“Long Branch, N.J.,” 1869, oil on canvas. The Hayden Collection — Charles Henry Hayden Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

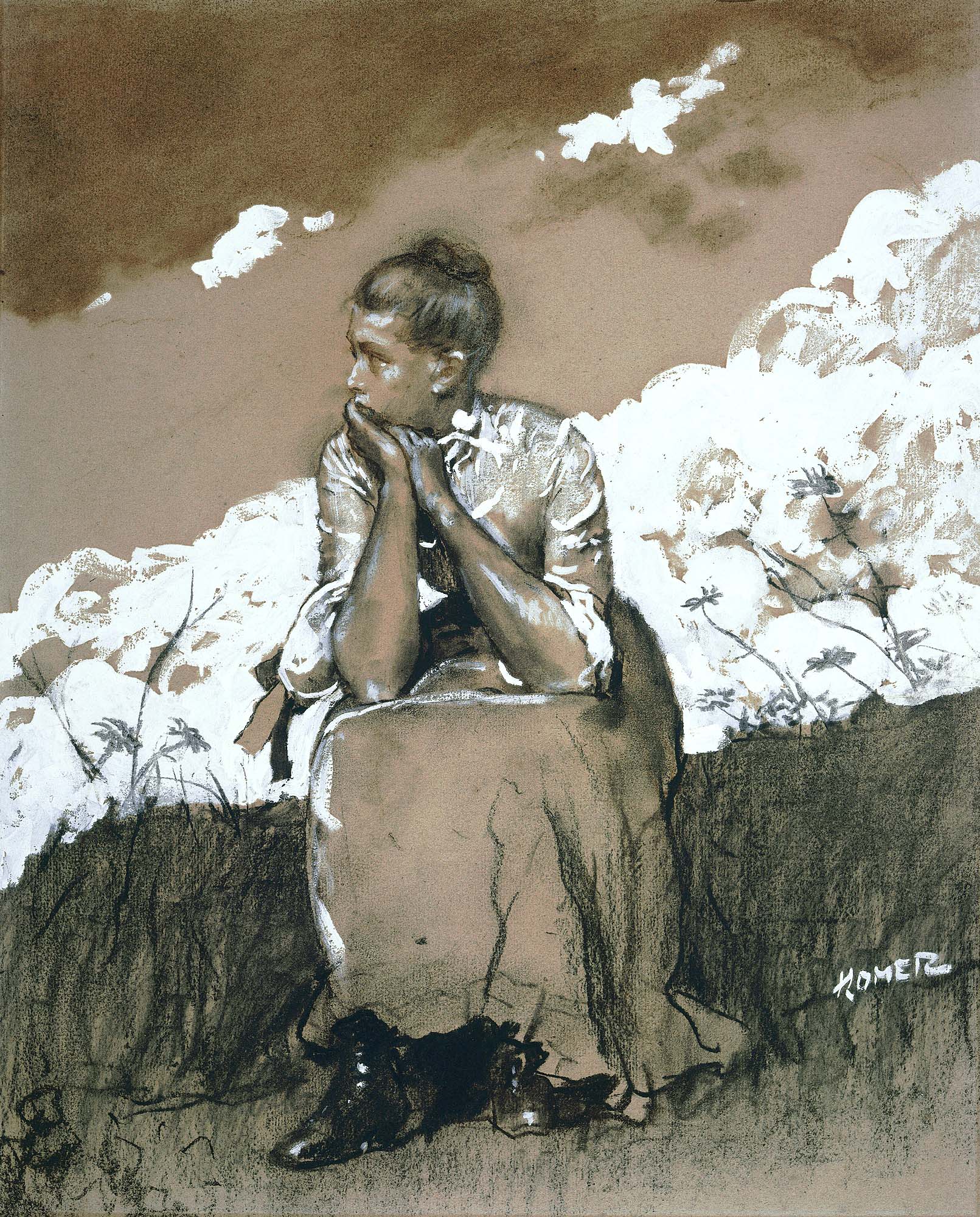

BOSTON — The title of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s new Winslow Homer exhibition comes from the novelist Henry James, also an occasional art critic, who wrote in 1875 that Homer “naturally sees everything at once with its envelope of light and air.” The quote is interesting, in part, because James was not always Homer’s biggest fan, both before and after offering this well-observed take on his watercolors. The art form in general had long suffered from critical skepticism, generally seen either as a minor step on the way to more fully realized oils or an outlet best suited to women and amateurs.

That has all changed now, of course, and Winslow Homer (1836-1910) is a big part of the reason. “Of Light and Air: Winslow Homer in Watercolor,” on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) until January 19, offers visitors the opportunity to lose themselves the straight-up virtuosity of the artist’s work in this medium. The exhibition brings the MFA’s nearly 50 Homer watercolors — the largest collection anywhere — together in one space for the first time in 50 years.

Boston, specifically the MFA, has always been a destination for Homeriana, tracing back to the artist’s own deep roots there and in nearby Cambridge. Bostonians enthusiastically collected the work of this hometown hero during his lifetime and after — often from local gallery Doll & Richards — and many later gave them to the MFA. Such was the case with “The Fog Warning,” arguably Homer’s most famous work in oil (and one of the museum’s most famous works, full stop), which was a centerpiece in the MFA’s sweeping Homer retrospective in 1995, titled simply “Winslow Homer.”

“The Fog Warning,” 1885, oil on canvas. Anonymous gift with credit to the Otis Norcross Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Of Light and Air” is similarly retrospective in scope, ranging from the artist’s earliest efforts (his mother, watercolorist Henrietta Benson Homer, introduced him to the art form) to his late surges of travel to places ranging from Canada to the Caribbean, invariably documented in watercolor. It also includes “The Fog Warning.” The difference here, say co-curators Christina Michelon and Ethan Lasser, is that the script is flipped. Whereas in 1995 — and in most other major Homer shows, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent “Crosscurrents” — the show was built around such major oils, with watercolors serving a secondary and supportive role, the opposite is true here. Here, the watercolors have “their breathing room and their space and their moment of celebration,” says Michelon. Even so, the curators have chosen a “mixed-media hang . . . so that these pieces could talk to one another.”

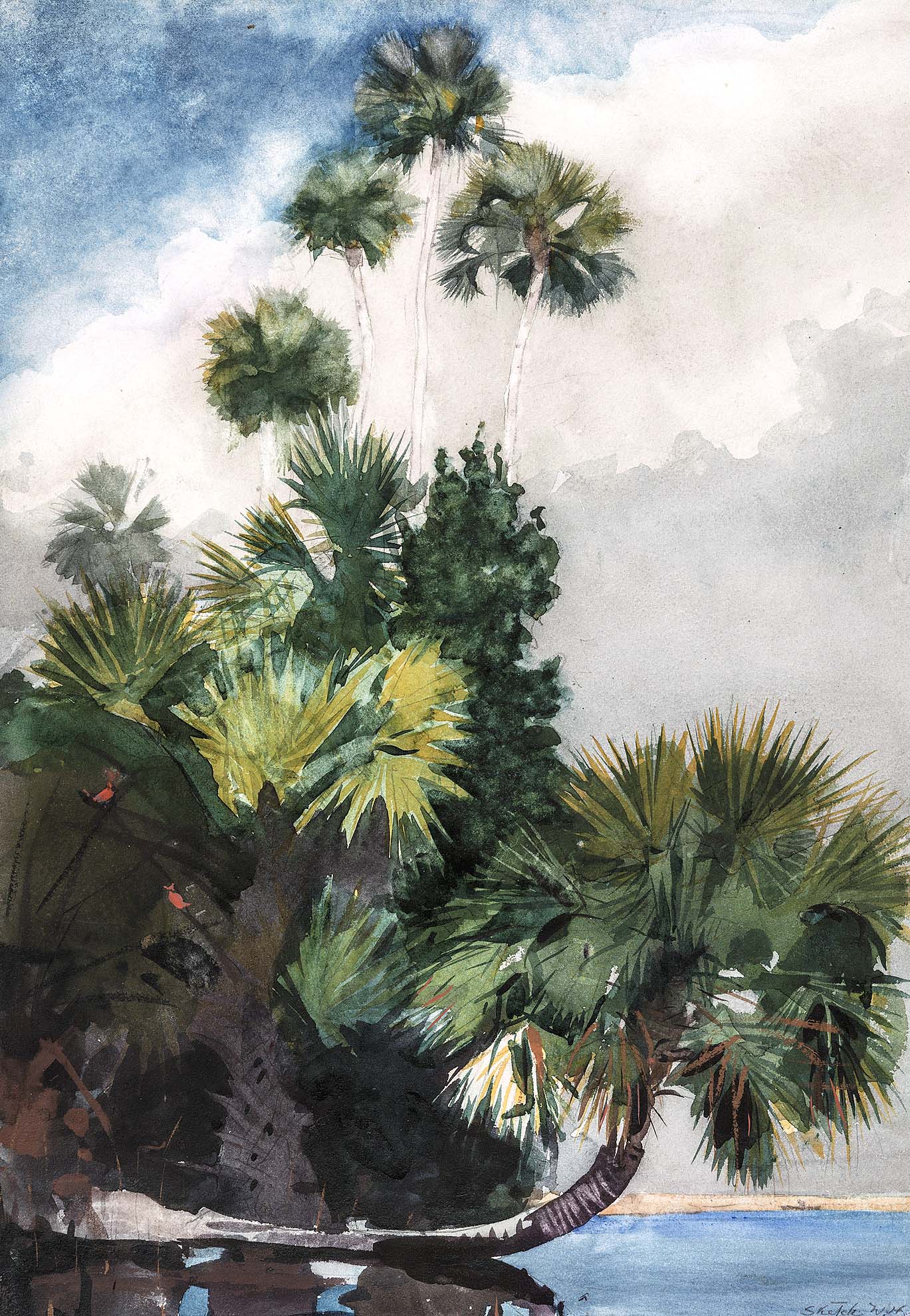

Another key difference from the earlier retrospective, a huge loan exhibition co-organized with the National Gallery, is the home-grown nature of the present show. “It’s drawn almost 99 percent from our own holdings,” says Lasser, adding, “we’re very proud that we can still represent almost every chapter” of Homer’s career. In that regard, there have been small but important assists from the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Maine, which lent some of Homer’s youthful works as well as some by Henrietta Homer, and the Portland Museum of Art (Maine), which shared one of its own closely guarded watercolors to expand the offerings from Homer’s time in Gloucester, Mass., in the 1870s. The Portland Museum of Art also lent Homer’s watercolor box, still bearing the traces of his color mixing on the lid, a relic without which no Homer watercolor show would be complete.

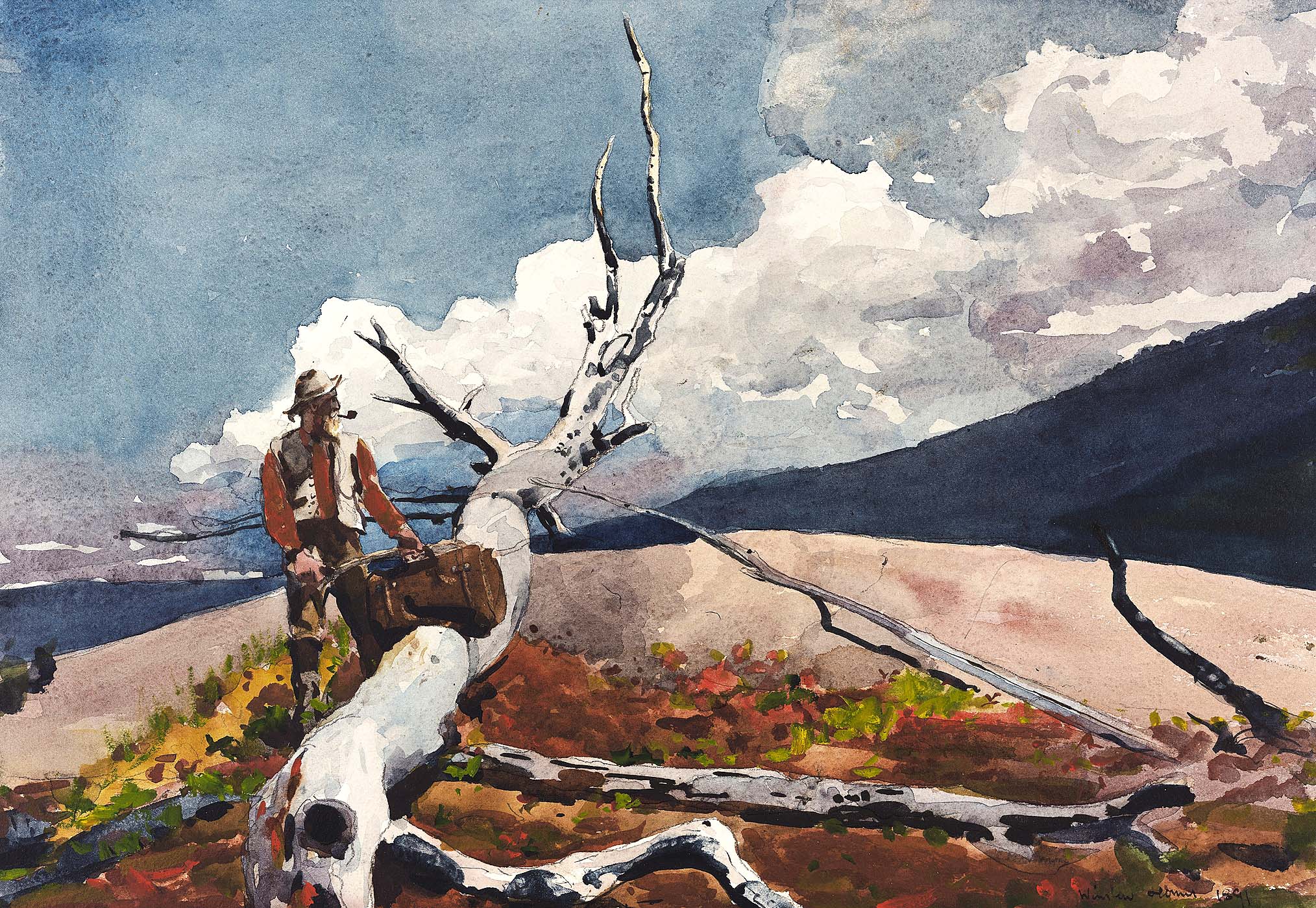

“The Adirondack Guide,” 1894, watercolor over graphite pencil on paper. Bequest of Mrs. Alma H. Wadleigh. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Michelon also points out a key loan from the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, N.H.: an 1894 watercolor of an Adirondack guide in a canoe (“In the North Woods”), which she has displayed alongside the MFA’s own chromolithograph of the painting made just one year later. This pairing calls up a phrase in the museum’s promotional materials for the show — that it encompasses the “ecological, artistic, social and economic” environments that shaped Homer’s work in watercolor. Of these environments, the “economic” one might seem the most difficult to parse, but this example shows what Michelon calls his “savvy” as a businessman, accepting an offer to mass-reproduce a painting almost as soon as it left his brush. “In a lot of his letters, he’s talking about the joy of painting watercolors and also his hope to sell them,” she notes. “I think the economic dimension of his career was never not on his mind.”

Lasser also points out that the inscription “This will do the business” on the back of the Adirondack watercolor “The Blue Boat” is open to interpretation, either expressing his pride in the work or predicting its salability. Maybe both. Michelon says it is a fan favorite among MFA visitors, and it’s fair enough to point out that it is a mainstay of its shop products.

It is clear that “Of Light and Air” does several things most other Homer shows have not. Because watercolors must be displayed under reduced lighting to prevent them from fading, they usually occupy a sequestered space within larger exhibitions so that the oils can receive the full benefit of dazzling illumination. But here, they manage to share the same walls (with the oils, again, playing a supporting role), a feat for which Lasser credits the MFA’s skilled exhibition design team as well as the controlled lighting of its subterranean galleries for special exhibitions.

“An Afterglow,” 1883, watercolor over graphite pencil on paper. Bequest of William P. Blake in memory of his mother, Mary M. J. Dehon Blake. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

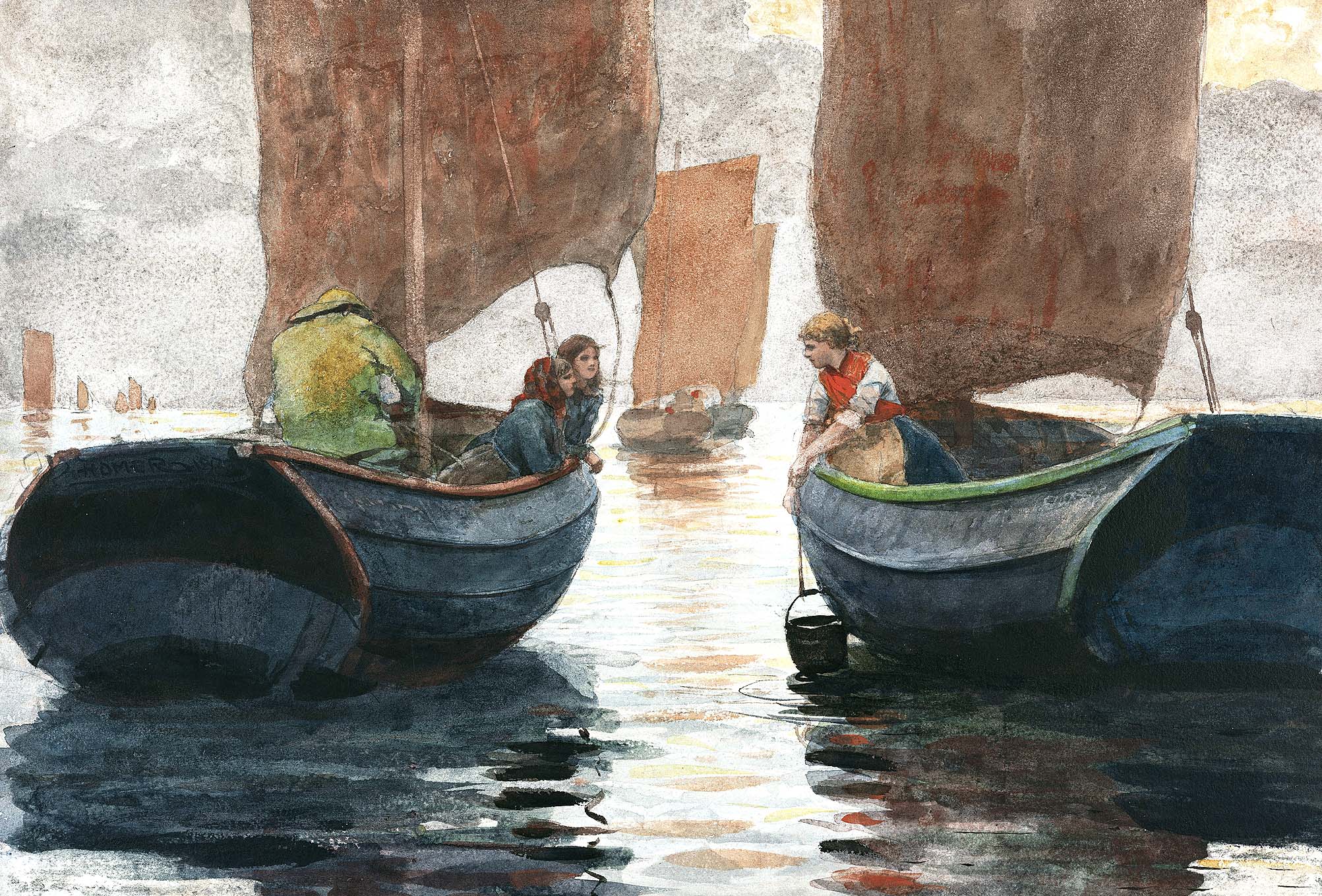

There is also a tendency, in books as well as exhibitions about Homer, to separate out the works from different places and phases of his career and to treat them in isolation: one chapter or section for the shipyard scenes in Gloucester; one for the noble fisherfolk of Cullercoats, England; one for the views from his studio in Prouts Neck, Maine; and yet another for his works from Bermuda and the Caribbean. Not so here, where the curators have attempted to think more holistically about, in this example, his engagement with the sea across place and time.

“They are, in many ways, very different moments, but we’re putting them together,” Lasser says, adding that he has never seen the works put together in this way before. Nevertheless, the integrated display has some precedent. Lasser notes that “The Fog Warning,” a scene from the North Atlantic fishing grounds that Homer painted at Prouts Neck, was first shown at Doll & Richards with a selection of Caribbean watercolors, a display that blended both place and medium. “Clearly Homer had some reason” for displaying these works together, Lasser says, “something he saw, something in common. Instead of always thinking about difference, we can think about similarity.”

The curators’ decision to organize the show in a more visual than chronological or didactic way emphasizes Michelon’s answer to the rote question, “Why Homer, why now?” Beyond introducing a new generation to these rarely seen paintings, she says, “it’s a show full of works that lend themselves to very rewarding, close and slow looking . . . an opportunity to slow down and just really appreciate these scenes.”

“The Dory,” 1887, watercolor over graphite pencil on paper. The Hayden Collection — Charles Henry Hayden Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Lasser adds that the “bright, luminous, vibrant” works are perhaps particularly needed and welcome during the darkest time of the year and what many are experiencing as a dark time in US history. “You can go through the show and learn a lot about Homer and learn a lot about watercolor,” he says, “but we also want to invite you just to go through the show and spend time immersing yourself in the works themselves, in their many layers of color and light and air and evocation, poetry.”

There is much in the MFA show to support that viewing experience, including an illustrated diagram of Homer’s techniques, courtesy of longtime MFA conservator Annette Manick and her team. A film with Homer conservator Judy Walsh and contemporary watercolorist James Prosek also offers analysis and demonstrations of how Homer achieved certain effects. Lasser paraphrases Walsh as saying that anyone who picks up a watercolor brush “has to reckon with Homer,” and Prosek that Homer is the “greatest watercolorist, period.” The way that Homer has maintained his relevance among contemporary artists is a cornerstone of his legacy. “It’s one thing to live in a world of historians,” Lasser says, referring to artists’ legacies in general. “Everyone kind of lives in the world of historians. But if you live in a world of artists, that says something about your work,”

The MFA has also produced a catalog for the exhibition, co-written by Michelon and Manick, that blends art historical and technical analysis. Frequent interpolations drill down into Homer’s materials and techniques with accessibly written notes on everything from graphite and opaque pigments to wet-on-wet and drybrush techniques. Positioned strategically alongside reproductions of works that illustrate key points, these technical forays encourage the kind of nose-to-the-paper close looking that is frowned upon in the actual galleries of the MFA. But no matter how detailed and beautiful the book’s reproductions — and they are beautiful, with all-new photography — they are no replacement for the real thing.

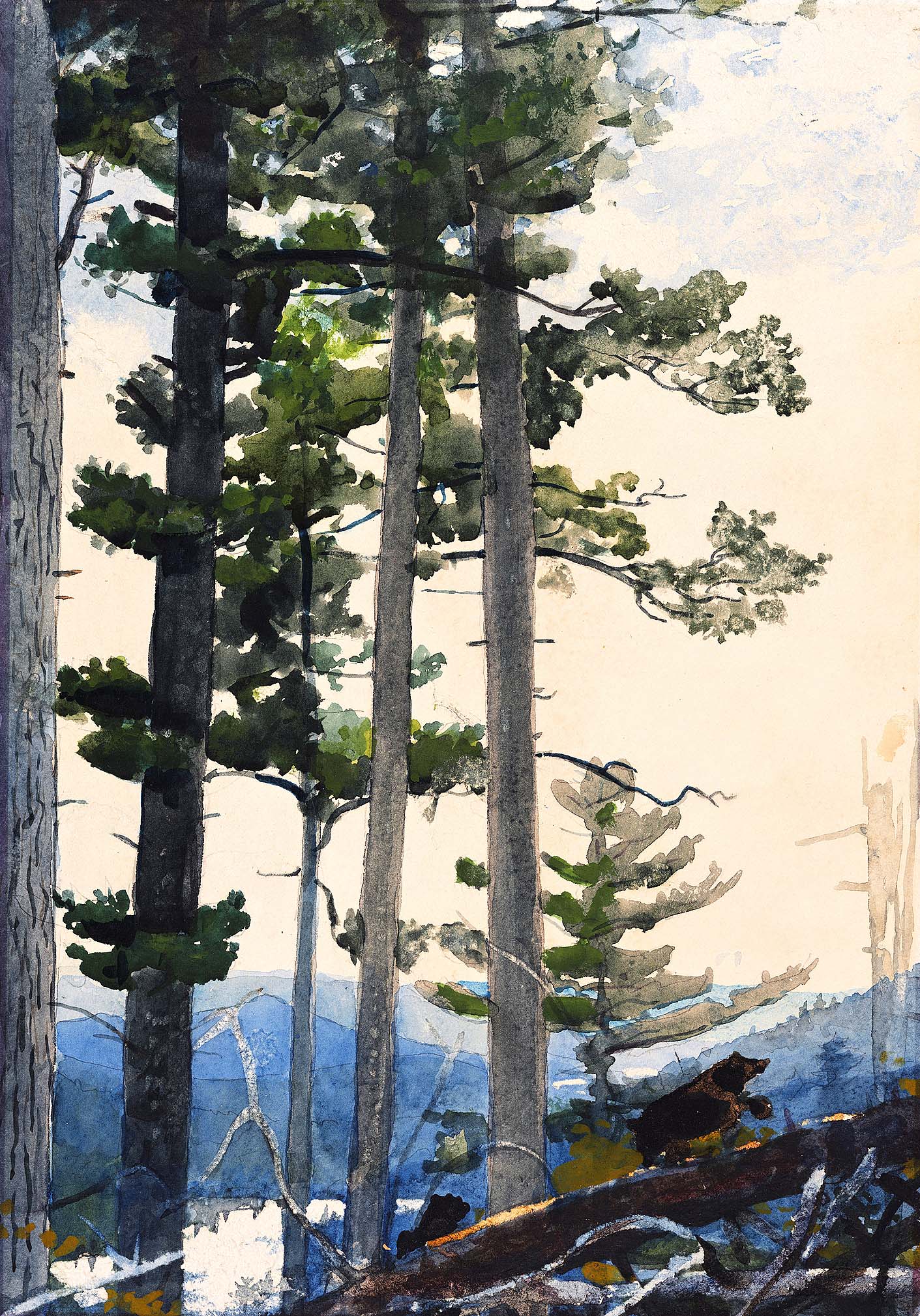

“The Guide and Woodsman (Adirondacks),” 1889, watercolor over graphite pencil on paper. Bequest of John T. Spaulding. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

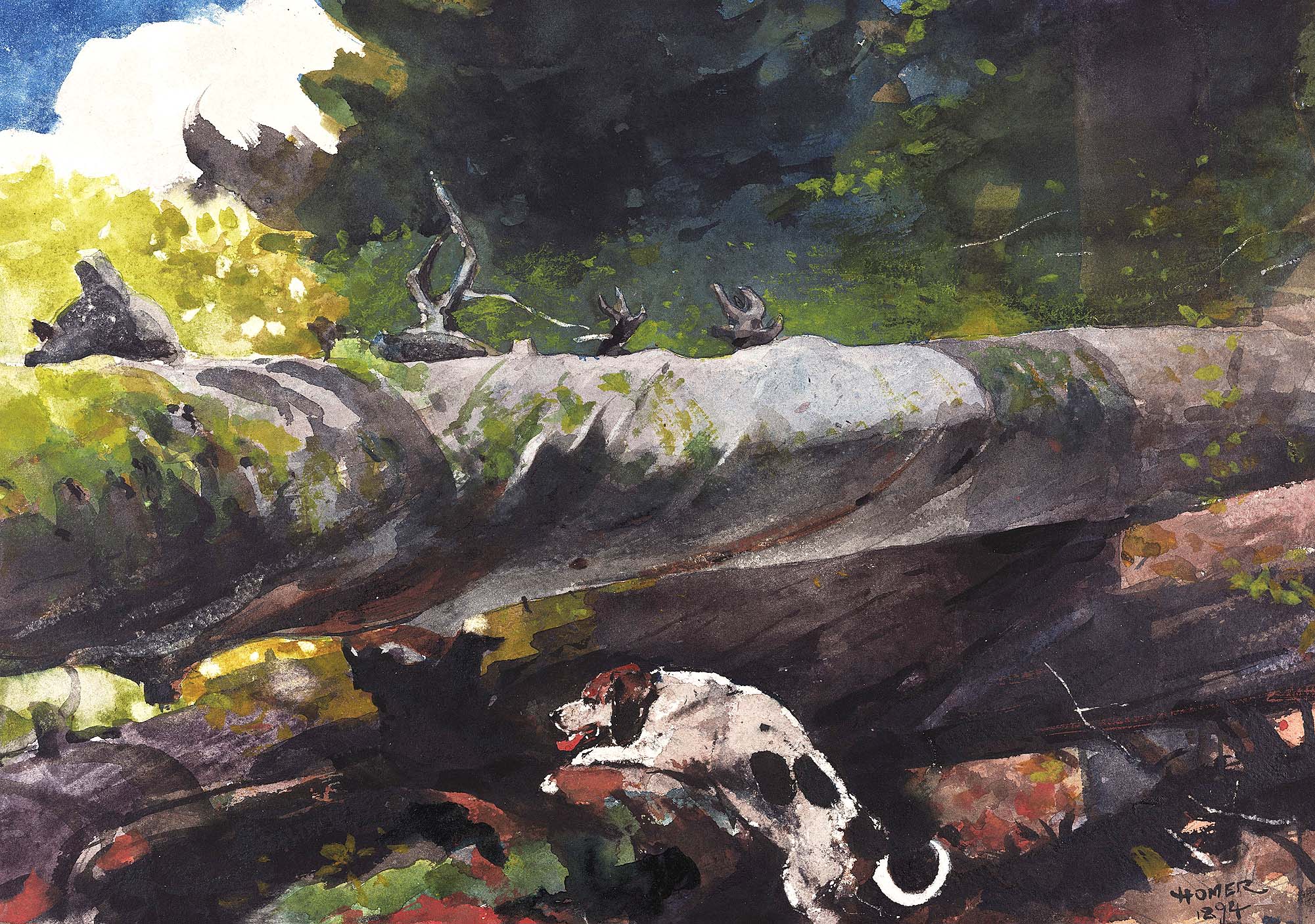

In the interest of full disclosure, it was my misfortune, as it often is for arts writers, to have to consult the artworks on my computer screen in order to file my story on time; they had not yet gone up on the walls in Boston. Although I have been lucky enough to see and work with Homer watercolors in the past, and therefore might try to describe for readers the small wonders that they present — the rich, complex greens and browns of the undergrowth in “Driving Cows to Pasture” and “The Guide and Woodsman”; the mesmerizing broken reflections in “The Blue Boat”; the animated sense of flight in “Rocky Coast and Gulls” and “Leaping Trout”; the uncanny stain of smoke in “Fisherman’s Family (The Lookout)” — that would be at best a description of a description of an experience. Better to see for yourself how Homer saw things: “all at once” and in an “envelope of light and air.”

Homer is rumored to have once said to a friend, “You will see, in the future I will live by my watercolors.” Like the “this will do the business” quote, his words could predict either monetary success or an enduring legacy. It is fortunate for us, just as it was for him, that he never had to choose between one or the other.

The Museum of Fine Arts is at 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston. For information: www.mfa.org or 617-267-9300.