![The firm of Disston & Morss produced this elaborately decorated and gold-plated measuring instrument as a “show piece” for their display at the 1876 United States Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Combination square, level and protractor by [Henry] Disston & [Joab] Morss, Philadelphia, 1876. Brass, steel, gold plating.](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/disston-morse_combination_measure_1876_centennial_study.jpg)

The firm of Disston & Morss produced this elaborately decorated and gold-plated measuring instrument as a “show piece” for their display at the 1876 United States Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Combination square, level and protractor by [Henry] Disston & [Joab] Morss, Philadelphia, 1876. Brass, steel, gold plating.

By James D Balestrieri

DOYLESTOWN, PENN. – “Magnificent Measures! The Hausman-Hill Collection of Calculating Instruments,” the new exhibition at the Mercer Museum, invites discussion of the surprising things people collect and of the surprising number of people who collect them. To your humble correspondent, at any rate, collecting early measuring instruments does not seem particularly unusual or unique. Consider the background of collector Jim Hill, who, as the exhibition material states, “discovered an early love of science and mathematics, which inspired an interest in calculating devices.”

Hill not only collected what he loved but what he went on to do. The exhibition material goes on, “These objects, it seemed to him, were more than simply tools or mechanical artifacts. To Hill, they were ‘significant, physical manifestations of how Math and Science have long been applied to everyday life.’ Later, Hill’s professional career as a machinist, metalsmith, woodworker, restorer and custom manufacturer soon became intertwined with his collecting interests.”

So collecting calculating devices may not be unusual. But what is true is that we take measurement and the tools we use in measurement for granted. They are part and parcel of everything we do, from pumping gas to mixing pancake batter. Industry would not exist – indeed, it could not exist – without standard measurements and instruments to determine those measurements.

.jpg)

Left, the “Adjust-o-matic” dress form by Luigi Cella (inventor), American, circa 1960s. Cellulose and metal. Right, adjustable tailor’s patterns by John B Plant, Manchester, N.H., circa 1910. Wood, cardboard, metal, fabric and paper. Photo Kevin Crawford Imagery LLC.

Instruments are how we apply math and science to life. They embody the practical applications that determine the angle of a roof, the length of a hem, the boundary of a parcel of land, or of a nation, our position on land and sea, the direction we travel in – or the direction we ought to travel in – down to the key I am at present pressing to make the letters that make the words on this page.

Let me give you a recent example of an incident in which faulty measurement led to disaster. Forgive me if you know this story, but in 1998 the Mars Climate Orbiter either flamed out in the Martian atmosphere or spun out of orbit and is now a small part of the solar system. Why? After an investigation, NASA’s software, calibrated in metric units, didn’t jive with the Lockheed-Martin spacecraft’s English (or imperial) measurements. The centimeter and the inch – like oil and, well, some other kind of oil. Result: $327,000,000 later – no Orbiter. All because of a failure to decide on a standard and make measurements based on that standard.

Let’s flip the calendar – yet another, at times contentious tool of measurement – back to the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century instruments, devices, tools, in the Hausman-Hill Collection.

.jpg)

Anthony Lamb cast this particular compass from reclaimed or “recycled” brass scrap, for which he offered “ready money” in a 1745 advertisement. The compass face is hand-engraved, displaying the four quadrants, 0 to 90 degrees. Surveyor’s compass by Anthony Lamb (1703-1784), New York City, circa 1735. Brass, glass, steel. Photo Kevin Crawford Imagery LLC.

Here’s the paradox: in order to facilitate the Industrial Revolution, machines had to be made of interchangeable parts in order to perform repeatable tasks. Instruments had to be made to help accomplish this. Yet, and this is the tricky part, there were no instruments to make those instruments and, until the widespread adoption of the English system of measurement and the advent of the metric system, no generally accepted standards of measurement. It’s a chicken and egg problem. The underlying message of the Hausman-Hill Collection is the tribute it pays to people who, by hand, created some of the instruments that challenged and eventually displaced humanity’s “handmade” epoch.

Cory Amsler, vice president of collections and interpretation at the Mercer Museum, hints at this paradox, writing, “The Mercer Museum is thrilled to present this stunning assemblage of early and often rare measuring tools from a local Bucks County collection. Jim Hill and Kathryn Hausman follow in the footsteps of Henry Mercer in appreciating the workmanship, scientific complexity and artistry involved in the manufacture of these remarkable pre-industrial age instruments.

“‘Magnificent Measures! The Hausman-Hill Collection of Calculating Instruments’ includes instruments for measuring the weather (thermometers, barometers), land (surveying instruments), and the human body (a tailor’s ruler and other implements for gauging the size of arms, legs, waists, feet, heads and fingers for crafting clothing and accessories).

.jpg)

When Congress established a commission in the 1850s to conduct a survey of a portion of the northern boundary of the United States, a number of William Würdemann’s instruments were selected to accompany the survey team. The commission completed its work in the 1870s, which was summarized in a report authorized by President U.S. Grant. The Northern Boundary survey team carried and employed this actual instrument in its 1870s expedition. The device — numbered “71” by Würdemann — is specifically referenced in the commission’s 1877 report. Right, theodolite or geodesic transit #71 by William Würdemann, Washington DC, circa 1870. Brass, glass, wood. Photo Kevin Crawford Imagery LLC.

“The exhibit showcases the work of significant early makers of measuring implements, such as notable Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century craftsmen Anthony Lamb, Rufus Porter, Thomas Greenough, Justus Roe, Caleb Leach and the Chapin Family of Connecticut. Historic photographs and documents of these makers and their businesses add to the exhibit’s appeal.”

The functionality of these tools is beyond question. You can see how well – and long – some of them saw service.

Beyond function lies the sheer beauty of these objects, as if they were made, not just with utility in mind, but with eye appeal, curb appeal and an intent to convey an understanding of materials, how to shape them, combine them and create something new that could get something done and look good doing it.

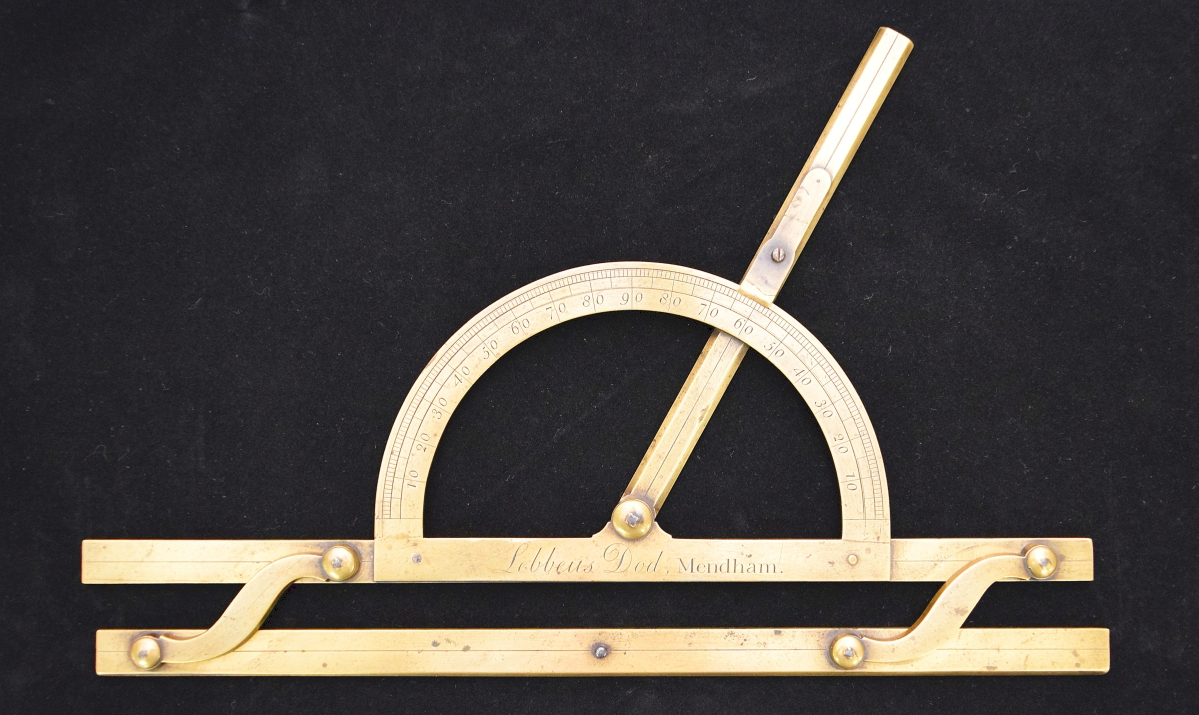

Have a look at the 1876 Combination Measure fabricated by the Philadelphia company Disston & Morss in honor of our nation’s centennial. An ingenious blend of retracting ruler and a protractor, the tool is made from solid brass and steel. What grabs the viewer isn’t the ingenuity of the thing, it’s the deep engraving along the sides of the Combination Measure. The scrollwork is exquisite, deeply incised bulbous acanthus curves and arabesques you would expect to find on the sideplates of the finest double-barreled shotguns. The piece speaks to something deeply human, a trait that goes way back in the archaeological record: the desire to adorn even the most functional tools and objects.

This is the earliest known mathematical instrument made in the American colonies. The unique instrument retains remarkable early repairs to its glass. The wood block-printed compass card is hand colored. Surveyor’s compass by Joseph Halsy, Boston, circa 1690. Wood, glass, paper.

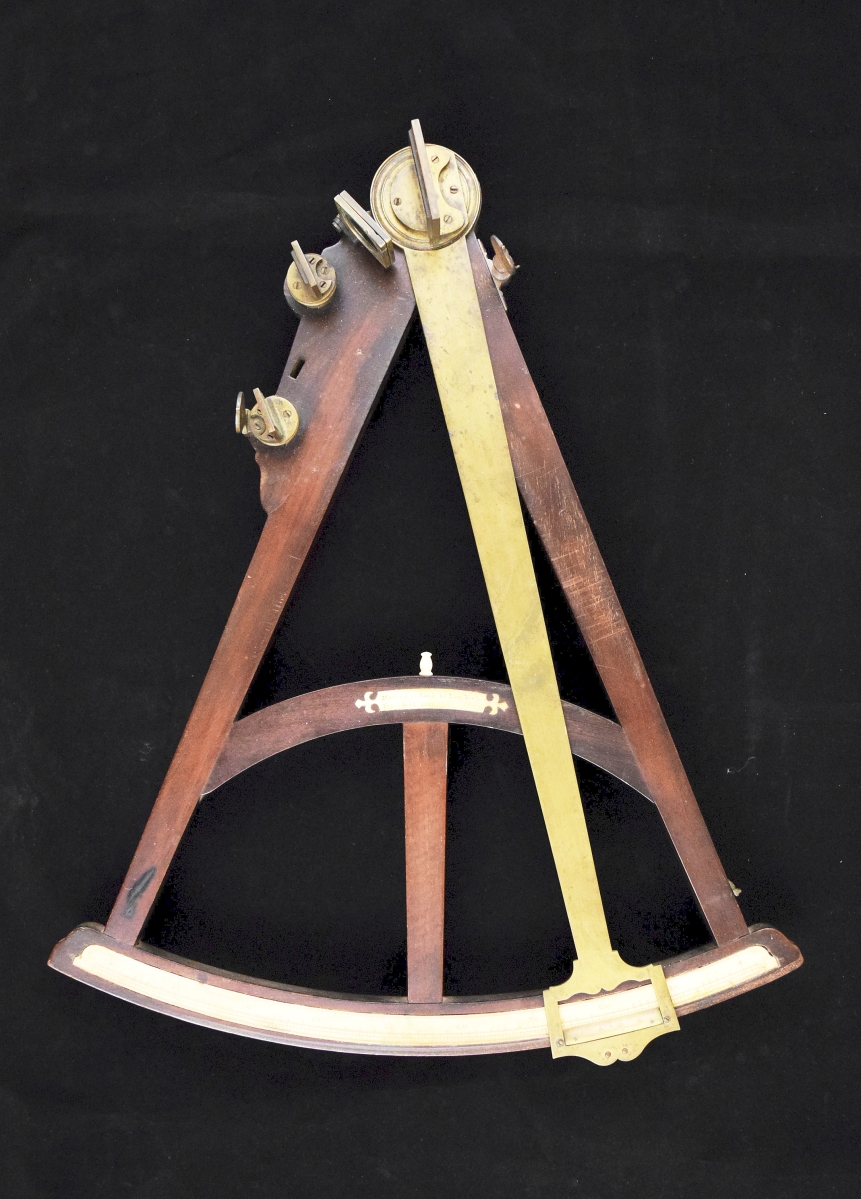

Once you begin to notice this, it’s everywhere in the exhibition. An Eighteenth Century Thomas Greenough surveyor’s compass, or circumferentor, retains the beautiful patina of the wood, but the brass object and eye vanes boast Chippendale curves and the compass face itself is decorated with a fleur-de-lis, sailing ships, a lighthouse and a flock of circling seagulls. The nautical decoration is curious since the surveyor’s compass is used to measure horizontal angles on land. By comparison, the Halsey compass, made in 1690, is of simpler design, but the compass rose in the center of the face is an actual rose, elegantly drawn and printed. These decorations speak to this era of exploration, confidence, and the optimism that humanity, through science, could begin to parse, map and exploit the resources of the entire surface of the Earth. For Indigenous Peoples the world over, of course, these devices and the lines on paper that derived from them held little meaning at first but would come to have devastating consequences.

The determination of longitude is one of the great stories in science. Dava Sobel’s book, Longitude, tells the tale wonderfully. As the need to establish longitude became ever more pressing, the theodolite replaced the surveyor’s compass. A historic example of this instrument, Geodetic Transit #71 made by William Würdemann in Washington DC circa 1870 is one of the highlights of the exhibition: “When Congress established a Commission in the 1850s to conduct a survey of a portion of the northern boundary of the United States, a number of Würdemann’s instruments were selected to accompany the survey team. The Commission completed its work in the 1870s, which was summarized in a report authorized by President U.S. Grant. The Northern Boundary survey team carried and employed this actual instrument in its 1870s expedition. The device – numbered ’71’ by Würdemann – is specifically referenced in the Commission’s 1877 report.”

The beautiful tableau of the two workmen that adorns the center of the Rufus Porter inclinometer – labeled a “Plumb & Level Indicator” – advertises itself, depicting one worker lifting a board with a rod while the other watches a level, this level in fact. Not only does the image show the Plumb & Level Indicator at work, it shows the viewer an example of how the device is to be used – the instrument is, in a way, its own instruction manual. Now, in its own aged wood frame, this working object in the Hausman-Hill Collection becomes a window into the past even as it transforms into a work of art.

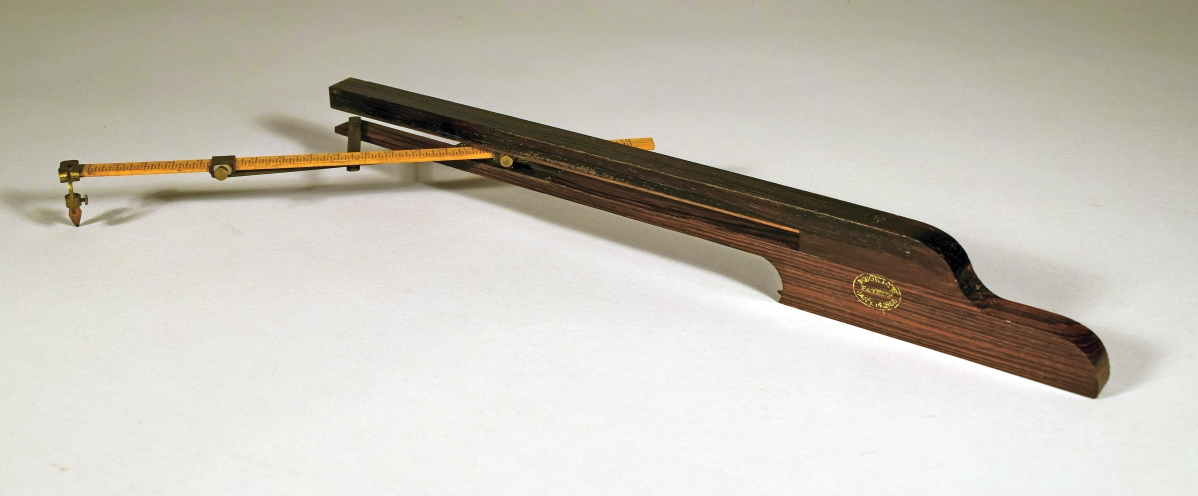

Originally patented by Franklin Bowly of Winchester, Va., this device was produced by the Chapin Company. The Ellipsograph was designed for drafting or laying out elliptical shapes. Ellipsograph by H. Chapin’s Son Co. (E.M. Chapin), Pine Meadow, Conn., 1868. Rosewood, boxwood, brass.

Other objects might be more humble yet they are nevertheless of great interest. For example, scales and curves that defy understanding cover Studabecker’s Tailor’s Square. The teardrop shape of the opening in the middle of the device seems to be able to measure the neck and shoulder, and to place darts in a dress or gown.

In their fascinating book, The Culture of Diagram, authors John Bender and Michael Marrinan describe how applied mathematics requires a cognitive leap correlating the abstraction of mathematics with the forces, features and elements of the real world and delve into the paradigm shift that begins in the Eighteenth Century with the advent of calculus and the study of probability. It wasn’t enough to see the world anew. Science had to have instruments to measure and confirm observations on scales large and small. The practical applications of these instruments ushered in the Industrial Revolution and transformed the world. As we begin to assess the consequences of that revolution, “Magnificent Measures! The Hausman-Hill Collection of Calculating Instruments” is a timely and important exhibition.

I refer you back to the Mars Climate Orbiter disaster and leave you with a famous thought, one which is true whether you are sending a rocket into space, adding a deck to your house or hemming a skirt: measure twice; cut once. And when you measure, make sure you measure with the right device.

The Mercer Museum is at 84 South Pine Street. For more information, www.mercermuseum.org or 215-345-0210.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)