Lisa Slominski, an American curator, writer and cultural producer based in London, is out with a new book, Nonconformers: A New History of Self-Taught Artists, due April 19. A lecturer on the topic of “Outsider Art,” she assembled contributions by several scholars to produce a study of more than 60 self-taught artists from around the world. On the heels of Christie’s $2.2 million sale of Outsider Art early last month and New York’s staple fair conducted earlier this month, Antiques and The Arts Weekly checked with the author to get a better understanding of why buyers flock to it to broaden their collections’ horizons.

Congratulations on producing this beautiful book. Why this examination of the field, and why now?

The interest in and critical acclaim for artists often described as self-taught, outliers or “Outsiders” has been gaining traction for decades; however, more recently we are seeing a shift in, or questioning of, the potential restrictive lens propelling these artists. The term “Outsider Art” emerged 50 years ago as the title for Roger Cardinal’s book, which has become a wildly successful categorical phrase, as well as a powerful branding tool. Currently, we are witnessing the art world rightfully positioning these makers into Twentieth Century art history – looking at William Edmondson in relation to Modernism and Janet Sobel’s contribution to Abstract Expressionism – and we’re seeing artists that are often connected to the precursor “self-taught” or “Outsider” exhibited alongside contemporary artists. Next month’s Venice Biennale features three artists featured in Nonconformers: Sister Gertrude Morgan, Minnie Evans and Niki de Saint Phalle.

Significantly, we are developing recognition of how artists considered within the wider genre are defying assumptions of commonalities. In 2022, we are making individual artistic merit and circumstance paramount, including the consideration of predetermined cultural and personal conditions and how racial oppression, poverty, mental illness and disability could present discriminatory positioning more complex than merely being “self-taught.” Therefore with Nonconformers, my aim is to present a canon of unique, idiosyncratic creatives via a contemporary lens: artists or histories that may still be beyond the readers’ cultural awareness, while simultaneously admitting, examining and exploring the complexities of labeling.

How did you assemble your team of contributors?

I wanted to collaborate with a range of contributors that could bring extensive knowledge and unique perspectives to Nonconformers, so I considered each chapter’s focus to connect with the right person. For example, John Maizels, who founded Raw Vision in 1989, worked directly with Roger Cardinal and attended the 1979 Hayward exhibition, “Outsiders: An Art without Precedent or Tradition,” so his take on the impact of Cardinal’s book, Outsider Art, was incredible to capture. I also wanted contributions from art academics, making Dr Cheryl Finley, a distinguished visiting professor in the department of art and visual culture at Spelman College, an important choice for her perspective on the legacy of Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980.

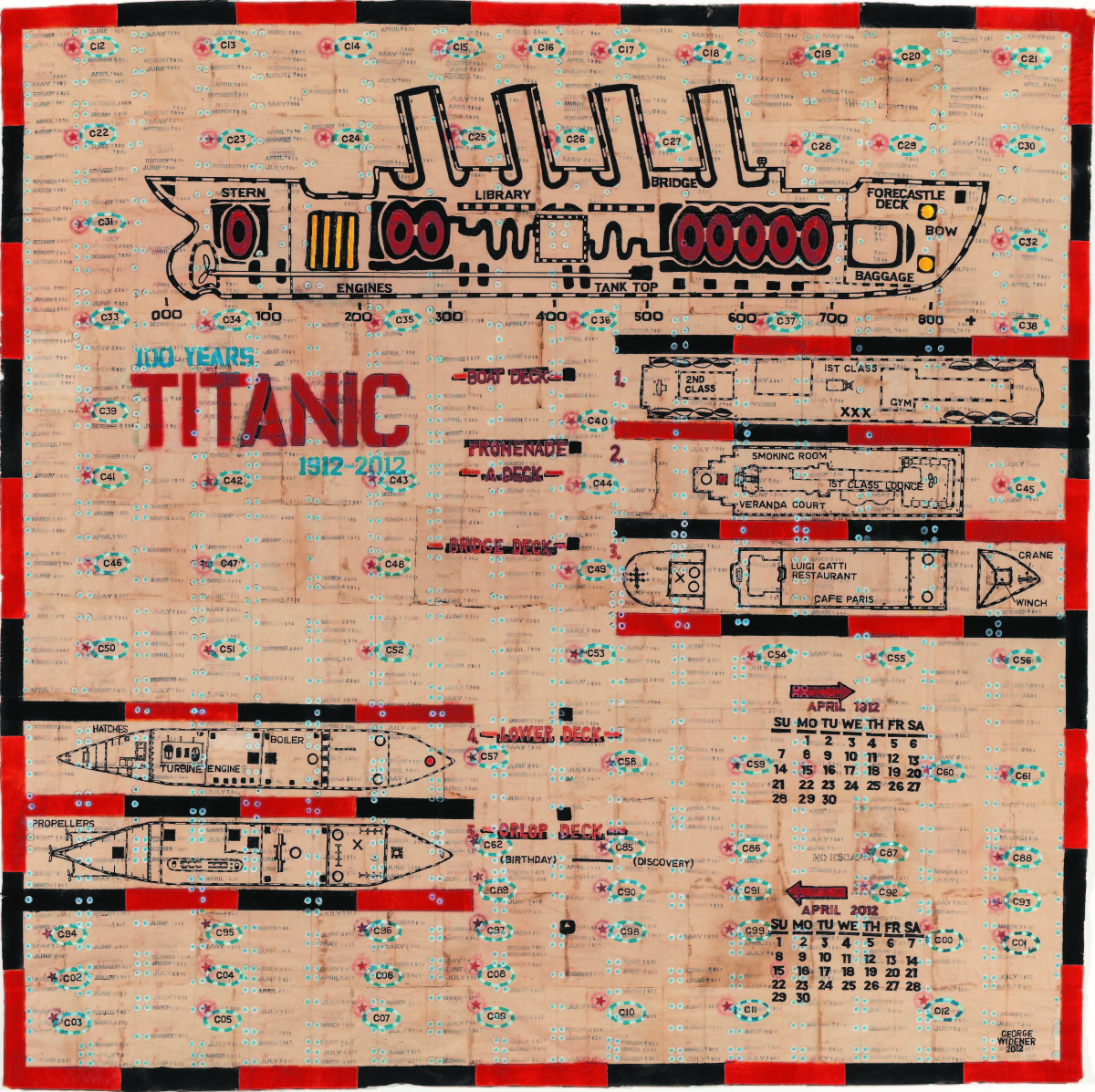

In terms of structuring the types of contributions in Nonconformers, I knew I wanted to include direct voices of living artists, so the three interviewees – George Widener, Mamadou Cisse, and William Scott – are paramount to the book!

George Widener, “Hundred Years Titanic,” GW/P 01, 2012, mixed media on paper, 58-11/16 by 59-13/16 inches. Collection of Victor F. Keen. © Ricco/Maresca Gallery.

What is it about Outsider Art that speaks to collectors?

I can’t speak to the appeal of “Outsider Art” for collectors, but I do think in terms of artists considered self-taught, those historically operating from marginalized positions or contemporary artists who work from studios supporting individuals with intellectual/developmental disability, a current desire to collect and exhibit these artists connects with a greater interest/need for diverse voices and perspectives and the art world’s attempt to shift away from the dominance of academic white male narratives.

Even though Outsider Art has become a catch-all term internationally with fairs operating in both Paris and New York, European self-taught artists seem to have developed separately to that of America. How did these interests develop respectively? And currently operating globally under “Outsider Art” is interest limited to their origins?

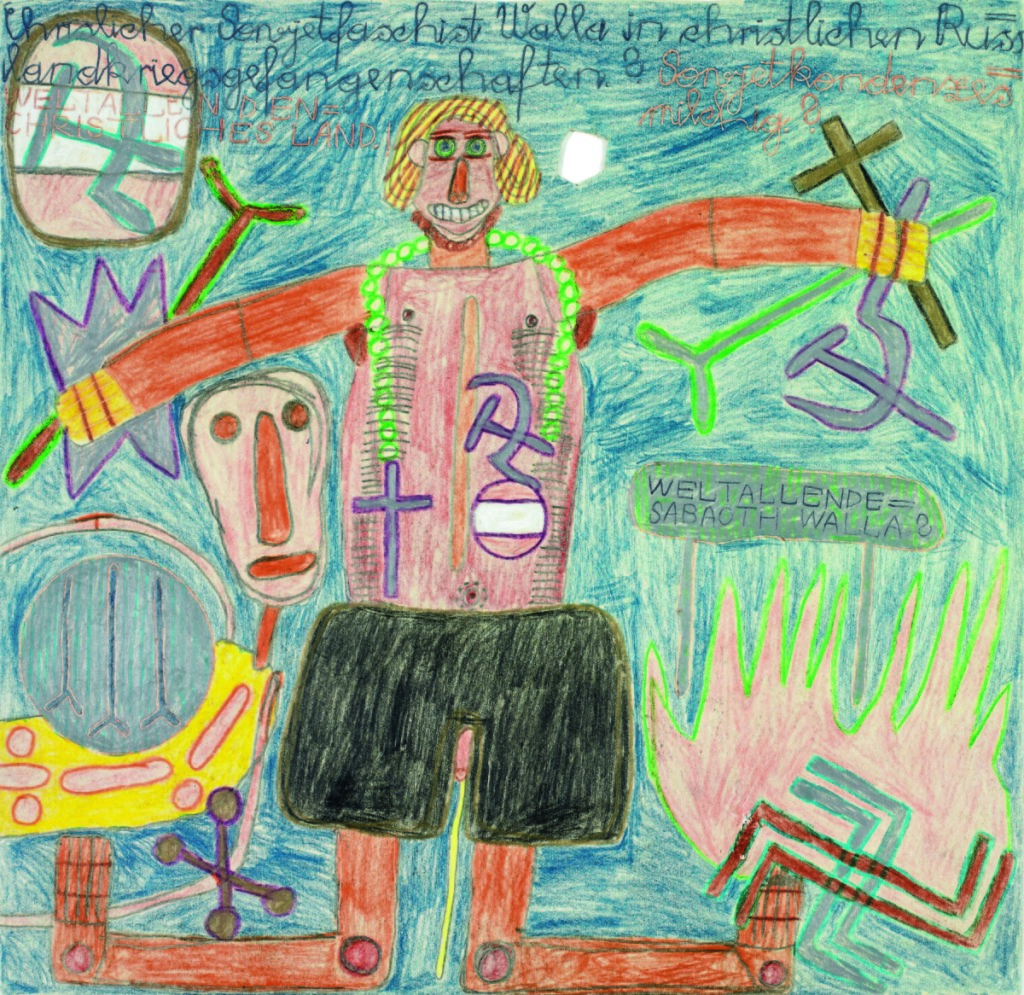

The European cultivation of makers from beyond the cultural mainstream often connects to Artistry of the Mentally Ill, a book of (mostly) drawings by patients of psychiatric hospitals and institutions. Published by German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn in 1922, this prefaced the European connection to creatives with mental illness. In the 1940s, French artist Jean Dubuffet was interested in Prinzhorn’s work and developed the genre of l’Art Brut. Dubuffet’s definition was “work executed by people untouched by artistic culture” and production that is “completely pure” and “raw.” The exhibitions and publications of l’Art Brut were not restricted to but heavily featured makers from psychiatric institutions. Artists Aloise Corbaz and Adolf Wolfli, both confined to institutions, have become emblems of l’Art Brut.

Concurrently in the 1930s, America had developed “Folk Art.” In opposition to Europe’s intrigue for art produced by individuals with mental illness, folk art was rooted in tradition, craft and communal process. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, also introduced the concept of the “Modern Primitive” to present self-taught artists. In 1937, this encompassed its first solo exhibition of an African American artist, William Edmondson. Considering the vast scope of America, further interests in artists operating outside of the cultural mainstream developed over the Twentieth Century. In the Midwest, this included the Chicago Imagists championing self-taught artists in 1960-70s like Joseph Yoakum, and explorations of how Southern African Americans were creating vernacular art reflecting their daily lives and beliefs.

Though not immediate (and not a title/term elected by Cardinal), “Outsider Art” has become a global and universal term ring-fencing historical makers of l’Art Brut, folk and often includes non-academically trained African American artists, those with intellectual/developmental disability, mental health issues, self-taught and/or those operating on the margins of the society – past, present and future. While it seems specific artists remain more desirable in their respective regions, the ubiquity of artists linked to “Outsider” has aided in international appeal. A work by Swiss artist, Adolf Wolfli, sold in America for nearly $1 million at Christie’s, New York. In 2020, Britain’s critically acclaimed exhibition “We Will Walk – Art and Resistance in the American South” at Turner Contemporary included Mary T. Smith, Nellie Mae Rowe and Bill Traylor, all significant self-taught African American artists.

August Walla, “Weltallendechristliches Land

(End of Universe Christian Country!),” n.d., pencil, colored pencil and ballpoint pen on paper, 11-13/16 by 12-3/16 inches.

Art Brut KG. Image © Art Brut KG

So many icons of the genre have been individuals coping with mental illness, substance abuse or lack of social accessibility, such as Martin Ramirez, Henry Darger, Judith Scott and Lee Godie. Is trauma a throughline in this genre?

For me, one of the issues or complexities of navigating the descriptor “Outsider” and at times applicable to self-taught, too, is that the genre has been built on biographical, personal circumstances, such as trauma, rather than artistic concepts, or shared ideas/practices among artists. Many assume particular characteristics inclusive of mental illness, cultural unawareness (including ignorance of their position as an artist) and a raw aesthetic for the totality of the genre. However, every artist mentioned above challenges some aspect of these characteristics. For example, Henry Darger’s oeuvre is abundant with acute literary and cultural references; and Lee Godie was inarguably hyperaware of positioning herself as a professional artist. So while traumatic events are evident in many narratives, they should not be considered a connective concept nor used as a tool for justifying a practice. In other words, I think biographical details, including trauma, can be discussed in a respectful manner that lends to a deeper understanding of an artist’s or maker’s practice, but should not be what validates it.

You imply in your acknowledgments that the language by which we discuss Outsider Art may have a future “expiration date.” What do you mean by that?

In the same way, I feel “Outsider Art” can be problematic in terms of its potential to be othering or restrictive for artists, I understand this was not its intention nor the intention of those developing the field. I am also aware that how we address race, gender, mental health and disability is constantly evolving. In 1904, Henry Darger was admitted to the Illinois Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children; a phrase that certainly wouldn’t be used today. The language describing William Edmondson in MoMA’s 1937 press release is prosed with inherent racism. My intent in Nonconformers is with respect and to allow artists or representatives to self-identify where possible, especially in terms of disability, but I understand language is continuing to progress, potentially rendering mine out of date or restrictive to future generations.

In your essay “Alternative Expressions” in the book, you survey the use of abstraction as concept and process. What did you learn in your interview for this chapter?

The final three chapters look at abstraction, figuration and landscape, each featuring an interview led by Sophia Cosmadopoulos. The interview following the “Alternative Expressions” essay with George Widener is an absolute highlight for me. Widener candidly shares with us the interests and concepts behind his practice, as well as how his own relationship to the term “Outsider Art” has changed over the years.

What kind of future do you see for the category?

My hope for the future diverges between artists and the category. I see the artists gaining further traction and criticality in the wider arts ecology. I’d like Nonconformers to be one of the final books that hold “self-taught” artists to an attempted category and forthcoming they will be further presented in circumstances related to their historical relevance, style and/or process. I have trepidation in predicting how the category or its successful and key affiliates will develop. The American Folk Art Museum has implemented three amendments to its name to adapt to shifting interests and materials. Whether amending the titles of fairs, auctions and institutions linked to “Outsider Art” is likely, and whether such taxonomical amendments would progress or thwart the artists presented – only time will tell.

-W.A. Demers

(Editor’s note: Nonconformers: A New History of Self-Taught Artists by Lisa Slominski, with contributions by Michael Bonesteel, Mamadou Cisse, Sophia Cosmadopoulos, Tom di Maria, Jo Farb Hernandez, Cheryl Finley, Katherine Jentleson, Phillip March Jones, Sarah Lombardi, John Maizels, William Scott and George Widener, April 19, 2022, HC – Paper over board, $45, is available for preorder at booksellers everywhere and at www.yalebooks.yale.edu).