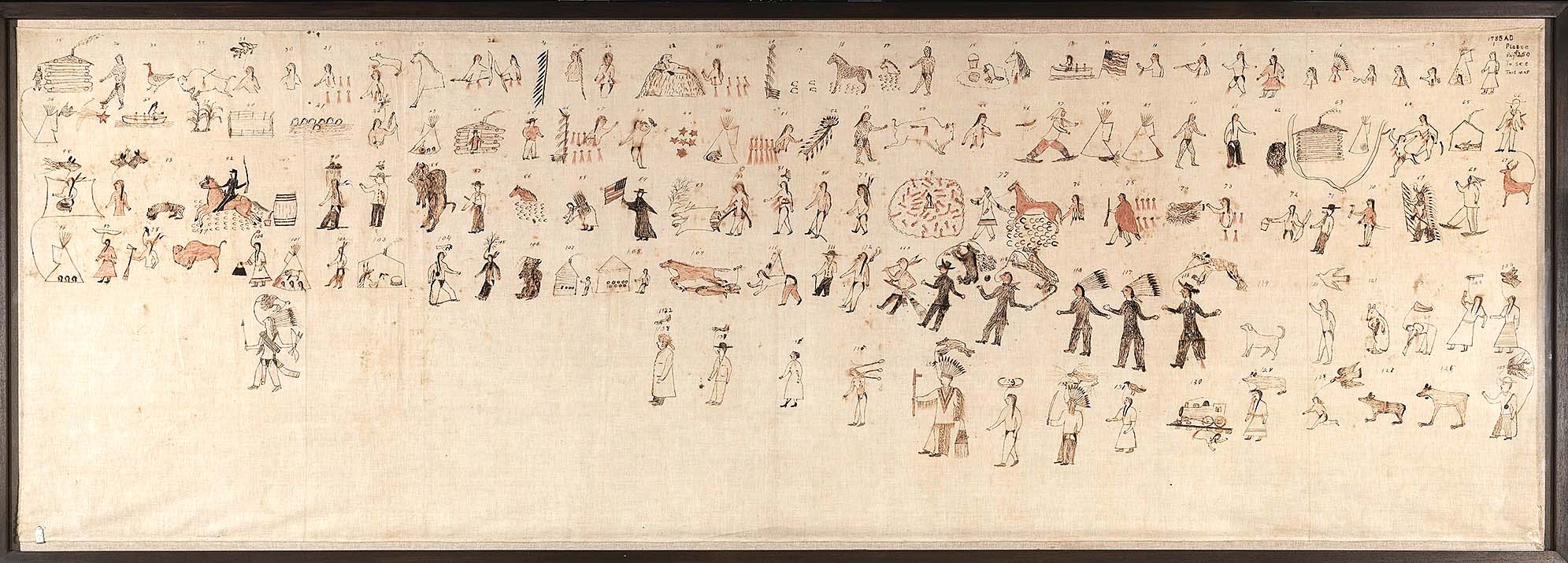

“Winter Count” by Joseph No Two Hornsor He Nupa Wanica (Hunkpapa Lakota, Teton Sioux, 1852-1942), circa 1922, ink, watercolors, and crayon on muslin; 93 by 36 inches. Jo Anderson, Omaha, Neb. Photo: Jeffrey Wells.

By Laura Beach

BENTONVILLE, ARK. — With the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence rapidly approaching, institutions across the United States are scrambling for approaches to celebrating that move beyond the tired tropes of the Bicentennial. While many will look for inspiration to the federal project America250 (www.america250.org), others may find a perfect paradigm in “Knowing the West.” Symphonic by design, this ambitious, imaginative and ultimately unifying presentation at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art brings diverse voices together to enunciate a new American truth, one that is both nuanced and broadly inclusive.

The project’s success owes much to the inspired vision and organizational talents of Mindy N. Besaw, Crystal Bridges’ curator of American art and director of research, fellowships and university partnerships, and Jami C. Powell (Osage), associate director of curatorial affairs and curator of Indigenous art at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H.

Deftly deploying more than 120 superlative examples of Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century textiles, baskets, paintings, pottery, sculpture, beadwork, saddles and prints by Native American and non-Native American artists, the curators unspool a complex tale, one juxtaposing themes of aggression, resistance and defiance against others of exchange, collaboration and union. More narrowly, organizers gently dismantle what one might call Occidentalism, in this instance the collection of myths and imagery born of the exoticization of North America’s original inhabitants by European Americans, who — guided by the tenets of Manifest Destiny — assumed that the American West was vast, unclaimed and theirs for the taking.

Plateau women’s bag, Underwood family, likely Ellen (Wasco/Yakima, act. Nineteenth Century), circa 1890. Glass beads, cotton thread, Native-tanned leather, silk cloth, 10¾ by 7½ by ¼ inches. Collection of Gaylord Torrence.

Co-curator of Crystal Bridge’s landmark 2018-20 traveling exhibition “Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now,” Besaw began contemplating what would become “Knowing the West” more than a decade ago. Three years ago, she reached out to Powell, whose work on the 2022 Hood Museum display “This Land: American Engagement with the Natural World” Besaw admired. The Hood Museum, an important source for historic and contemporary Native American art, became a major lender to “Knowing the West.”

Besaw and Powell assembled a curatorial advisory council to consult on every aspect of “Knowing the West.” Besaw reflects, “Because we wanted to talk across disciplines and traditional categories we sought advisors with varied expertise. For example, contributor Michael R. Grauer of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum is an authority on saddles. As it turns out, the saddle is ideal for conveying some of our main ideas about cultural interchange and influence because there is deep variation within the form.”

Zeroing in on the challenge at the heart of the current presentation, Powell asks, “How do you know the West? What does the West mean to you? Who gets to tell stories about the West? How have images shaped your view of the West?” She adds, “We are trying to tell really complicated histories and stories, but to also invite people to bring their own understandings into this experience and to engage them in a dialogue throughout the exhibition. We ask these questions multiple times as a way of layering on new meanings, understandings and visual experiences as visitors move through the galleries.”

Blackfeet doll with horse, dress and miniature cradleboard, artist once known, 1870-90, leather, beads, wool, sticks, horsehair, 6¼ by 6 inches. Courtesy of the Kansas City Museum and Union Station Kansas City, Kansas City, Mo.

The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue — the latter featuring essays by editors Besaw and Powell, plus 19 other contributors — are organized around the themes of “Origins,” “Authority,” “Persistence,” “Nation Building” and “Rethinking.”

In the show’s opening sequence, “Origins,” the curators abandon a conventional chronology of the American West, one usually tied to the expansion and completion of the transcontinental railroad. They feature instead an extraordinary watercolor, ink and crayon drawing on muslin by Joseph No Two Horns/He Nupa Wanica (Hunkpapa Lakota, Teton Sioux, 1852-1942). Dating to circa 1922 and called a “winter count,” the 96-inch-long pictorial record documents the years 1785 to 1922 through Lakota eyes in a way that is “community-centered and relational,” as Besaw puts it.

In “Authority,” the curators ask who speaks for the West, and, more pointedly, who defines its artistic hierarchies. The monumental canvases of Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) — here represented by the transcendent “Sierra Nevada Morning” of 1870 — depicted the West in all its physical splendor. But as Tuscarora art historian, artist and curator Jolene Rickard has argued, “From an Indigenous perspective, the genre of landscape painting is one of the conceptual and visceral tools of colonization.”

“Sierra Nevada Morning” by Albert Bierstadt (American, born Germany, 1830-1902), 1870, oil on canvas, 55¼ by 85½ inches. Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Okla.

If history favors the victors, then art history disproportionately affirms the privileged. The curators seek to redress inherent bias by revising labels to read “artist once known,” explaining, “There are many Indigenous artists in this exhibition who were well known in their communities, but whose names and identities are no longer known to us today because they were not recorded by those who acquired their artworks.”

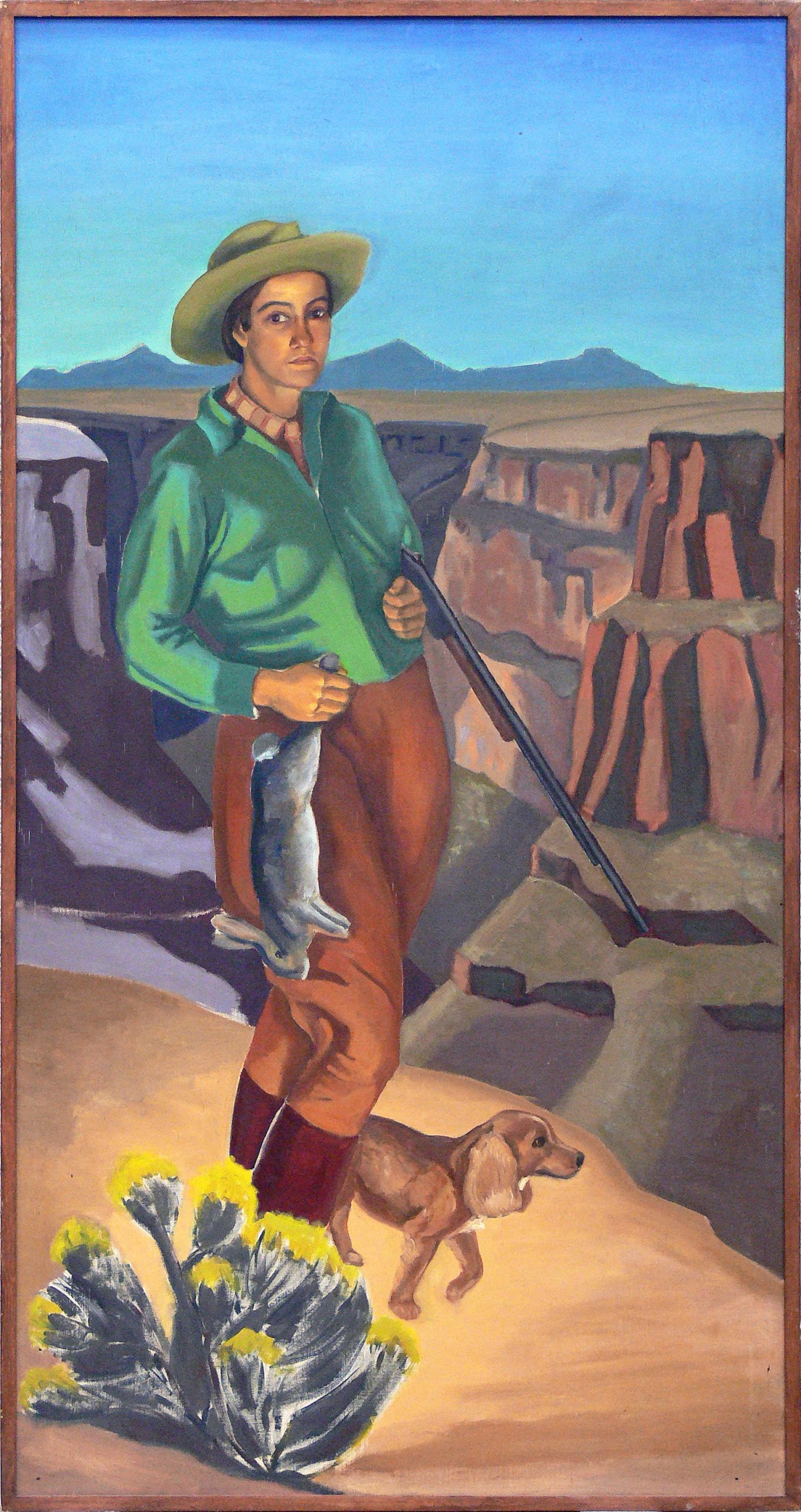

The curators are likewise keen to spotlight overlooked women artists of all heritages. Visitors will marvel at the virtuosity of basket weavers Elizabeth Hickox (Karuk/Wiyot, 1875-1947) and Louise Hickox (Karuk [Karok], 1896-1967). They may also admire “Desert Indian,” a 1932-37 oil on canvas by Taos, N.M., resident and D.H. Lawrence confidante Dorothy Brett (1883-1977). The work is both stylistically self-assured and emancipated from stereotype.

In “Persistence,” organizers explore themes of artistic adaptation and resilience as cultures collided on the North American continent. Visitors encounter not only Native American art of the post-contact era — Osage wedding attire fashioned from repurposed US military jackets and top hats is one fascinating example — but also consider work from other cultural groups. New Mexico’s vibrant santero tradition is reflected in “La Santisima Trinidad,” a devotional sculpture by José Rafael Aragón (active 1826-55). A two-gallon jug by H. Wilson & Co., circa 1869-84, honors a pottery founded in Texas by three emancipated Black men. As Besaw and Powell explain, “Migration of peoples, ideas, goods and art forms shaped images of the American West.”

“La Santisima Trinidad” by José Rafael Aragón (active present-day New Mexico, 1826-1855), circa 1826-55, wood, 22 by 16 by 8 inches. Tia Collection, Santa Fe, N.M. James Hart Photography.

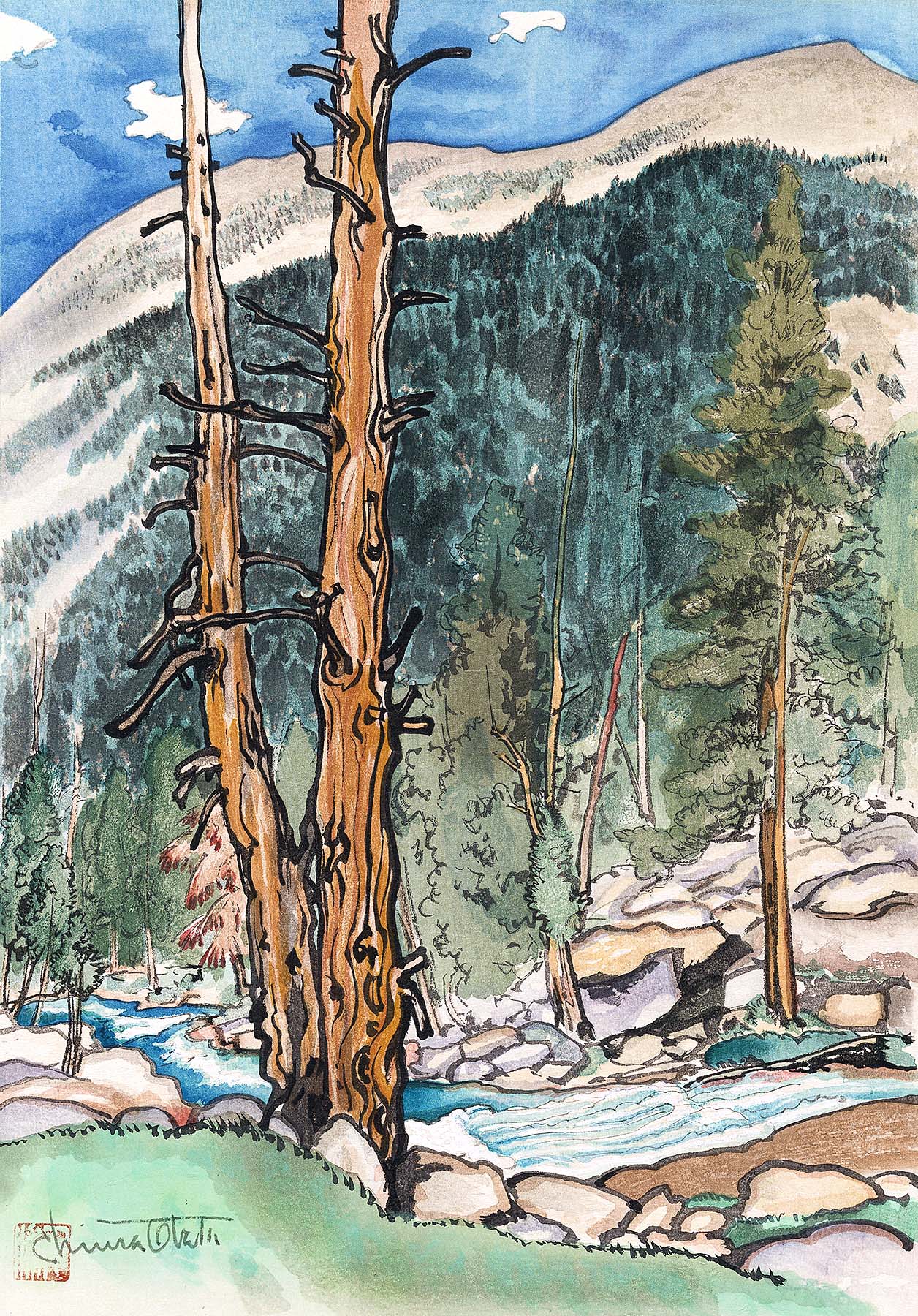

In “Nation Building,” organizers survey art, some of it commissioned by the US government, meant to foster visions of a heroic American landscape stretching from coast to coast. The curators cite, among others, painter Thomas Moran (1837-1926), who accompanied the first US geological expedition to Yellowstone in 1871. In counterpoint, they offer depictions of America’s natural wonders by Japanese-American artist Chiura Obata (1885-1975), a UC Berkeley professor who spent three years incarcerated in government internment camps during World War II.

Nationhood means something altogether different for Native Americans, who maintain some governmental sovereignty. An array of beaded and quill-decorated cradleboards, for instance, speaks to the preservation of cultural traditions by successive generations of Indigenous people, members of tribal nations that are distinct from one another.

Infused with nationalistic ideas, as Madison BlueJacket Cáceres (Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma) writes, paintings such as W. H. D. Koerner’s (1878-1938) “Madonna of the Prairie,” published on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1922, depict the prototypical “pioneer woman” as a “figure of moral uprightness, of quiet sacrifice, and above all, of domesticity.” Paradoxically, such images helped whitewash the truth of US policies that forced Indigenous families off their land and their children into boarding schools.

“Madonna of the Prairie” by W.H.D. Koerner (American, 1878-1938), 1921, oil on canvas, 43½ by 35½ inches. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyo.; museum purchase, 25.77.

The exhibition’s concluding section, “Rethinking,” presses visitors to reconsider the American West, shown at Crystal Bridges in all its ambiguity. Besaw notes the skill with which Frederic Remington (1861-1909), working from props in his New York studio, depicted the West in ways that, while once admired for their realism, now invite question. Of “Shotgun Hospitality,” a 1908 canvas originally assumed to depict a cowboy warily accommodating three Native American interlopers, she writes, “If we examine Remington’s work within the legacies of colonialism and the realities of encounter and exchange on the Nineteenth Century western Plains, we can counter the painting’s previously prevailing narrative. Given the title, for example, one can ask: Who is hosting whom in this prairie encounter?” Assumptions persist, but as Besaw writes, “It is time to interrogate them.”

“Framers” for a new age, Besaw and Powell set the parameters for an updated history of American art that, departing from much recent museum practice, joins Native American and non-Native American art in one panoramic display. As Besaw notes, “Art of the West is so often presented in simplified and binary terms — such as ‘cowboys and Indians’ — which does little to embrace the multiplicity of artists and communities in the West.”

“Upper Lyell Fork, Near Lyell Glacier” by Chiura Obata (American, b Japan, 1885-1975), from World Landscape Series “America,” circa 1930, color woodcut, 15¾ by 11 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Ark., 2023.34. Photography by Edward Robison, III.

Powell reflects, “Our hope is that this exhibition can be an example of what is possible when we engage in really difficult conversations and push ourselves to look at historical works of art in new ways.”

“Knowing The West” travels to the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Jacksonville, Fla., and the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, N.C., following its close at Crystal Bridges on January 27.

Crystal Bridges is at 600 Museum Way. For information, 479-418-5700 or visit www.crystalbridges.org.