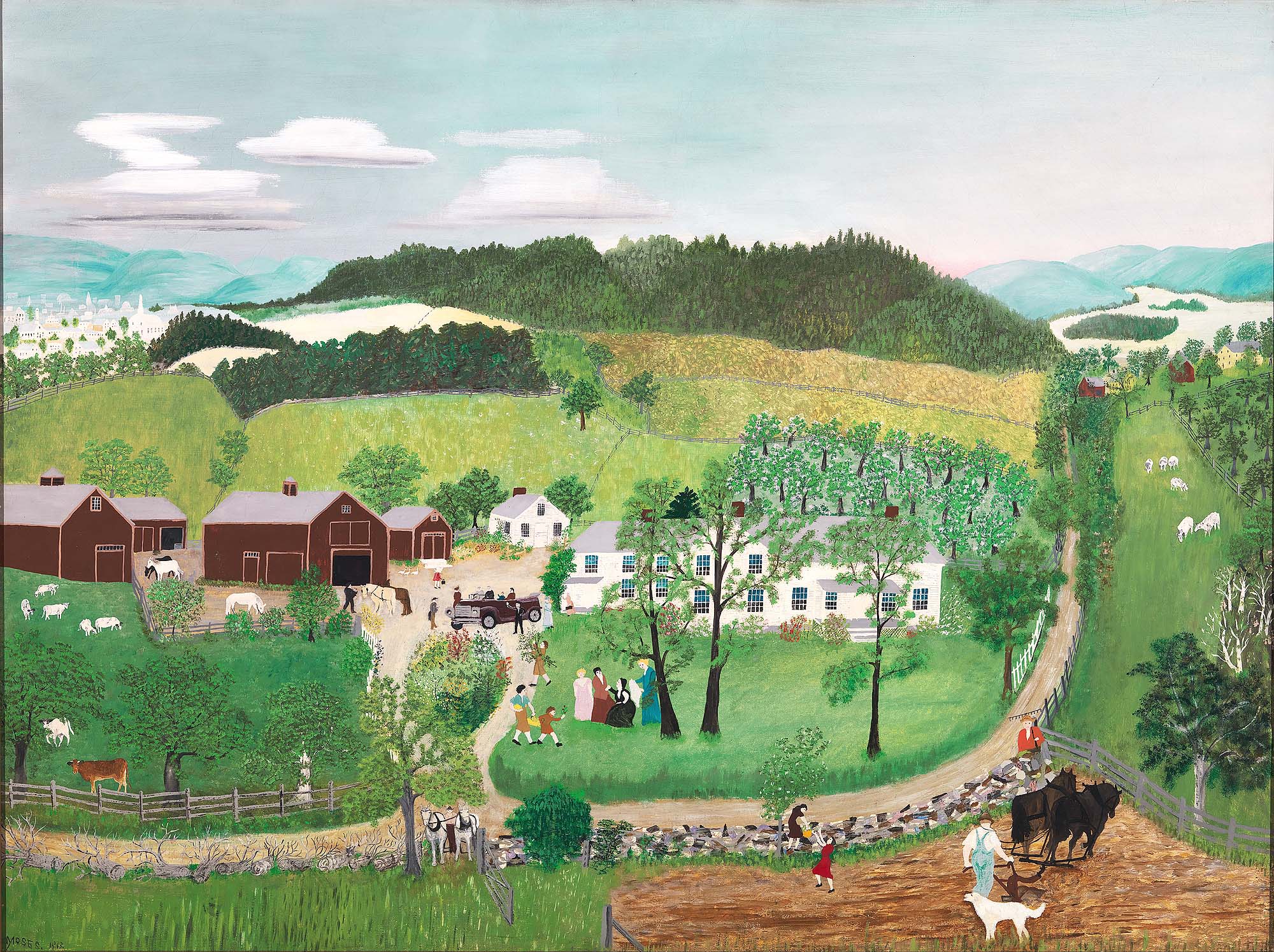

Moses’ early life is delved into more deeply in the second section, captioned “My Life’s History.” Here, works draw on Moses’ memories of her early life in Washington County, N.Y., and include paintings such as “Old Oaken Bucket,” captioned after the title of a popular Nineteenth Century song, and “Cambridge Valley”; in both, the landscape unfolds like a patchwork quilt.

“Cambridge Valley” by Grandma Moses, 1942, oil on high-density fiberboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Kallir Family in Memory of Otto Kallir, 2021.71.1. © Grandma Moses Properties Co., N.Y.

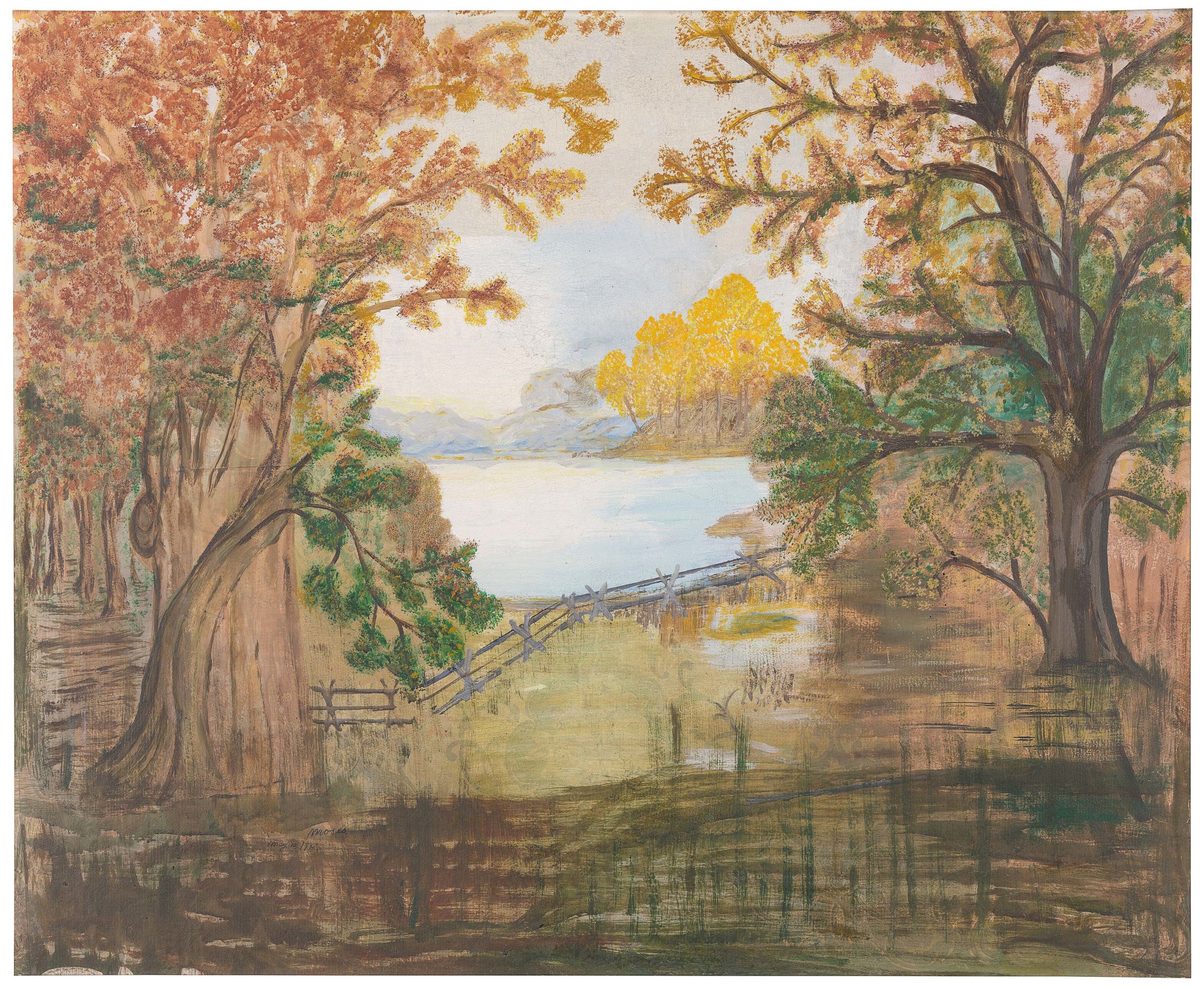

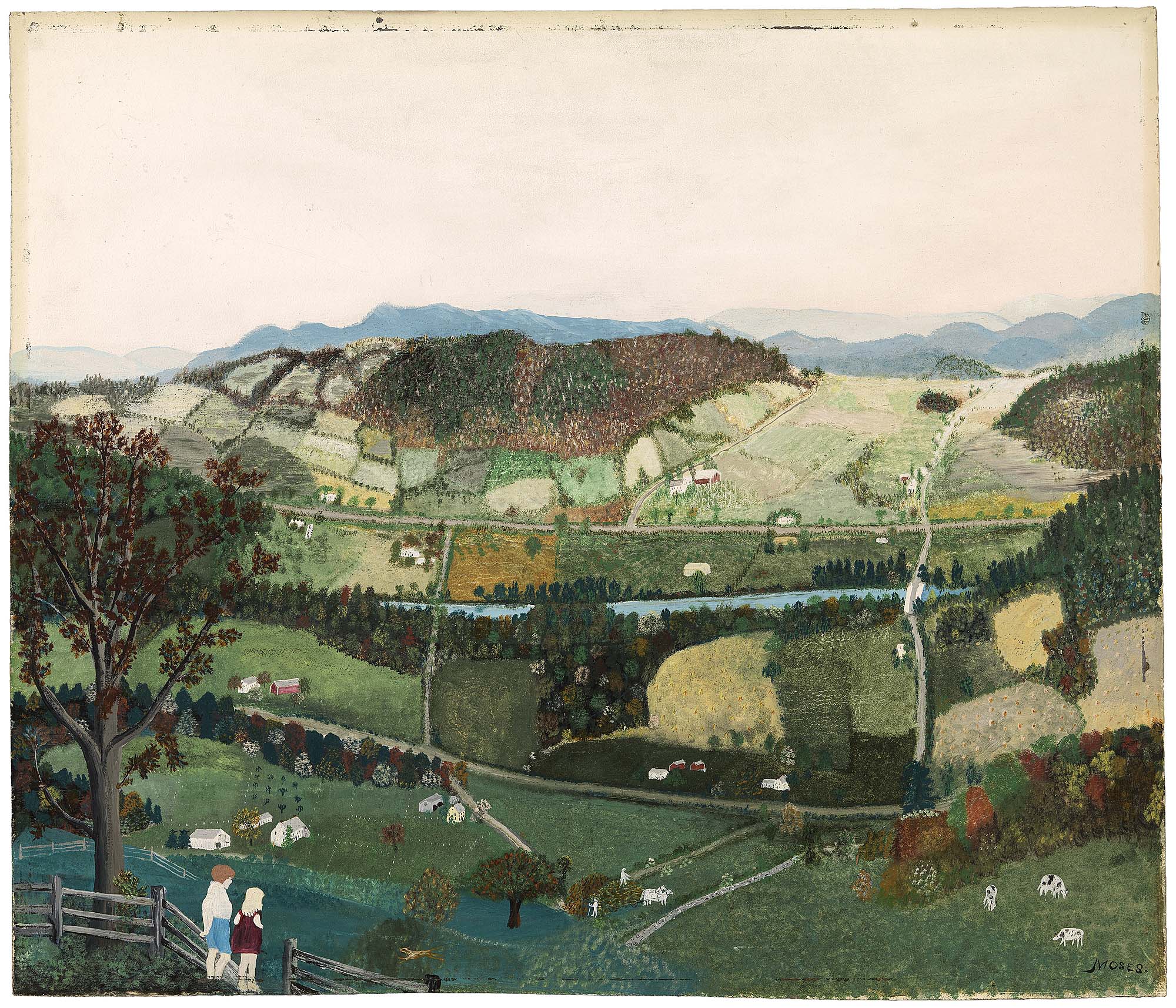

It was during her investigation for this section, titled “In the South” — in which she focused on the 18 years Anna Mary and Thomas Salmon Moses lived in Augusta County, Va. — that presented the greatest revelations to Umberger.

“The research into the five Virginia farms that Moses and her family lived on in the last decades of the Nineteenth Century made her come alive as an adopted southerner — in addition to being a native northerner. She loved the Shenandoah Valley deeply and returned to New York only reluctantly.”

Moses painted approximately 40 paintings recalling life in Virginia; these, the exhibition notes, “align with a Northerner’s view of a war recovery effort — showing communal efforts and favorable outcomes, and using positivity as a tool for overcoming memories that were not always so bright.”

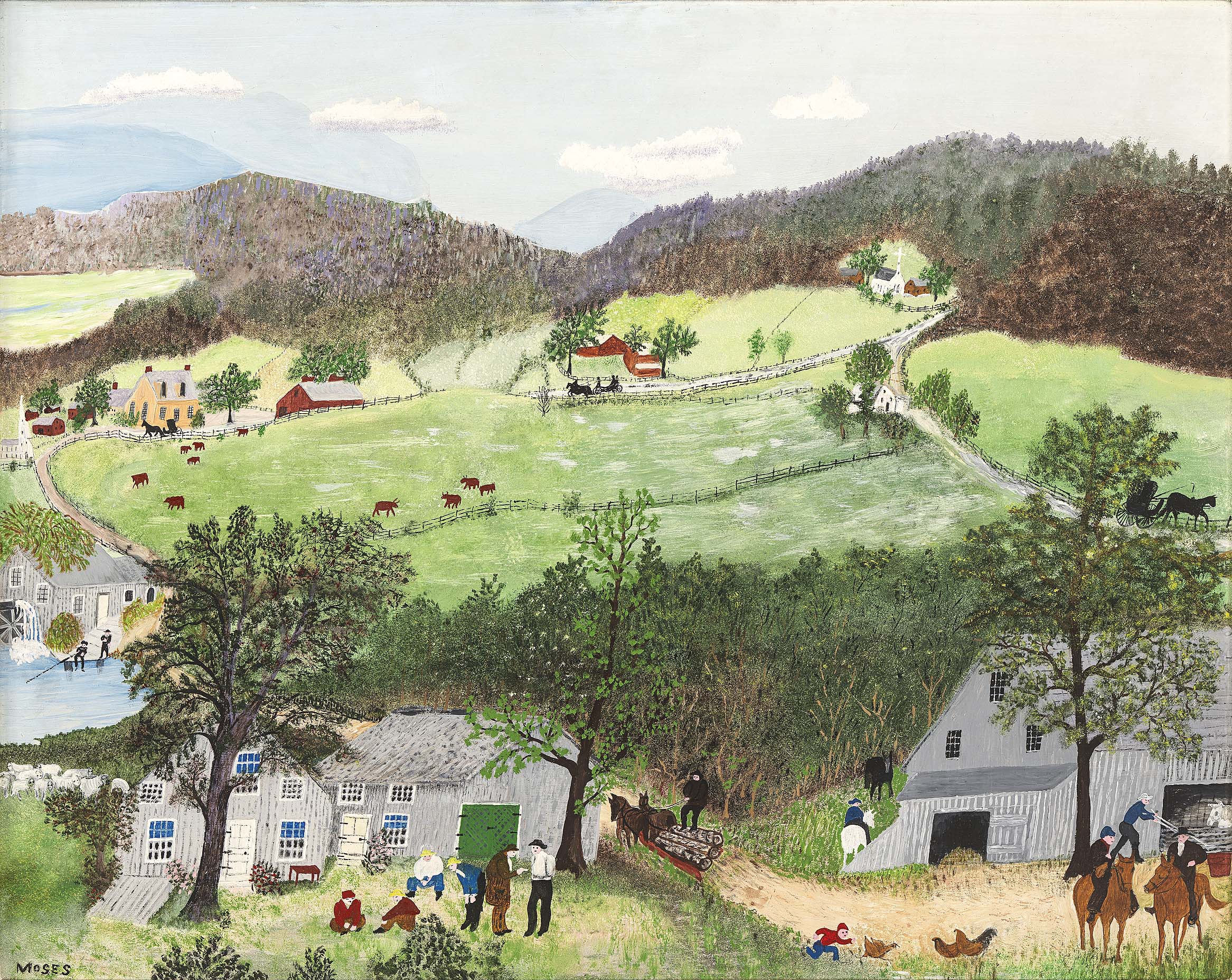

In “Apple Butter Making,” she depicted a late-summer Shenandoah Valley activity while “Moving Day on the Farm” reflected the hustle and bustle of the Moses family’s return to upstate New York, in 1905.

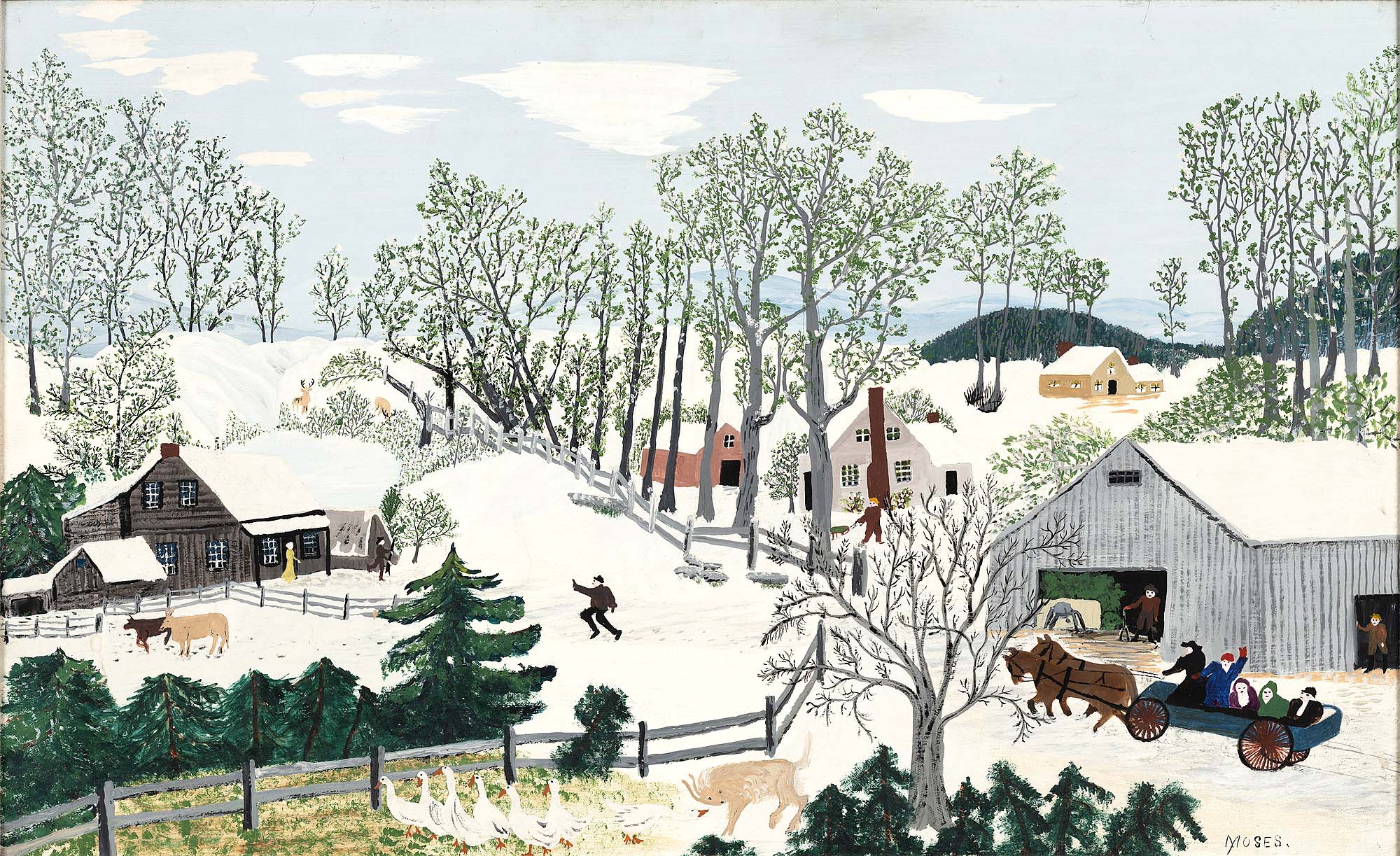

“Bringing in the Maple Sugar” by Grandma Moses, 1940 or earlier, oil on high-density fiberboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2024.37.3. © Grandma Moses Properties Co., N.Y.

Her artistic practice — and subsequent rise to art-world stardom — is thoroughly plumbed in “How Do I Paint?” Here, “Black Horses” recounts a moment in the artist’s family history, when her great-grandfather Archibald Robertson rode to warn neighbors about the oncoming British soldiers.

A scene from her own life is witnessed in “Grandma Moses Goes to the Big City,” in which she is shown, literally “at the crossroads of farm and fame.”

“Celebrations and Celebrity” dives into that fame; among those popular works featured there is “Out for Christmas Trees,” which was turned into a Hallmark holiday card in 1951. Another favorite holiday-themed painting — “Halloween” — was a rarely-captured scene additionally noted for taking place at night.

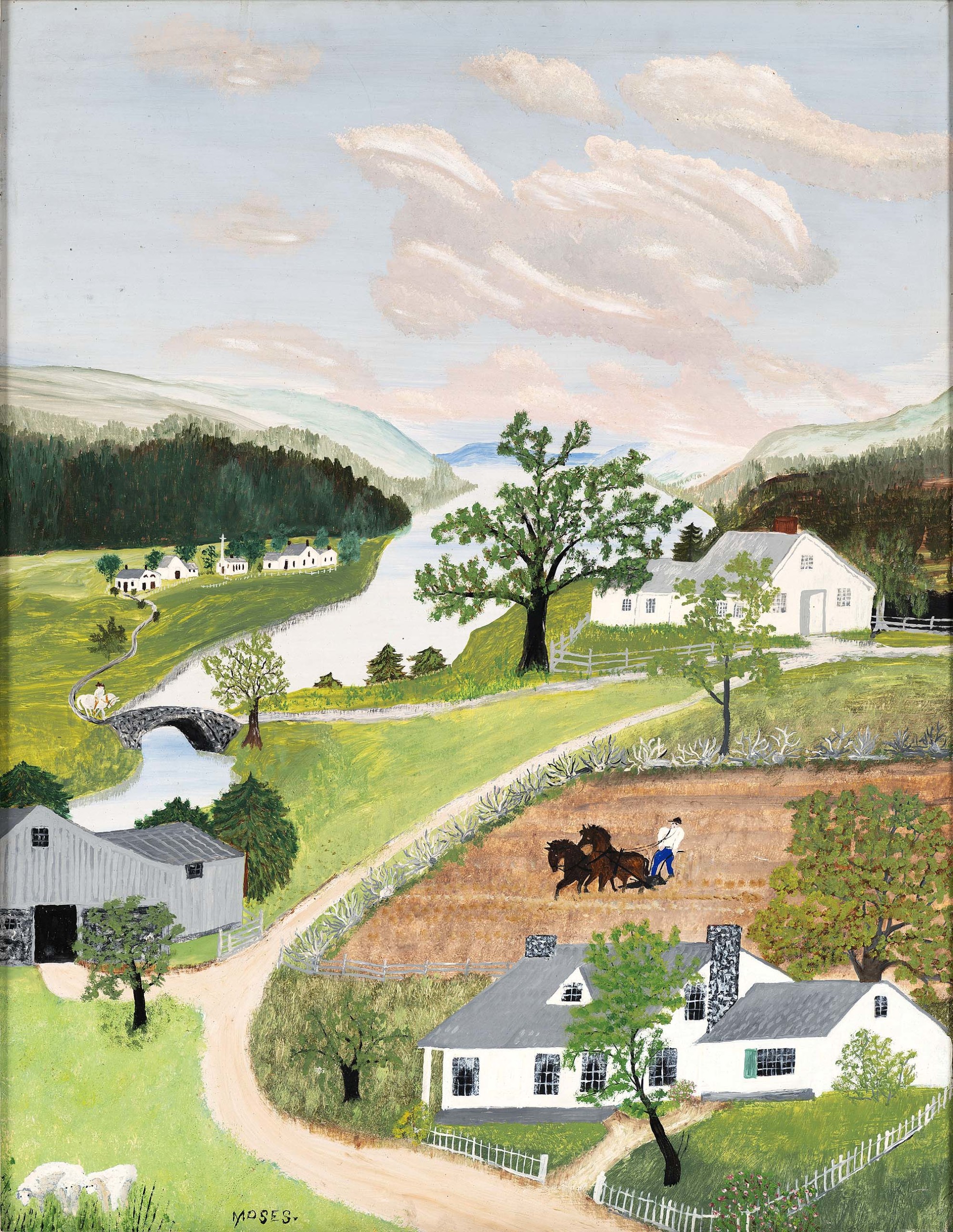

Continuing with “Memory is a Painter,” a section that celebrates Moses’ ability “to tap into the energy and emotion of a scene and convey a sense of seasonal transformation was perhaps her greatest strength as a painter.” Viewers will see “Early Springtime on the Farm,” “The Spring in Evening” and “We Are Resting.”

“We Are Resting” by Grandma Moses, 1951, oil on high-density fiberboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Kallir Family, in Memory of Hildegard Bachert, 2019.55. © Grandma Moses Properties Co., N.Y.

Moses once said, “I look back on my life like a good day’s work, it was done and I feel satisfied with it. I was happy and contented, I knew nothing better and made the best of what life offered.” Not only does this quote provide the subtitle for the exhibition but it closes the show in the section, “A Good Day’s Work” Among those selected for this section are her last completed work, “The Rainbow,” as well as “A Beautiful World” and “December.”

Griffey shared a general hope that visitors to the exhibition would “set aside labels like ‘self-taught’ and consider Moses as an artist who followed her own set of goals and ideas, and in so doing, made a highly original body of work. As the exhibition’s subtitle suggests, we want to emphasize that Moses’s concept of artmaking was a generative interplay of creativity and labor. But in the end, we hope that visitors simply enjoy themselves and become somewhat lost in the interesting story of her life and the visual pleasures of her imagery, maybe encountering some surprises along the way.”

“Grandma Moses: A Good Day’s Work” is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through July 12.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum is at Eighth and G Streets, Northwest. For information, 202-633-7970 or americanart.si.edu.