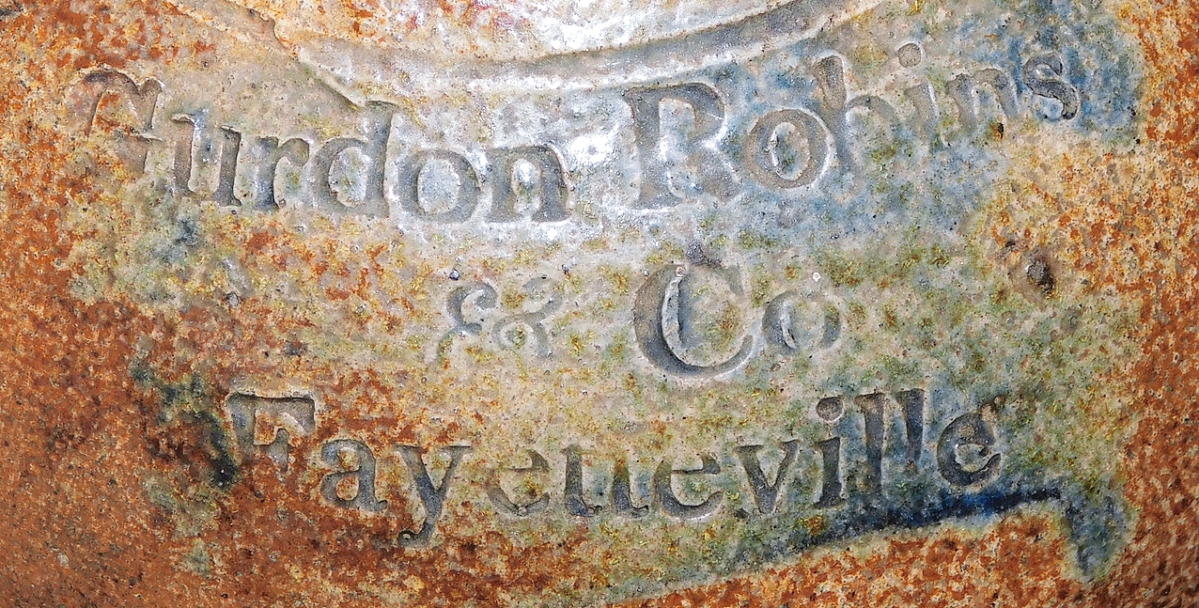

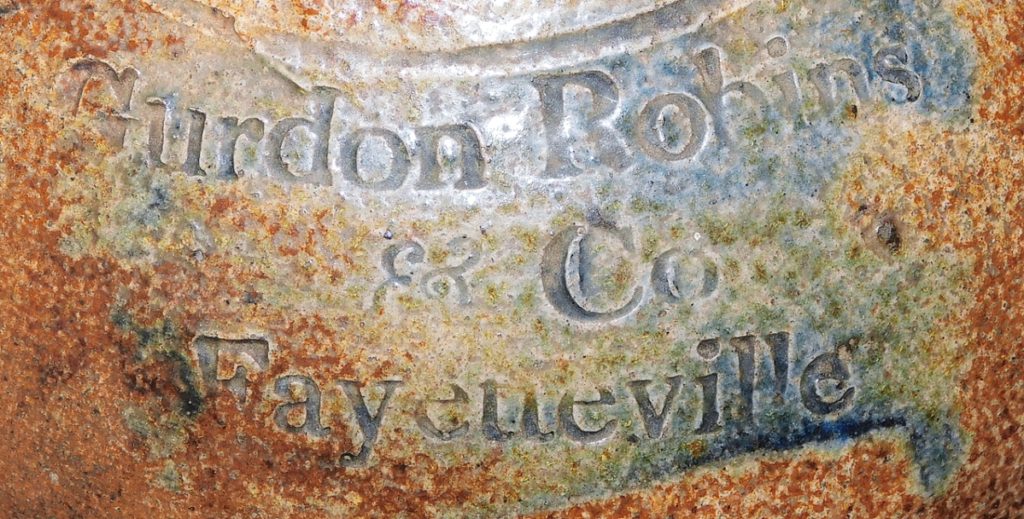

Although falling short of the catalog estimates of $15/25,000, this one-handle salt glaze jug is an extremely rare early stoneware example from the Gurdon Robins & Co, Fayetteville, N.C. This pottery only operated from 1819 through 1823. It was an $11,000 bargain to a discerning collector.

Review by Marty Steiner, Photos Courtesy Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society

BENNETT, N.C. – Resurrection and revival are generally thought of as religious terms. The arts world seems to prefer the term renaissance. When it comes to folk arts, including folk pottery and its history, the faith-based terms may be more appropriate. Allen Eaton’s 1937 book Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands may be the Book of Genesis for today’s renewal of interest and production of folk pottery. A single photograph of Lanier Meaders sparked interest in the pottery forms that had been and continued to be made by traditional methods handed down through family generations.

In 1980, the Smithsonian Institute’s Folklife Center published its very first folklife monograph, the Meaders Family, North Georgia Potters. The Meaders family had been producing pottery in North Georgia since around 1820. The monograph stirred the interest of a number of collectors, museums and antiques dealers. Among these was Roy Thompson, an antiques dealer in Glastonbury, Conn., who started buying hundreds of examples of Southern pottery.

In 1990, Thompson established the Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society. The March 16, 1990 Antiques and The Arts Weekly cover article by Thompson brought the “Vernacular Southern Folk Pottery” to a national collecting audience. The society issued its first newsletter in fall of 1990. The winter 1991 reflected, “In the few months that have passed since our premier newsletter, we have received an incredible number of responses from across the country. We never expected such a deluge!” Thompson, the only dealer at the New York Antiques Show in January 1991 to offer Southern folk pottery, sold about 500 examples.

Glazes and their application can transform ordinary forms into works of art. This simple 1946 plate form by Water B. Stephen at the Nonconnah Psgah Forest Pottery literally glows with its blue and aqua crystalline glaze. It sold for $193.

Like the country church counterpart, Southern pottery kiln openings became the revival camp meetings for new pottery collectors. Conversion from onlooker to purchaser became the baptism of an entire generation of these new collectors. Among these were Foil and Polly McLaughlin. The society has continued to preach its gospel for more than 30 years with newsletters and absentee sale catalogs.

That same Winter 1991 newsletter introduced Billy Ray Hussey as a traditional potter. On March 1, 1994, Roy Thompson “passed the torch” to Billy Ray and Susan Hussey to head the society.

In addition to the study, gathering and making information available about Southern folk pottery, the society also had begun presenting well-documented absentee auctions of this pottery genre. The society’s most recent sale that eneded April 16 was the first part of the Foil and Polly McLaughlin couple’s lifetime collection from their estate. Their lifetime of collecting Southern folk pottery and the relationships that this collecting couple developed with the artist-potters was presented by the society in its Collectors Vision Series: Volume One catalog. These catalogs, spiral bound to stay open to any page, are collectible as a reference library.

The ultimate free-range chicken is this colorful 2004 Charles Moore pedestal rooster. It crowed up $3,070.

Pottery has been an essential component of the household for centuries around the world. This was especially true in the new United States. While the more civilized and affluent areas bought and used imported fine works, many primarily for decorative purposes, the frontier and rural backcountry needed their pottery for more practical purposes. As a result, many of the earliest American examples are utilitarian items. These basic forms and their glazes were designed to be durable and functional. The very fact that intact early examples still exist is a testament to these potter’s and glazer’s skills.

Many pottery auctions focus on specific periods and styles, such as the Arts and Crafts period or on rarities that command high prices, such as those of enslaved potter David Drake (1801-1865). Society auctions typically offer the full range of Southern examples from the earliest to current examples with a wide range of prices realized. The society’s catalogs fulfil its educational mission, providing both specific information about the listed items (dates, glazes and construction) as well as extensive research material and resources about the potters, relevant exhibits and other historical provenance. This sale catalog had a bibliography of 185 such sources. Listings are in alphabetical order by the state of the pottery source order with the Carolinas further listed by known pottery areas, such as the Catawba Valley, Buncombe Valley or the Piedmont in North Carolina

This sale of the McLaughlin couple’s lifetime collection reflected the full range of material. There were a number of early utilitarian examples among the 316 lots in the sale. These included some the highest priced lots. Daniel Seagle worked in the Catawba Valley area, today’s Lincolnton, in the 1840s-50s. His signed 10-gallon storage jar with unusually large lug handles came with important Seagle family documentation that supported the $6,050 price in this sale. Another signed Daniel Seagle example, a 5-gallon loop handled jug, reached $4,840. Son, James Franklin Seagle examples from post-Civil War included a signed 3-gallon jug at $990 and a 4-gallon storage jar at $303. Other 1850s Catawba examples included an extremely rare signed Isaac Lefevers 1850s 3-gallon jug at $14,300, the top dollar lot, and a Henry Ritchie 4-gallon storage jar for $3,300.

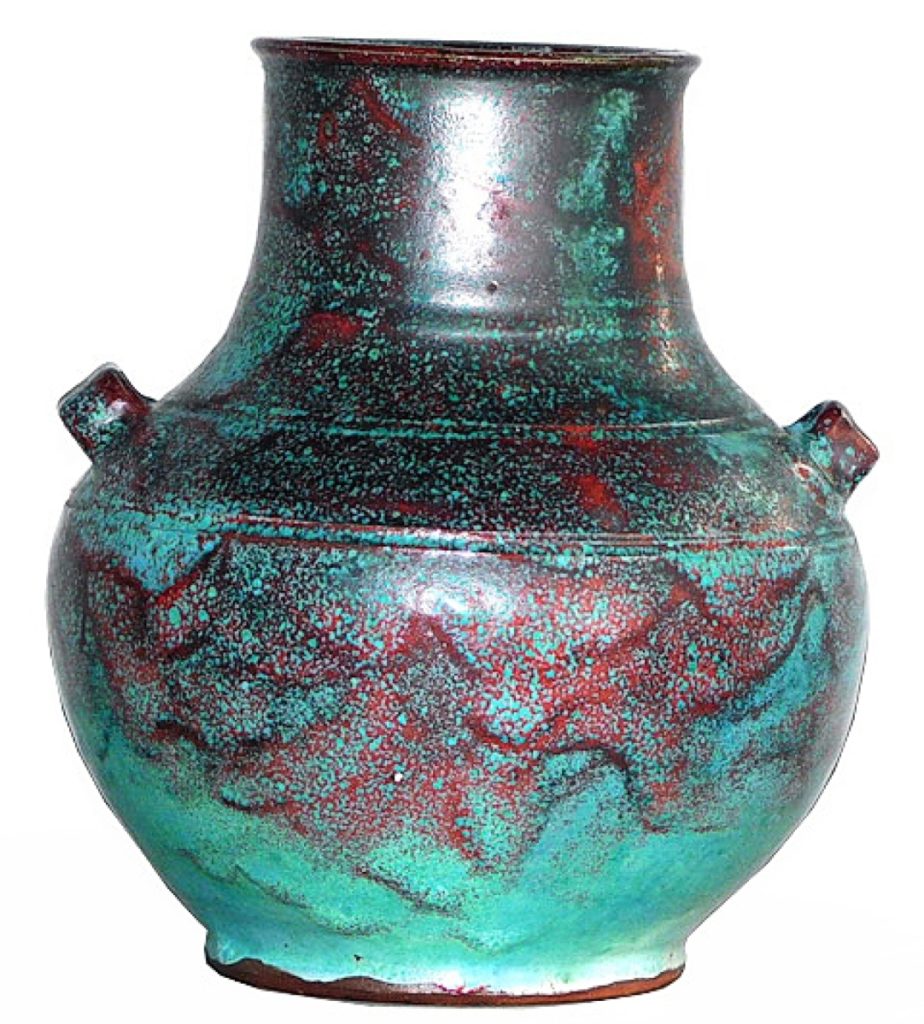

Seemingly at odds with the vast majority of Southern pottery, Ben Owens I regenerated Oriental forms as well as their Chinese glazes. This signed 1930s vase brought $4,400.

Swirlware is distinctive to the Catawba Valley area and involves the working together of two different color clays producing a barber pole, stripe-like vessel. The forms are much the same as all others, including jugs, pitchers, bowls and vases. This sale featured 19 lots of Burlon B. Craig’s swirlware creations with some unusual miniature forms, including jugs, monkey jugs and pitchers. Five Reinhardt Brothers of Vale, N.C., swirlware pieces from the 1930s were also sold.

The Piedmont area of North Carolina also produced early pottery, much drawing from a Germanic background of forms, techniques and salt glazes. Gurdon Robins & Co of Fayetteville only existed from 1819 to 1823. A rare, clearly marked single-handle gallon jug drew much attention and sold for $11,000. The capacity was indicated by a single inscribed line around the shoulder. Only three or four marked examples from this pottery are known to exist. Other salt glaze examples included the post-Civil War simple utilitarian forms by Enoch Craven, Jesse Jotdan, Moffitt and unsigned works were sold.

Georgia pottery from this collection included 21 lots of Meaders family works. Among these were ten Lanier pieces with three face jugs. At the time of the Smithsonian monograph, Quillian Lanier Meaders was producing practical wares with occasional face jugs. It was Lanier’s face jugs that have resonated with the collecting public after the Smithsonian monograph, and he became famous for them. This collecting couple’s focus was clearly on form and glaze rather than currently popular items. A Lanier devil face jug with glazed quartz rock teeth did draw a $3,740 winning bid, well over estimate.

A relatively early Lanier Meaders devil face jug. Glazed over quartz rock teeth, protruding lips, pointy ears and subdued horns scared up a strong $3,740 winning bid.

North Carolina’s Burlon B. Craig’s work also generated a variety of face forms with 17 examples sold from this collection. Forms included a covered canister, wall pocket, wig stand, pitchers and some oversized jugs. Strong sellers included a devil face jug at $3,080 and the wig stand at $1,595.

Another whimsical form practiced by many Southern potters was the pedestal rooster. Two signed Edwin Meaders examples drew $1,375 and $990 winning bids. Two particularly large and colorful roosters by Bill Flowers, North Carolina, sold for $770 each.

Although one of the defining elements of Southern pottery is the use of alkaline glaze, many potters worked with other types of glaze. Among these potters were the Ben Owens, who created Oriental forms with Chinese blue glazes. Examples in this collection and sale included three Ben Owen 1930s examples from the Busbee’s Jugtown Pottery. His Han dynasty-inspired double-handle vase drew $4,400, an angular rim bowl, $880 and an angular vase, $1,485.

A particularly unique form of cameo pottery that resembles Wedgwood included four lots from the Pisgah Pottery in Arden, N.C. Each piece is decorated with white-on-blue American prairie scenes, including oxen-drawn covered wagons, cabins and mounted riders. Created by Walter Stephen in the 1950s, a lidded teapot brought $248 and a wide bowl $165.

This scarce potter’s signature mark was impressed on the top of one of the unusually wide lug handles.

Art pottery forms, glazes and decoration, not particularly Southern by history or tradition, became part of the rejuvenated Southern potters’ product line. A number of transition pieces from the traditional Southern forms were included in this sale. Most drew modest bids and may well represent the future of collectible Southern pottery, especially to new collectors.

Although not pottery, the McLaughlins were also drawn to another Southern folk art form, the carved wood model. Six examples of mule-drawn wagons and a sled by Willard Watson were sold to a single buyer, keeping the entire group together. Models by Willard and traditional quilts by his wife, Ora, are in the Smithsonian’s folk art collection.

If a single word could explain collecting, that word would be “passion.” When that passion turns to serving the collecting community, the words commitment and dedication also come to mind. For their assistance in developing this feature, we are thankful to Billy Ray Hussey and the Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society, especially for its commitment in developing the society’s history, library and archives.

Prices given include the buyer’s premium. The society’s website is www.southernfolkpotterysociety.com.