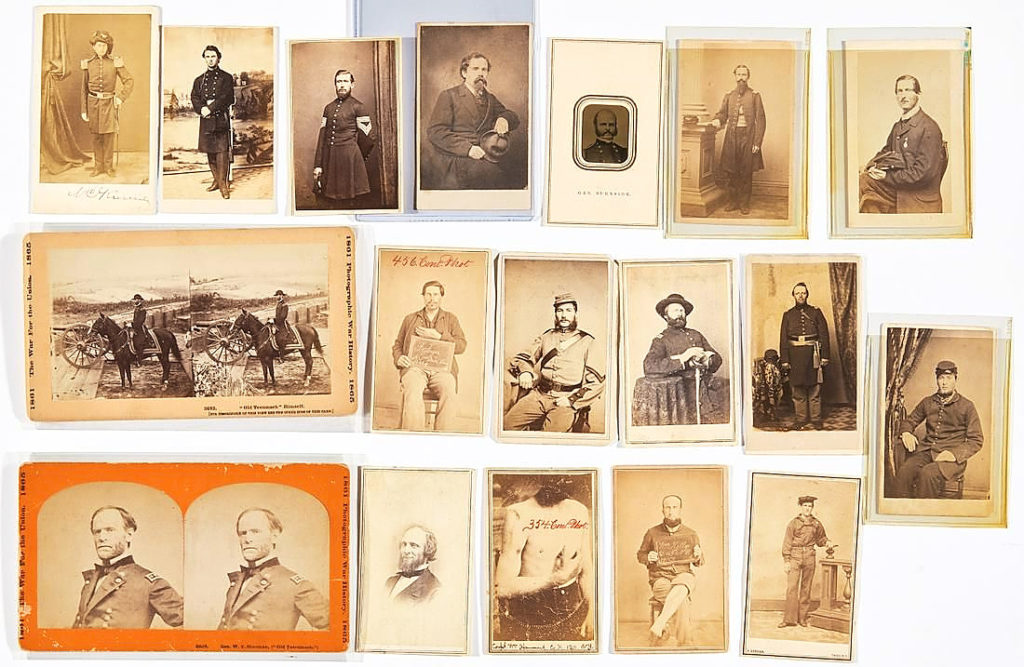

Bringing the highest price of the day at $10,000, was this lot with 42 Civil War photographs. Most of the subjects were identified and many were doctors and surgeons.

Review by Rick Russack, Photos Courtesy New England Auctions

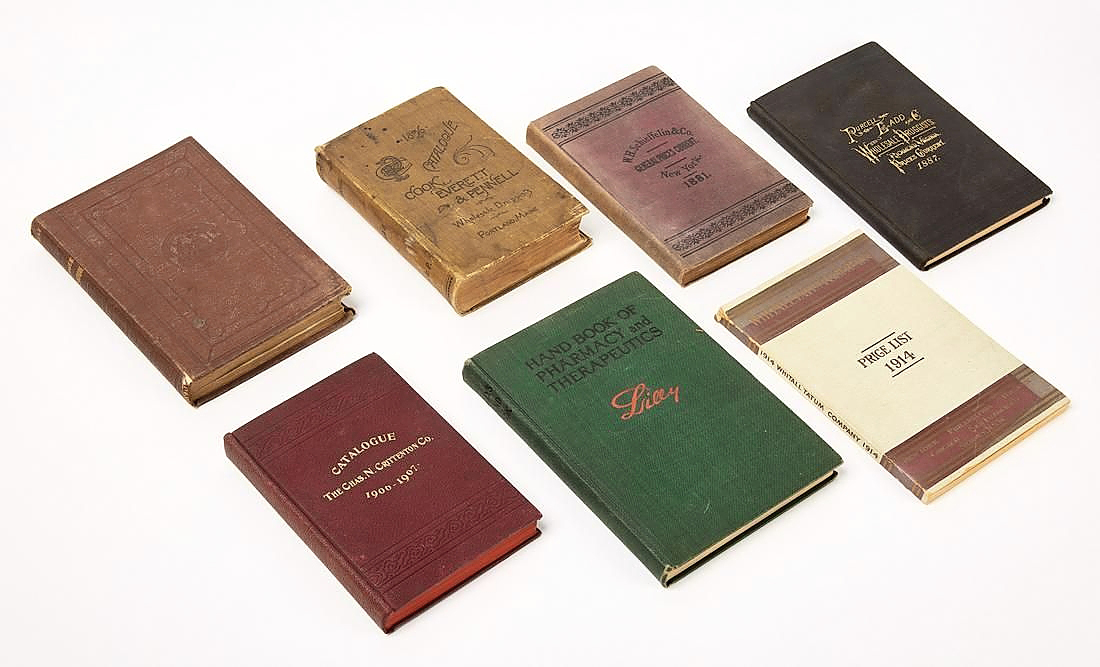

BRANFORD, CONN. — Some of the more unusual items Antiques and The Arts Weekly has reviewed recently were sold on March 8, at Fred Giampietro’s New England Auctions (NEA), when it sold the first half of the Meloni collection which had been decades in the making. Interestingly, given the nature of the collection, one might assume that the collector was in the medical field but that was not the case. Included were human skulls, Nineteenth Century cased sets of dental and medical instruments such as amputation instruments, cases of glass eyes, and seldom-seen early scientific devices. There were also groups of photographs; many of these were unusual and the word “gruesome” could be applied to some. There was a large collection of medals, many with a medical theme. There were also historical and rare books, a collection of medical, dental and pharmaceutical trade catalogs, early medical and other photographs, medals, walking sticks and related items. But perhaps the most unusual items were two Nineteenth Century vampire killing kits.

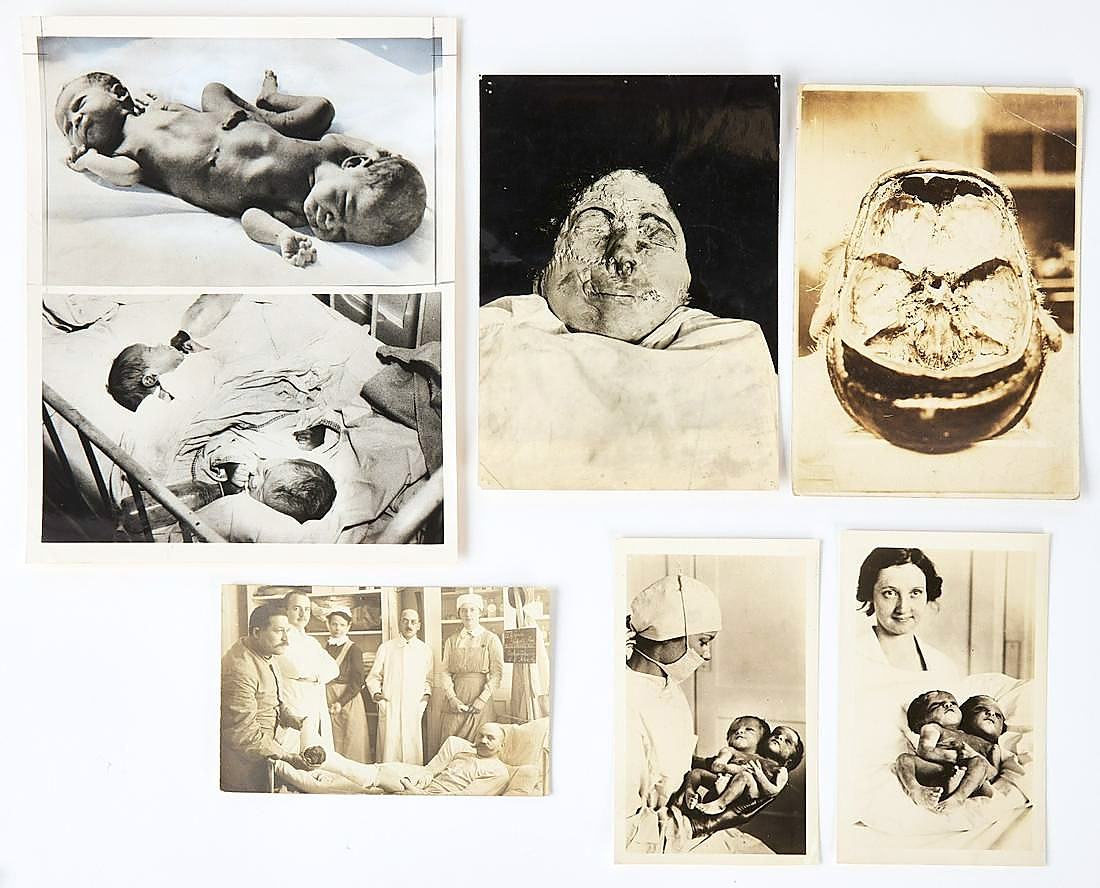

Prior to the sale, Giampietro said that there had been a lot of interest in the Civil War and medical photographs, some of which included morbid medical subjects. The interest translated to dollars and it was a lot of 42 Civil War photographs, predominantly cartes de visites (CDVs) and mostly identified, that brought the highest price of the day: $10,000. Many of the subjects were doctors, surgeons and wounded soldiers. Included was a tintype of General Ambrose Burnside and two stereoview photos of General William Tecumseh Sherman. One lot of 25 photos that showed medical abnormalities and deformities realized $938. These were well identified with one photo showing a man with four prosthetic devices, another with grossly deformed feet, another of a woman with three breasts and others. A lot of 71 photos including 14 of dead bodies, some crime scene photos, an 8-by-10-inch photo of a horse-drawn ambulance, and several more, finished $750. Consider the time and effort that went into putting these collections together.

As previously mentioned, there were two cased vampire killing kits with all the necessary equipment. One kit, “Professor Blomberg’s Vampire Killing Kit,” in the original fitted case brought $3,750. It included a small pistol, silver bullets, an ivory cross, garlic and various other necessary equipment. The “Dr Blomberg” mentioned was not a real person and although the kits give the appearance of having been made in the Nineteenth Century, evidence exists to suggest that they were Twentieth Century creations, conceived of as hoaxes. Which does not mean they’re not collected. Jonathan Ferguson, the curator of firearms at the United Kingdom’s National Museum of Arms and Armour, wrote in a blog post, “Nowhere was there evidence to support real vampire slayers carting about one of these kits. It became clear that the ‘Blomberg’ kits, with their focus upon silver bullets, were very unlikely to have existed prior to about the 1930s at the earliest. Though constructed from antique boxes and contents, they were most likely not produced until the era of the classic Hammer vampire movies (second half of the Twentieth Century).” Another “Professor Blomberg” kit in the sale, with fewer “necessaries” brought $2,000.

The period when vampire killing kits were marketed is uncertain. Some say they were made in the Twentieth Century and the auction catalog makes it clear that the full background is not definitively known. Despite that, vampire kits have a loyal following and this one, with everything a vampire killer would need, sold for $3,750.

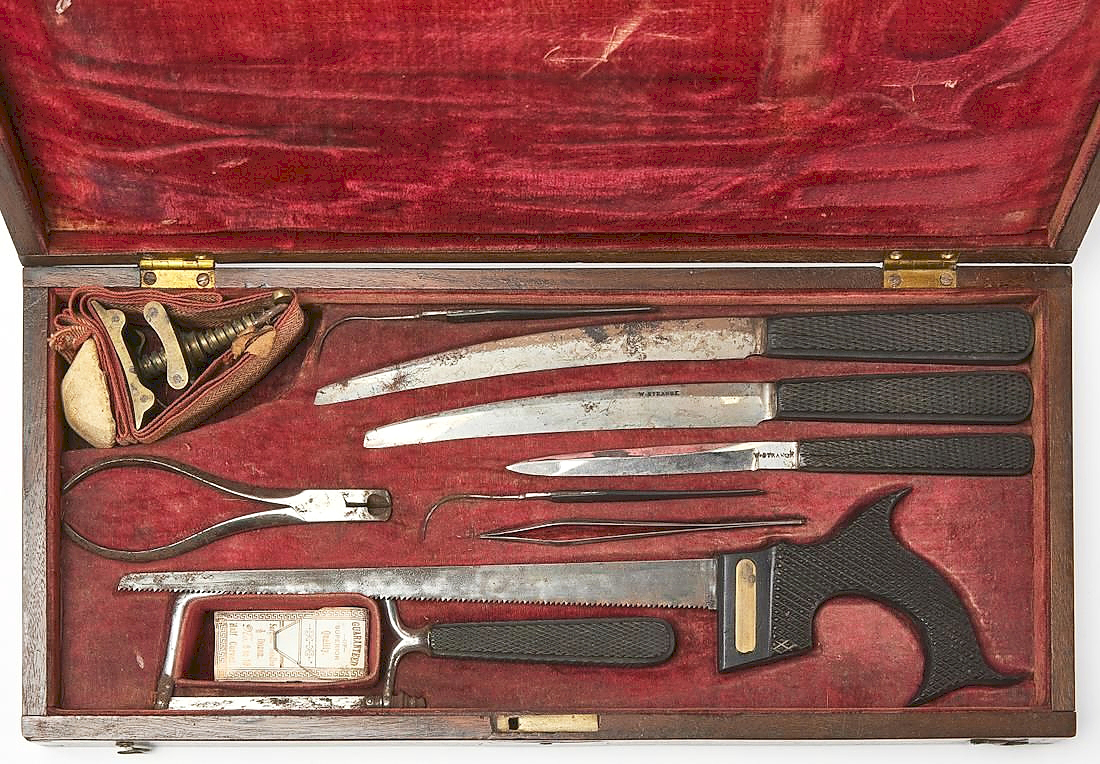

The strength of the sale was in the dozens of sets of medical and surgical tools, along with related books and ephemera. The selection was led by a lot with four human skulls. Three were complete; two were adult, while one was that of a child; the group earned $5,625. Collectors of amputation kits had several to choose from and the favorite was a circa 1830 kit by Wm Strange, London. In its original fitted case, it had two saws, about 10 other instruments and realized $4,375. A mid-Nineteenth Century set marked “Samson, Paris,” in a leather and brass case, with a saw and several other instruments, sold for $3,500. In all, there were more than two dozen amputation kits, including a circa 1850 Civil War-era surgeon’s field set which sold for $1,500. It was marked “Weiss London” and cataloged as incomplete and with replacements. The instruments in these sets were a vivid reminder of the state of medical care in the Nineteenth Century.

There were sets for other specialties. A mid-Nineteenth Century cased obstetrical set in a brass-bound mahogany box, by Mackenzie, Edinburgh, sold for $3,750. There were several other lots of obstetrical instruments, as well as a Twentieth Century teaching device known as a Stander Phantom Obstetrics Aid which earned $875. The other obstetrical offerings included a copy of the Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Science and Practice of Obstetrics by F.H. Getchel, published in Philadelphia in 1885. The leather spine was missing, and it brought $188.

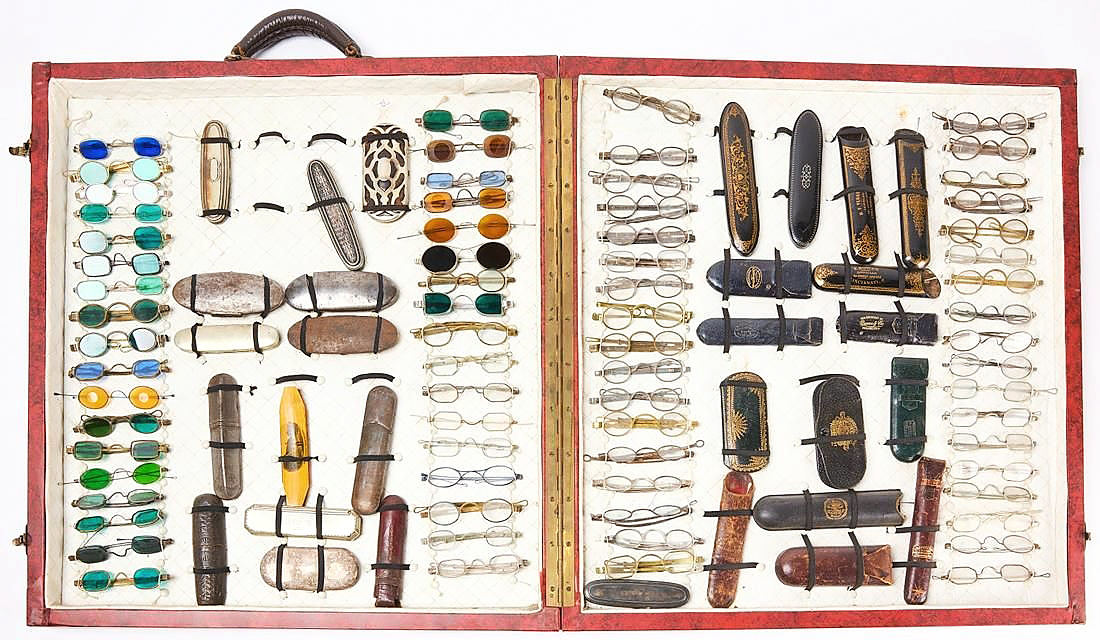

The practice of fitting artificial eyes goes back to the Egyptians; a Prothese Oculaire set, used to fit glass eyes, sold for $3,250. The mahogany and brass case had several compartments, instructions in French, with dozens of glass eyes.

The second highest price of the sale, $5,625, was earned by this group of human

skulls, one of which belonged to a child. Three were complete while one was not.

A lot with 16 hearing aids realized $2,875. A circa 1850 trepanning set labeled “Charriere” sold for $2,500. These were used to drill round holes in the skull so pressure could be released, or other treatments administered. An unusual device called a compass, used to locate projectiles such as bullets in the body earned $1,375. There were about a dozen items in the set, some of which could also be used to extract bullets from the body.

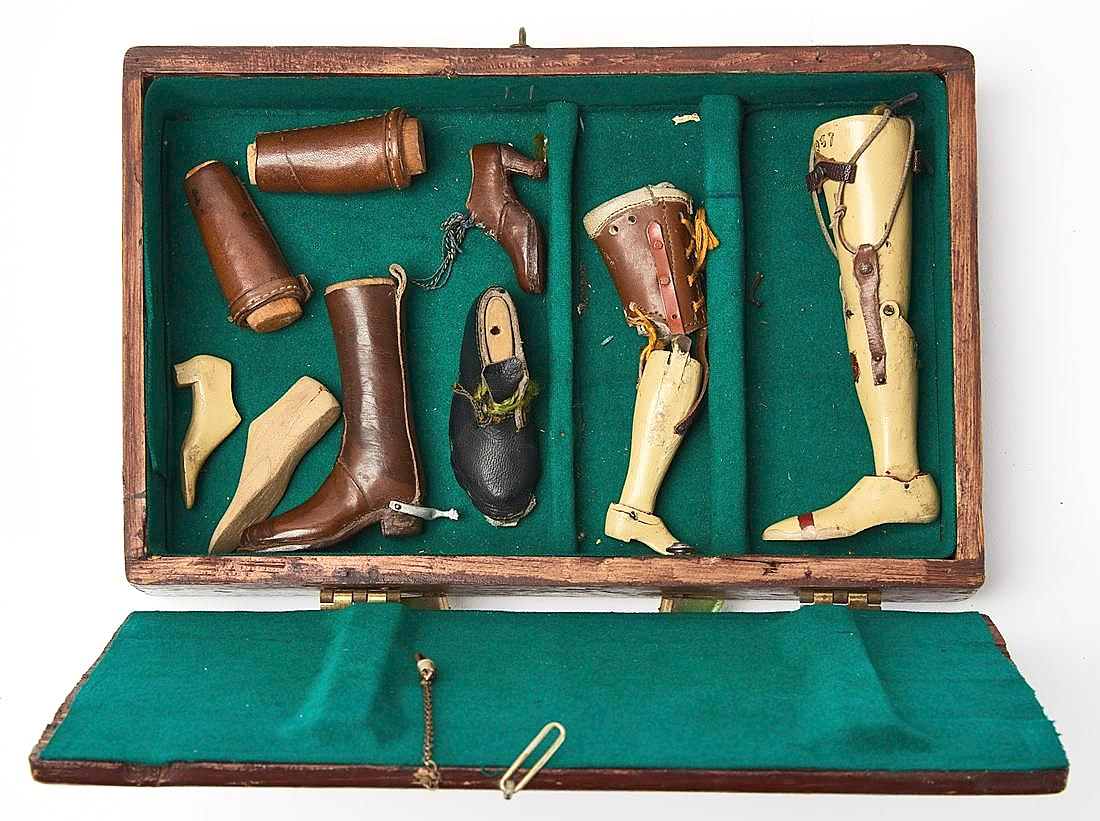

Other medical devices included early microscopes and a range of dental equipment. There were traveling medical kits, a collection of bloodletting devices; a large collection of early hearing devices; arm and leg prosthetics; medical teaching aids and advertising.

John Kuenzig, a dealer specializing in science and technology, and books about those specialties, commented before the sale, “There’s some really unusual stuff in this sale. If I had to pick one item, it would be the Dr Fleet’s Spinal Demonstrator. This was really great.” The circa 1938 device was a flexible metal spine used in training chiropractors. It was 35 inches long, mounted so as to be hung on the wall, and sold for $2,500. Kuenzig also liked the Cambridge and Paul polygraph, saying, “These are popular with collectors and early ones like this don’t appear often.” Contrary to today’s usage of the word “polygraph,” this was a diagnostic instrument used in the treatment of cardiovascular conditions, not a lie detector. It included its original instructions and reached $313.

Numerous dental tools were included in this doll-house-form storage cabinet. Made by the American Cabinet Co circa 1925, only about 125 were produced. It was probably used by a dentist treating children and realized $2,375.

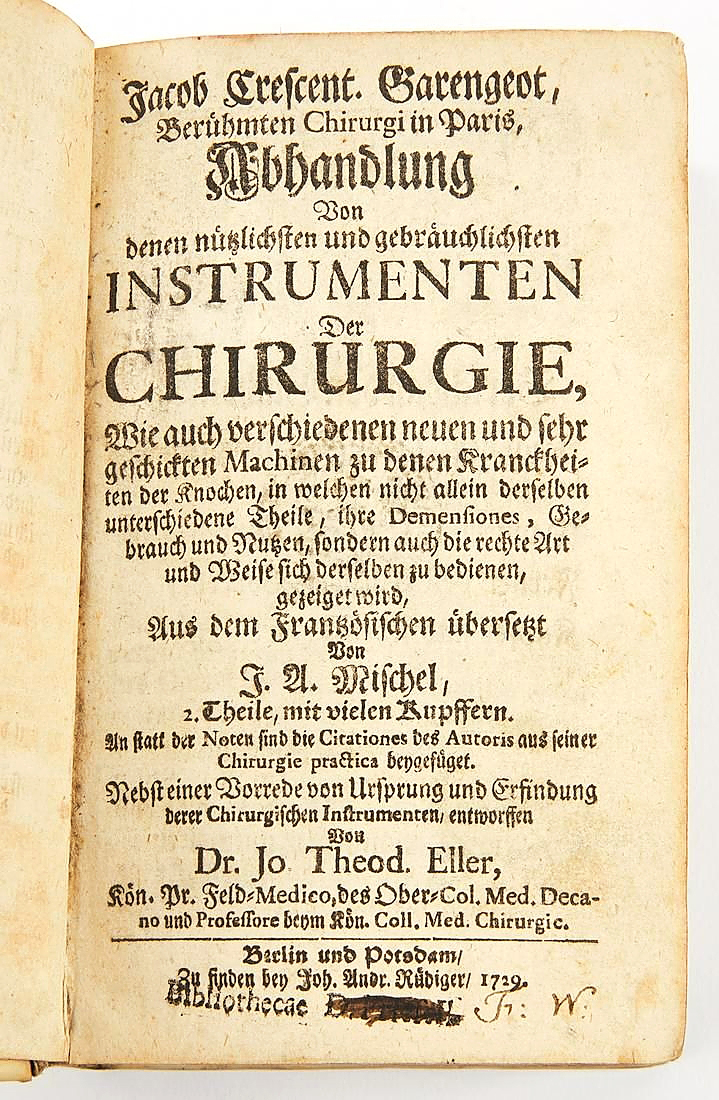

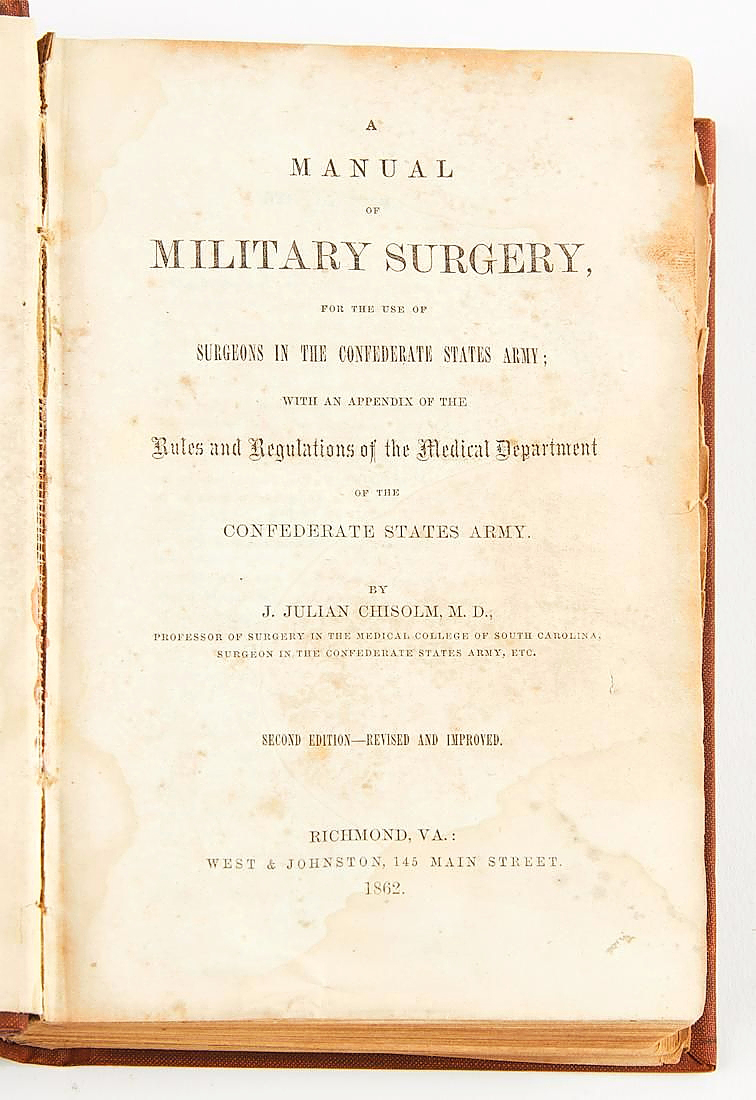

The Meloni collection included several early medical books, the earliest being a 1661 study, Cirugia Universale et Perfetta, which was written by Giovanni Andrea Della Croce, and included numerous plates. It was published in Venice and earned $563. Several Eighteenth Century tomes were in the sale, many profusely illustrated. Another book, Nivis Usu Medico by Thomas Bartholini and published in 1661, with the first description of the human lymphatic system, earned $281. This first printing also contains the first known mention of refrigeration of anesthesia. A Manual of Military Surgery for the use of Surgeons in the Confederate States Army sold for $1,000. It had been published in Richmond, Va., in 1862.

Historical documents included a collection of 34 Civil War records and documents highlighted by a manuscript map in a contemporary hand, titled a “Map of the route marched by 5th Regt P.R.v.C.(?) starting in Falls Church, VA June 23, 1863 and arriving in Gettysburg ‘Battle fought’ July 1-2-3-1863. Manasses [sic] Gap ‘Battle fought’ and ends at Fayetteville, August 4, 1863.” The lot included several other documents with military subject matter and realized $2,125. A vellum document with masthead showing a ship and lighthouse, signed by President James Madison in 1809, granting safe passage to a ship, earned $1,188.

After the sale, Giampietro said, “This was a new field for us. It was a challenge and I wanted to do it because I knew I’d learn from the experience. We promoted the material heavily on social media to get the collection in front of the medical community and doctors. That worked as many of the buyers were, in fact, doctors. We found there was a lot of interest from European and South American buyers, and we had a lot of inquiries from folks interested in specific lots. We finished with about $300,000 and that was about 30 or 40 percent above estimates. It was just the first half of the collection, there will be more to come.”

New England Auctions’ next sale, in mid-April, will include the mocha ware collection of Jonathan Rickard, along with more things he collected, and the collection of Jeanine Dobbs, a well-known dealer and collector. For additional information, 475-234-5120 or www.neauction.com.