The Harvard Art Museums recently published Catalogue of the Feinberg Collection of Japanese Art by Rachel Saunders, a book dedicated to the unparalleled collection of Robert S. and Betsy G. Feinberg. The couple built their collection over a period of almost 50 years, and the new publication edited by Saunders catalogs in detail the more than 300 works comprised in it. We sat down with Saunders, the art museums’ Abby Aldrich Rockefeller curator of Asian art, to learn more about this remarkable collection and its contribution to the art museums’ scholarship.

Tell us a bit about Robert and Betsy Feinberg. What spurred them on the nearly five-decade journey to assemble their collection of Edo period Japanese painting?

Betsy and Bob began collecting after a chance encounter in the gift shop of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with a poster that reproduced an image of a Nanban screen. They were stopped in their tracks by the image, the like of which – including the depiction of European foreigners from Edo period eyes – they had not seen before. Some judicious advice showed them that original works of Japanese art were, to their great surprise, in fact available at relatively affordable prices at that time, and so began a journey of discovery and sharing that has continued for decades. This has culminated in the extraordinary promised gift of the collection to the Harvard Art Museums.

Three hundred works sounds like a lot. Is the collection the largest of its kind?

The collection is indeed notable for its size, but also for its comprehensiveness and quality.

What is represented, and what kinds of objects comprise the collection?

The collection includes works from almost all of the major painting lineages active during the Edo period, including so-called literati painting, Rinpa painting, Maruyama-Shijo painting, ukiyo-e, Kano, “Eccentrics,” and on… The collection is also strong in some areas that are not conventionally collected in Japan, such as fan paintings and sliding door-format paintings.

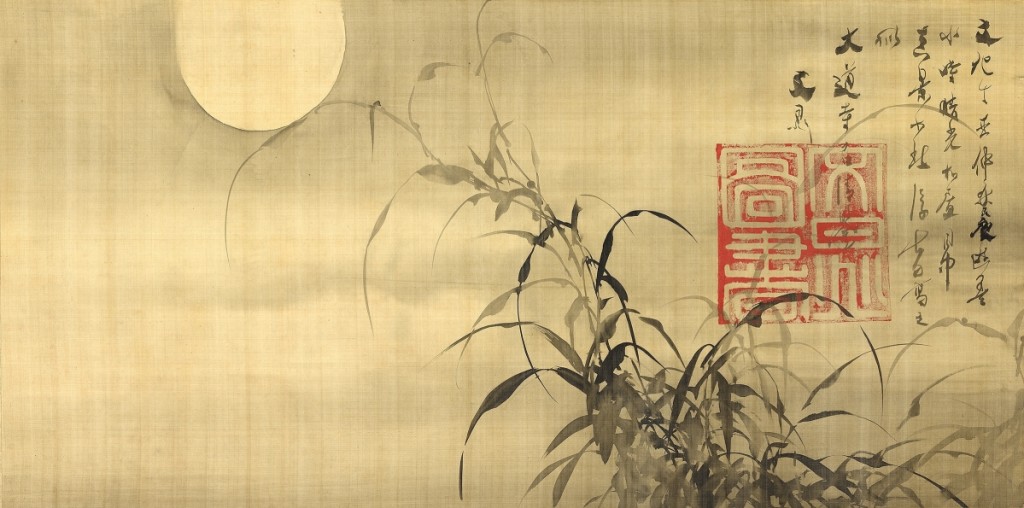

Tani Buncho, “Grasses and Moon,” Japanese, Edo period, 1817. Hanging scroll; ink on silk. Harvard Art Museums, Promised gift of Robert S. and Betsy G. Feinberg. Image: John Tsantes and Neil Greentree; ©Robert Feinberg.

Edo-Rinpa painting is said to be a particular strength of the collection. Can you describe it?

Rinpa painting, which was known as “School of Korin” (Korin-ha) painting in the Edo period, is less a “school” than a loose agglomeration of artists who worked in the footsteps of previous masters, whom they had very often not met. Their paintings are often described as “decorative,” though I would argue that’s a misunderstanding that has “stuck” after Japanese paintings were first “discovered” in Europe in the Nineteenth Century. Rinpa paintings often feature motifs from classical literature and paintings, in many cases dramatically enlarged and isolated, and rendered using fine mineral pigments and precious metals, such as gold and silver. Much of this cultural heritage was associated with Kyoto, the old imperial and cultural capital of Japan. Painters such as Sakai Hoitsu and Suzuki Kiitsu, working in the new shogunal capital of Edo in the east of the country, adapted “Rinpa” idioms to the Edo cultural milieu, adjusting its visual and literary language to suit the needs and tastes of Edo patrons.

What was happening in Japan socially, politically and economically during the Edo period?

That’s a big question! And one on which much ink has been spilled. It’s often described as a period of peace and isolation from the outside world, which again is a misunderstanding that has much to do with how it suited Westerners to interpret Japan in the Nineteenth Century, a picture that has endured in many ways in the “image” of Japan today. The archipelago was indeed distant from the western perspective, but contact with foreigners was not absent, it was simply highly selective and controlled. People, objects and, most importantly, ideas did find their way in and out of the islands. In terms of peaceful – yes, relatively so, after the almost incessant warfare of the previous centuries. It was during the Edo period that what we understand today as a “state” began to develop and coalesce from the many independent “kuni” (provinces). What is often overlooked is the urban development of Edo as a city – by the middle of the Eighteenth Century it dwarfs contemporary London or Paris with more than a million inhabitants. We also see the rise of the merchant class, who, while occupying a low rung in the official class system, in fact quickly come to outpace the samurai rulers in terms of access to financial resources. The rise of this class is, in simple terms, one of the big factors that led to the massive diversification of painting styles and just the sheer number of paintings produced for patrons during the period.

What brought that period to its end?

Again, there’s a huge amount of scholarship around this question. It’s far too often simplistically attributed to the arrival of foreigners in the 1850s. While their arrival certainly did put great pressure on the shogunate, there were many other factors in play behind the uprising and imperial restoration (Meiji restoration). Many of these factors are economic, as well as social, and poorly handled natural disasters also played a part.

What led you and your team to put the catalog together?

We created an exhibition catalog to accompany our “Painting Edo” exhibition, and a full catalogue raisonné of the collection. The two books were designed to complement each other and to offer different modes of access to the collection. The exhibition catalog offers a sweeping history of Edo painting through co-curator Yukio Lippit’s essay, and a deep dive into a particularly important cycle of paintings by Sakai Hoitsu in the collection, which is told through my essay. As such, it reflects two of the ways in which the collection has impact in our daily work as art historians, on both the macro and micro levels. The Feinberg collection catalog contains full photography of the entire collection, as well as text entries on all the paintings, and the sculpture, which is also part of the collection (but not the exhibition). It was the moment to bring together the intellectual resources and momentum of our team, which included graduate students, in the preparation of the exhibition and catalog.

Installation view of “Flowers of the Four Seasons” in the exhibition “Painting Edo: Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection” at the Harvard Art Museums. Photo: Mary Kocol; ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Do you have a favorite work in the collection that speaks to you?

That’s a really tough question! There are so many wonderful works, and now that we have put together the exhibition and explored so much further through the publications and ongoing programming, the way I see individual works is continually evolving. Tani Buncho’s “Grasses and Moon,” for example, which pictures a moon viewing party that took place in Edo in such a way that the viewer is overwhelmed by a sense of “thereness” despite the simplicity of this (admittedly very large) ink painting, is a painting that came to have new nuances for me as the pandemic brought about such prolonged and intense social isolation. The idea behind harvest moon viewing has for centuries been that even if physically separated, we might still feel togetherness in all looking at the same moon in the same sky on the same night every year.

While working with our fantastic colleagues at the Arnold Arboretum on a series of partner programs last year, they helped me see a pair of I’nen School folding screens, “Flowers of the Four Seasons,” with new eyes. Discovering how the artist had incorporated incredibly detailed botanical observations into what I had always understood as a much more aesthetically oriented style of painting was thrilling.

I also love the intimacy of many of the fan paintings. We featured some of these in the “Painting Edo” exhibition by creating a contemporary interpretation of the “floating fans” (ogi nagashi) motif, a conventionalized painting subject in which decorated fans are pictured being washed away at the end of summer on a river.

Are there more than the Edo period works in the collection?

Yes. The Feinbergs have also had a long-term interest in Japanese sculpture of all eras. Their collection includes a small group of Buddhist sculpture from the medieval to early modern periods, which has also been promised to Harvard (and detailed in the new Feinberg collection catalog). Betsy and Bob are also collectors of Japanese ceramics, and their significant collection of ceramics is generously promised to the Walters Art Museum.

The Covid-19 pandemic has upended so much in society at large and especially museum exhibitions. Will the museums’ major presentation of the Feinbergs’ collection, “Painting Edo: Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection,” which had to close in March 2020, be reopened this year?

Our staff are working closely with officials at the university to estimate a safe reopening date. As of the date of this response, we remain closed and do not have a reopening date targeted.

Installation view of fans by Suzuki Kiitsu in the exhibition “Painting Edo: Japanese Art from the Feinberg Collection” at the Harvard Art Museums. Photo: Mary Kocol; ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

What other ways have you been able to promote it?

Thanks to the work of colleagues across the museum and the university, we were able to pivot very quickly to offering free online programs for the public and to our members. Over the last year we have offered several online talks and lectures that explore various themes and objects in the exhibition, including a fun partnership with the Arnold Arboretum where we discussed comparisons between live specimens in their collections with painted depictions in the Feinberg collection. These programs were all recorded and join other short, prerecorded talks compiled into Vimeo and YouTube channels dedicated to the exhibition. We also launched four beautiful virtual tours of the exhibition on Google Arts & Culture – these offer rich imagery of individual objects in the show, as well as installation views of the galleries. These assets all provide a great way for visitors to leisurely explore the exhibition. We’ll continue to host more programs this spring. We’ve just begun another collaboration with the Arnold Arboretum – Haiku and You – in which we’re inviting the community to channel their inner poet and slow down, look closely and see from a different perspective. We’re hoping to encourage a burst of haiku writing, from observation of the paintings on our website, visits to the Arboretum, or wherever inspiration may be drawn. I hope your readers will join us and submit their haiku to become a published poet! Details about future programs and links to the digital assets I mentioned can be found on our website at harvardartmuseums.org/paintingedo. To get right to the Haiku and You project, go to hvrd.art/haikuandyou.

What does the museums’ stewardship of the Feinbergs’ collection entail?

The museums’ stewardship of the collection ensures access by students, faculty, scholars and the public, and allows for teaching, research and further documentation of these paintings. Aside from the “Painting Edo” exhibition, we have consistently displayed a selection of paintings from the collection in our galleries since our facility reopened in late 2014 after renovation, and we teach with the collection constantly – even online during the pandemic – in classes that range from neuropsychology to medicine to art history. When the museum reopens, we will be extremely fortunate to be able to continue to offer appointments in our Art Study Center, so that anyone may reserve time, in advance, to view the paintings and other works in the collection that are not on view in our galleries. Art historically, the collection brings us a huge step closer to being able to teach a comprehensive history of art created in Japan through original objects. More philosophically, the collection is constantly in action in the galleries as well as online where its potential to facilitate not only close art historical scholarship, but also simply the ability to see differently is palpable.

-W.A. Demers.

Both catalogs are available for purchase at Harvard Art Museums shop. The Catalogue of the Feinberg Collection of Japanese Art is available for purchase here, and Painting Edo: Selections from the Feinberg Collection of Japanese Art is available here.