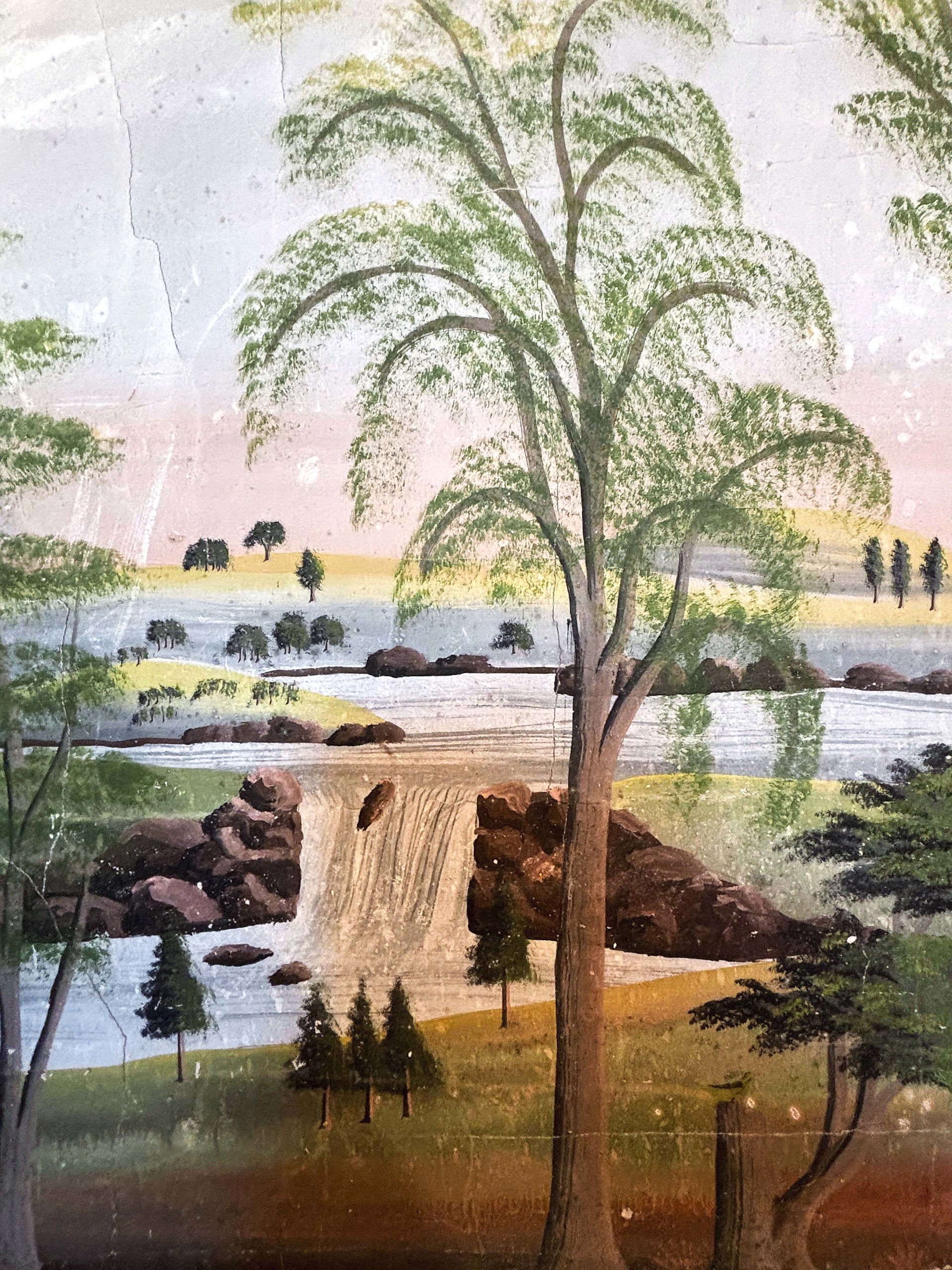

Detail of a waterfall.

By Mike Lowe

BRIDGTON, MAINE — A new $2 million gallery at the Rufus Porter Museum of Art and Ingenuity features remarkable, preserved wall murals by Jonathan D. Poor, offering a unique glimpse into Nineteenth Century life and art.

The Graham Center stands out in stark difference to the older buildings on the small campus of the Rufus Porter Museum at the corner of Church and Main Streets.

The red-painted Church House, the museum’s home since its founding in 2005, was built in 1789 and features a parlor with an in situ wall mural attributed to the Rufus Porter School of Landscape Wall Painting. The museum’s namesake, Rufus Porter, was a brilliant individual who spent his formative years in Maine and later became a prominent American artist, inventor and author in the 1800s.

The white-painted Webb House, built in 1836, includes rooms dedicated to Porter’s inventions and early artwork.

Floors creak in both buildings as you walk through.

The Graham Center, a $2 million gallery and education center, was just completed a year ago.

It lacks the history and nostalgia of the other buildings, but, along with its contents, it is clearly the jewel of the Rufus Porter Museum.

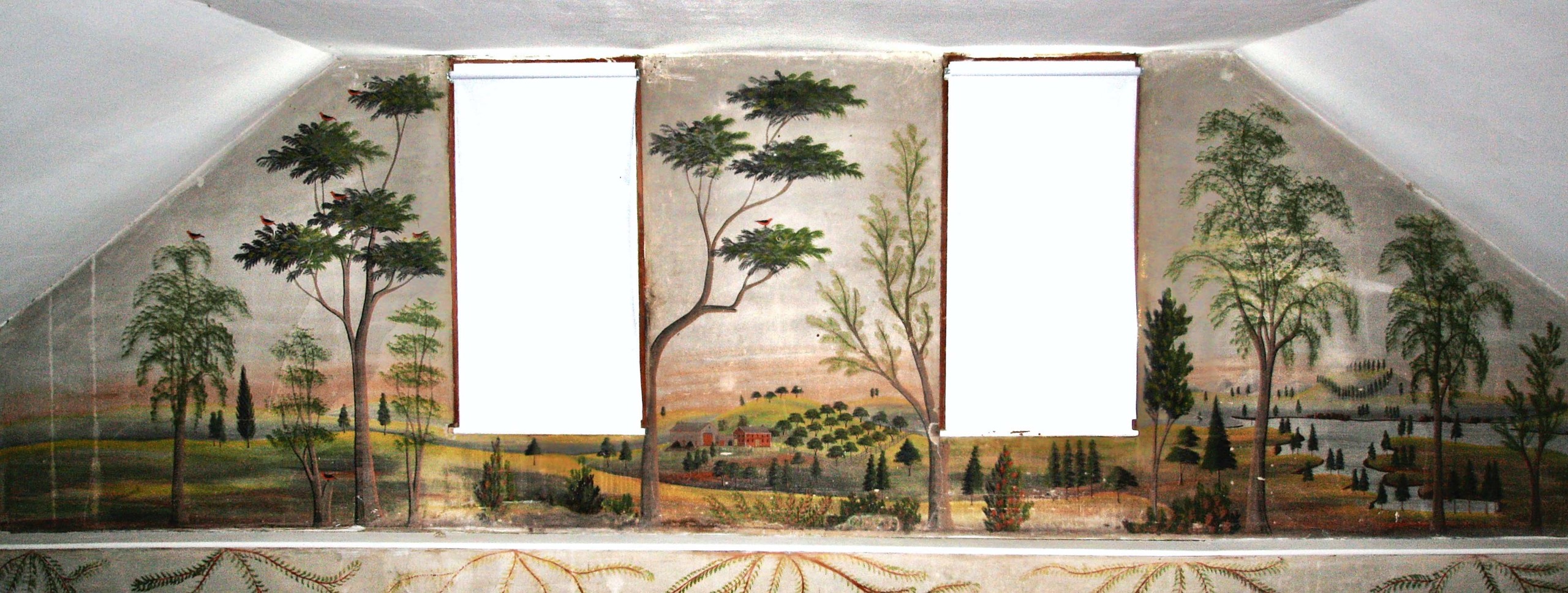

Norton House master bedroom wall panels, reinstalled at the Graham Center.

For when you walk through its large glass doors, you are transported to the mid 1800s. Inside the Graham Center is a unique set of decorative wall murals that rise to the second floor from a nearby home that were hand-painted by Porter’s nephew Jonathan D. Poor in 1840. They were given to the museum in 2011.

“You could say this is a time capsule,” said David Ottinger, a conservationist who helped extract the walls from the Dr James Norton House in East Baldwin, Maine, transport them about 12 miles to Bridgton, then reconstructed them in the Graham Center. “These paintings are extraordinary because there has been so little work done on them. They’re in quite a remarkable state of preservation. A lot of [wall murals], being parts of houses, got covered up, got wallpapered or painted over.

“These are remarkable in that way. I suspect that there were a lot more places that had these paintings in the early to mid Nineteenth Century and very few survived intact as these have. These are probably, as a group, the best example of Jonathan D. Poor walls that I’m aware of.”

Even with some minor water damage, the murals are in exceptional condition. And they put a spotlight squarely on both the museum and Poor, an under-appreciated artist who is often lost in the shadow of his more famous uncle.

Conservationist David Ottinger.

Poor, born in what’s now Sebago, Maine, in 1807, was the son of Porter’s sister Ruth. He died on September 10, 1845. Not much is known of his life other than that he traveled with Rufus Porter to Massachusetts as a teenager and served as an apprentice, learning skills he perfected as a decorative painter. At some point, he returned to Maine, where he became a prolific wall mural artist. There are at least 12 signed murals signifying his work throughout Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

Jane E. Radcliffe, an independent museum consultant, has studied Poor’s works for decades and said the Norton House murals showcase Poor at his best.

“These are the peak of Jonathan D. Poor’s work,” said Radcliffe, a Rufus Porter Museum trustee who is also on the board of the Center for Painted Wall Preservation in Hallowell, Maine. “As you really begin to look at all his work, especially around Maine, he’s building up to this. The Norton walls have incredible details, for instance: piles of manure on the side of the barns, laundry hanging to dry, details like that. You do find those in other murals, but not to this extent.”

There are examples of Poor’s artwork on exhibit in other museums, such as the Moses Mason House in Bethel, Maine, and the Van Gorden-Williams Library & Archives of the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum in Lexington, Mass.

Top floor at the Norton House, prior to removal.

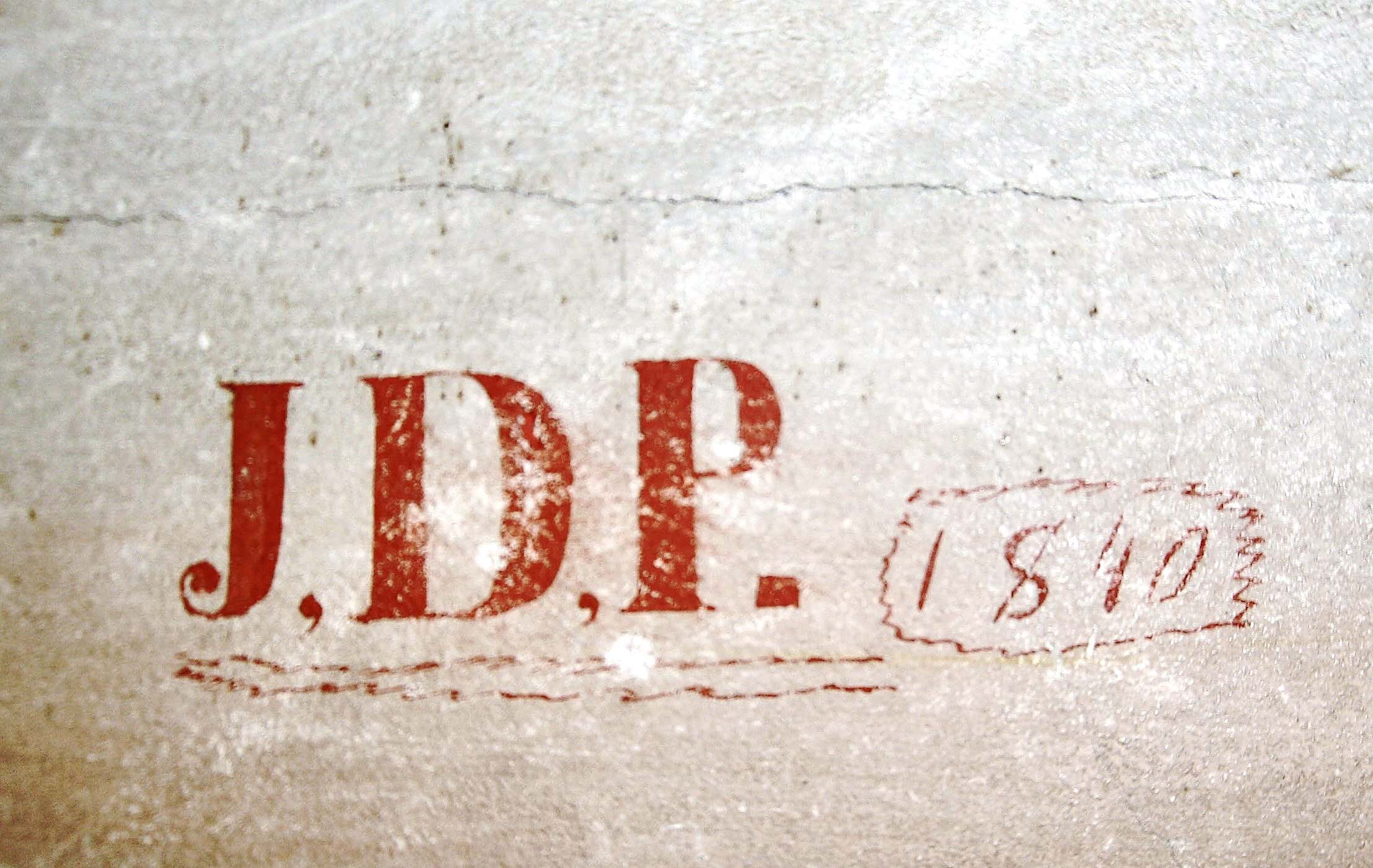

But, the Norton House murals in the Graham Center are the only place where you see how the murals are all connected, not just as a panel on a wall. There is a foyer, a “Good Morning” staircase (which leads to a landing with a room on each side, so inhabitants can step out and say “good morning” to each other) and two bedrooms on the second floor. Poor’s initials, JDP, are signed at the top of the staircase along with the date, 1840.

“You get much more of a sense of the place than when you have one or two walls or don’t show them in a room setting,” said Radcliffe, who co-authored, with Linda Carter Lefko, one of the essential Rufus Porter books, Folk Art Murals of the Rufus Porter School New England Landscapes 1825-1845. “It’s great the way they have them set up.”

And museum officials hope that helps set them apart from other museums.

“The Graham Center allows us to open our doors, literally and figuratively, to the community in ways we weren’t able to before, with just the two houses,” said Dan Dinsmore, the executive director of the museum. “This allows us to go from being a small museum to something much more. It allows us to reach a much larger audience because we have the space to. And the murals are essential to that.

Norton House staircase wall panels, reinstalled at the Graham Center.

“These walls represent a different time. You can walk through the rooms and see life as it was in the early Nineteenth Century.”

The second-floor murals were open to the public last summer. When the museum opened its doors for the season on June 7, the foyer and staircase were complete. A grand opening ceremony will be held at 3 pm on Friday, June 20.

“This has brought the museum up to a totally different level than what we began with,” said trustee Therese Johnson, a former board president. “We had to make a decision: Are we going to stay a tiny entity and what we were, or were we going to take a leap of faith and build (the Graham Center)? We knew something had to be done. And we’ve gone from a little museum to almost an institution now.”

To understand Jonathan D. Poor and his imprint on folk art painting, you must first understand Rufus Porter. And the Rufus Porter Museum attempts to do just that.

“The mission was to recognize the importance of Rufus Porter, who spent his childhood in Bridgton and is a very important part of the art history of Bridgton,” said Julie Lindberg, one of the museum co-founders with the late Beth Cossey. “Nobody had paid much attention to it. And if it hadn’t been for Beth, it wouldn’t have gotten very far. She was the driving force.”

Large wall at the Norton House, prior to removal.

Born in Boxford, Mass., on May 1, 1792, Porter lived a remarkable life — he was called “the Yankee DaVinci” by Time magazine — until he died on August 13, 1884. His family moved to the District of Maine when he was 8, he attended Fryeburg Academy when he was 11, then moved to Portland when he was 18. That’s where he learned the trade of decorative painting before beginning a career that included just about everything.

He was an itinerant artist, an author (his do-it-yourself guide called A Select Collection of Valuable & Curious Arts, and Interesting Experiments had five printings and can still be purchased), a musician, an inventor (he secured 24 patents) and a publisher (he founded Scientific American magazine).

Porter first gained fame as a miniature portrait artist, where his deft handiwork produced, in his words, “correct likenesses” for as little as 20 cents or as much as $8 (on ivory). Jean Lipman, who authored two books on Porter in the Twentieth Century, estimated he painted around 1,000 miniature portraits.

He graduated to painting wall murals around 1820 and quickly established himself as a master. His influence on others became obvious, known as the Rufus Porter School of Landscape Mural Painting, with his nephew Poor, his greatest student.

Detail of an observatory.

Porter stopped painting wall murals sometime in the 1840s to go on to other things. A half-century before the Wright brothers made their first flight, he attempted to build an “aeroport” or “aerial steamer” to carry people from New York to California during the 1849 Gold Rush, and he later started Scientific American magazine.

Poor returned to Maine after helping Porter paint several wall murals in Massachusetts and began his career as a prolific artist.

“We know of at least 12 (murals) that are signed and there may be many, many more,” said Radcliffe.

“Many that are said to be Rufus Porter are actually Jonathan D. Poor.”

Radcliffe said there are clear differences between the two, especially in Poor’s later paintings. While Poor follows Porter’s basic formula, which is detailed in Curious Arts, he adds flourishes of his own. For instance, said Radcliffe, Poor tended to paint apple orchards on his murals while Porter painted open fields.

Both included houses and water scenes. Both had lighthouses or, in many of Porter’s paintings, a building that appears to be the Portland Observatory.

Detail showing a distant village.

But Porter painted trees, especially graceful stately elms, while Poor favored red-flowered sumac. Poor also painted many birds, notably scarlet tanagers, and added details to his buildings.

Tom Johnson, who had a 40-year career in museums and served as the interim director of the Rufus Porter Museum during its capital campaign to construct the Graham Center, put together a list of every item he found in the Norton House murals.

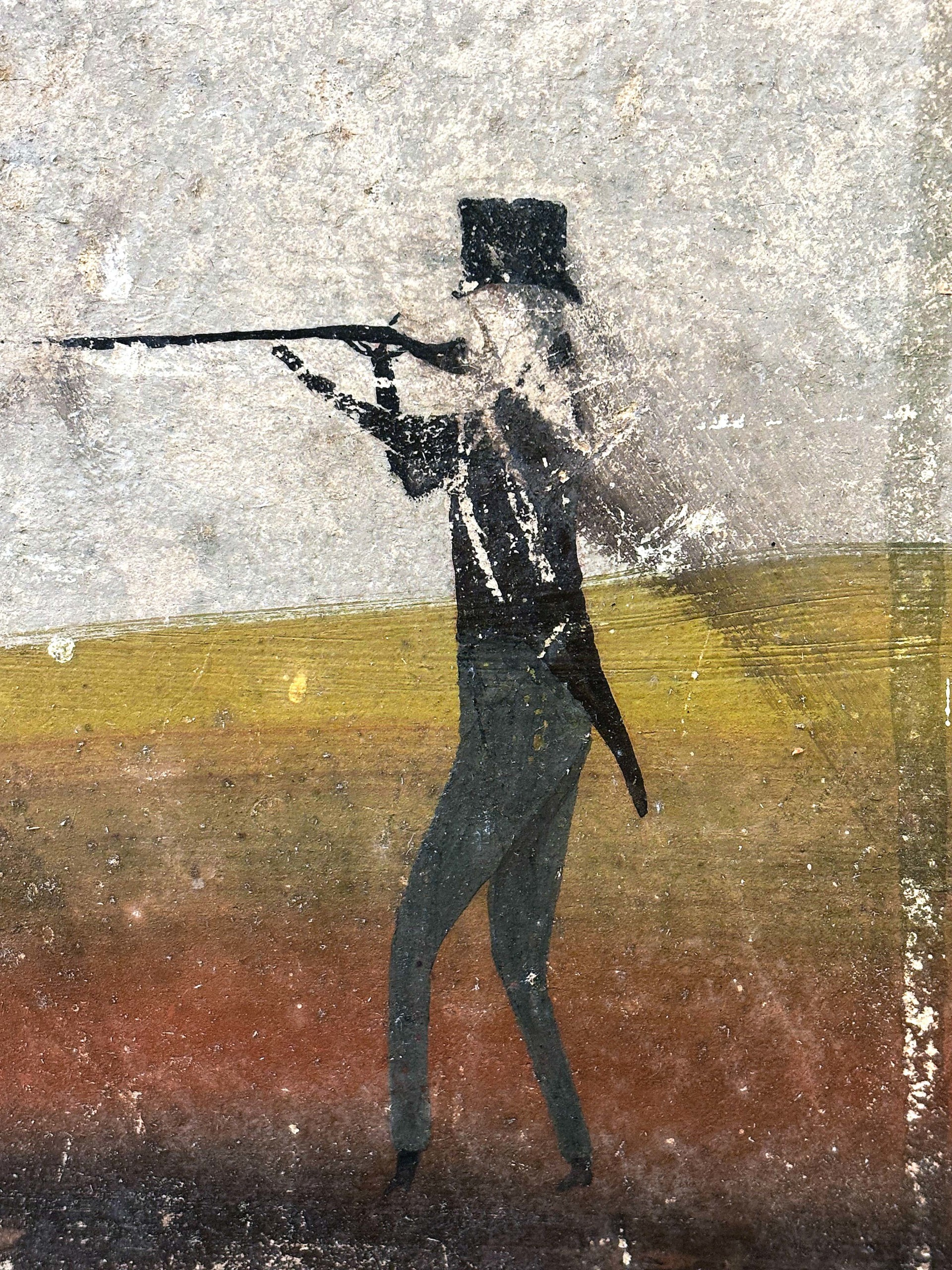

They include, in addition to the piles of manure and drying clothes: 13 red birds, 19 black birds, two yellow birds, a bird house, a hunter aiming his rifle at a raptor that is eating its prey on a fallen branch, a ship’s flag inscribed with “USA,” a barn dovecote, a waterfall, a split-rail fence and, of course, a man in a top hat sailing in a skiff — a trademark of both Poor and his uncle.

There is also a signpost proclaiming “J. Norton Hotel 1820” in one of the mural panels.

“These murals were the height of (Poor’s) style, they really are,” said Radcliffe. “The others, like in the 1830s, were very early in his career. They are much more stark and Rufus Porter-y. [Poor] developed his own style. There’s a lot more whimsey and personality in his murals.”

Detail of a tall ship.

Johnson has spent hours studying the murals. He said he finds something new to appreciate each time.

“I’ve looked at these things hundreds of times,” he said. “And I still see new things. We are looking at the mural with the most details, for sure. They are fascinating. And they don’t necessarily reflect reality, but a stylized representation of reality.”

It’s not known why Poor painted the murals for Norton, the most common theory being they were payment for treatment the doctor provided his family. Poor’s wife, Caroline, died the year he painted the murals.

Regardless of why, the murals leave a lasting effect on anyone who sees them.

“While not quite in situ, it gives people something other than just seeing a section [of a wall mural],” said Barbara Yates, the president of the museum’s board of trustees. “You see the whole thing. You get a feeling for what it was like to live with someone’s creation.”

Yates also loves “the flights of fancy” in the murals, saying, “They incorporate elements of real scenes, but also have an imaginative quality to them that I find fascinating.”

The Graham Center features more than just the Norton House murals, which are located on the second floor in the Julie and Carl Lindberg Gallery. The first floor displays other murals, including two by Porter from what’s considered his best work, from the Howe House in Westwood, Mass. There are also other examples of Poor murals, from the Silas Burbank House in Mount Vernon, Maine, and one from John Avery, another disciple of the Porter School.

Photograph of JD Poor’s signed initials.

Just how the Rufus Porter Museum came into possession of the Norton House murals and how the Graham Center was built is another story worth telling.

The murals were donated to the museum by Glenn and Norma Haines in 2011. The Haines had bought the 1838 Cape-style house in the early 1980s and worked hard to preserve the walls. When they decided to sell the house, they approached the museum and deeded the walls to it.

“That was very generous of them,” said Lindberg. “They bought the house to preserve it, and they did preserve — and maintain it. They saved the murals because they wanted to be part of the history of the town. And the best way to save them was to get them into the institution.”

At the time, Glenn Haines told Bob Keyes of the Portland (Maine) Press Herald, “We lived for those four walls for 20 some-odd years. At this point, to see them in a public domain, never to be sold and always available to be viewed … This is what we always wanted to see happen.”

After being carefully extracted from the home (which was rebuilt at a cost of about $100,000 by the museum), the murals stayed in storage for over 10 years.

Wall being removed from the Norton House.

Lindberg and museum officials knew they had to be put on display, but there was no space in the existing buildings at the Rufus Porter Museum. So, the museum began an ambitious capital campaign called “Raise the Rufus.”

“Our original goal was $600,000,” said Judy Graham, a board member and head of the capital campaign. “We were all quite naive.”

But they never relented. Spurred on by Cossey, the museum co-founder who passed away on October 25, 2024, the group eventually raised $2.3 million.

“Some people in Bridgton were very generous,” said Graham. “We just kept asking and we got there. I’m just profoundly proud of what we’ve accomplished. We’re just this little town in rural Maine and somehow we’ve done it. And it’s gorgeous.”

“We’re very grateful to the people who were so generous to us,” said Johnson. “To build that building, without any debt, is amazing.”

Graham said most donors knew they were helping save a piece of history.

Top step panel from the Norton House, prior to removal.

“We knew we had to get the murals (out of storage) and we knew they were the best of the best,” she said. “These murals are phenomenal… And if we didn’t save them, no one would.”

“Jonathan D. Poor painted a lot of murals,” said Lindberg, “and he signed them, so you could tell what his motifs were and how you identified them. None are as brilliant as this set. These are the very best he did.”

By displaying the murals, said Lindberg, “We are letting the country know, the folk art world know, that [the murals] are available to view, and they are important and they are why Jonathan D. Poor is one of the top folk art painters.”

Johnson, who remains an advisor to the museum, called this “a transformative moment for downtown Bridgton.

“Thirty years ago, this wouldn’t have happened here. It just wouldn’t have.”

Yates calls this a “new era” for the museum, which has shown a steady attendance increase over the years. Last year, it drew 1,222 visitors during its June-to-October season, an increase of 235 from 2023. The hope is that the Graham Center and Norton House murals will attract even more people to Bridgton.

But the ability to switch out exhibits on the second floor is also very important.

“We have room to add new things or change things up,” said Yates. “Change is an important thing for a museum. Too many people think of museums as dead places. One of the things I hope we can show the people in Bridgton, and the larger community, is that history and art are living things.”

The Rufus Porter Museum campus is at 121 Main Street. For information, 207-647-2828 or www.rufusportermuseum.org.

[Editor’s note: Mike Lowe has a deep interest in Maine history and had a 40-year career as a reporter for the Portland Press Herald.]