The Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum is housed in a 1930 residence created by architect John Gaw Meem to accommodate the director of the nearby Laboratory of Anthropology, founded in 1927 by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

By Laura Beach

SANTA FE, N.M. — Anyone visiting northern New Mexico during Easter Week may witness a phenomenon without precise parallel in the United States: religious pilgrims trudging north along US Route 84 toward El Sanctuario de Chimayo, 28 miles from the state capital.

The tradition might not have survived its Nineteenth Century origins had it not been for a foresighted group of preservationists, all members of the nascent Spanish Colonial Arts Society (SCAS), which saved the shrine in 1929 and subsequently built a foremost collection, roughly 4,000 works in all, emphasizing Spanish New Mexican art and artifacts, colonial to contemporary. In honor of its centennial, SCAS is presenting “100 Years of Collecting, 100 Years of Connecting,” organized by museum director and E. Boyd curator, Jana Gottshalk, and on view at the SCAS-run Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum through December 13.

Amid the recent rush to diversify collections of American art, we may overlook the broad fascination Spanish Colonial art held for early Twentieth Century designers, collectors and curators. Though other members of Santa Fe’s humming intellectual community were involved in SCAS’s founding, its genesis is closely associated with two prominent individuals — the artist Frank Applegate (1881-1931) and his frequent sidekick, author Mary Austin (1868-1934), who wrote about Spanish Colonial furnishings in New Mexico for The Magazine ANTIQUES in 1933. Also instrumental was Santa Fe architect John Gaw Meem (1894-1983), who popularized the Spanish-Pueblo Revival, an architectural style closely associated with Santa Fe and, loosely, the Southwest.

Left, decorated boxes in various media. Right, “La Virgen de la Luz” by Miguel Mateo Maldonado y Cabrera (1695-1768), Mexico, circa 1750. The painting is thought to have hung on the altar in a military chapel constructed on Santa Fe’s Plaza in 1761. Photo: Eric Cousineau.

Applegate and Austin were deeply committed to the perpetuation of local crafts traditions, spearheading two SCAS initiatives, Traditional Spanish Market, launched in 1926 and ongoing today (now administered by the Atrisco Heritage Foundation, this year’s market and related events are planned for July 25-27, with a Society celebration on Saturday, July 26) and the Spanish Arts Shop, which opened in Santa Fe’s Sena Plaza in 1930. With the deaths of Applegate and Austin, SCAS lost momentum, its collections mostly stored, managed and displayed by the Museum of New Mexico before the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art opened on Santa Fe’s Museum Hill in 2002. Seeking to emphasize its unique focus, the institution last year changed its name to the Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum.

SCAS had two great mid-Twentieth Century champions, Elizabeth Boyd White (1903-1974), known professionally as E. Boyd, and her assistant and successor, Alan Vedder (1912-1989). SCAS’s second curator, Boyd contributed Spanish Colonial watercolors to the Index of American Design, the Federal Art Project survey conducted between 1935-42.

When Donna Pierce, later curator of Spanish Colonial art at the Denver Art Museum, took up her post as SCAS curator in 1990, she marveled at the sturdy foundation left by her predecessors. “E. Boyd was the first scholar to place the SCAS collections within the context of the greater Spanish Catholic world while also viewing them as expressions of daily life in New Mexico. Her original typed records are a delight to read, excellent and extensive in detail,” Pierce observes.

This altar screen by Jose Rafael Aragón was SCAS’s first acquisition in 1928. Llano Quemado, N.M., circa 1840, wood, gesso, water-based paint. Photo: Eric Cousineau.

Pierce recorded interviews with Vedder and his wife, Ann, who together provided invaluable insight into the provenance and conservation history of the collection. With collaborators, the curator reviewed and photographed every object SCAS owned. The team’s work culminated in the two-volume set Spanish New Mexico: The Spanish Colonial Arts Society Collection, edited by Pierce and Marta Weigle and published by the Museum of New Mexico Press in 1996.

“Ann Vedder called it our museum on paper,” says Pierce, who subsequently contributed to Conexiones: Connections in Spanish Colonial Art, edited by noted New Mexican writer Carmella Padilla and released in 2002 to coincide with the opening of the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art. Pierce and others are preparing a history of SCAS, to be released in December as the centennial concludes.

Since its first acquisition in 1928, the Society’s collection has grown to include New Mexican art and artifacts crafted over five centuries, plus related objects, most from the broader Latin world. Devotional pieces — among them paintings, many on wood panels, called retablos and carved and painted figures called bultos — join textiles, costumes, metalwork, furniture, pottery, straw-appliqued objects, tools, weapons and horse gear.

“This is the only institution that since 1925 has consistently collected Hispano New Mexican art. We’re very proud of that,” says Jennifer Berkley, the Society’s executive director. Noting that work by Traditional Spanish Market exhibitors accounts for half of SCAS holdings, Berkley observes, “Our collections serve as inspiration for artists today, whose own work we hope will inspire future makers.”

Much of SCAS’s collection of roughly 4,000 objects consists of pieces made by exhibitors at the annual Traditional Spanish Market, launched by the Society in 1926. Photo: Tira Howard.

Featuring nearly 200 objects and representing over 120 historic and contemporary artists, “100 Years of Collecting, 100 Years of Connecting” snakes through the rooms and corridors of the museum, housed in a 1930 residence John Gaw Meem created for the director of the Laboratory of Anthropology, whose patrons included John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Enchantingly, the original’s intimate character and handsome architectural details are little changed.

The show opens with drawings submitted by Meem as part of his winning proposal, then turns quickly to SCAS’s first major acquisitions. Newly returned to the Society from Santa Fe’s Palace of the Governors, where it had been on loan for nearly a century, is the undisputed masterpiece of the SCAS collection and its first purchase: a more than seven-and-a-half-feet wide altar screen from Llano Quemado, N.M., painted in water-based paint over gesso on wood around 1840 by santero José Rafael Aragón (1795-1862), who depicted the Virgin Mary and saints.

Austin wrote that Applegate, curio dealers in hot pursuit, acquired the treasure for the Society for $500.

A panel in the same gallery describes SCAS’s second acquisition, the Sanctuario de Chimayo. As Austin later recalled, “I was away at the time, lecturing at Yale University, but Frank wrote me promptly, and I was able to find a Catholic benefactor who made possible the purchase of the building and its content, to be held in trust by the Church for worship and as a religious museum, intact, and no alterations to be made in it without our consent.”

Dollhouse-sized miniatures by Katherine Sydoriak fill nichos. Photo: Laura Beach.

Punctuated by a nicho housing dollhouse-scale miniatures by Katherine Sydoriak, a narrow hall leads to a second gallery where some of SCAS’s earliest treasures are arrayed. Instructive in their variety, decorated boxes and chests in wood and leather — some carved and painted, others lacquered and most made or found in New Spain — ornament one wall. Opposite, housed in a provincial Baroque frame is a large portrait on panel depicting San Rafael, painted by New Mexico’s earliest identified santero, Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, and dated 1780.

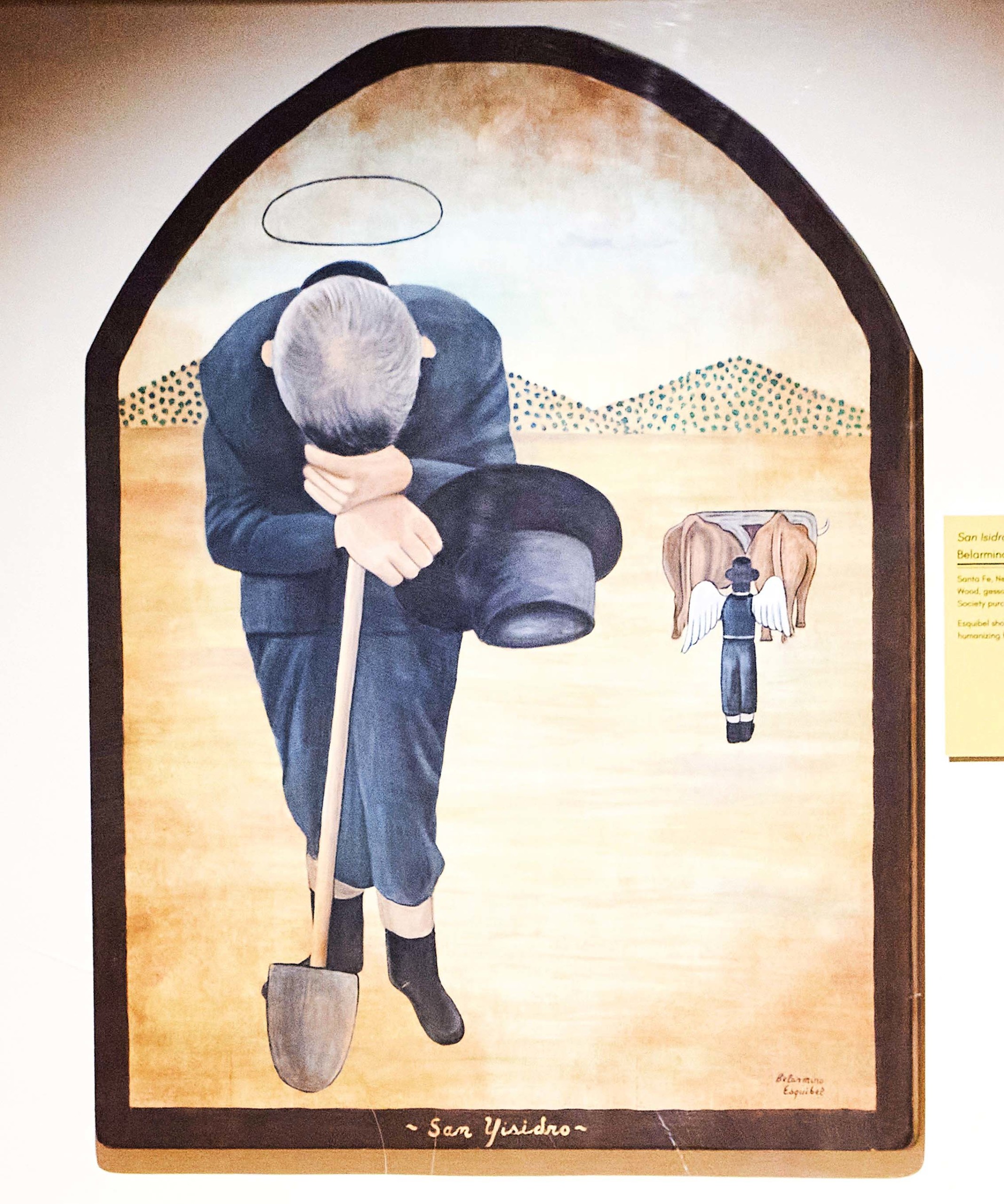

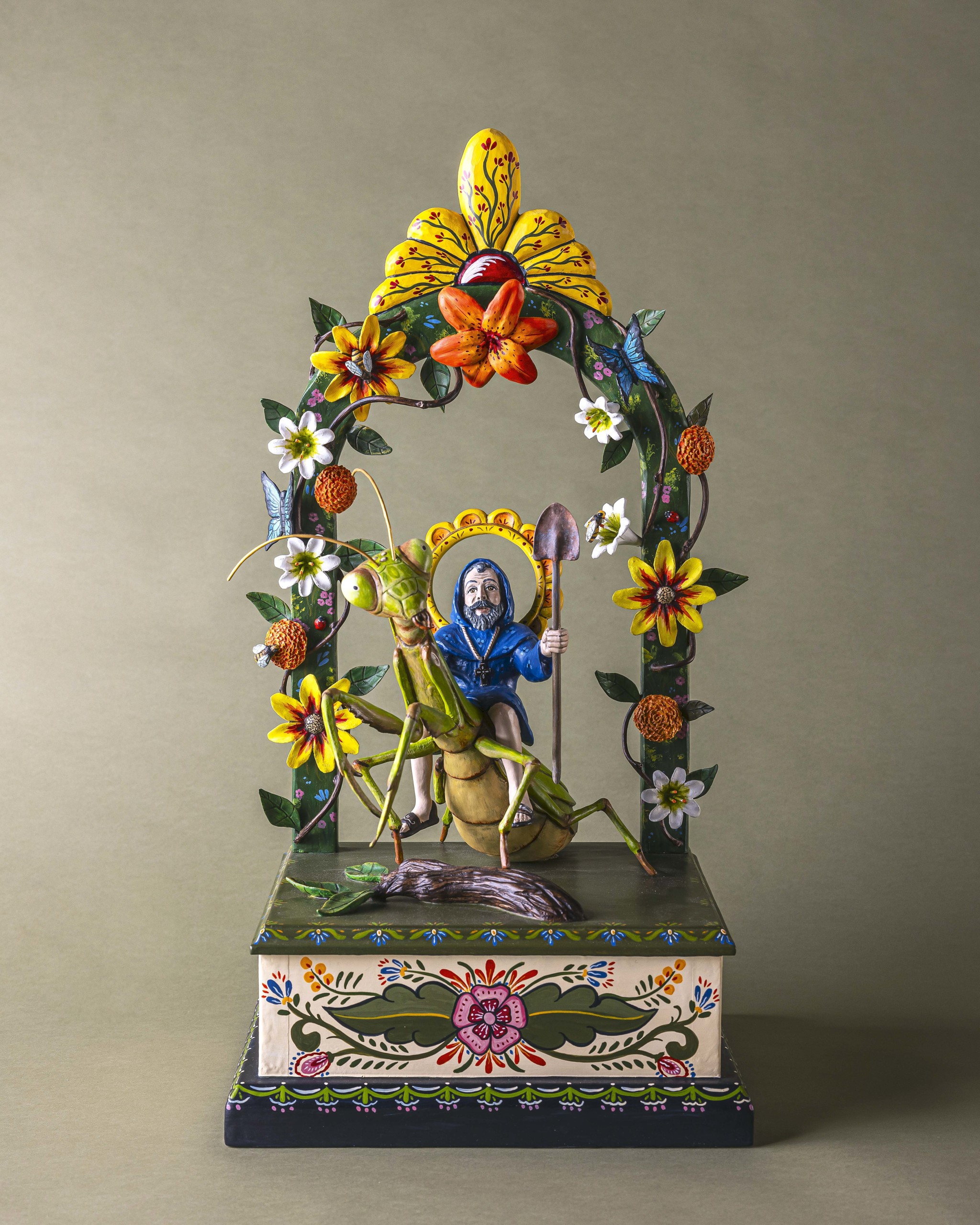

A third gallery showcases gifts from SCAS benefactors. From Meem and his wife, Faith, founding members of the Society, come distinctive Rio Grande blankets and a late Eighteenth or early Nineteenth Century bulto of San Isidro Labrador by an unknown santero from Socorro, N.M. Fashioned as a humble everyman, the patron saint of farmers plows his fields, angels at his side.

Once married to photographer Paul Strand, artist Rebecca Salsbury James (1891-1968) is here remembered for her 1960-61 wool-on-linen embroidery, worked in New Mexico’s traditional colcha stitch, of the Santo Nino de Atocha, plumed hat on his head and staff and flowers in hand.

From Margretta Dietrich (1881-1961), a Society founder who moved to Santa Fe in 1927 and advocated for Native American rights, comes a chip-carved child’s highchair made in 1924 by renowned carver and furniture maker Jose Delores Lopez (1868-1937) of Cordova, N.M., for his great-grandson Fidel.

Child’s chair by Jose Delores Lopez, Cordova, N.M., 1924, wood, nails. Bequest of Margretta S. Dietrich. Photo: Laura Beach.

Subsequent galleries feature more recent work by SCAS-affiliated artists. There is the imposing “Monja Coronada,” or crowned nun, bulto by Joseph Asencion Lopez, who traveled to Morelia, Mexico in 2000 on a Society grant to study traditional sculptural methods.

Much contemporary Hispano devotional art is enlivened by humor and social commentary. Gustavo Victor Goler of Taos is represented by the 2016 “Cruising Heaven,” a carved and painted sculpture depicting the Holy family promenading the heavens in their customized lowrider convertible. In “The Folk Art Collectors,” another master carver, Luis Tapia of Santa Fe, spoofs traditional art as tourist commodity.

Neatly closing the collecting loop that began in 1929 with its purchase of the Sanctuario de Chimayo, SCAS ends the show with its most recent acquisition, “Nuestra Senora de Tsa-mayo/Chimayo” of 2024. The three-dimensional retablo by Vicente Telles, an Albuquerque-based santero and Traditional Spanish Market artist, tells a more nuanced version of the Chimayo story, one acknowledging the sanctity of the setting for native Tewa people, who predated Spanish settlers.

“Every museum needs to refine its collections,” says Pierce, acknowledging some recent light housekeeping. The Society is offering as gifts duplicate Puerto Rico santos from its collection to the Museum of International Folk Art, where it currently has several pieces on loan, and in June formalized its gift of architectural artifacts to El Rancho de Las Golandrinas, the living history museum south of town.

From youth arts exhibits to a lowrider bike club and colcha embroidery lessons, the Society’s engagement with its community is deep and ongoing. As Berkley says, “We have people actively engaged today whose families were part of the Society’s founding. It adds to the warmth of the organization and sets us apart.”

The Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum is located at 750 Camino Lejo in Santa Fe. For information, www.nmheritagearts.org.