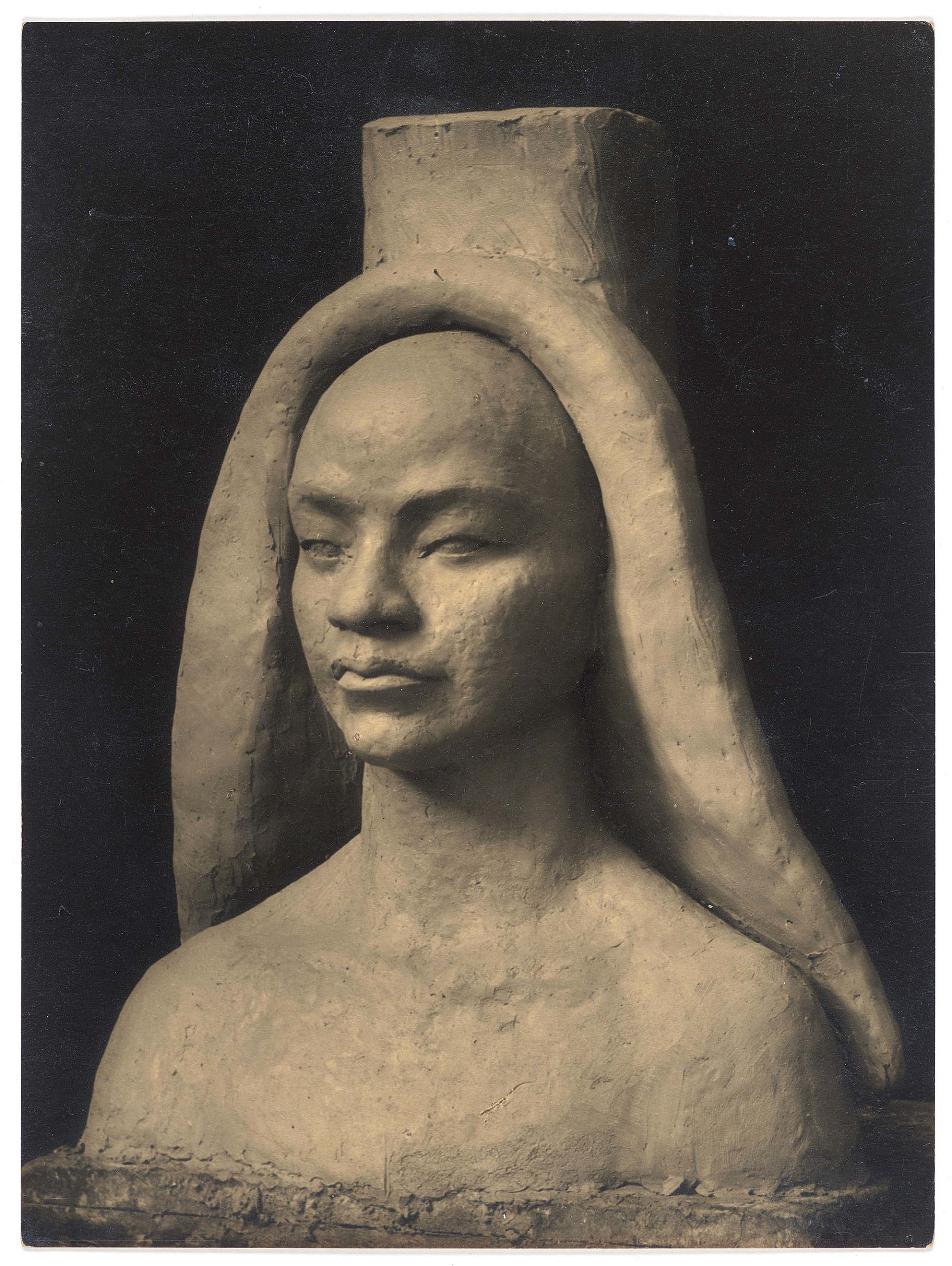

“Congolais” by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, 1931. Purchase 32.83. Whitney Museum of American Art/New York, NY/USA. Digital image ©Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NYC.

By Kristin Nord

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Brilliance, beauty and magisterial sculpture helped define Nancy Elizabeth Prophet’s work. In many ways, these qualities shone brightly in her carefully choreographed photographic self-portraits.

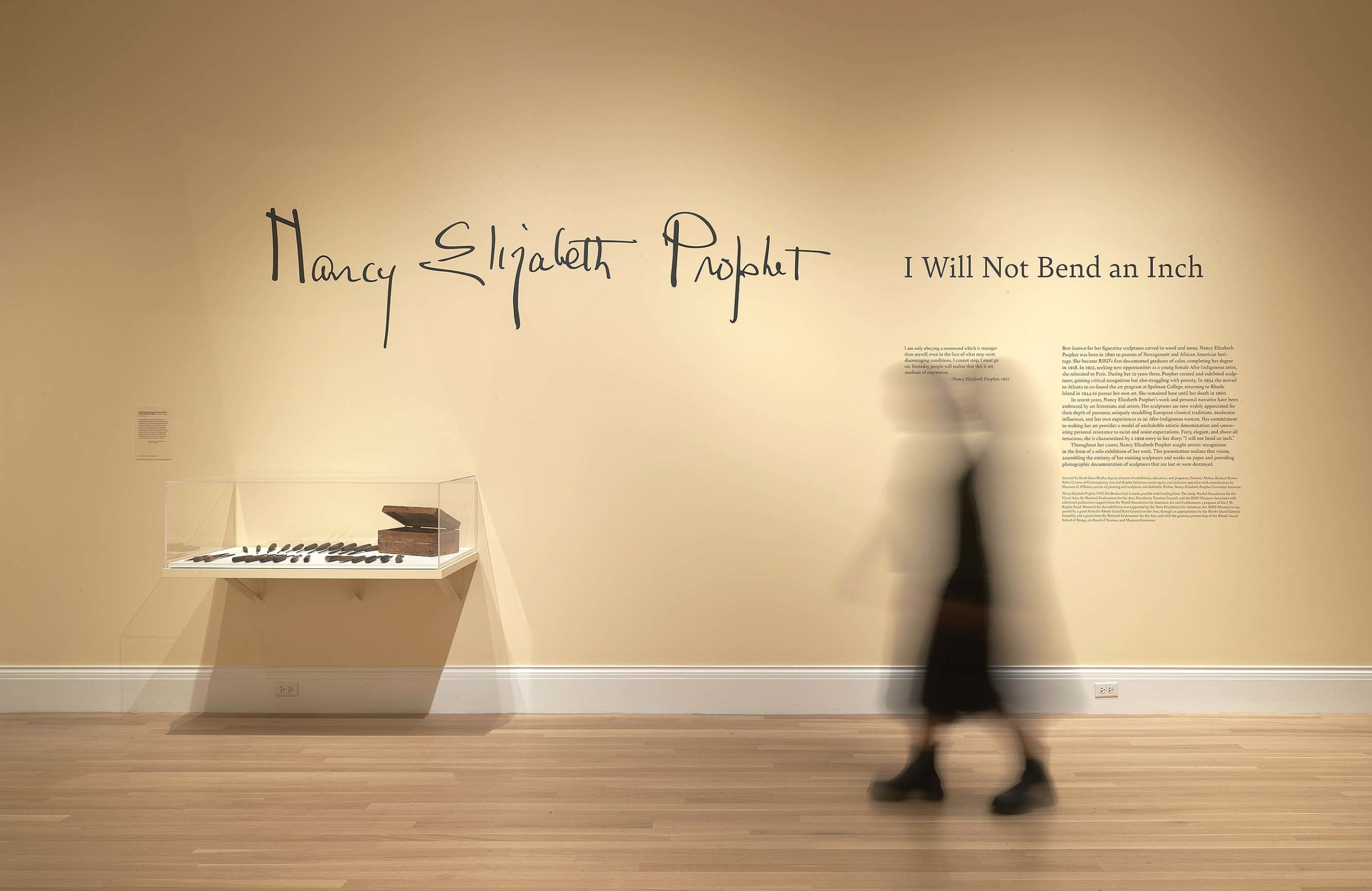

In the exhibition “I Will Not Bend an Inch,” running at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum through August 4, Prophet has finally been given the solo show she yearned for nearly a century ago. One can’t help but encounter these works with awe for what she achieved against all odds as well as sadness at what might have been.

Prophet was born in 1890 in Warwick, R.I., to parents of Narragansett and African American heritage. She was RISD’s first documented graduating woman of color, earning a degree in freehand drawing, painting and portraiture in 1918.

Rhode Island had played a historic role in the slave trade, and, in the early Twentieth Century, discrimination was still a common occurrence. Her parents had worked as domestics for a wealthy family in Providence. Perhaps in part, as if to eschew her identity, she would change the spelling of her surname and refer to herself alternately as Elizabeth or Eli rather than Nancy. In the census rolls, she identified as mixed race in 1910, Indigenous in 1920 and Black in 1950. When it became clear she could not succeed as an artist in the early years of her career in New York City, she left for Paris to pursue studies in sculpture. In many ways this was not an easy decision and she battled poverty throughout much of the rest of her life.

Installation view of “Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend An Inch” on view through July 28 at the RISD Museum.

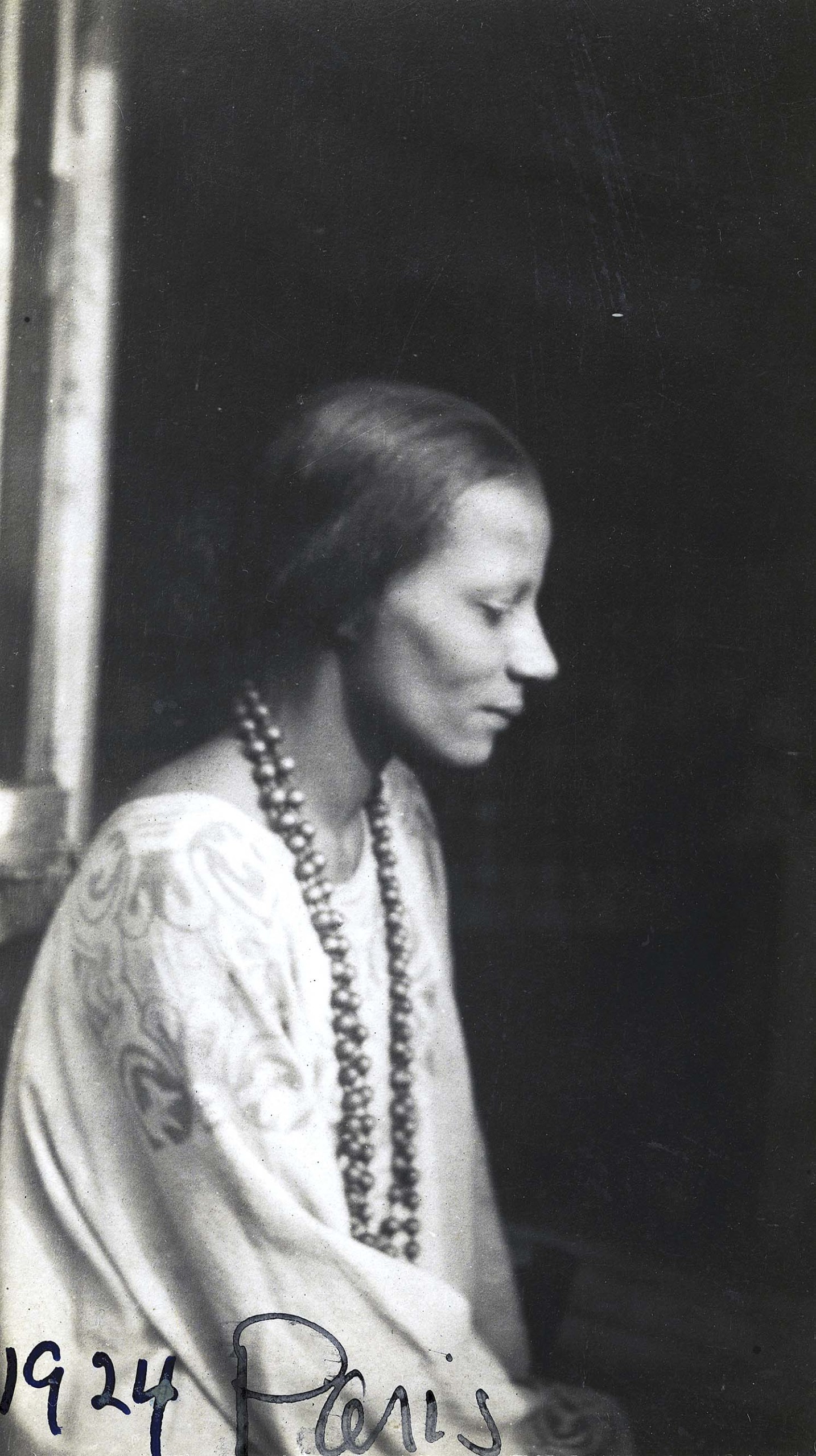

Yet, to the world, she presented herself as an artist of regal bearing, beauty and style. And she was indeed a great beauty, often photographed in flowing capes, stylish hats and baronial necklaces, distinctive for her high cheekbones and her oversized, tapered hands. She would take equal care in the presentation of her art: hiring Bernes, Marouleau & Cie, the photographers who would also document the work of Rodin and Picasso, to prepare what now looms in part as a ghostly assemblage of her oeuvre. Given the size and weight of sculptures made of marble, bronze, wood and plaster, Prophet knew that photographic representation would be crucial if her work could be presented outside the studio.

Sarah Ganz Blythe, RISD’s deputy director of exhibitions, education and program, reported that in Paris, she met a “highly evolved and relatively open” network of artists, teachers, studios and exhibitions. “This, in turn, afforded her a pathway by which to earn recognition and distinguish her work in the United States. While studying in Paris was seen as a rite of passage, her decision to enroll in the women’s class at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, overseen by Victor Joseph Jean Ambroise Segoffin, was still a fairly radical act.” Segoffin became, in essence, her calling card and she invoked his name long after he had died.

Her “things,” as Prophet called her sculpted objects, projected visages with an outer serenity and inner tension; they tended to serve as vessels of emotional states more than as likenesses. She kept a 46-page diary during these years abroad and it chronicles her ideas as well as her financial struggles.

“Prophet in Paris,” 1924. Nancy Elizabeth Prophet Collection, MSS-0028, Special Collections, James P. Adams Library, Rhode Island College.

W.E.B. DuBois had connected her to the Black artistic community in Paris and he and his son-in-law, the poet Countee Cullen, were two of her most fervent advocates. Both championed her in profiles in the leading New Negro publications of the day and the artist Henry Ossawa Tanner recommended her for a prestigious Harmon Foundation Award, which she won in 1928. She exhibited at Salon d’Automne, the Societe des Artists Français and with the Boston Society of Independent Artists. But her financial situation remained tenuous and, ultimately, she was forced to return to America. By 1934, she accepted a job underwritten by the Carnegie Corporation to establish the art program at Spelman College in Atlanta. A decade later, when she left Spelman and sought to resurrect her studio practice back in Providence, her opportunities had dried up.

Contemporary artist Simone Leigh, whose video opens the show and responds to Prophet’s challenges and the historical lack of access for Black women artists, considers Prophet a talisman of sorts who has spoken to her through time. In Leigh’s essay, “I Was Hungry, but This Seemed of Little Importance,” which appears in the exhibition’s accompanying catalog, she addresses the extreme sacrifices the artist made for her art. Prophet kept up appearances as she struggled to put food on the table — and reported ruefully in one diary entry of having gone without eating for so long that on one occasion she had lifted the scraps off a dog’s plate.

“She took her work so seriously, even being hospitalized for starvation and then climbing out of that hospital bed right back into the studio,” Leigh writes. “Recently it has made me think about Hilma of Klint, who seemed to foresee that the world may not be ready for her work but eventually will be.”

“Walk Among the Lilies” by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, circa. 1931-32. Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

Revisiting the early part of the Twentieth Century, the Narragansett historian Mack H. Scott III reminds us America was far from offering a beacon of opportunity for women artists of color. “That she moved to France speaks volumes about the racial and social climate of America in the 1920s and 1930s. The reality is that Prophet could not make it as an artist in the United States,” he said.

In the end many of her works were destroyed or lost — but the two dozen that remain make for a haunting presence. Those who visit the show can’t help but respond to her sculpting skills, or her objects’ emotional content.

Consider the work, “Silence,” suggested by Dominic Molon, RISD’s interim chief curator and the Richard Brown Baker curator of contemporary art for its masterful distillation of the principles inherent in Roman Greco art and its streamlined and neutral features and indistinct edges. The bust, believed to be a self-portrait, “continues to challenge the viewer today just as it must have in the 1920s,” he said.

The impact of her work in the main gallery is palpable, as one moves from “Head of a Negro” (circa 1924) to “Silence” (circa 1926), “Discontent” (circa 1929), “Youth” (circa 1930) and “Congolais” (1931). “Head of a Negro” has been carved in maple, the art historian Horace D. Ballard, the Theodore E. Stebbins Jr, curator of Art at the Harvard Art Museums, has written, perhaps for these reasons: it enabled Prophet to work (relatively) quickly and to control the fracture (surface) and coloration. Her aesthetic choices result in a masterful confluence of the representational politics of the New Negro Movement, beaux arts academic traditions and the refined folk tenets of the Arts and Crafts Movement, he added.

“Head of a Negro (also referred to as Head in Wood)” by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, circa 1924. Gift of Miss Eleanor B. Green. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

Stephanie Sparling Williams, the Andrew W. Mellon curator of American Art at the Brooklyn Museum, said “Youth (Head in Wood),” is notable “for its balance between grit and grace, tenacity and surrender, aggression and sensitivity,” and Prophet’s attention to detail. In this work and others, one sees the artist has elected to leave the base of the work unfinished. One can’t help but think of the art that has burst forth from raw materials.

“Congalais,” a bust rendered in cherry wood was inspired by a visit to the Exposition Coloniale Internationale, which opened in Paris in 1931 and ran for six months, drawing 33 million visitors. Prophet had been particularly drawn to the sculptural busts from Africa. She summarized their impact in a letter to DuBois, “Heads of thought and reflection types of great beauty and dignity of carriage. I believe it is the first time that this type of African has been brought to the attention of the world of modern times. Am I right? People are seeing the aristocracy of Africa.” Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was so taken with this work when it was exhibited in 1932 in Newport, that she purchased it for the then-recently founded Whitney Museum of American Art.

“Silence” by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, 1920s. Gift of Miss Ellen D. Sharpe. RISD Museum, Providence, R.I.

For someone whose “Head of Ebony” (1926-29, altered later) had been stationed on DuBois’ desk at Atlanta University for so many years, the last years of her life were grim indeed. She spent four of them in the Rhode Island State Hospital for Mental Diseases and ended her life as a domestic for a wealthy family in Providence’s East Side. She had left her tool kit with its hand-carved gouges and chisels at Spelman and it had taken three years of correspondence with the university president to have them retrieved. There are so many questions about her life and work that are unanswered and perhaps unanswerable. But her art speaks to us — and would have us think and listen.

“I think Prophet is a case study in survival and authenticity,” Mack said. “Born into a society that denied her ingenuity and attempted to circumscribe her ambitions, her life and work stand as a tribute not only to her indomitable character but also to the obstinacy of her ancestors who refused to be erased. It was this irrepressible spirit that she encapsulated in wood and stone.”

The Rhode Island School of Design Museum is at 20 North Main Street. For more information, www.risdmuseum.org or 401-454-6500.