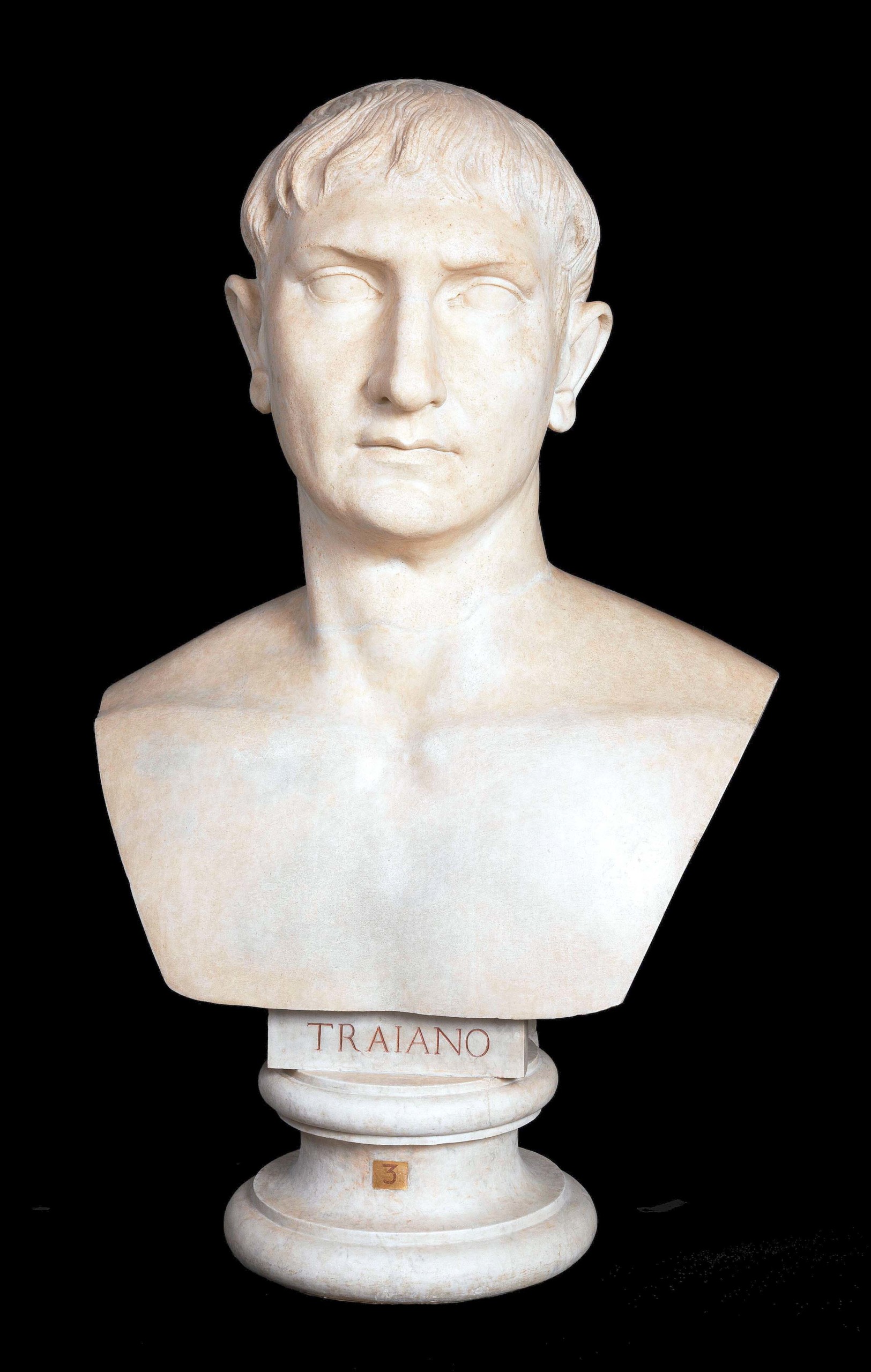

Statue of Trajan, Minturno, Italy, Second Century, marble. National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

By James D. Balestrieri

HOUSTON — Not long ago, a meme ran rampant through social media (big surprise): men think about the Roman Empire all the time. Why? For very male reasons, as it turns out, most of which have little or nothing to do with actual history. Gladiators, for one. Legions on the march, doing battle with barbarians of vague and various sorts. Gods, orgies, sex — all of these partaking far more of myth than of reality. But this idea of men thinking about Ancient Rome was enough of a sensation to make to mainstream news, where I saw it. At about the same time, another meme began to go around, one that goes something like this: when men imagine themselves in history, they are always badass heroes; when they imagine themselves in a sci-fi future, they are intrepid explorers of galaxies far, far away. In life, on the other hand, they’re unhappy middle managers who are terrified of their bosses. If this is true — and, like all memes, it must be taken with a grain of salt — it’s no wonder that the muscular image of Roman Empire makes it into the Walter Mitty daydream.

Of course, there was a real Roman Empire, an empire that grew out of the dissolution of a long-lived Republic. The true story of the Roman Empire is long, complex and fascinating — without the embellishments of popular culture. Excavations and scholarship continue to add to her history. There were between 82 and 92 emperors, including one empress in all but name, depending on how you define an emperor, from Augustus beginning in 31 BCE and ending with the reign of Romulus Augustulus in 476 CE. By the time of the last emperor, power had shifted from the Italian peninsula and Rome to the provinces. The capital of the empire itself had moved east, to Asia Minor, to what had once been the outpost of Constantinople. And Christianity, born in a desert outpost, had grown from an enemy of Rome to become the official state religion. In what is perhaps the most striking example of historical irony, we might argue that the provinces — the kingdoms cultures Rome had assimilated into the empire — conquered Rome long before Rome fell.

Sepulchral relief with Circus, Rome, Italy, Second Century, marble. Gregorian Profane Museum, Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

In a partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), and the Saint Louis Museum of Art, “Art and Life in Imperial Rome: Trajan and His Times” at the MFAH and “Ancient Splendor: Roman Art in the Time of Trajan” at the Saint Louis Museum brings nearly 160 objects from the time of Trajan to viewers; many of these have never before been seen in the United States. Lenders to the exhibition include the Museo Nazionale Romano, the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, the Parco Archeologico di Ostia and the Musei Vaticani.

Emperor Trajan’s reign came relatively early in the pantheon of Roman leaders, at a time when the empire was at the height of its power. Yet Trajan’s life, times and interests show that the empire’s longevity and ultimate destiny resided far from the heartbeat of the city of Rome. Trajan was born in either 53 or 56 CE. His family was originally from Umbria but had migrated to the city of Italica in Romanized Baetica, now Andalusia, Spain. His ascension to the throne thus makes him the first — of many — emperors who were not born in Italy. The son of the governor of the provinces of Syria and Africa, Trajan rose to prominence in the military and was seen as a popular candidate when the childless Emperor Nerva adopted him formally in 97 CE. Adoption signaled succession and, as all emperors did, Trajan returned the favor once he ascended, deifying Nerva. Trajan himself suffered a stroke and passed away while on the march in the city of Selinus in Cilicia, far from Rome, in 116 CE.

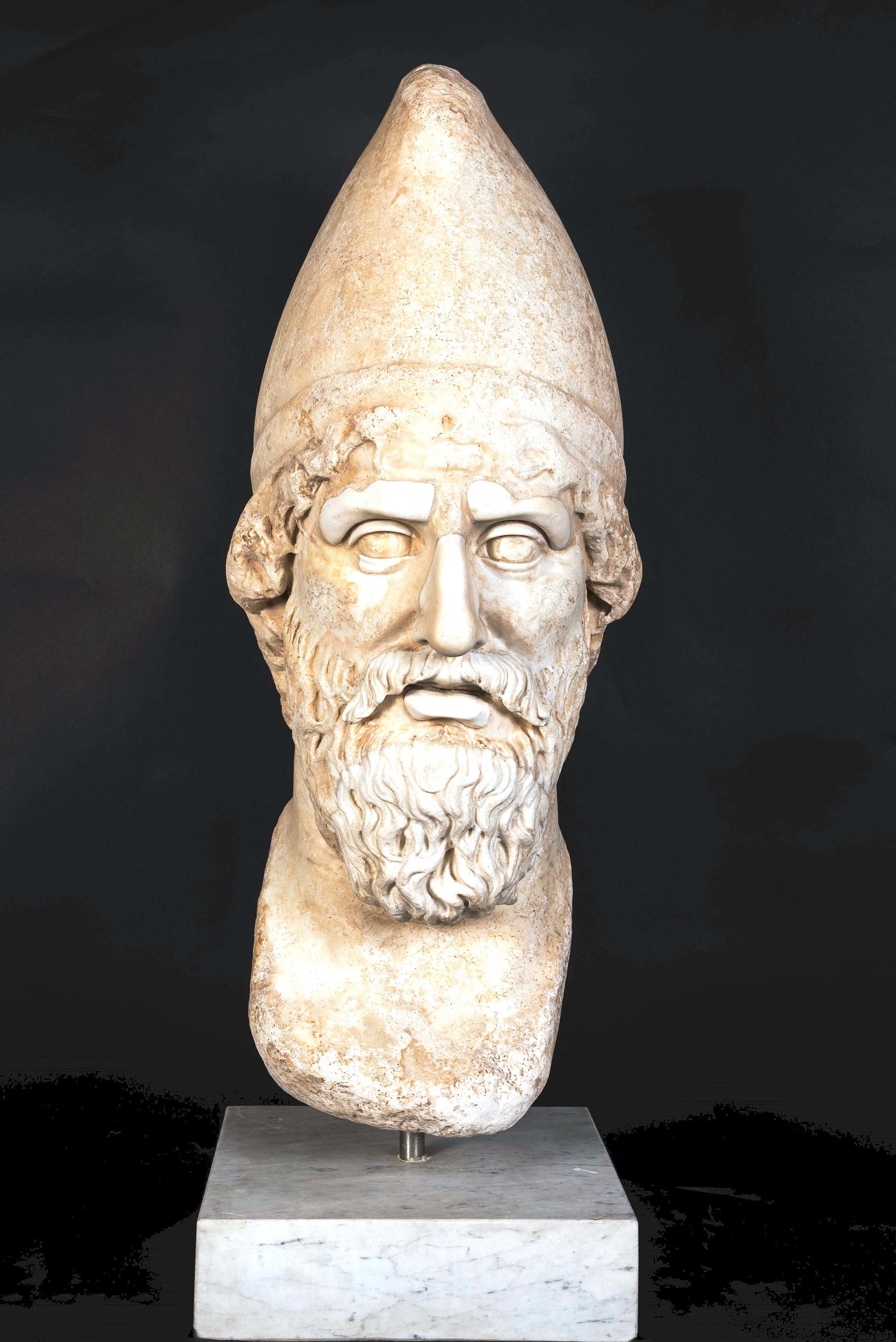

Colossal portrait of Trajan, Rome, Italy, Second Century, marble. Chiaramonti Museum, Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

Trajan’s heart’s desire was to surpass the conquests of Julius Caesar, and he set his sights on the creation of new provinces in Arabia, Mesopotamia and Armenia. His plans met with resistance, and he was compelled to deal with fierce Parthian and Jewish rebellions. Trajan may not have achieved his highest ambition, but what is certain is that the Roman Empire reached its greatest extent during his reign from 98-117 CE. His conquest of Dacia, a kingdom bounded by the Danube River to the south and the Black Sea to the east — comprising most of contemporary Romania — and his transformation of the kingdom into a new province (once he had transferred a great deal of its wealth, including gold, to the imperial treasuries) after the campaign of 105-106 CE, would become Rome’s last major imperial acquisition.

As an administrator, Trajan safeguarded the grain supply, extended free distribution of food to the poor and made special provisions for poor children. Rather than oppressing them, he sought to bring Christians back into the fold of Roman religion, though the practice of Christianity was still forbidden and subject to punishment. In the realm of public projects, Trajan oversaw the construction of extensive baths, a new Forum and the magnificent Column of Trajan, which, as the exhibition text states, is “a towering pillar with a spiraling narrative frieze that is one of the few monumental sculptures to have survived the fall of Rome. Its 155 scenes and 2,662 carved figures depict two major campaigns against the Dacian kingdom.” A section of Trajan’s Column will be recreated especially for the exhibition.

The historian Dio Cassius, circa 165-circa 235 CE, lauded Trajan’s popularity and genuine concern for his subjects, as well as his common touch. At the same time, he also hinted obliquely at darker recesses in the emperor’s life: “He would enter the houses of citizens, sometimes even without a guard, and enjoy himself there. Education, in the strictest sense, he lacked, when it came to speaking, but its substance he both knew and applied. I know, of course, that he was devoted to boys and to wine. And if he had ever committed any base or wicked action as a result of these practices, he would have incurred censure…”

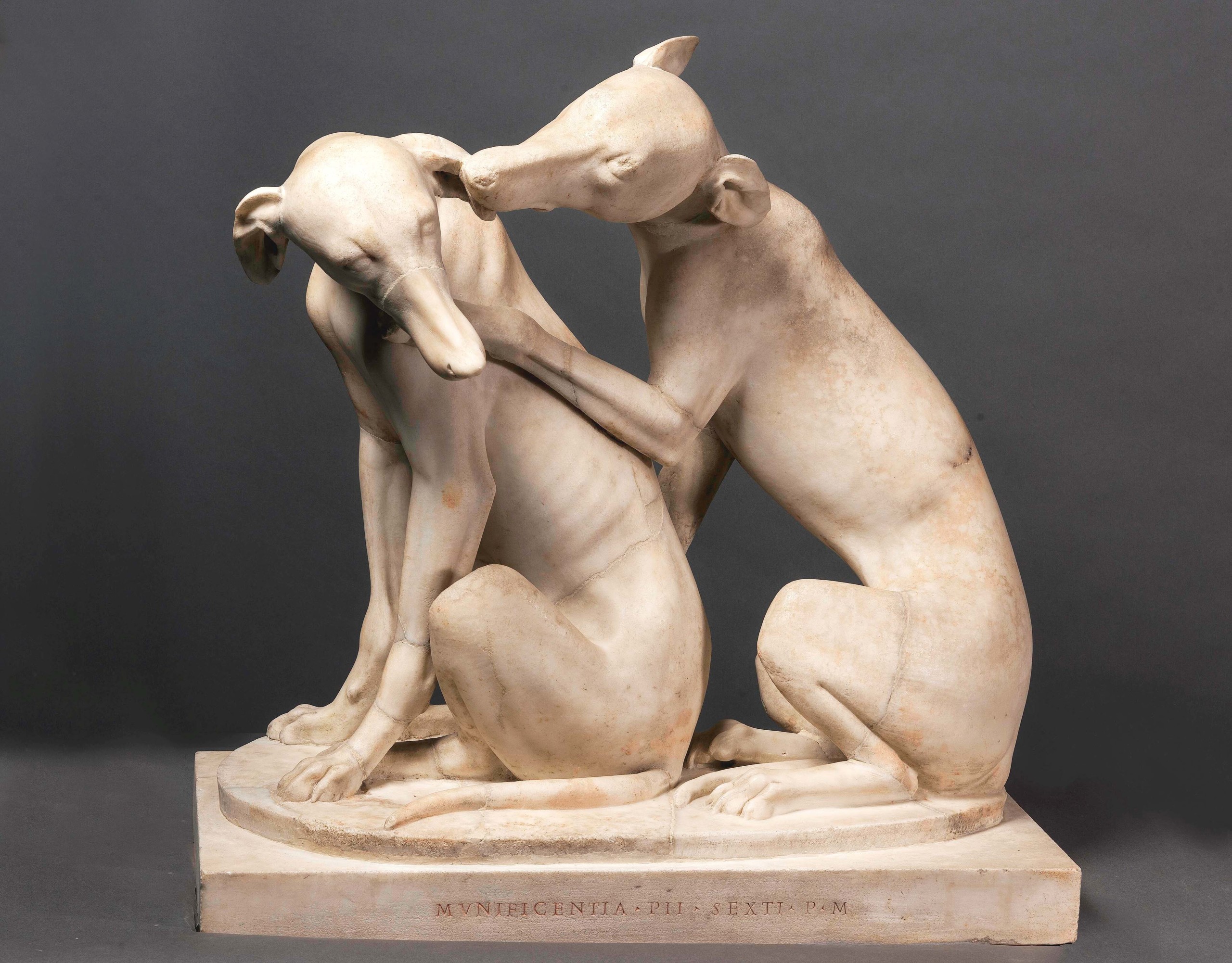

Group with two greyhounds, Villa of Antoninus Pius, Monte Cagnolo, Italy, Second Century, marble. Pio Clementino Museum, Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

Trajan was the second of what historians have called the “Five Good Emperors” of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. He presided over a period of growth, wealth and relative peace, at least at the center of the empire. The arts flourished as well, and images and ideas from the far-flung corners of the empire made their way to the capital — and to other provinces. Both the Statue of Trajan and the Colossal Portrait of Trajan, executed during or near his lifetime, suggest a fairly ordinary man, open and approachable, someone people could relate to, working hard to seem and ultimately become an emperor. Similarly, the Colossal Portrait of Plotina, Trajan’s wife, who came originally from Gaul, seems well matched with the images of her husband. There is something plain and appealing about them, despite the tone of austerity in their faces.

A sense of abundance, of prosperity and confidence permeates the works in the exhibition. A relief with harbor scene and personification of the Port, Ostia, and the statue of Sabina as Ceres, the Baths of Neptune, also from Ostia, exhibit the kind of detail we associate with great care and skill. In the relief, though a storm may toss the ship and its contents, the fire on the watchtower burns bright and the god of the port watches, unconcerned, petting an adoring bull. No intervention will be necessary.

In the carved group with two greyhounds, from the Villa of Antoninus Pius — who would become emperor after Trajan’s successor, Hadrian, an inveterate traveler who saw strength in the diversity of the empire, passed away — the dogs are rendered with scrupulous form and a contained, relaxed energy. Abundance could even be found under the feet of the Romans, as a mosaic pavement with fish attests. Yet no two fish are alike in the panel, redoubling the notion of plenty, a plenty that was there for the taking.

Mosaic pavement with fish, House of the Severi, Rome, Italy, Second Century, mosaic. National Roman Museum, Rome.

Like everything else, fashion moved from the provinces to Rome and back. When we consider the colossal head of a barbarian with tall pileus, a marble bust carved between 117-38, we don’t see an enemy, an alien, an other. There is no xenophobic exaggeration in the man’s features. His tall pileus only seems to excite curiosity and we can imagine a row of such busts in an early incarnation of a costume institute, each of them adorned with a headpiece from a different corner of the empire.

Games and circuses abounded in Trajan’s time. The sepulchral relief with circus offers a snapshot of spectators at a chariot race while Murmillo’s helmet with muses, figural scene with a young boy with musical instruments and theatrical masks, unearthed at Pompeii, unites gladiatorial practice with the performing arts. A truly spectacular object, this helmet appears to suggest insight into the perception of the ritual violence of gladiatorial combat as an art form. In the end, like all the objects in “Art and Life in Imperial Rome: Trajan and His Times,” the helmet might just carve a new, richer and wilder path, one that conquers the male daydreamers who routinely play parts in the Roman Empire meme.

“Art and Life in Imperial Rome: Trajan and His Times” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, at 1001 Bissonnet Street, through January 25. For information, 713-639-7300 or www.mfah.org.