“Portrait de Berthe Weill (Portrait of Berthe Weill)” by Émilie Charmy, 1910–14, oil on canvas, 35-3/8 by 24 inches. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Purchase, Annie White Townsend Bequest, 113.2024 ©Alberto Ricci. Photo: MMFA, Julie Ciot.

By Laura Preston

NEW YORK CITY — Twenty-two years ago, the late curator Julie Saul was reading a copy of Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth Century Art (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1995), Michael C. Fitzgerald’s study of Picasso and the dealers, collectors and critics who supported his career. The dealers in Fitzgerald’s book were familiar to Saul, as they would be to any historian of the Twentieth Century Parisian avant-garde: Ambroise Vollard, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Paul Rosenberg, among others. But another name caught Saul’s eye. Fitzgerald mentioned a dealer named Berthe Weill, whose tiny shop in Montmartre was crammed with antiques, prints and modern art. Despite Weill’s obscurity, her influence was enormous. She was the first dealer to sell Picasso, an early champion of the Fauves and the first and only dealer to exhibit Amadeo Modigliani in his lifetime. How was it that such a key figure of modernity was now forgotten? Saul’s search for answers led her to the MoMA PS1 library, which held a copy of Weill’s self-published memoir Pan! Dans l’oeil (POW! Right in the Eye!). Weill’s words leapt off the page. Here was a woman of high ideals and unwavering resolve, full of intensity, humor and grit. “I started out with just 50 francs in hand and went into debt to pay the costs involved in opening a shop…” she wrote. “What was the worst that could happen? Not being able to hang on? I will hang on!!!”

Saul’s decades-long obsession with Weill culminates this month at New York University’s Grey Art Museum, which presents “Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde.” The exhibition is co-curated by Lynn Gumpert, director of the Grey Art Museum; along with Anne Grace, curator of Modern Art of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Sophie Eloy, collections administrator at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris; and Marianne Le Morvan, a scholar of Berthe Weill. Saul passed away in 2022, before the exhibition was realized. The exhibition will travel to Montreal in May 2025, and complete its tour at the Musée de l’Orangerie in October of 2025.

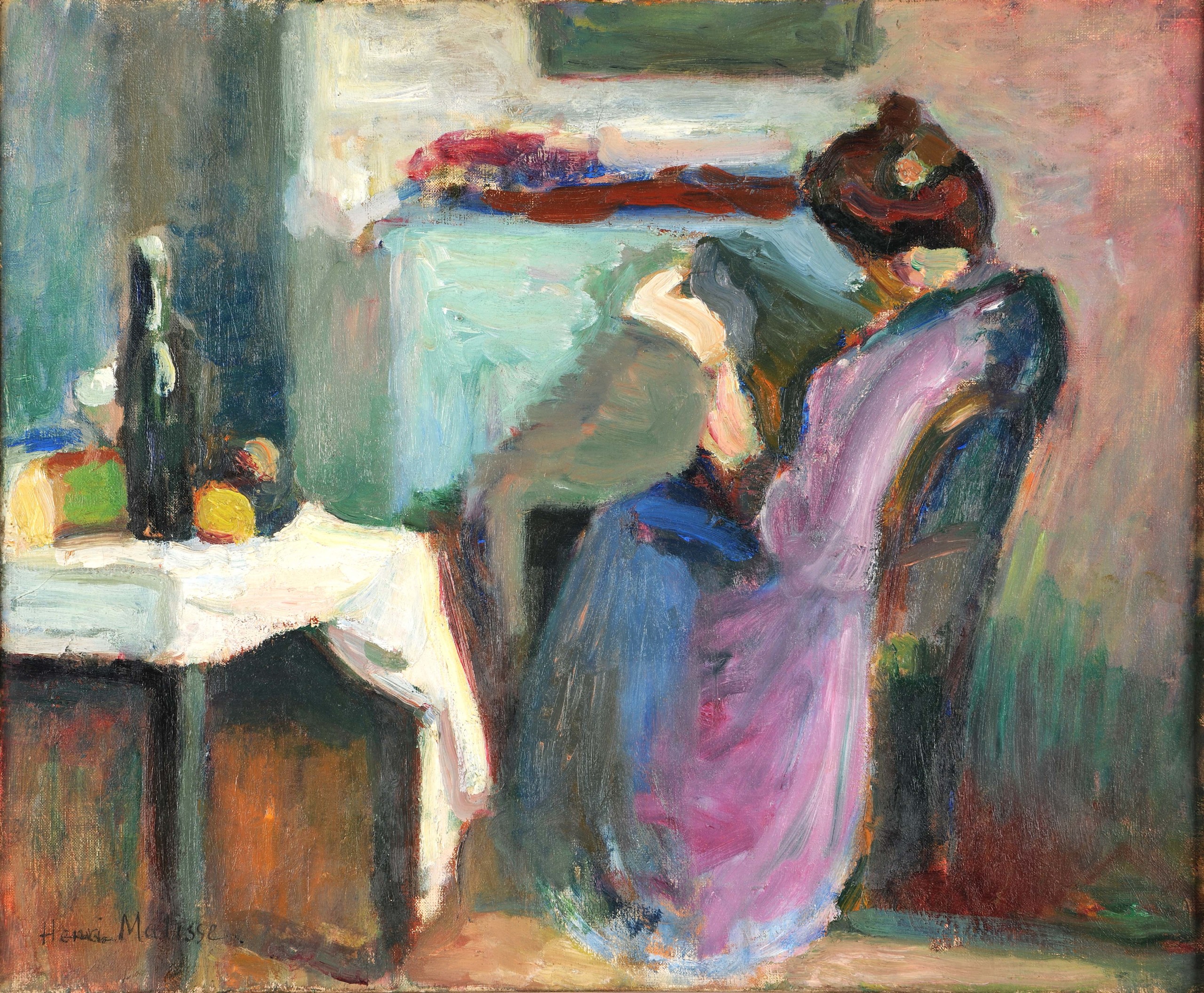

“Liseuse en robe violette (Reading woman in a violet dress)” by Henri Matisse, 1898, oil on canvas, 14-7/8 by 18-1/8 inches. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Reims, France. 949.1.40 ©2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Photo: Christian Devleeschauwer.

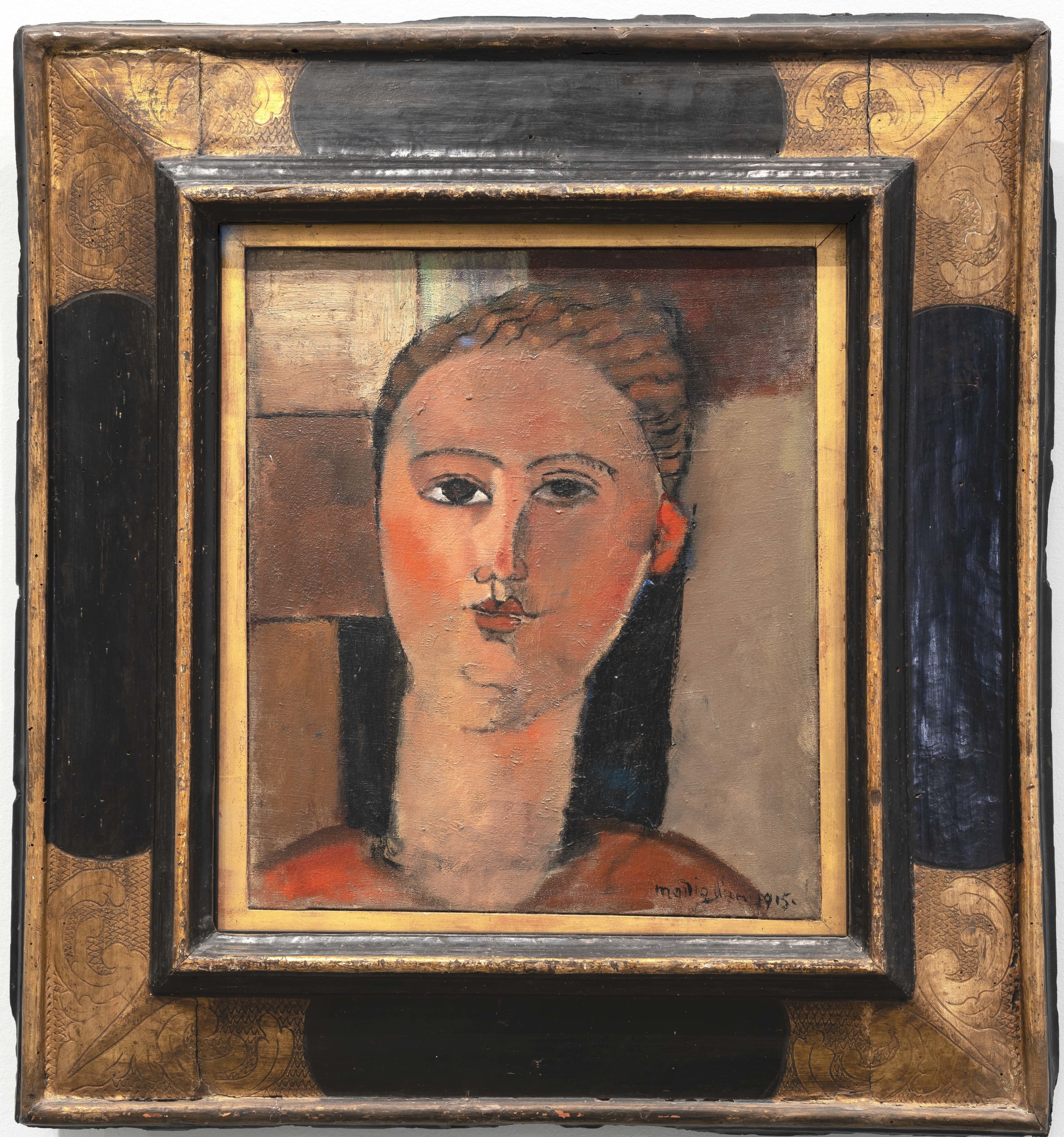

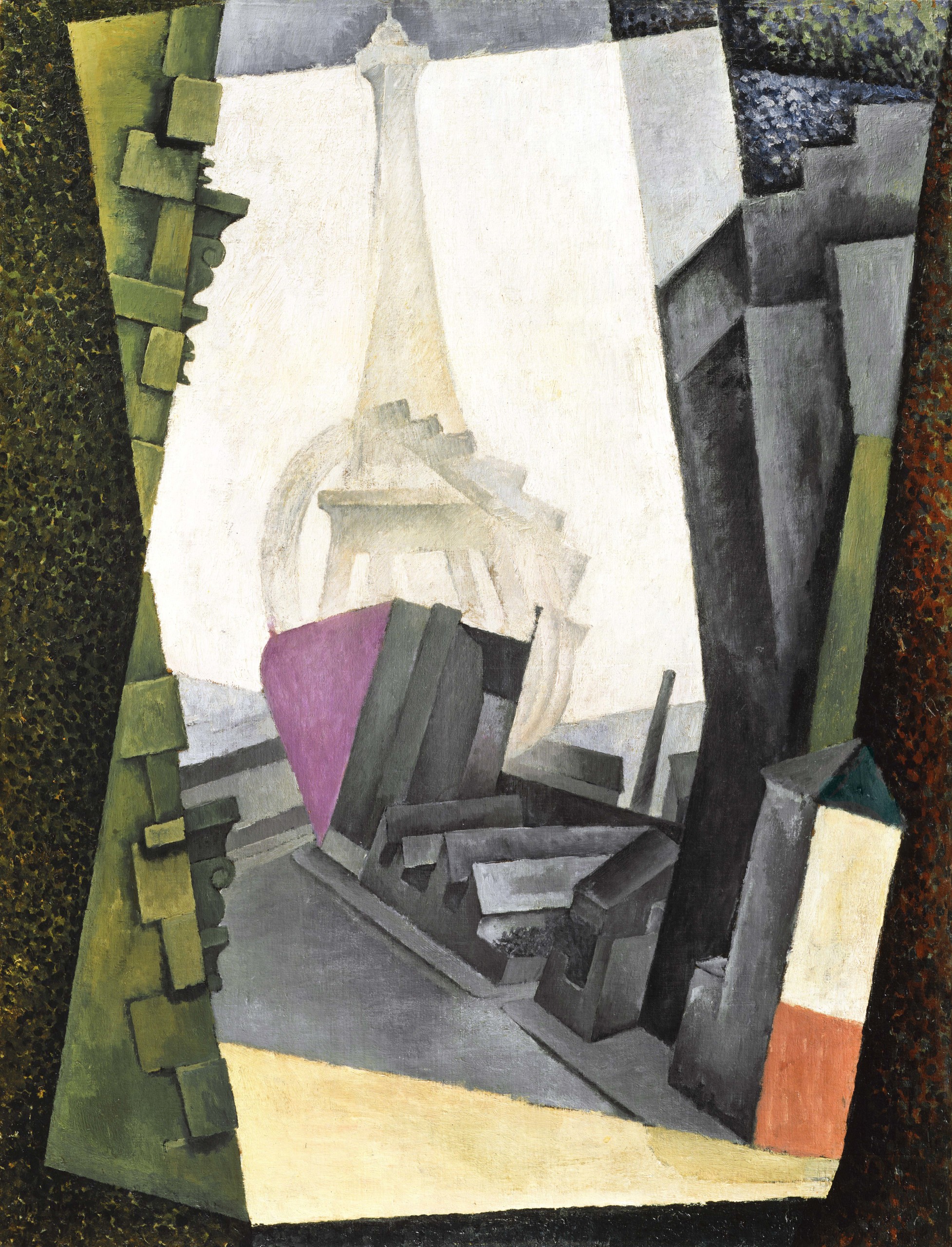

The Grey’s iteration will present some 110 works by artists in Weill’s circle. At first, the curatorial team was determined to only include works that had hung in Weill’s gallery, said Gumpert. But incomplete record-keeping and inconsistent titles made it difficult to verify certain works’ movements through the art market and complex international loan agreements made other works hard to secure. The team, instead, decided to show a mix of works. Some certainly hung in Weill’s gallery: an early Cubist rendition of the Eiffel Tower by Diego Rivera, for example, was made for the artist’s 1914 exhibition with Weill, his first solo show in Paris. Other works did not pass through the shop on Rue Victor Massé, but are nevertheless indicative of Weill’s cultural milieu, the breadth of her tastes and her personal relationships. Among the represented artists are many familiar names: Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Francis Picabia and Amedeo Modigliani. Perhaps more exciting are the less familiar ones: Émilie Charmy, Louis Cattiaux, Jules Pascin and Hermine David, among others. Each artist represents a node in the fascinating web of social and professional connections that defined the Parisian avant-garde and had Weill at its center.

A wonderfully loose, buttery painting by Émilie Charmy depicts Weill at the peak of her career. She stands proudly, dressed in black from the neck down, with her hair pulled back, a pair of round spectacles balanced on her nose and her head cocked in an inquisitive expression. Weill was an outsider by many counts. She was Jewish in a climate of antisemitism and a woman in a man’s industry. She deliberately abbreviated her gallery name to “B. Weill Galerie” to obscure her gender. Her class background also set her apart. She was the daughter of a seamstress and a ragpicker, and left school in her early teens to enter the workforce. Finally, she was the only gallerist in Paris who committed herself entirely to the promotion of young and emerging artists. While other galleries presented new talent alongside old standbys, like the Impressionists, Weill was voracious for the new. Her business cards read “Place aux Jeunes,” or “make way for the young,” and she strung her cramped shop with clotheslines from which she hung canvases that had not yet dried. She was so committed to helping artists in the early stages of their careers that she refused to lock them into exclusive contracts. Inevitably, her most successful artists would leave for more prominent galleries, but Weill never minded. Her deepest conviction was that artists needed resources and freedom to experiment. Weill’s staunch principles meant that she was always teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, but she always somehow managed to scrape by. “She was incredibly ballsy,” said Gumpert.

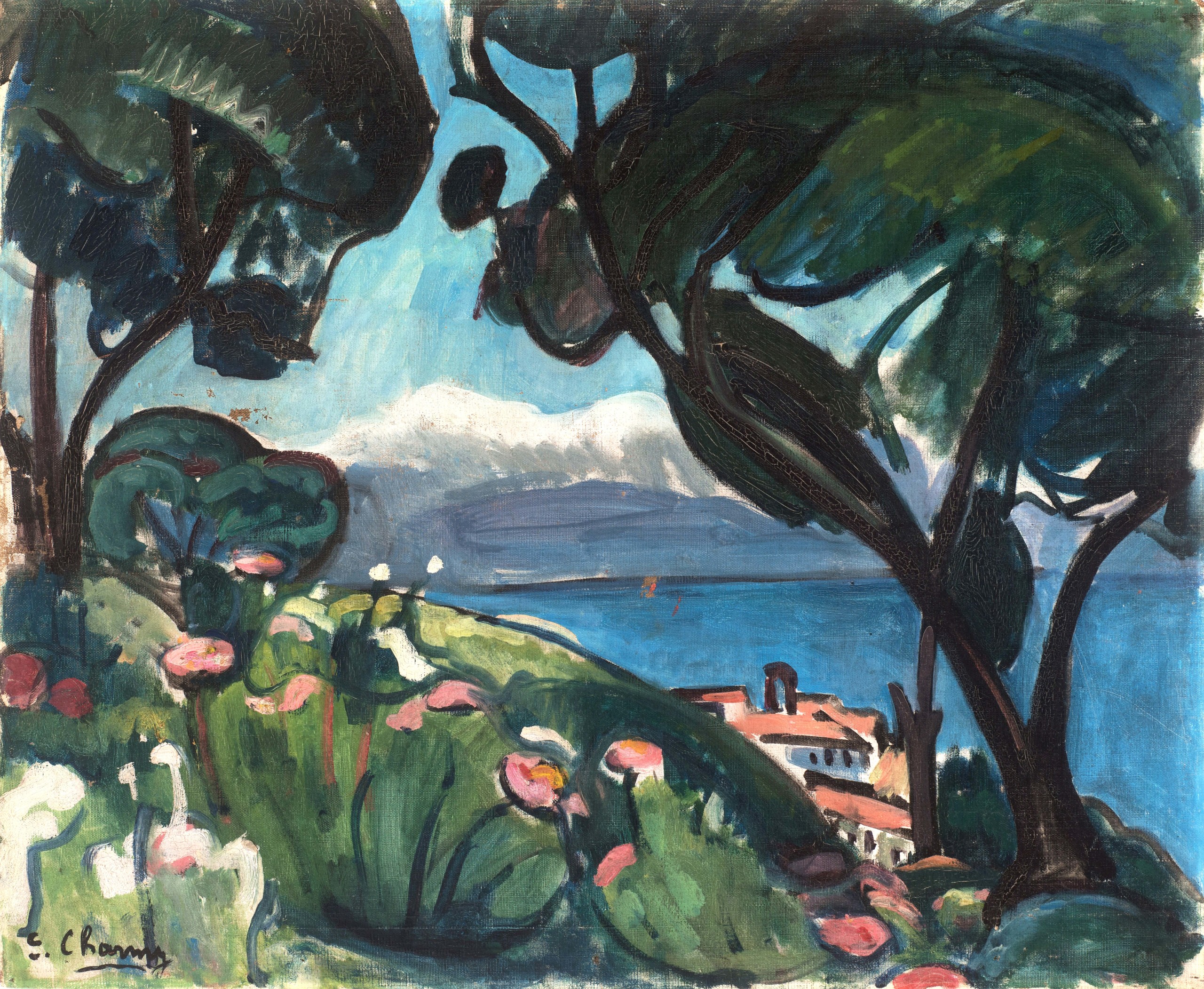

“Piana Corsica” by Émilie Charmy, 1906, oil on canvas mounted on board, 21-1/8 by 25-3/8 inches. Galerie Bernard Bouche, Paris ©Alberto Ricci.

There is no painter better equipped to capture the spirit of Weill than Charmy. Like Weill, Charmy was an outsider. She began exhibiting work at the same time as the Fauves but kept herself apart. “People mistook her reserve…for pride or disdain,” Weill writes of Charmy in her memoir. “If being proud means not shaping yourself to a pleasing, ready-made formula, if being proud means never deviating from your chosen line of conduct in art in order to fit your personality to fashion, then yes, she was very proud. And she had the kind of pride I greatly value.” Charmy and Weill became fast friends. Charmy’s paintings are fresh, self-assured, and quietly radical. At one point, she depicted herself while pregnant — “a daring image,” said Gumpert. “I think her works are amazing. I’ve only seen a few.”

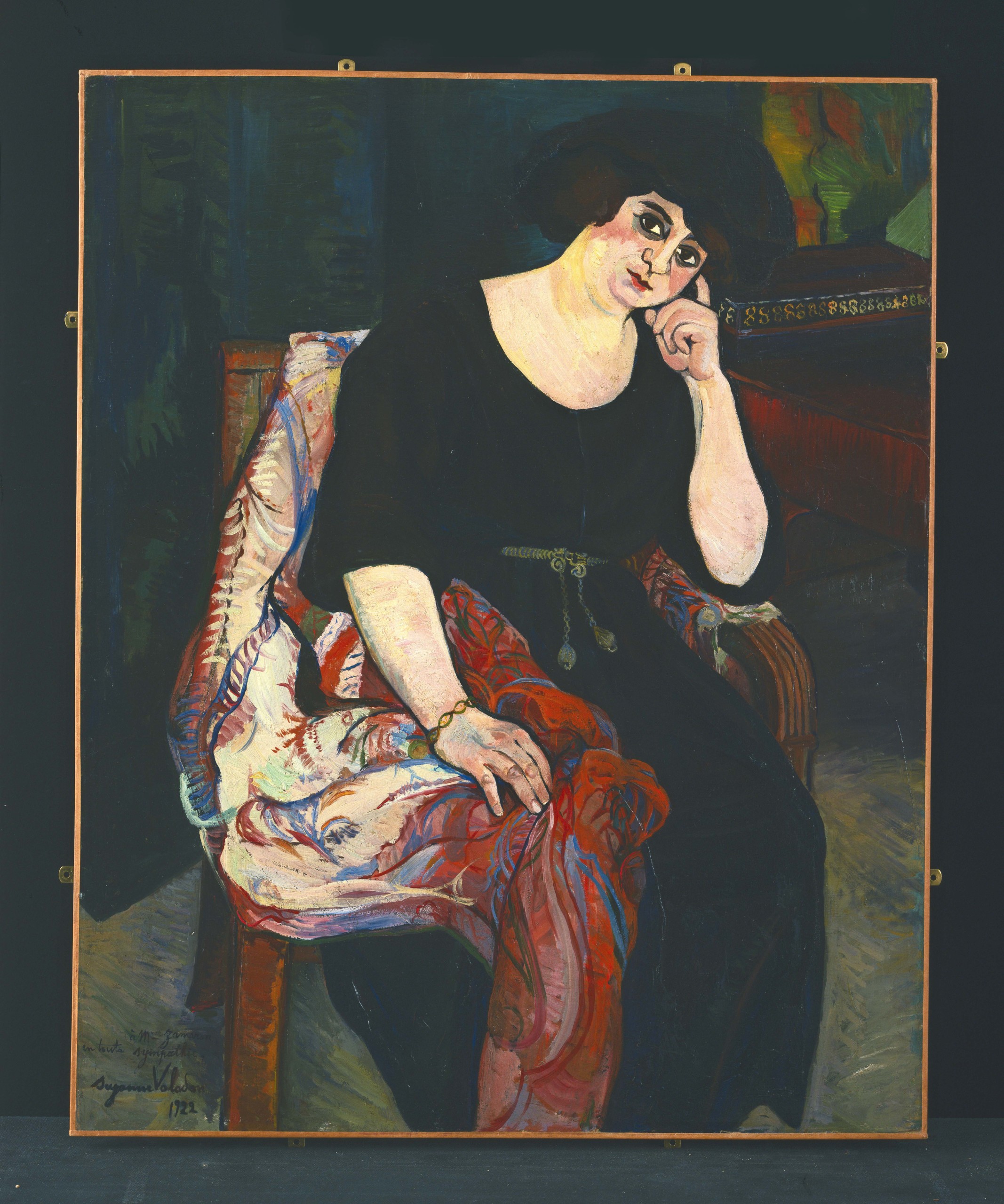

Charmy is one of several women artists represented in the show. A painting by Suzanne Valadon, “Portrait of Mme Zamaron,” is another highlight. In this rich, robust portrait, Valadon depicts her subject in a chair with a luxurious textile bunched around her. Valadon’s style is linear, muscular and luminescent. She paints as if she were drawing, quickly describing the fabric’s pattern with fresh, lively strokes. The warm fabric and Madame Zamaron’s fingers and cheeks glow against the painting’s darker corners, causing the entire canvas to radiate heat, as if lit by firelight. Valadon was not only a painter, but a model who posed for Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, among others. Her inclusion in the show reminds us that the artistic community of early Twentieth Century Paris was not made up of artists working in isolated studios, but a vast social network built on collaboration and social currency.

“Claudine Resting” by Jules Pascin, 1913, oil on canvas, 31-7/8 by 23-5/8 inches. Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Mr and Mrs Carter H. Harrison, 1936.11 ©Art Institute of Chicago, dist. GrandPalaisRmn/image Art Institute of Chicago.

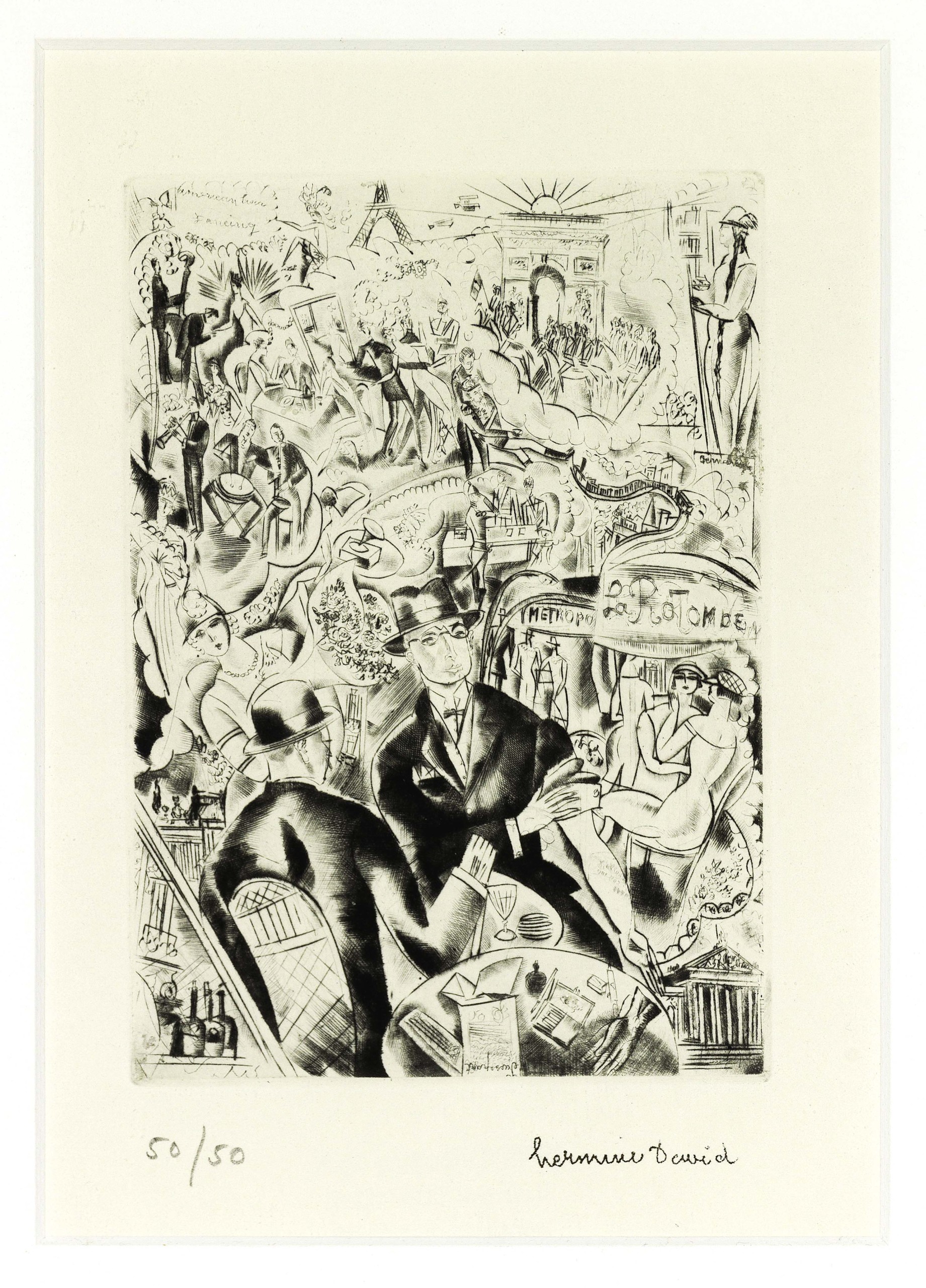

The exhibition also nods to the relationship between Hermine David and Jules Pascin, a married couple, both artists in Weill’s circle. Weill met Pascin in 1910 and exhibited his work in 23 shows across two decades. When Pascin married, Weill took on David as well. The show’s single work by David is a raucous drypoint depicting a dense, whirlwind scene of Montparnasse nightlife: jazz bands, cabaret dancers, gossiping couples, liquor and cigarettes. The energy of the image recalls a passage from Weill’s memoir, in which she describes a celebratory evening at David and Pascin’s apartment on Boulevard de Clichy: “People served themselves generously, hungrily, piggishly… It was turning into an orgy; time to leave.” One of two works by Pascin shows a different dimension of his wife. His “Portrait of Madame Pascin (Hermine David)” depicts David in a soft, dreamy reverie, her eyes closed and hands clasped at her cheek as she rests her elbow on a table.

Other highlights include a bronze sculpture by Meta Vaux Warrick, an African American artist from Philadelphia, who studied with Auguste Rodin. Warrick was a poet, artist, set designer and suffragette who made bold sculptural depictions of racial injustice, including a work that depicts the lynching of Mary Turner. Warrick was shunned by the American circles but embraced in Paris. The bronze on view at the Grey, “The Wretched,” is a composition of sinewy bodies in a harrowing throng reminiscent of a Last Judgement scene. Weill showed the work in a 1901 exhibition at her gallery. It is the only early work of Warrick’s to survive; the rest were lost in a studio fire.

“The Wretched” by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1901, bronze, 17 by 21 by 15 inches. Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Wash. Gift of Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, 1951.07.264.

As one surveys the works in “Make Way for Berthe Weill,” one can’t help but be scandalized that such a vivacious, self-assured and beloved gallerist at the center of the Parisian avant-garde could be so easily forgotten. Gumpert has theories on her exclusion from mainstream art historical narrative. In 1908, the prominent gallerist Ambroise Vollard criticized the tastes of Count Isaac de Camondo, who had recently made a stir by bequeathing his collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings to the Louvre. Weill rallied to Camondo’s defense by printing a pamphlet critiquing Vollard. Vollard, as retribution, eliminated Weill from his memoir entirely. “In my mind, that’s when the re-writing of history begins,” said Gumpert.

Gumpert hopes the exhibition will be an important step in setting the art historical record straight. The show will be of particular interest to art history students in search of new research areas. Many of the artists, like Charmy, are understudied and ripe for scholarly appraisals. In 2022, the University of Chicago Press published an English edition of POW! Right in the Eye, edited by Gumpert and translated by William Rodarmor (“Weill’s prose rhythm is closer to Machine Gun Kelly than Marcel Proust,” writes Rodarmor in his delightful introduction). The book’s appendices include a micro-biographies on the nearly 500 artists, collectors, socialites and bon vivants that Weill name-drops in the memoir, a veritable roadmap for any student looking for a new archival rabbit hole.

The last decades of Weill’s life are hazy. In 1941, with anti-Semitism on the rise, Weill was forced to close her shop but managed to escape deportation. Several of her artists, like Sophie Blum-Lazarus and Otto Freundlich, were deported to camps and executed. By the end of the war, Weill was frail and destitute. As a testament to her beloved status in the art world, a group of artists and gallerists held an art auction for her benefit, raising the equivalent of $130,000, enough to sustain her until her death in 1951. Her admirers were many. They called her “Mère Weill,” or “Mother Weill,” an affectionate play on words — in French, “Mère Weill” sounds no different than merveille, or “marvel.”

“Make Way For Berthe Weill” will be on view October 1-March 1. The Grey Art Museum, at New York University, is at 18 Cooper Square. For information, 212-998-6780 or www.greyartmuseum.nyu.edu.