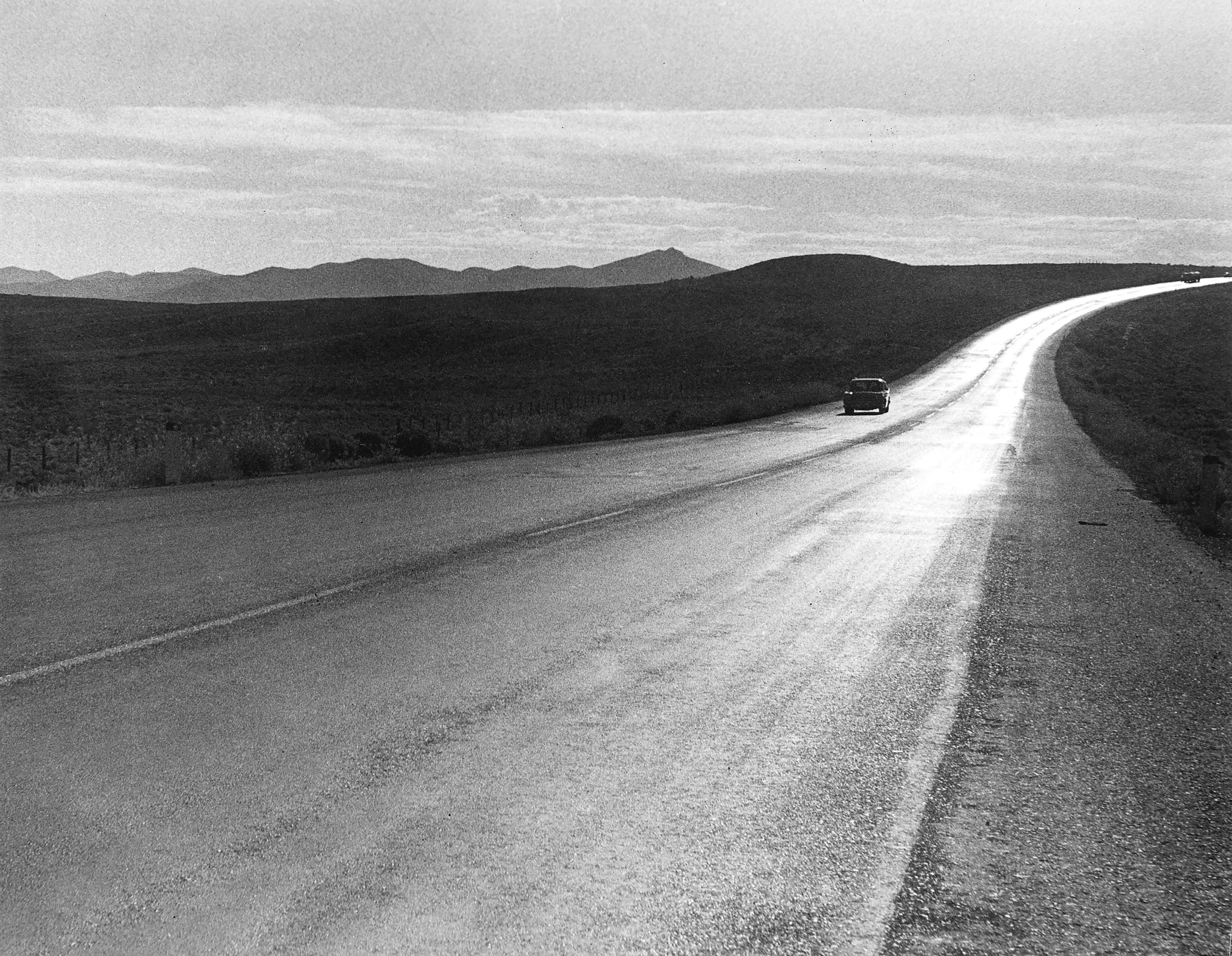

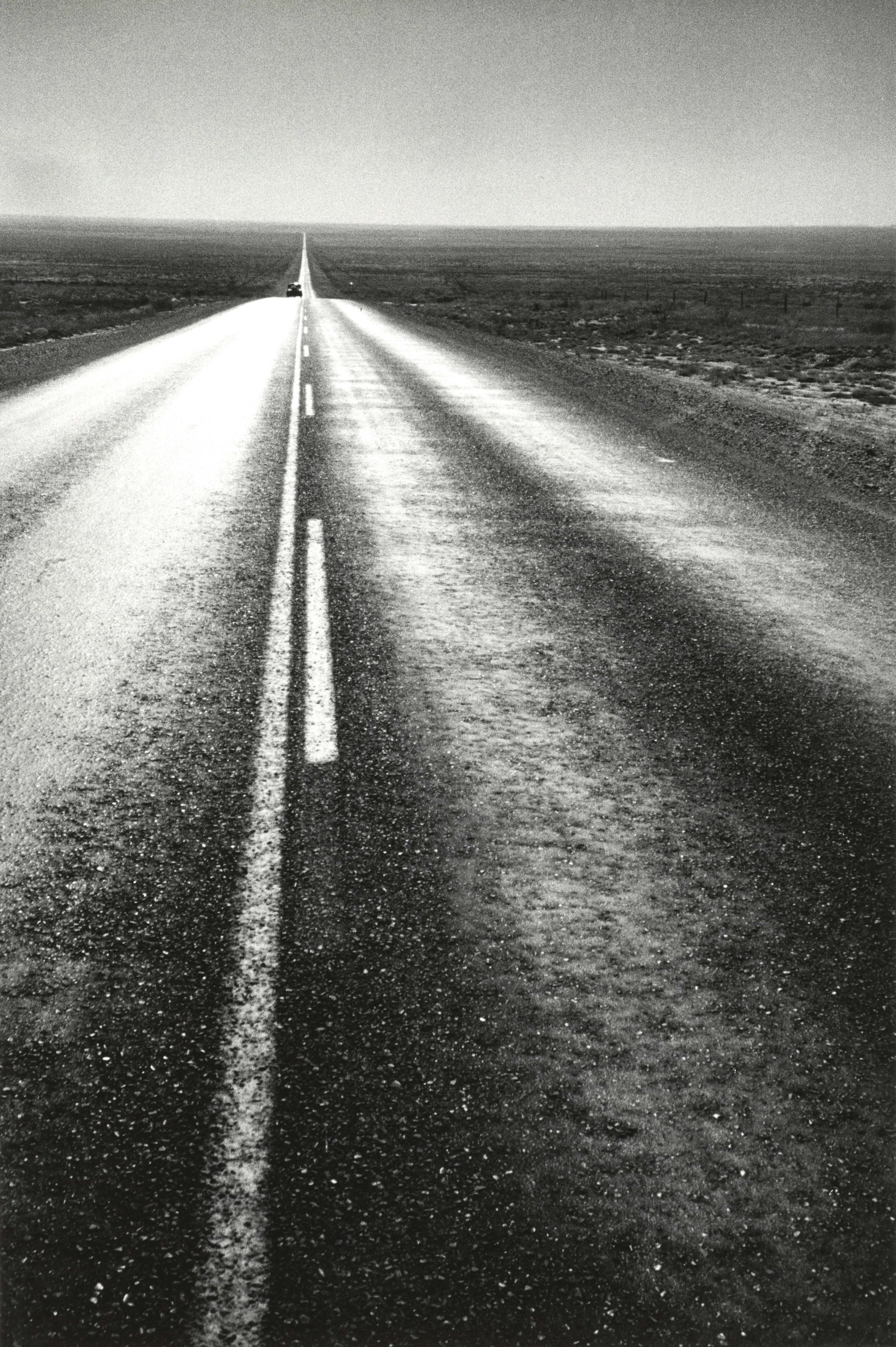

“Between Lovelock and Fernley, NV” by Todd Webb, 1956, printed 2023, inkjet print, courtesy of Todd Webb Archive. ©Todd Webb Archive.

By Kristin Nord

HOUSTON — In April of 1955 Todd Webb and Robert Frank set forth to capture life in America. One photographer would travel by car, the other, by foot, by boat and by bike. What they found on their separate journeys would have much to say about their confrontations with the nation’s complexities and its ever-evolving story. And each would struggle to reconcile what they found with what America purported to be.

Now, in “Robert Frank and Todd Webb: Across America,” which is on view through January 7 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, their revelations are being presented for the first time in tandem. The two were of different generations — Frank was just 30 and Webb was 49 — as distinct as the army field boots that Webb donned and the 1950 Ford Business Coupe that became Frank’s mode of transportation. Webb’s measured pace proved a perfect match for his large frame camera and his carefully composed images, whereas Frank’s 35mm Leica enabled him to pair movement with selective focus and to shoot frames as he often did from the window of his moving car.

Frank and Webb had secured identical grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation for their projects, but they were on their own missions. Each had had success in commercial photojournalism, but they now sought to stretch themselves as artists.

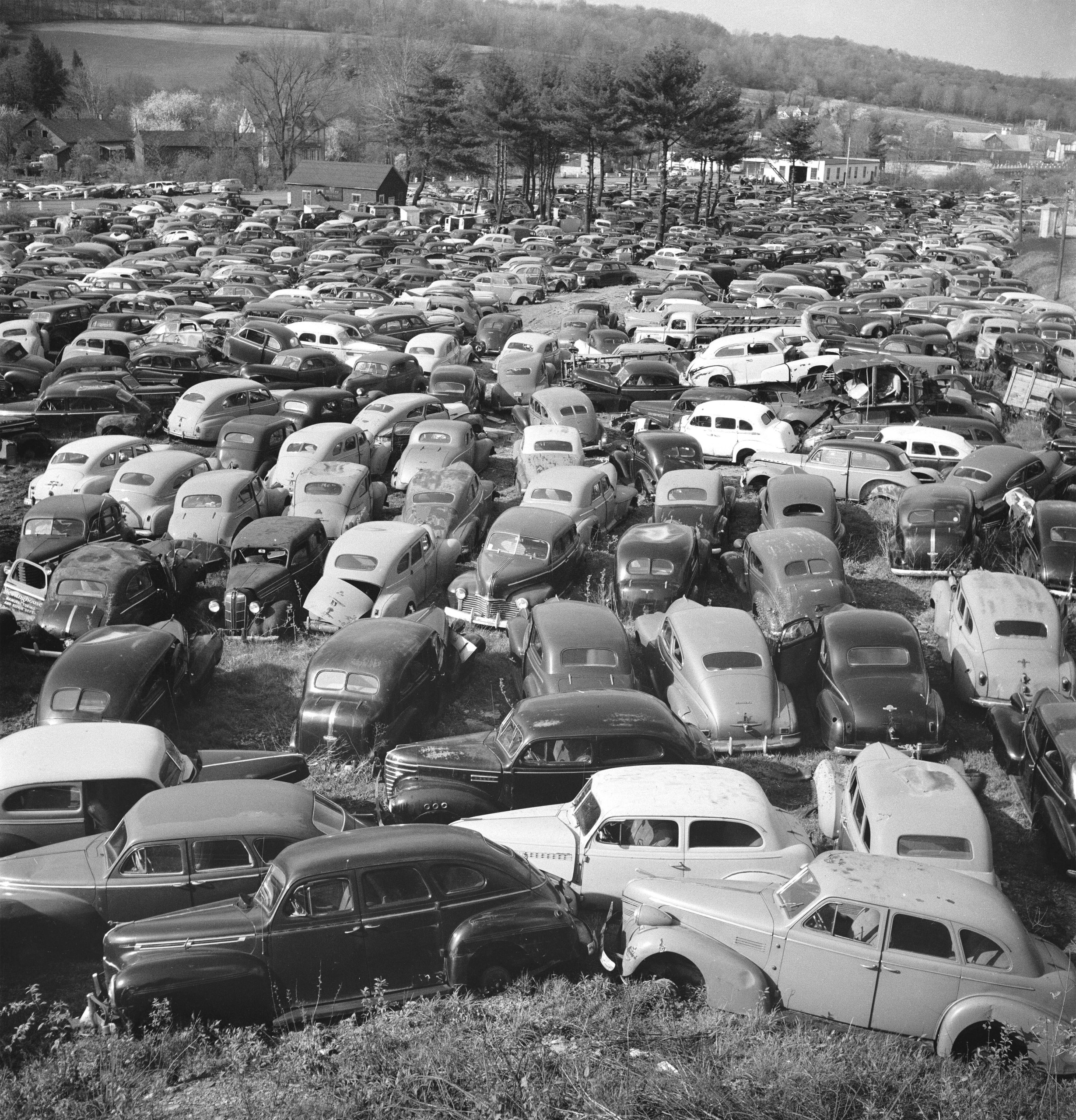

“Wrecked Car Lot, Staystown, PA,” 1955, printed 2023, inkjet print, courtesy of Todd Webb Archive. ©Todd Webb Archive.

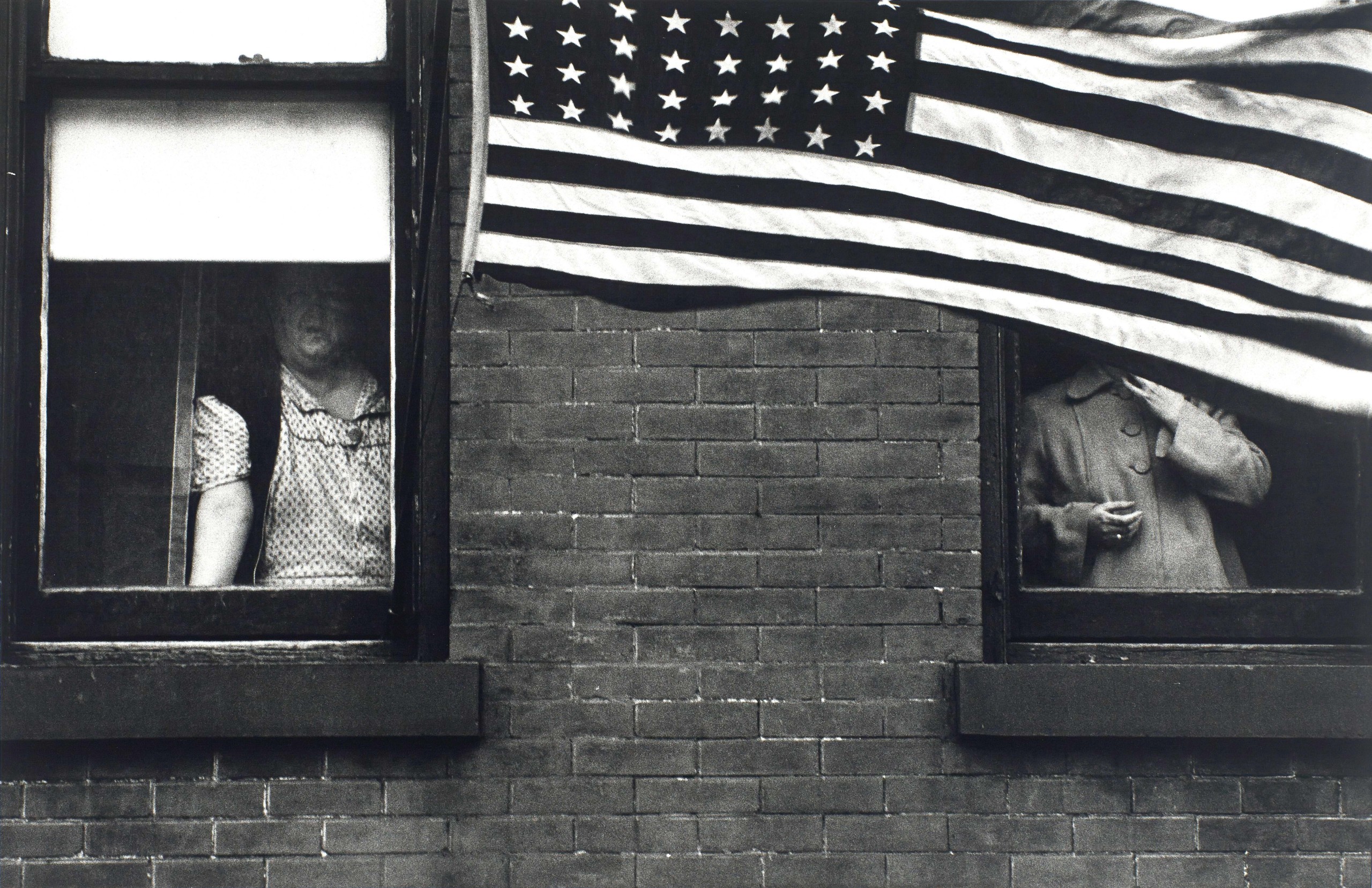

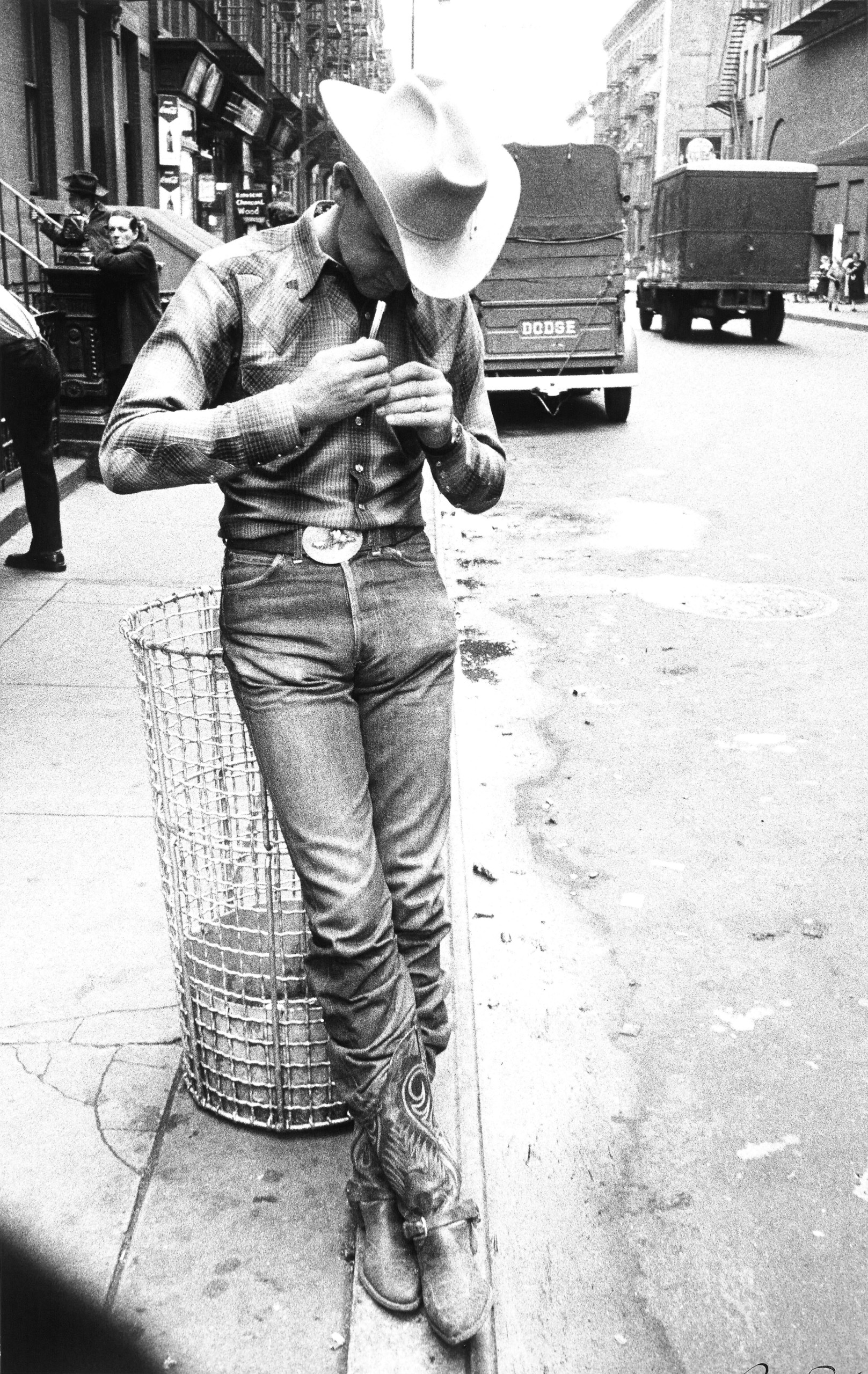

There was much to encounter: political rallies, cattle auctions and scenes from bars and coffee shops and diners. There were cowboys and workers on the Detroit auto assembly lines, gravesites and dumps, and men donning many hats. There was pageantry and American flags and the lure of the open road. And there were also signs, as Frank would note, that the consumer culture had arrived with a vengeance.

“Here it is, broken — used up — smashed to pieces — thrown away — left to rot. Mattresses, record players, TV sets, bottles, glasses, clothes, toys, furniture, automobiles, photographs, Art…more is produced than can possibly be consumed,” Frank wrote. Such raw confrontations had jolted his senses. “I was aware that I was living in a different world — that the world wasn’t as good as (the ideal image of America) — “It was a myth that the sky was blue and that all photographs were beautiful.”

Webb, an avowed optimist and believer in freedom and upward mobility, had begun his project with the plan to trace a direct line from the successes of the past to the advances of the moment. However, he soon reported sadly that the people he encountered “had jettisoned the past in their fervor for new and novel commodities.”

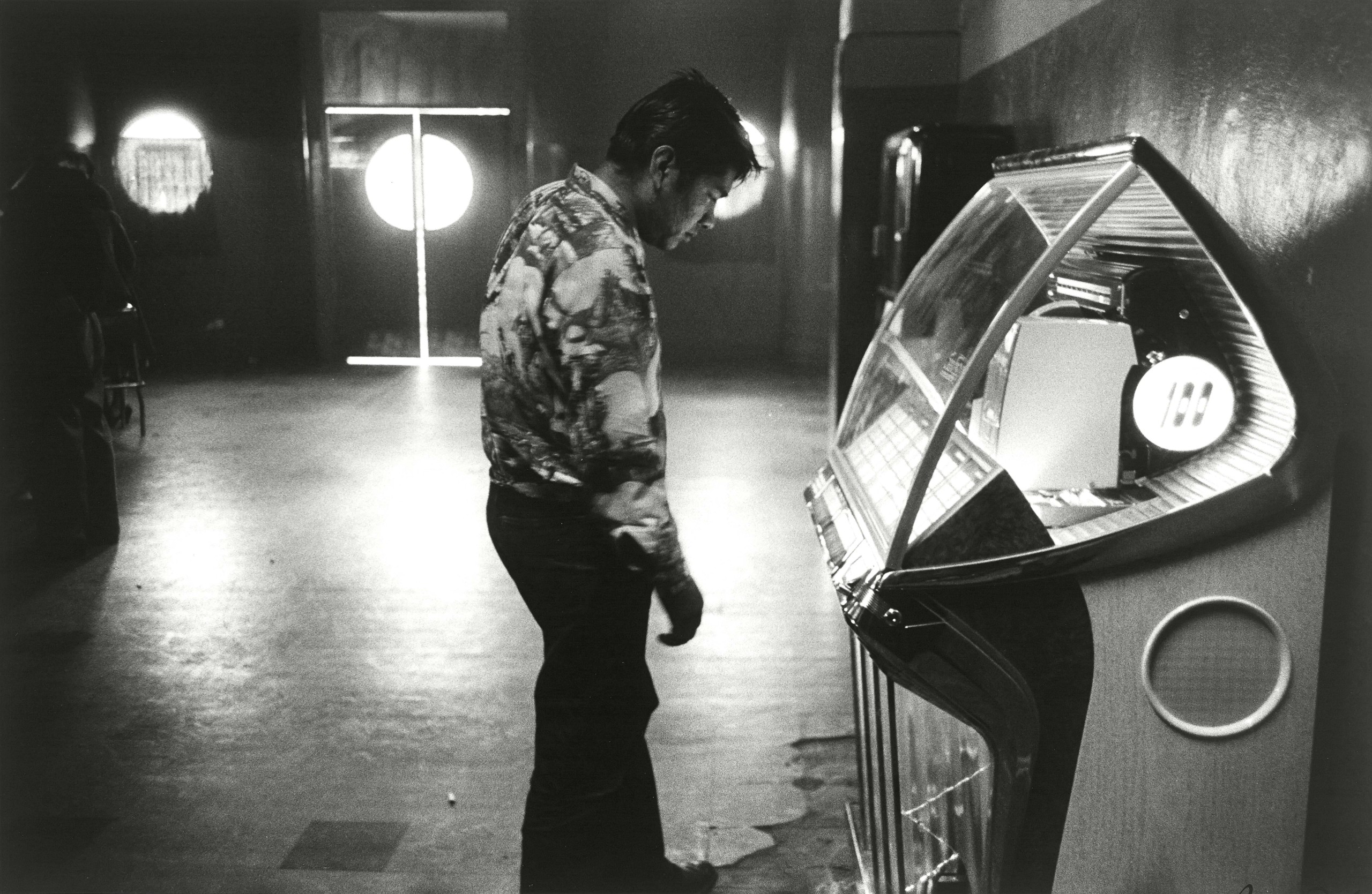

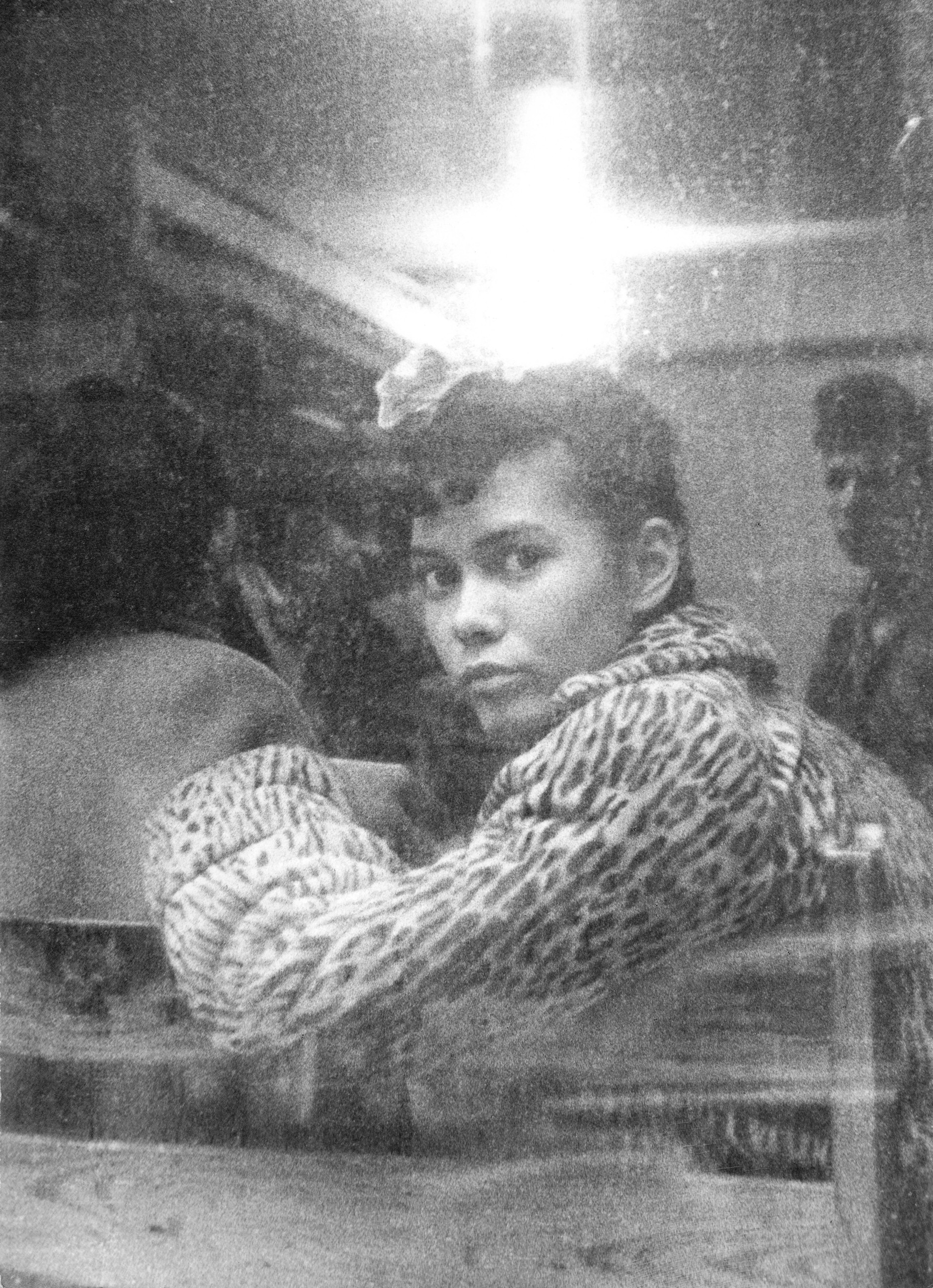

Untitled by Robert Frank, 1955-56, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation. ©The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation.

The Detroit native had come to photography through a circuitous route after his early success as a banker and stockbroker ended with the stock market crash of 1929. In the ensuing years, he prospected for gold and worked as a forester, a farmer and a writer. A job of delivering a car to the coast had whetted his appetite for travel, and a 10-day immersive workshop with Ansel Adams solidified his ambitions. “I was sunk, fell for it,” he reported. His work caught the notice of Alfred Stieglitz, who not only gave him cameras to use but approached Grace Mayer and convinced her to mount an exhibit of his work at the Museum of the City of New York.

By midcentury, he was at the top of his field. He’d been selected for the 1948 exhibition, “50 Photographs by 50 Photographers,” Edward Steichen’s photographic history; the 1952-53 “Diogenes with a Camera II,” in which his photographs had hung alongside works by Dorothea Lange, Man Ray, Ansel Adams and Aaron Siskind. He was among the photographers to contribute to the hugely popular touring show, “Family of Man.”

Additionally, his innate curiosity and amiable disposition opened doors and helped him make friends wherever he landed. Whether stopping for an Amish horse sale, or establishing an instant kinship with Clifton Ray Durham, a pilot captain on the Ohio River, “I seem to have a talent for meeting people, for liking people, and they respond,” he said.

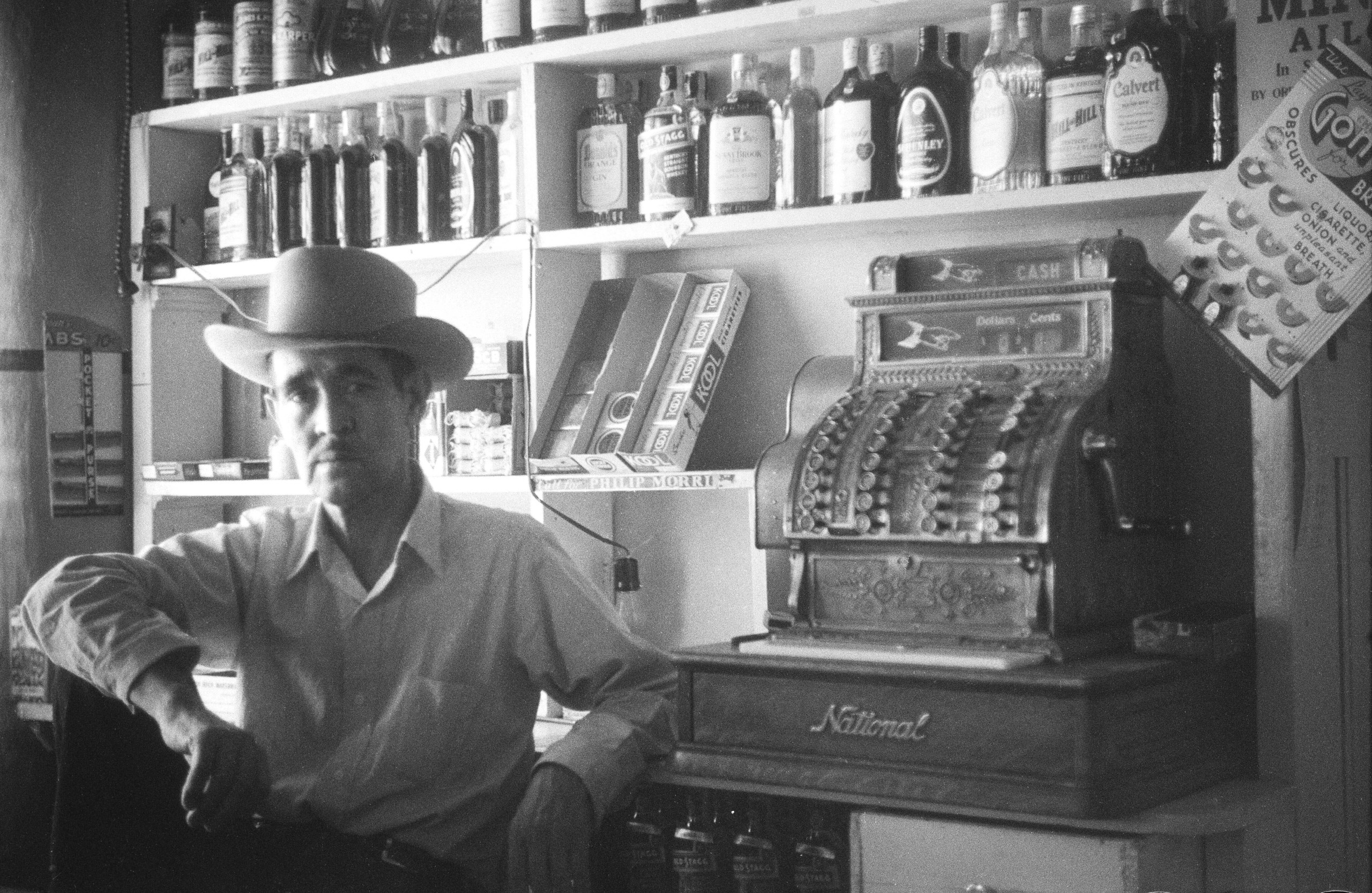

“Cowboy, Lexington, NE” by Todd Webb, 1956, printed 2023, inkjet print, courtesy of Todd Webb Archive. ©Todd Webb Archive.

Frank, for his part, was a Swiss émigré of well-to-do Jewish parents, and with a restless, brilliant nature, and a personality “that ranged freely between the poles of optimism and pessimism,” Lisa Volpe, the MFAH’s curator of photography, writes. He, too, was interested in all things, Volpe said, but in particular in the ways in which the ambitions of the present foretold the future. He traveled more than 10,000 miles and took, by his estimate, more than 27,000 pictures.

Each man would be asked to reconsider their visions of America. “The reality — a hierarchical society obsessed with power and consumption and blinded by the empty ideologies of freedom and mobility — disheartened them. Yet, faced with this truth, Webb and Frank found their own means of expression,” Volpe adds.

For inspiration, the two took roads less traveled, and were drawn to a succession of untold stories. Webb captured a massive graveyard for automobiles in one image; Frank was drawn to a Memphis shoeshine (man?) laboring in a grimy men’s room in obscurity. Webb caught an image of an elderly merchant, bookended by “Going out of business” signs outside his shop. Frank zeroed in on a street scene in LA but made the crowd of everyday people his subject as opposed to the aspiring starlet whose visage is noticeably out of focus. There is a young man in Nevada in front of a jukebox, selecting a tune; and a truly hilarious pull-out-the-stops scene of galloping horsemen brandishing American flags at a rodeo. God Bless America, for sure.

“Rodeo, New York City” by Robert Frank, 1955-56, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Museum purchase funded by Jerry E. and Nanette Finger. ©The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation.

When the US edition of Frank’s book, The Americans, came out in 1958, it caused an uproar. The New Yorker’s cultural critic Janet Malcolm, called Frank “the Manet of the new photography,” and asserted that The Americans would transform Twentieth Century photography.

“Before The Americans, journalistic photography was more about the captions than the photographs,” the film producer Laura Israel, whose retrospective on her longtime friend and colleague was completed just two years before his death, observed. “You couldn’t have a photograph that said something striking in the image. His photographs didn’t need captions but also rather than trying to explain something, they evoked a feeling.” Israel likened Frank’s style of creation to the bursts of energy espoused by the Beat Poets, several of whom were his friends and neighbors in Greenwich Village.

“Patriotism, optimism and scrubbed suburban living were the rule of the day,” the journalist Charlie Le Duff observed in an article published in Vanity Fair in 2008. “Myth was important then. And along comes Robert Frank…the European Jew with his 35mm Leica, taking snaps of old angry white men, young angry black men, severe disapproving southern ladies, Indians in saloons, he/shes in New York alleyways, alienation on the assembly line, segregation, south of the Mason-Dixon line, bitterness, dissipation, discontent.” The era of street photography had arrived.

“New York City” by Robert Frank, circa 1947-51, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation. ©The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation.

Ironically, Webb’s work would be absent from the conversation for some 60 years, as the result of a disastrous business deal. Some 10,000 prints made during his journey were tucked away in padlocked steamer trunks and were only rediscovered in 2016. The Portland, Maine-based Todd Webb Archive has been instrumental in introducing Webb’s work to new generations. Three other shows, with published catalogs, have included “After Atget: Todd Webb Photographs: New York and Paris” (Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2011); “I See a City” (Museum of the City of New York, 2017) and “Outside the Frame: Todd Webb in Africa” (Minneapolis Institute of Art, Portland Museum of Art, Maine, 2021), which have preceded “Robert Frank and Todd Webb: Across America, 1955.” America and its Myths, the fascinating catalog written and produced by Volpe, takes us back to post World War II life, and deconstructs the myths that were often being ingested at TV tables in the country’s living rooms.

Both men were disheartened by the racism they encountered on the road — but each retained hope in the country’s potential to grow and change. By documenting what he saw as the country’s inequalities, whether the Black domestic servant in Charleston, S.C., caring for an infant from an affluent family. Or the work, “Trolley-New Orleans,” in which passengers appear segregated within a caste system and made visible by the ready-made partitions of the vehicle’s window frames, Frank said, “There is a lot here that I do not like and I would never accept.” “I am also trying to show this in my photos.”

“Robert Frank and Todd Webb: Across America, 1955” leaves us with many lingering images — and much to ponder. What is it about our cowboys and train depots and grain elevators, our diners and coffee shops, American flags and parades? And what about those gas pumps, popping through the dusty earth, with their seeming promise of prosperity and opportunity? America was on the move — but where was it heading?

“US 285, New Mexico” by Robert Frank, 1955, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Museum purchase funded by Jerry E. and Nanette Finger. ©The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation.

Robert Frank kicked documentary photography into the present “with a loud clang,” Arthur Lubow, a cultural critic writing for The New York Times, asserted upon the artist’s death. Frank had moved away from the detached formalism of Walker Evans and the poetic lyricism of Henri Cartier-Bresson, he said. Yet Webb’s softer-spoken visual commentary remains potent as well to this day. Juxtaposing Frank’s often- cinematic, grainy, off-kilter shots with Webb’s measured meditations seems quintessentially American, even in 2023.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is at 1001 Bissonnet Street. For information, 713-639-7300 or www.mfah.org.