“Procession in Piazza San Marco” by Cesare Vecellio, 1586-1601, oil on canvas, 52¾ by 76-3/8 inches. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia — Museo Correr.

By James D. Balestrieri

NASHVILLE — “Doge,” though it is derived from an acronym, is a big word these days, having to do with the slashing of government. However, for the thousand-year period between 698 and 1798, when Venice was an independent republic, the Doge — a word derived from the Latin dux, or leader — was the elected head of the Venetian state as well as the leader of the oligarchy and was tasked with the expansion rather than the contraction of government. Venice was a thalassocracy, that is, a coastal, maritime polity whose power depended entirely on trade. The role of the Doge was, in part, ceremonial, overseeing, for example, the annual symbolic marriage of Venice with the sea. But ceremony and symbolism, as we shall see, became crucial to the Venetian persona. Despite their importance and nominal authority, doges, who were often merchants themselves, ruled under constant surveillance: they could not, for example, own property in foreign lands. From the Ninth through the Thirteenth Centuries, two tribunes were chosen to check the Doge’s power, making sure he hewed to the laws and acted on behalf of the people (full disclosure: these tribunes were called Balestrieri).

Once the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 and assimilated the Byzantine Empire into their own, Venice became the gateway to the riches and rich markets of the East. It was also the first point of friction between the Christian and Islamic realms. Venice, however, was small in comparison with the Ottoman Empire, relying on a powerful navy, the profit motive and nimble diplomacy. From this point on, the most important of the Doge’s functions was to project Venetian power, establishing trade with the Ottomans wherever and whenever possible while maintaining vigilance against the constant and inevitable clashes between the two as each reached out towards the other with colonial aspirations.

Doge Francesco Morosini’s corno ducale (ducal horn), Venetian artisanship, late Seventeenth Century, woven brocade; 8¾ by 9¾ by 6¼ inches. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia — Museo Correr.

Meanwhile, the Sultans, from their new capital, Constantinople, did the same. For four centuries, war and peace were the lungs of the Mediterranean. The two sides would inhale peace and hold their breath, only to find themselves gasping for air once again in bloody conflict. In the excellent catalog that accompanies the Frist Art Museum’s “Venice and the Ottoman Empire” exhibition, curator Stefano Carboni explains this succinctly: “The relationship between Venice and the Ottomans represents a fascinating and multifaceted chapter in the history of Mediterranean geopolitics, one marked by a blend of cooperation and conflict, handshake- and arms-length approaches, diplomacy and back-stabbing, understanding and misunderstanding.”

Yet, at the same time, as the mercantile classes in Venice and the Ottoman Empire bought and sold raw materials and finished goods to one another, each culture, rich in itself, borrowed heavily and synthesized the otherness of the other. It is this interaction and synthesis that forms the basis of “Venice and the Ottoman Empire.” Organized by the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia and The Museum Box, more than 150 objects from seven Venetian museums, ranging from ceramics, glass and metalwork, to paintings, prints and textiles, will be on display.

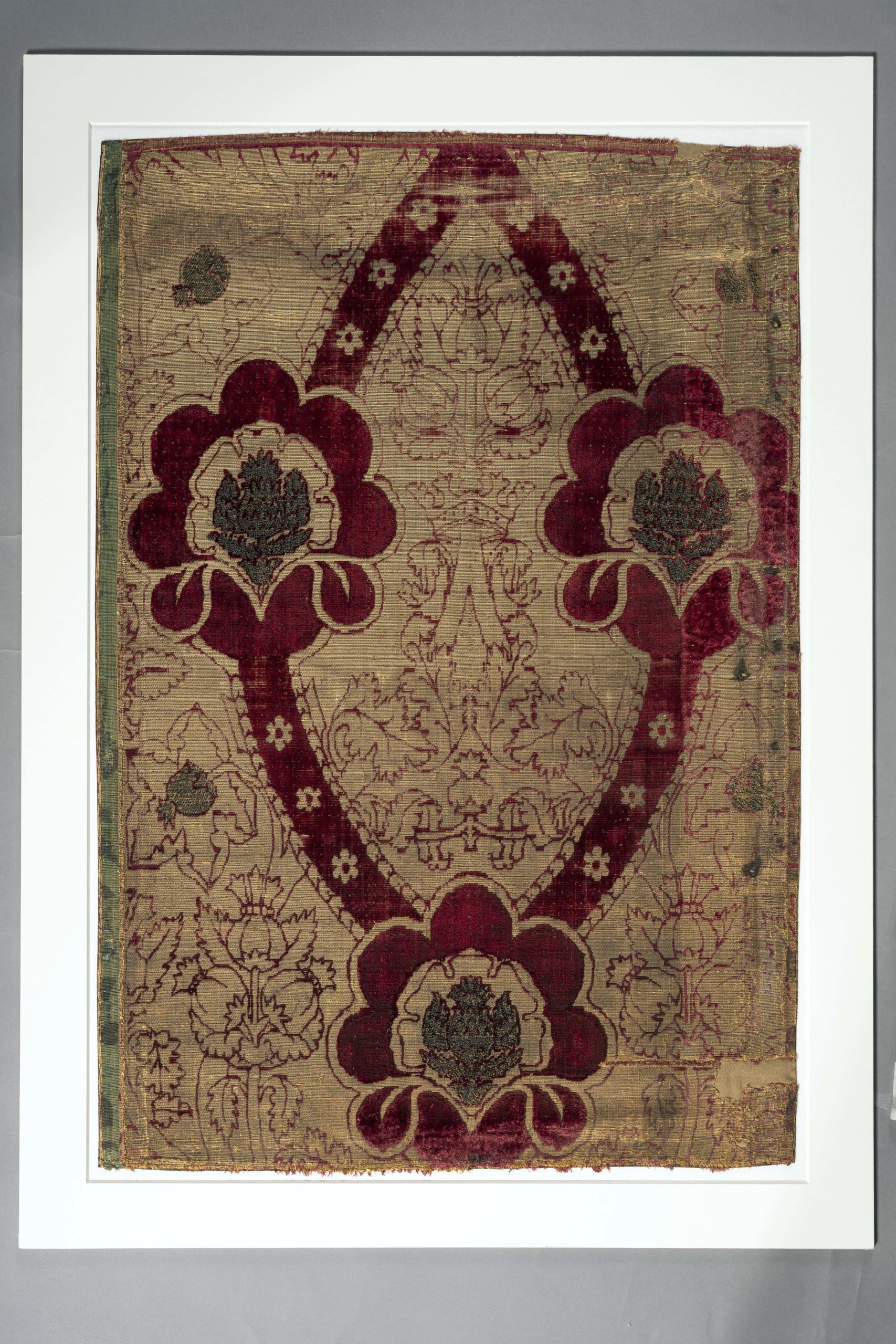

Venetian Renaissance painters, for example, incorporated Ottoman textiles into religious paintings and portraits. The catalog notes their “patterns with palmettes, pomegranate fruit and leaf motifs and spiraling stems, usually brocaded in gold, demonstrate the high regard for Ottoman textile design in Venetian society — a trend that reflects the broader cultural interaction facilitated by trade and the role of art in signifying social and economic prestige.” But these textiles also made their way into garments worn by secular rulers as well as carpets displayed by merchants in their homes and places of business. Painted between 1501 and 1505, Vittore Carpaccio’s “Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan” in a cloak of red and gold brocade, painted during a war which ultimately cost Venice the Greek region of Morea, or the Peloponnese, as we call it. The cloak and the traditional headgear of the office — the corno ducale — are fashioned of a golden brocade on red silk with floral patterns that are unmistakably inspired by Ottoman ornament.

Any precise meaning of this is hard — if not impossible — to unearth.

Bath clogs, Ottoman Turkish artisanship, Seventeenth Century, wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and studded leather, 2¾ by 9-1/8 inches. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia — Museo di Palazzo Mocenigo.

What one sees at a glance is this: In the portraits of doges and sultans, in peace and in war; in the Turkish bath clogs worn by a Venetian noble or merchant; in the intricately damascened brass spice bowls and in the gold thread woven into silk, the complexity of the ornamentation, of the weaving, is a metaphor for two cultures — European and Asian, Christian and Muslim — inextricably braided into one another, fates intertwined, even at those times when respect and fascination faded and fear erupted into conflict. In seven major wars between 1400 and 1800, Venice would lose most of its overseas territories. As Anastasi Stouraiti writes in his catalog essay, “Trade could not buy peace and, even in peacetime, Venice remained a colonial empire ruling over a chain of militarized, asset-stripping overseas bases that provided its war and merchant fleets with manpower and logistic support.”

In 1797, Napoleon conquered Italy and brought an end to the Venetian Republic. You would think Ottoman power would have ascended. Yet, afterwards, the power of the Ottoman Empire shrank until, after siding with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I, it would vanish altogether, giving rise to modern Türkiye. Mutual destruction is not unique to Venice and the Ottoman Empire.

Still, diplomacy as we know it, owes a great deal to the periods when cooler heads prevailed in Venice and Constantinople. Venice maintained a vast network of spies, assassins and agents throughout the Ottoman Empire — and all of Europe (read Casanova’s account of his time in Eighteenth Century Venice, for example). Placing great emphasis on gathering intelligence, even, perhaps especially on those with whom we are at peace, at least provisionally, the role of Venice in modern diplomacy is well documented, but new scholarship “pays particular attention to the role of the Ottoman empire in the development of key components of modern diplomacy, most importantly resident embassies, extraterritoriality and reciprocity.” In 1621, the Venetians created the Fondaco dei Turchi, a place in Venice where Ottoman traders could stay and do business. Similarly, the Ottomans established lavish diplomatic quarters in Constantinople. In each capital, dragomen, who were fluent in a variety of languages, did their best to keep the lines of communication open.

In addition to sections on overcoming communication barriers, decorative arts and textiles, the spice trade and ship building, the exhibition also highlights several other specific events and aspects of the relationship between the two powers.

“Doge Francesco Morosini offers Venice the Reconquered Morea,” after Gregorio Lazzarini, Nineteenth Century, oil on canvas, 70-1/8 by 50 inches. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia — Museo Correr.

One section focuses on the Gagliana Grossa, a Venetian merchant ship headed for Constantinople that sank in 1583 with a rich and diverse cargo of textiles, glass, jewels and other goods. A number of objects from the ongoing excavation of this highly significant archaeological find are on display. Another section focuses on Venetian naval commander and doge Francesco Morosini (1619-1694), whose seeming victories over the Ottomans helped Venice regain some of her overseas territories, especially those in Greece, and a good deal of her prestige. Morosini is perhaps best remembered as the commander-in-chief who ordered the shelling of the Parthenon, where the Turks had stored their powder and arms. Despite having committed one of the great crimes against art, Morosini took time from his campaigns to amass an important collection, some of which can be seen in the exhibition.

To show the enduring influence of Venetian and Ottoman textiles, a third gallery highlights the work of Mariano Fortuny (1871–1949), who developed new methods of printing that allowed him to create sumptuous fabrics that evoked the old crossroads of Eastern and Western design.

The last section, and a delightful one, describes the diplomatic feasts that the two great powers prepared for one another and reproduces recipes from some of the culinary fare that each adopted and adapted from the other.

Spice bowl with lid, possibly Mamluk Egyptian, Ottoman Anatolian or Western Iranian artisanship, last quarter of the Fifteenth Century, engraved brass, damascened in silver and gold, 2¾ by 5¾ inches. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia — Museo Correr.

Venetians, for example, took to riso turchesco (Turkish rice pudding) and the catalog reproduces a recipe for the dish adapted for the Lenten season. Other recipes reveal the Italian taste for Ottoman nut sauce and Turkish pilaf, while fritters appear to have appealed equally to palates in Venice and Constantinople.

Even Parmesan cheese served as one of the currencies that used to flatter, curry favor and purchase information. In her essay, “Shared Fortunes, Shared Foods,” Priscilla Mary Isin writes, “Gifts of food were another aspect of food diplomacy; the Ottomans customarily sent gifts of sweetmeats, fruit, and flowers as a gesture of welcome to Venetian ambassadors on their arrival, while the ambassadors presented the sultans with Parmesan cheese, which was a favorite at the palace. In 1608, the Venetian ambassador Ottaviano Bon reported that the Ottoman sultan, royal women and nobles preferred cheese from Lombardy and Piacenza to local cheese and ‘eat it with great gusto, especially when they go hunting and on pleasure excursions.’”

If you saw anything of the funeral of Pope Francis, you saw the cultural exchange between East and West, between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, in action. According to an expert quoted in an article in the May 4, 2025, edition of Turkiye Today, the carpet beneath the Pope’s coffin, also used during the funerals of Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, is of Turkish style, though woven in Iran. The article goes on, “These carpets weren’t just trade goods — they were powerful diplomatic tools, symbolizing mutual respect between East and West.” They are “believed to bring peace and closeness to the divine.” and speak to the long tradition of textiles, especially carpets, as emblems of cultural diplomacy.

Has an exhibition about events that took place centuries ago ever been more timely than “Venice and the Ottoman Empire”? It doesn’t take a doge, or a sultan — or a tribune — to answer that question.

“Venice and the Ottoman Empire” is on view at the Frist Art Museum from May 31 through September 1.

The Frist Art Museum is at 919 Broadway. For more information, 615-244-3340 or www.fristartmuseum.org.