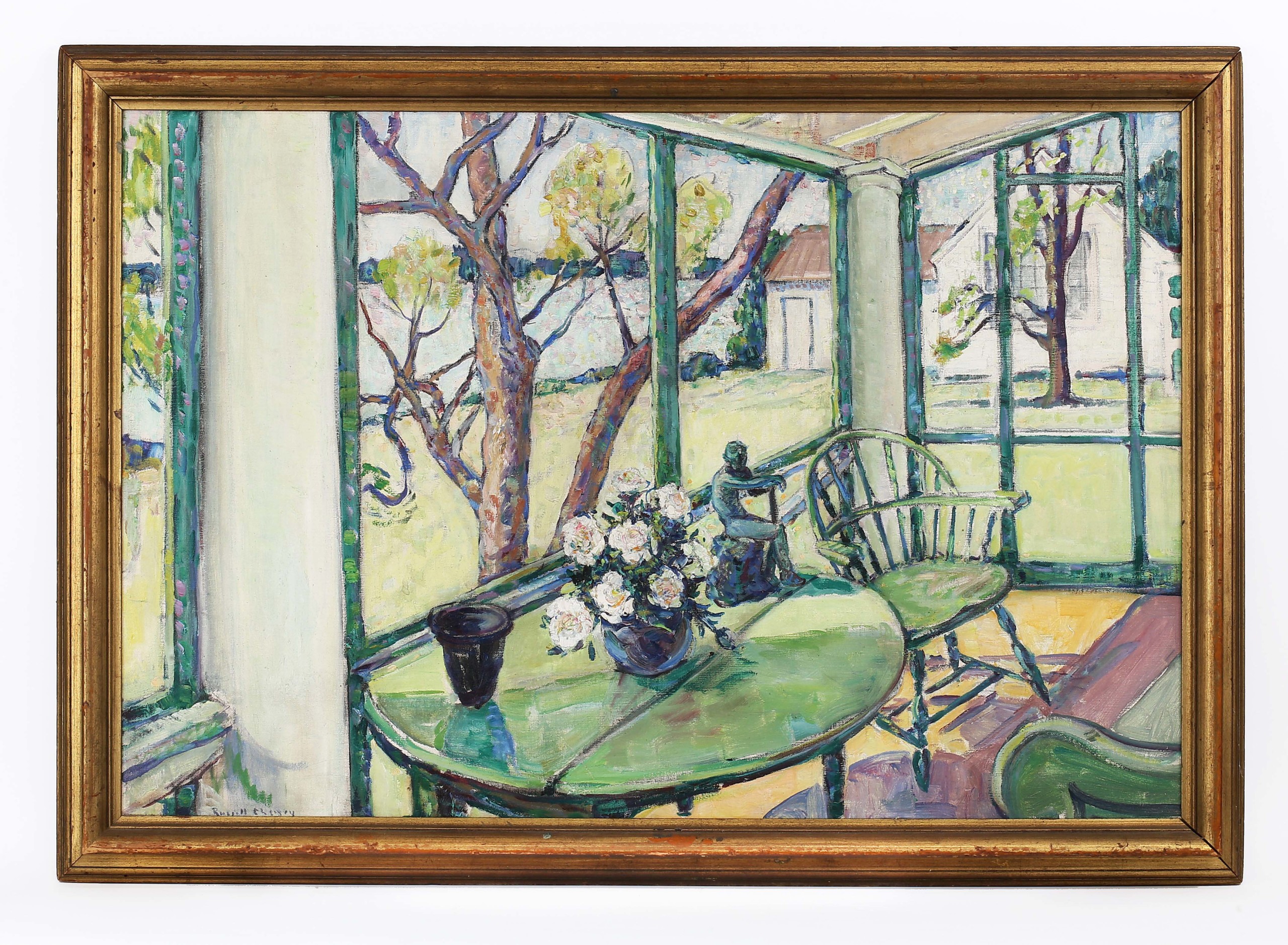

“Cineraria Plant/Cinerarias ‘From the Studio Window’” by Russell Cheney, 1937 (1938), 27 by 40 inches. Robert S. Chase and Richard M. Candee Revocable Trust.

By Kristin Nord

OGUNQUIT, MAINE — An exhibition of works by Russell Cheney at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, “Domestic Modernism: Russell Cheney and Mid-Century American Painting,” reframes and reasserts Cheney’s work within Midcentury Modernism in the United States.

Cheney was born on October 16, 1881, at home in south Manchester, Conn., approximately 10 miles east of Hartford, Conn., all but a company town for the illustrious Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company. The youngest of 11 children, he grew up in a 45-room mansion atop a hill overlooking the Cheney Silk Manufacturing Company mills.

The Cheneys had enjoyed great success initially as Connecticut clockmakers and later, as silk manufacturers, applying their hard work, inventiveness and business acumen to what had become a multi-generational venture. By 1860, the company employed 600; by 1920, 4,670 workers, or a quarter of the town, and their sales were $23 million (in 2021, that figure would equate to $368 million).

As early as 1872, the popular press (Harper’s New Monthly) described Manchester as a “workers’ utopia.” Eighteen years later, Harper’s Weekly, in its February 1, 1890, issue, reported, “At South Manchester, in Connecticut, there is what, in many respects, is the most attractive mill village in the country, one of the most delightful villages in New England.”

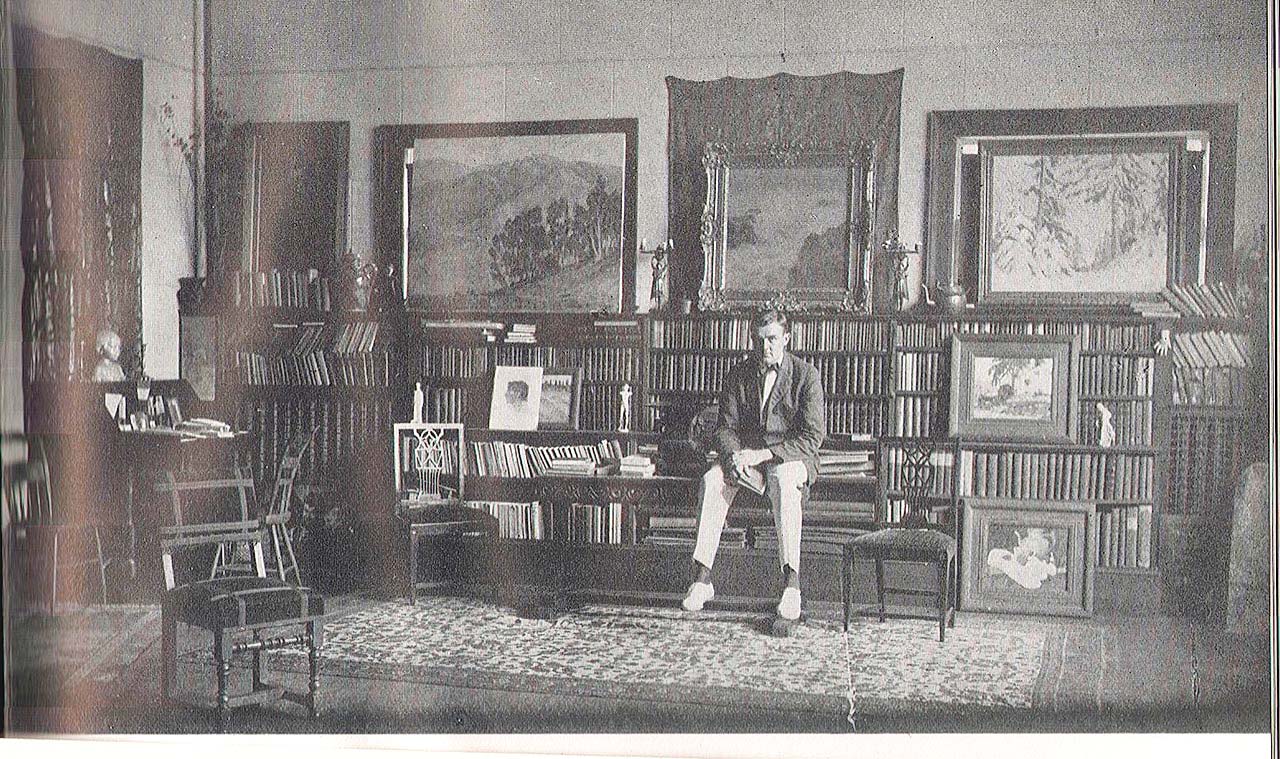

Cheney Studio, South Manchester, Conn., circa 1916-18. Russell Cheney Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

“So, it went without saying,” historian Scott Bane writes, “That being a Cheney would be an integral part of Russell’s personality. At the same time, if the family personified Yankee virtues of ingenuity, practicality and doggedness, it was also tribal.”

It’s notable that Cheney lived and worked in the family mansion, with an expansive studio, until he was 48. In this milieu, the youngest in the family challenged convention, receiving tolerant support for being an artist, and as time went on, less support for his sexual orientation.

“The family supported Russell’s choice of an alternative career. There were other artists in the previous generation; moreover, there was always a design aspect to Cheney silk enterprise, so art was not entirely foreign to them. I think that helped. But they suspected that Russell was not cut out to play a major role in the business,” Kevin D. Murphy, PhD, the exhibition curator and editor of the newly minted catalog, commented.

Initially, Cheney studied art with Walter Griffin in Hartford. After graduating from Yale University, he continued with classes at the Art Students League in New York, where he studied with William Merritt Chase, Kenyon Cox and George Bridgman, and at the Académie Julian in Paris. He also studied with Charles Woodbury, who was behind the emergence of Ogunquit, Maine, as a summer arts colony and who encouraged Cheney to paint outdoors in all weather and to “loosen” his style. Woodbury additionally shaped Cheney’s ideas by encouraging him “to envision the picture he was to paint before he began.”

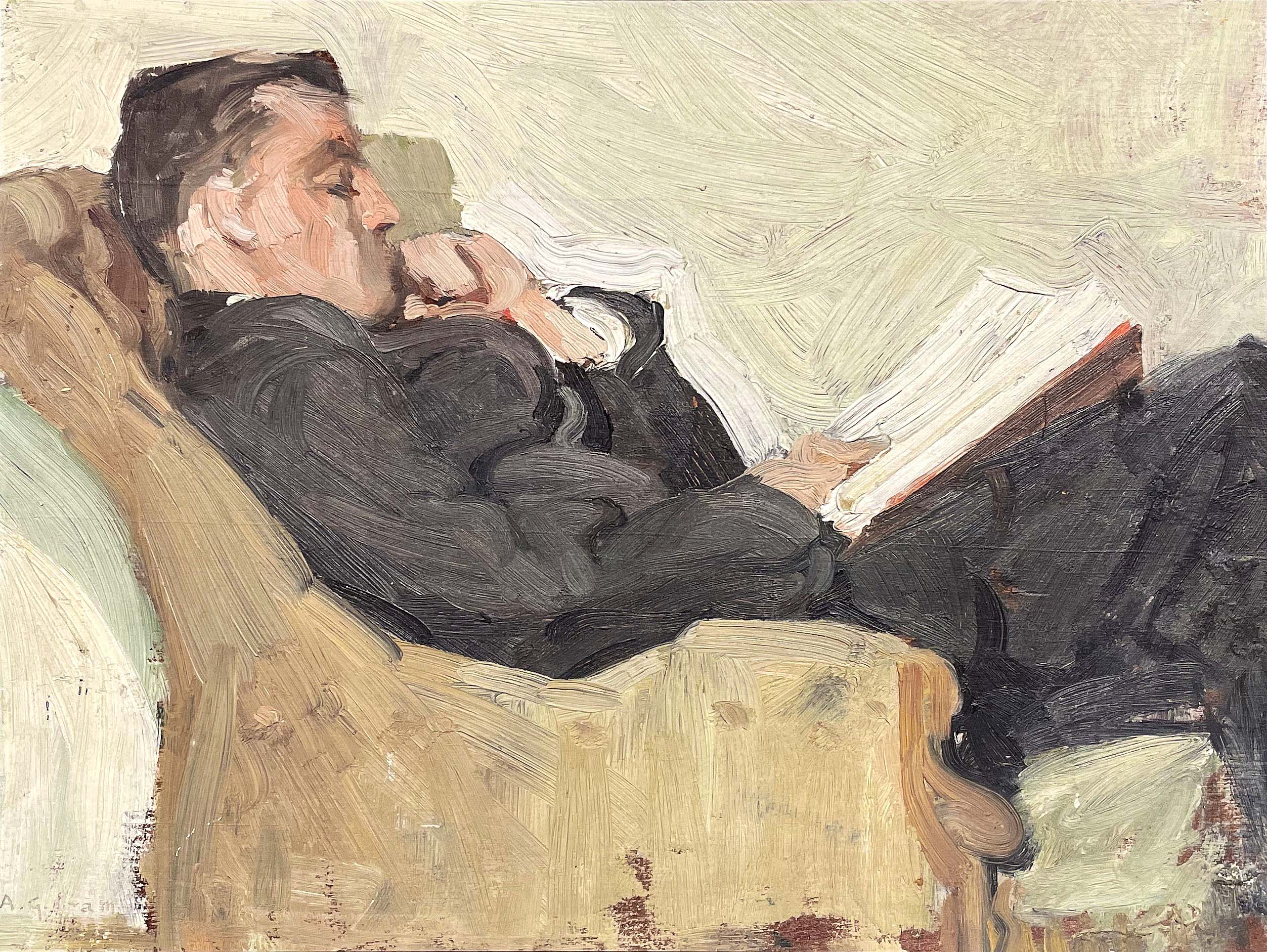

“F.O. Matthiessen on Balcony” by Russell Cheney, 1926, 36 by 29 inches. Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift from Barney and Lucy Bowron, Minneapolis, on the occasion of Harvard University’s 350th anniversary, 1986, H848.

On a 1924 voyage aboard the ocean liner Paris, Cheney met F.O. Matthiessen, a brilliant young man 20 years his junior. Matthiessen was credited with establishing American Studies as a discipline during his years at Harvard University and, in 1941, would produce his masterwork, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman. Their love affair turned into a serious long-term relationship, and the couple eventually settled in a home in Kittery Point, Maine. The two flourished for a decade symbiotically, with Cheney living or practicing much of what Matthiessen was considering intellectually. “How thrilling this must have been for Matthiessen to be so close to someone who brought his ideas to life,” Bane writes.

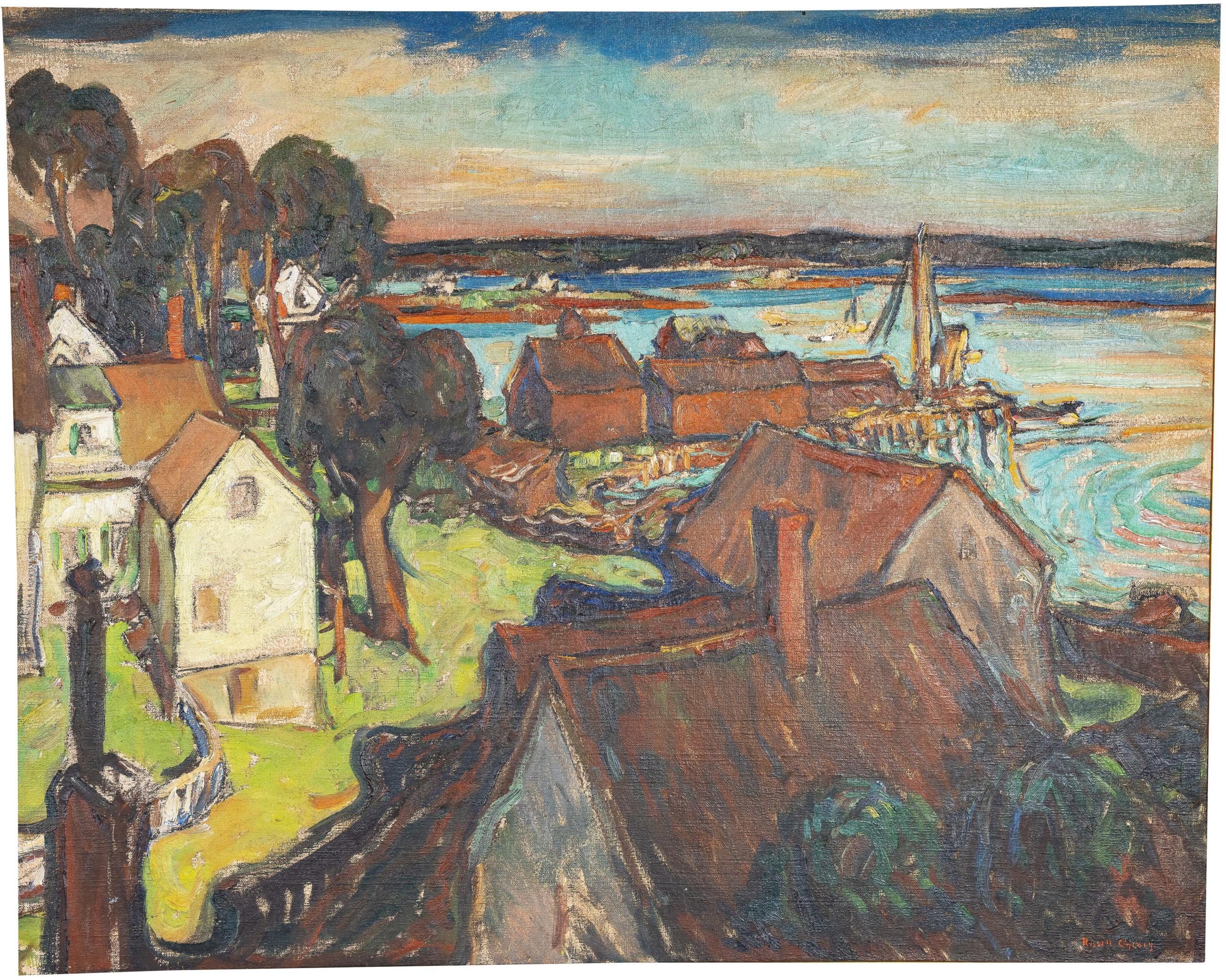

Eventually, the art historian Richard M. Candee writes, “Cheney developed a singular form of modernism based on the visual culture of New England, especially Maine. In his very best work he combined European avant-garde concepts with vernacular inspiration, and his paintings were rooted in a sense of place.”

As for his subjects, there were the prominent workers to whom he sometimes conveys sexualized and mythic status and domestic interiors that hinted lives behind their curtained windows. There are back streets and crowded neighborhoods, with the houses situated cheek by jowl. Cheney would produce 123 regional paintings of land, water and buildings and 45 interiors in all.

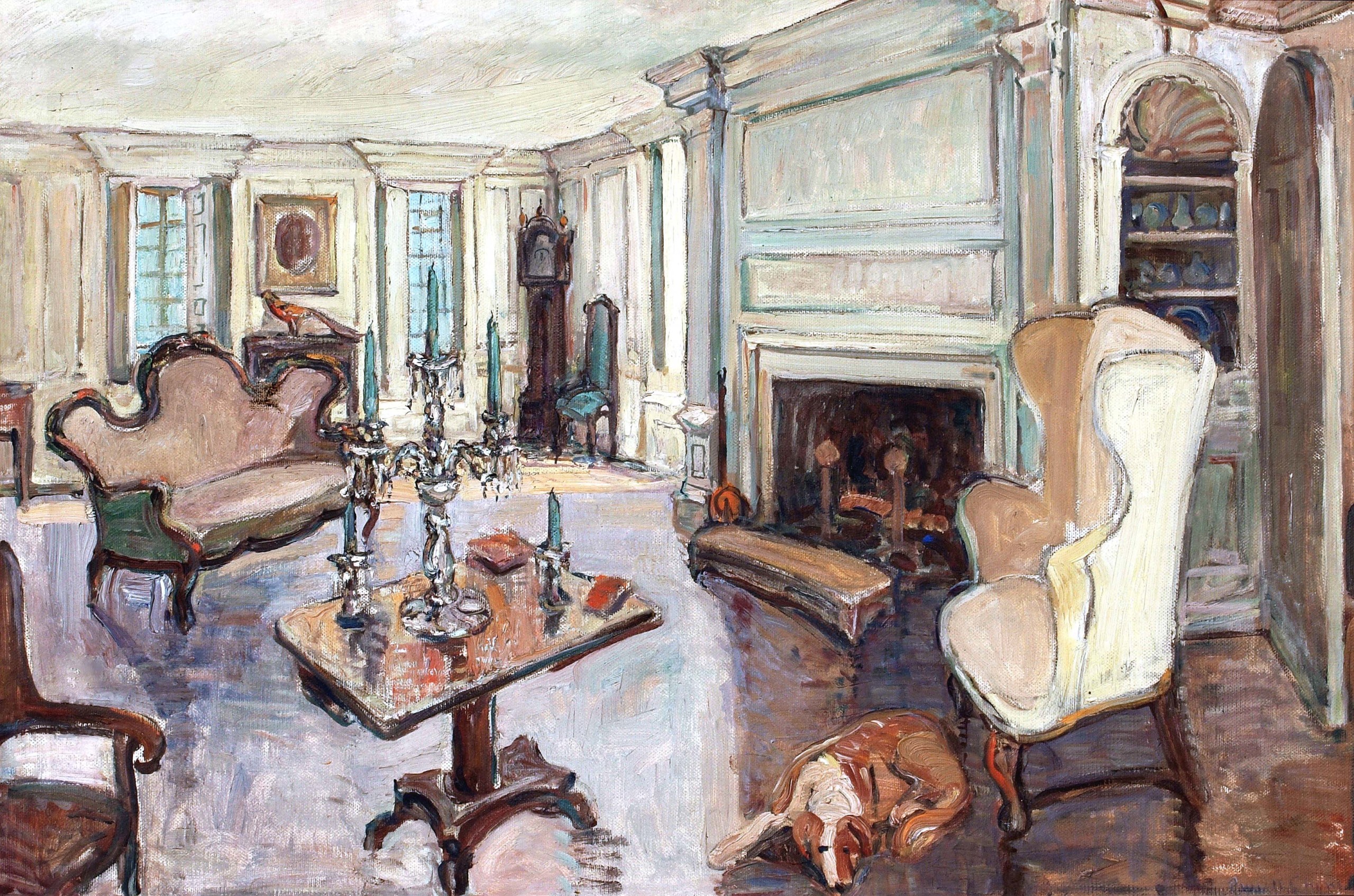

“Sparhawk Hall, Kittery Point” by Russell Cheney, 1930s, 24 by 36 inches. Private collection.

Murphy said recently that he hopes viewers “will come away with a few different ideas to think about. First, I would like them to see that being a ‘modern’ artist could mean a number of different things in the period from the 1920s through the 1940s. The critics at the time saw Cheney’s work as modern, just like (Marsden) Hartley’s, although it is not understood as such now because our definition of Modernism has been narrow. Other scholars have argued that art that was domestically scaled and themed was considered suspect because its connection with the home associated it with women’s sphere (given the sexist views of culture, it was not seen as serious or important).

“Second, I would like viewers to grasp that Cheney’s work was the product of his engagement of the domestic in two senses: it was produced in the context of his domestic life with Matthiessen and it took as its subject domestic themes, both actual homes and the domestic (US) landscape and built environment.”

“Third I would like to have viewers think about the subtle ways in which his paintings register his status as a gay man at a conservative cultural and political moment. They seem in many cases to register feelings of isolation and exclusion.

“Still Life with Flowers” by Russell Cheney, n.d., oil on canvas, 28-7⁄8 by 2-7⁄8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Hermann W. Williams, Jr, 1970.174.

“As one moves through the galleries, one will also be tempted to consider a number of ‘might have beens.’ As a sickly child, Cheney had suffered all of this life from asthma, when he and a number of his siblings contracted tuberculosis, his adult life was interrupted for months, and in one case, years, for treatment in sanitariums.

“As we learned with Covid, wealth doesn’t necessarily protect you from every possible illness. Tuberculosis was rampant until the invention of penicillin in 1928 and I am not sure how widely available it was at that point. His illness definitely had an impact on him in that there were substantial periods in which his travels — hence his subjects — were very limited, as was his stamina,” Murphy said.

And then there was the elephant in the room: his alcoholism, which, by the 1940s, was damaging his relationship with Matthiessen. His drinking binges had mushroomed into terrifying episodes, leading, in turn, to further hospitalizations. What now seem like, draconian treatments did little to alter the course of the disease and he died from it in 1945 at the age of 63.

In later years, Matthiessen would make it his mission to garner artistic recognition for Cheney, but, to some extent, the art world had moved on. And Matthiessen, himself, troubled by what observers now believe was bipolar disorder, took his own life in 1950. This was at the height of what was called the “Lavender Scare,” when an official US crackdown pushed the country’s gay population even further to the margins of society.

“F.O. Matthiessen with Pansy Littlefield” by Russell Cheney, 1926, 24½ by 30 inches. Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift from Barney and Lucy Bowron, Minneapolis, on the occasion of Harvard University’s 350th anniversary, 1986.

Viewers will be fascinated by Cheney’s portraits, landscapes and seascapes, whether it is the 1928 view at Kittery Point, an icy blue sea or depictions of his lover in scholarly attire. Many may nod in recognition when they encounter Portsmouth’s barbershop, which was famous for its clientele and a seat of daily exchange. Then there are the back streets of the city with their angled roof lines reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s Gloucester, Mass., watercolors. In portraits of working-class men — Kenneth Hill (1937) and Howard Lathrop (1937) — he merges to great effect realism, impressionism and abstraction.

Whereas Marsden Hartley set out to be seen as Maine’s premier painter, Cheney was interested in painting what he sensed and felt more than what he actually saw. His scenes often harbor ambiguous messages, with stately interiors presented off-kilter upon close notice and his working men charged with sensual appeal. There is the disquieting interior at Sparhawk House, in which Cheney appears to challenge the trope of the measured life within a stately Colonial. There is Depot Square, a visual embodiment of The Great Depression. His snow scenes, which many critics have said are the best of his oeuvre, exude the light and harsh tranquility of this special time in the New England calendar year. He draws our eyes to the beauty up close, whether it is the geraniums on the windowsill or cinerarias featured in “From the Studio Windows” (1937).

“In the Studio” by Russell Cheney, 1941, oil on canvas, 23 by 27 inches. Collection of the Robert S. Chase and Richard M. Candee Revocable Trust.

“Yet upon reflection, viewers may also see in his vision the marginalization that happened to him as a person,” Murphy said. “The oblique perspectives, the hints of a domestic life that is never shown, the walls that exclude the viewer’s sight-line — these suggest how structures, buildings and places of work can marginalize and exclude the outsider. Who can go where? Who can be shown? Who’s excluded?”

In “Piscataqua River / Winter Trees” (1931), a small grove of twisted trees are locked in a dance while the wintry world sleeps. One can’t help but think of Cheney and Mattheissen and where their partnership would lead them.

“Domestic Modernism: Russell Cheney and Mid-Century American Painting” will be on view at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art through November 17.

The Ogunquit Museum of American Art is at 543 Shore Road. For more information, 207-646-4909 or www.ogunquitmuseum.org.