An email sent by Dan Casavant to the general inbox at Antiques and The Arts Weekly posed the query of advertising the sale of a collection of primary source material (ledgers, account books and the like). The origins of his collection sounded like an interesting story, and we asked if he’d be willing to profiled with an interview. His story is below…

Tell our readers a little bit about your collection…does it focus on a particular topic, region or date? If so, what’s the reason for the specialization?

Thanks for speaking with me, Madelia. My inventory of primary source material carries about 800 handwritten journals and another 200 individual documents. Coincidentally, it includes four unique Newtown, Conn., journals: a 1727 doctors’ daybook, a 1795 silversmith account book, an 1842 hatbox makers journal and an 1860 farmers ledger. Ninety-nine percent American, it carries items from all over the country and is particularly strong in Northeast journals. I’ve owned many from Connecticut, and I recently put together a “First Peoples” collection of three journals from New London County, including a 1794 journal from Montville documenting Betty & Eunice Uncas (Uncasville), Hannah Shantup and Henry Quaquaquid.

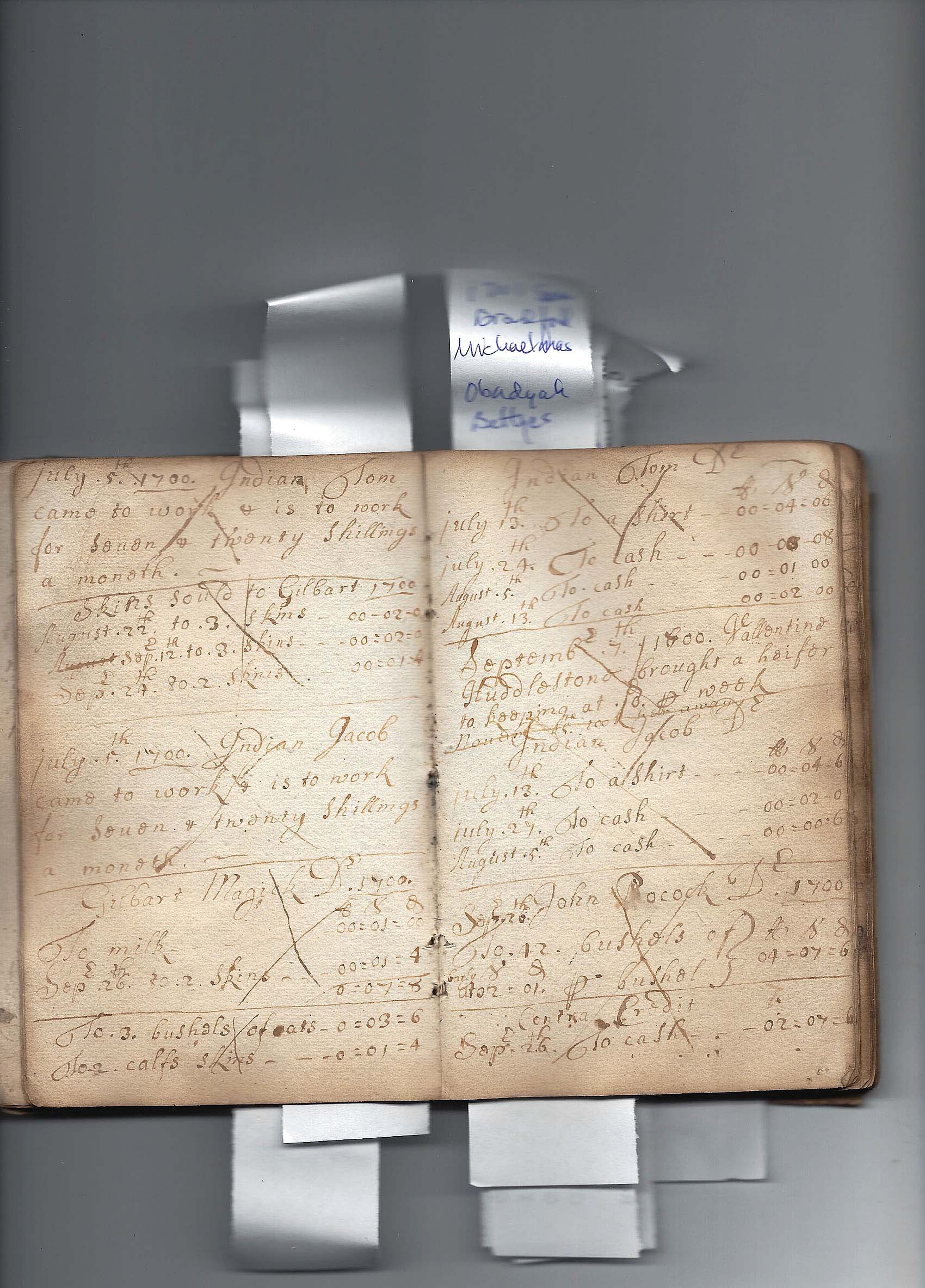

This primary source collection includes diaries, ship logs, ledgers, etc., and covers a number of target areas including nautical, Colonial, women’s studies and decorative arts. Within the past five years, I’ve focused on African and Native American. Historically, these two groups did not speak for themselves: with little to no education, few could read or write. These are the important pieces of history which I try to document with my research.

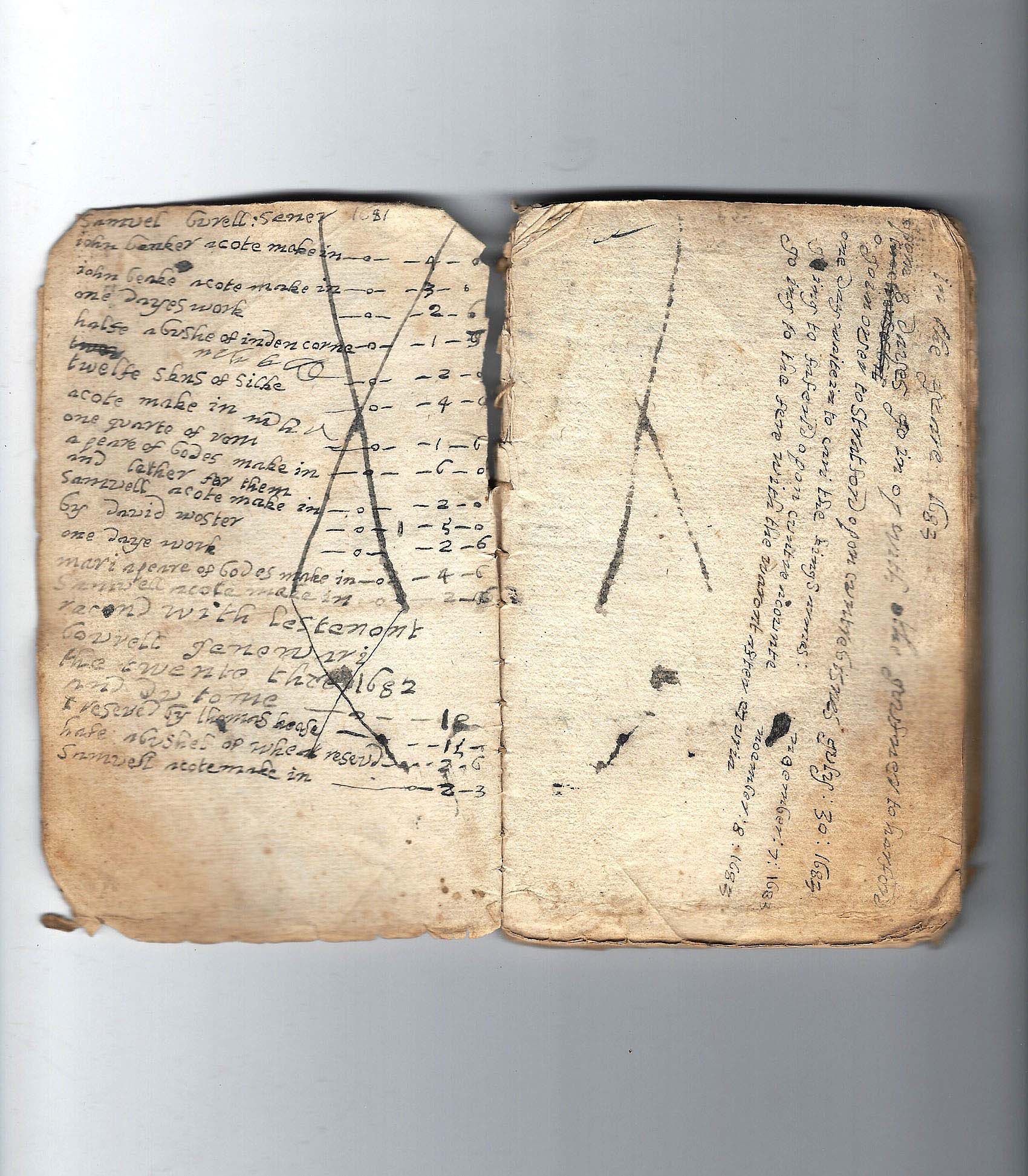

I prefer the rustic or primitive early American account books, daybooks and ledgers. We have some nicer manufactured journals, generally owned by the wealthy, but the handmade pieces, crude, consisting of folded paper sewn together by hand… these speak to me, they’re part of the story.

The rarest among them would include the five Seventeenth Century colonial American journals: a 1675 Tailors Hine family account book from Milford, Conn., in which Hine is a scout for his neighbor the “Gufner” (Governor Robert Treat); two journals beginning in 1684 belonging to the Rolfe family of weavers from Newbury, Mass.; the 1685 Rhode Island account book of Freegift Coggeshall, which documents American Indians as contracted labor; and the 1694 collection of Abraham Jewett cobblers journals from Rowley, Mass. The last is a mate to one already owned by the Clements Library at the University of Michigan.

1679 Hines journal, “8 days going with the gufner (Governor Treat) to Hartford.” Hines was a guide for the governor, traveling in Native American country.

Why specialize?

Most vintage book dealers sell primarily printed books, occasionally we find a manuscript book in their inventory. Printed books are very collectible, but condition is of utmost importance in value. With primary source, condition is a secondary consideration: content is the key to value in handwritten journals. In the beginning, I collected anything handwritten but eventually specialized in handwritten books. I still have a few documents; mostly related to Native and African Americans.

Manuscript primary source is what interested me the most. Our printed history books tend to be an interpretation of history; primary sources often are history themselves. I recognized early that computers were changing language and the way we document our communications. Few people write things on paper anymore. Most people communicate electronically. So, it occurred to me that written language was becoming a thing of the past.

Investment value is also important. The value of antiques and other collectibles tend to run in cycles — usually market controlled. Buyers tend to determine the value of most collectibles. It dawned on me that museums and libraries buy primary source materials, and once acquired by institutions, unlike other collectibles, they never come back on the market. So, supply and demand dictate a favorable consistent long-term trend when it comes to their value.

Primary source is unique, it’s all one of a kind…and often it tells a story, sometimes a story which could be the subject of a movie.

We’ve all heard of the diary of Anne Frank — I own the 1945 diary of Erika Walbrun who wrote, in graphic detail, her firsthand account of her experiences and escape from the bombing of Dresden. Erika’s father somehow made it to America, found work and established his family here.

You mentioned that you started collecting in 1986 — what inspired you to start?

In 1986, I left my state job and went to work in the private sector. I wanted to be paid based on my efforts and not based on politics. My wife and I realized that a job would pay the bills, and everything extra we did in life would get us ahead; we wanted to get ahead. My wife and I both went into real estate, which proved to be a great move for us. As far as collectibles, initially it was a hobby, but the goal was to create an investment in our future.

My sister, with whom I shared a love of history, was an antiques restorer and dealer. I attended auctions and flea markets, starting out as a collector of anything I thought held value. Then, after a few failures, I focused attention on autograph collecting. But with so many forgeries out there corrupting the market, I remembered reading in an autograph grading book that “someday, these old ledgers would be sought after and collected…” and the rest is history. Ledgers were fairly common when I started. Now, almost 40 years later, there is a lot of interest in them, and they don’t last very long in the marketplace. They’ve become a very easy sale for used book dealers.

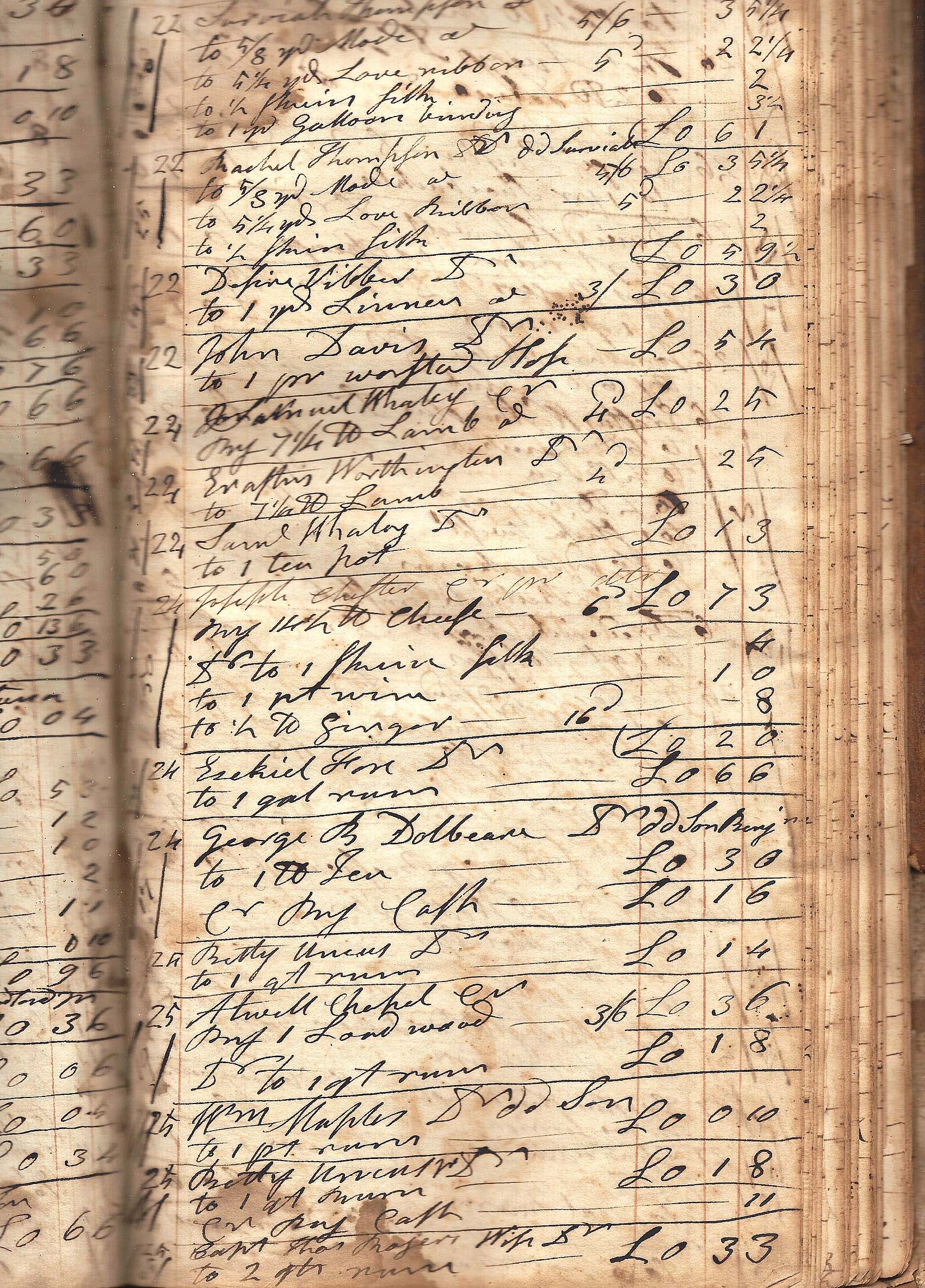

1793 Erastus Worthington journal, two entries for Betty Uncas (Uncasville, Conn.) purchasing quarts of rum.

Is the history within a ledger immediately identifiable?

I love the research involved in identifying exactly what is in a journal. In general, when I purchase a ledger, I don’t really know what it is until I get it home and begin the research. It’s then that a story emerges.

One thing I’ve noticed is that ledgers are often more accurate than the census. While we can use census data to piece together the story, ledgers often hold a more accurate picture of a local population make-up. A census is a one-day snapshot every 10 years. Ledgers consistently define the population in an area over periods of time, picking up people that are otherwise missed in a 10-year gap between enumerations.

What was the first thing you collected?

I studied the trade papers — Antiques and The Arts Weekly and Maine Antiques Digest — for years while trying to learn about ledgers, diaries, ship logs…manuscript books. They fascinated me. My first big purchase came when I met Frank Wood of Dewolfe & Wood in Alfred, Maine. He sold me a very nice Eighteenth Century ledger from China, Maine, which led to my purchase of his entire ledger inventory — two pallets of ledgers. This was part of an inventory belonging to another book collector/dealer who had passed away. That purchase totaled over 300 journals in one effort. I sold half quickly to one buyer, the Connecticut Historical Society. I recall that I paid maybe $27.50 per ledger and I sold them for $35 each. Not big money, but an education and confidence builder, as well as a lot of work.

Can you comment on if certain ledgers are more valuable than others?

In general, the more common ledgers like cobbler, blacksmith and general store ledgers tend to be less valuable, and less interesting. Every town had four or five of each. The more valuable journals belong to specialty trades — gold and silver smiths, glass makers, furniture makers — from when things were made by hand, prior to the Industrial Revolution.

What’s your most recent acquisition?

Recently, I purchased four journals: three involving people of color, two dated before the emancipation. But the most important and interesting of the four would be an 1840s account book from Marshallville, N.J., maintained by the Marshall family who purchased land with the Stanger family (Stanger Glass) and developed the area to establish four glass houses, a wharf, ship building and a company store. Very little remains today of the bustling village the Marshalls created. This journal, once researched, will fill in many blanks, providing new information such as previously unknown glassworks employees.

1678 Coggeshall journal, entries for “Indian Tom” and “Indian Jacob,” two contracted laborers.

You mention you sell your material to libraries — can you share some of the things you’ve handled and where you’ve placed them?

I once placed the colonial ledger of Richard Clarke of Boston with the Massachusetts Historical Society; Clarke was the loyalist merchant whose tea was dumped into the harbor during the Tea Party.

Sometimes a piece is so rare, even a partial survivor is of great importance to libraries. I placed, with the University of Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Library, an 1813 partial Trading Post daybook in the hand of Pierre Menard (Indian Agent), a fur trader, lieutenant governor and slave trader from Kaskaskia, Ill., during the Territorial Period. That piece came with impeccable provenance: ex-Lawrence Lande collection.

I placed another partial ledger with Princeton University’s Firestone Library, one which many would have thrown away; it was just a small portion of the original — tattered, torn, no binding, no covers, soiled and stained. It was an 1858 relic of a former biracial Irish/African American lost safe-haven community called “The Oaks,” off the beaten path in Alamance County, N.C. It was written by the Irishman Francis Ray, neighbor of Green Oldham, a free person of color who had donated land for a “colored” school and church. Relatively wealthy, Green Oldham kept a white servant in his household. It was just very unusual and rare for this time period, documenting this Black Irish community.

I’ve also placed, with the University of Virginia Library, the exceedingly rare Slave Labor Record of Dunmore Alexander, who was the slave blacksmith of Congressman Mark Alexander at Salem Plantation (Mecklenburg, Va.). Dunmore performed work for many locals in Mecklenburg County, and this record was a book of his work and cash receipts.

You’re now thinking about selling — may we ask why?

I’ve attended many auctions in the Northeast as part entertainment and part education. I’ve learned to bid aggressively for the things I wanted. When I started, ledgers were highly undervalued and underappreciated at the time, so I was usually the high bidder. Now my collection is quite large.

Eventually, we had to find a home for all these books, so we finished one of our small bedrooms with bookshelves, purchased some fireproof safes for the more valuable books, and today, my spaces are all filled. Like most libraries, space is at a premium. I began this hobby, largely as a means to support and entertain myself during my retirement. It’s time to sell.

Like the Schoyen collection, this collection will probably not find one buyer and will probably be sold in groups or individually.

—Madelia Hickman Ring

[Editor’s note: For readers interested in possibly acquiring pieces from Casavant’s collection, he can be reached at 207-877-9097 or dancasavantrarebooks@yahoo.com.]