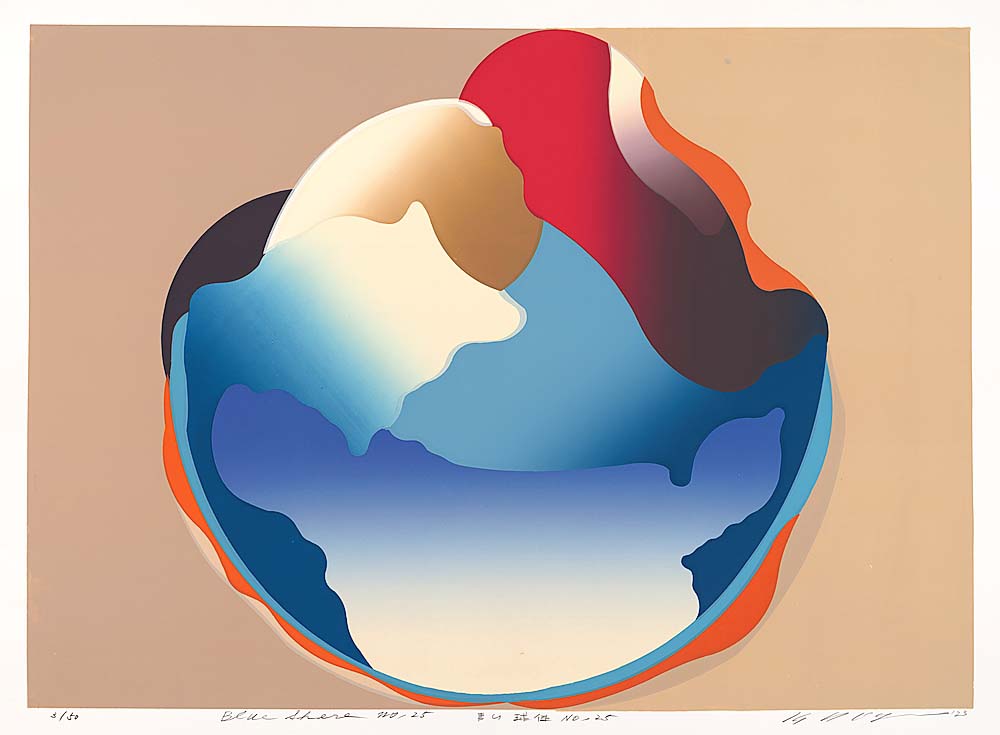

“Blue Sphere No 25” by Koichi Ogawa, 2023, silkscreen, edition of 50.

By Kristin Nord

FALMOUTH, MASS. — This summer has marked the return of a juried show of leading Japanese printmakers at Highfield Hall & Gardens, for the third collaboration with the College Women’s Association of Japan (CWAJ) and a special exhibition that showcases the prints of five post WWII-era women pioneers.

This exhibition, “Trailblazers: Celebrating Contemporary Japanese Prints,” has been made possible in part through the support of The Japan Society of Boston, The Falmouth Fund, The Falmouth Road Race Foundation, the Cape Cod 5 Charitable Endowment, The Woods Hole Foundation and The Michaels Companies, Inc.

The “Trailblazer” show, with lead co-curators Patricia Hiramatsu and Ritsuko Watanabe, was overseen by a CWAJ committee to commemorate the organization’s 75th anniversary. The separate juried show of about 170 contemporary prints is also drawing many “sold” red dots as the summer progresses.

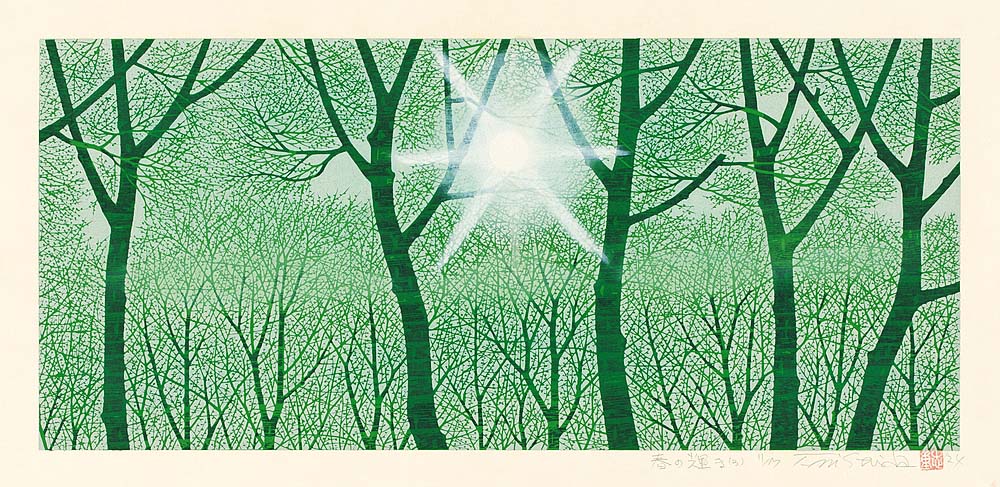

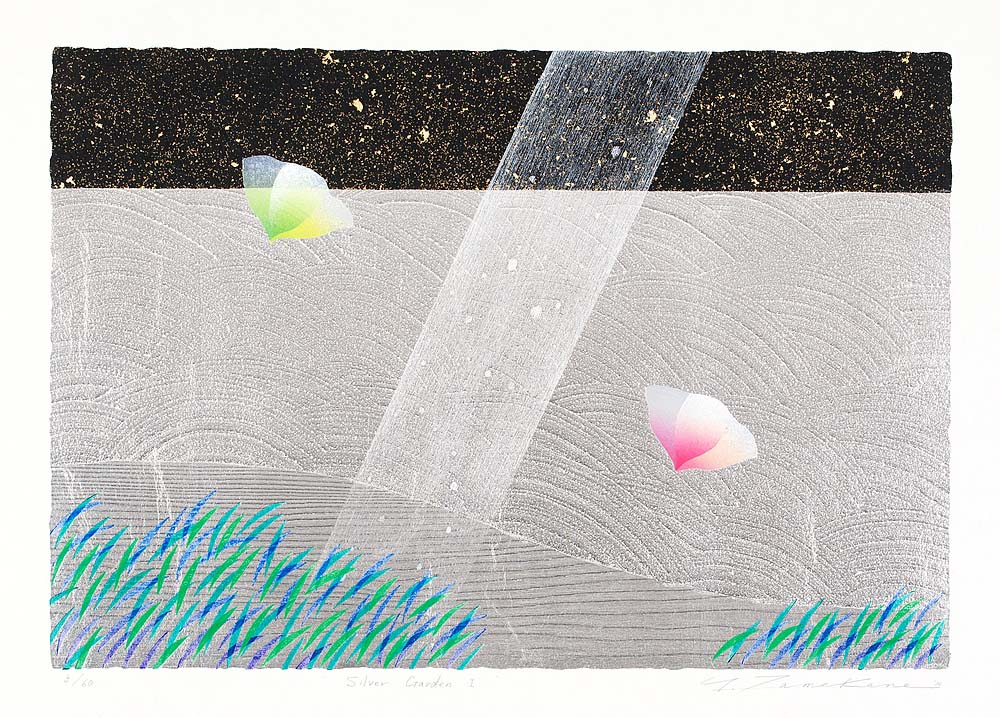

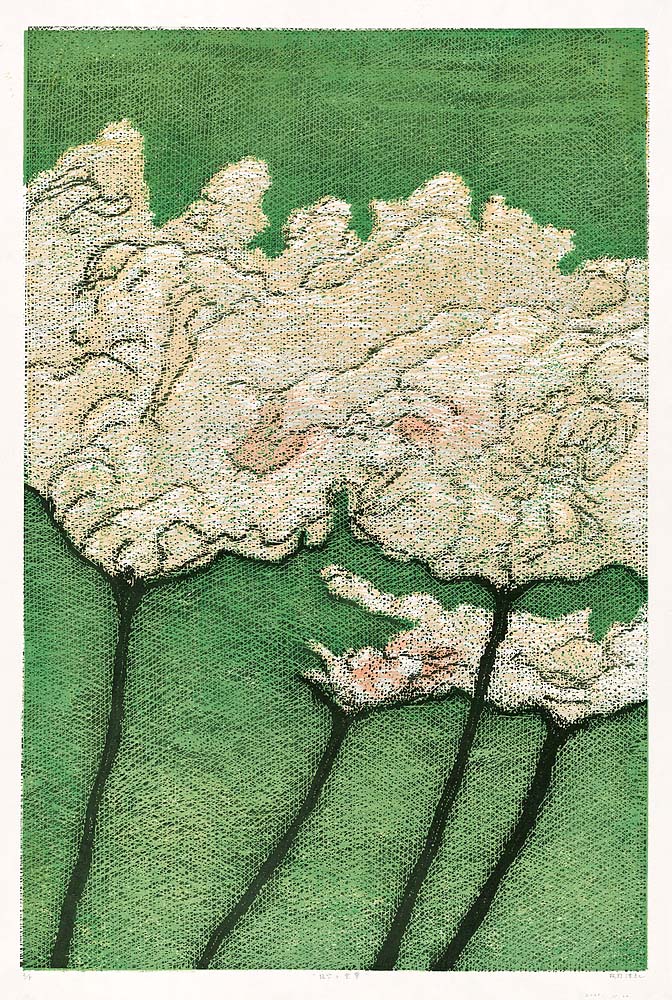

If you visit the lovely Highfield Hall, with its Stick-style Victorian, this summer or early fall you’ll encounter works that move from traditional woodblock and intaglio to lithography, etching, aquatint, silkscreen and contemporary digital innovations.

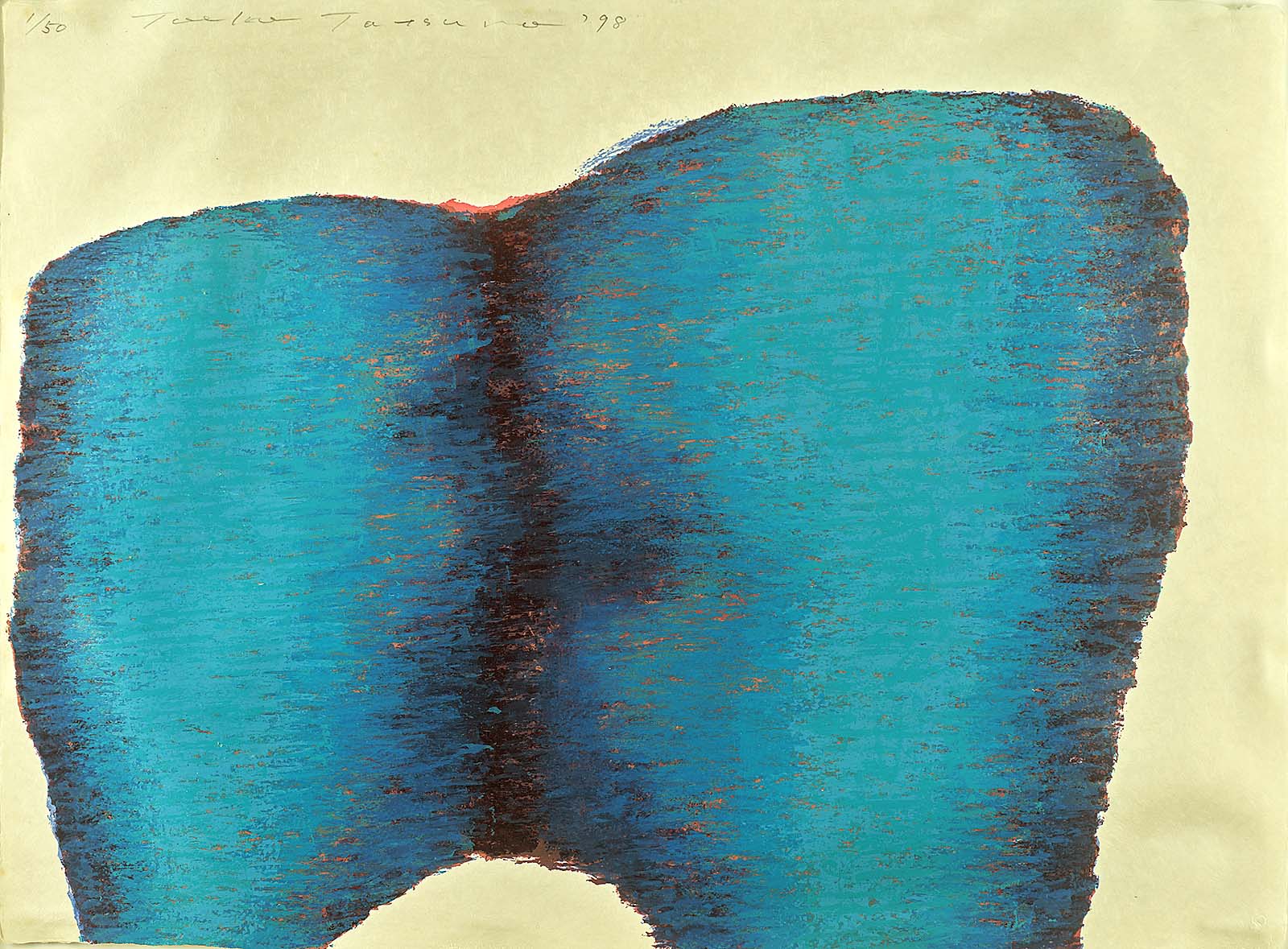

“September 28-98” by Toeko Tatsuno, 1998, silkscreen, number 1/50.

“After pandemic-related interruptions, we are thrilled to welcome back this exceptional program in partnership with the Tokyo-based CWAJ,” said Lisa Walker, co-executive director and chief development officer. This is a third collaboration between Highfield Hall and the CWAJ, and proceeds from the sale of works will go toward the association’s scholarship fund and Highfield Hall’s educational programs.

Joanne Fallon, co-chair of the CWAJ’s USA Traveling Print Show, and her counterpart in Tokyo, Naoko Yagura, have played significant roles in this year’s effort, while Joanne Dolan Ingersoll, Highfield Hall’s director, oversaw the installation. Housing the show in what was the Beebe family of Boston’s summer residence seems a perfect fit, as the home was completed at the time when the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia set off a craze, particularly in Boston, for all things Japanese.

CWAJ’s history stems from a later and darker time, when Japan was reeling from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While Imperial Japan’s declaration of surrender on August 15, 1945, brought an end to World War II, the country was on the cusp of a social revolution that would challenge traditional gender roles. Heidi Zukoski Sweetman, CWJA’s president, reflected upon the organization’s history in a 2024 article published in Japan Times: “Although there was an opportunity for women to be educated, there were more barriers and stigma to having higher education and being a working woman. Women had inferior jobs, part-time jobs and low-wage jobs with no job security. Even into the 1980s, women were expected to quit after getting married,” she said.

“Floral Clouds in a Green Sky” by Hiroki Makino, 2023, woodcut, edition of 5.

Yet within four months of Imperial Japan’s surrender, the country’s General Election Law was amended to include women’s suffrage; by 1947 the Constitution of Japan institutionalized democratic reforms, guaranteeing equal rights for men and women. While the country was still under US Occupation, Ethel B. Weed, a lieutenant working for US General Douglas MacArthur at the Allied Occupation Headquarters in Tokyo’s Chiyoda Ward, was instructed to assemble a brain trust of Japanese women who had progressive ideals. They became founding members of the CWAJ.

Today, CWAJ estimates that it costs about $24,000 to partially fund a Japanese woman’s graduate studies abroad and about $14,000 within Japan. Since 1949, when it was established, the CWAJ has awarded scholarships to over 875 women from 43 countries and awarded just over $6.8 million in grants. The annual CWAJ Print Show, established to introduce Japanese artists to international audiences, remains a key fundraising tool.

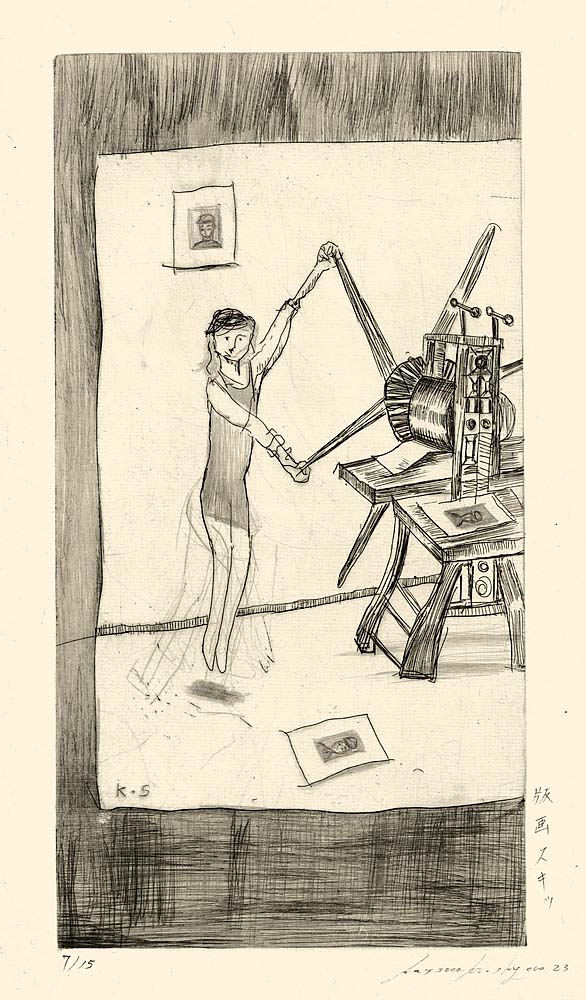

Allison Tolman of the prestigious Tolman Collection, the world’s largest publisher of contemporary Japanese print editions, delivered the show’s opening lecture to an enthusiastic audience on July 9. She offered an overview of printmaking and then segued into her relationships with some of the illustrious trailblazers. The Collection was founded in 1972 by her father (Norman Tolman) and currently has operations in Tokyo and New York.

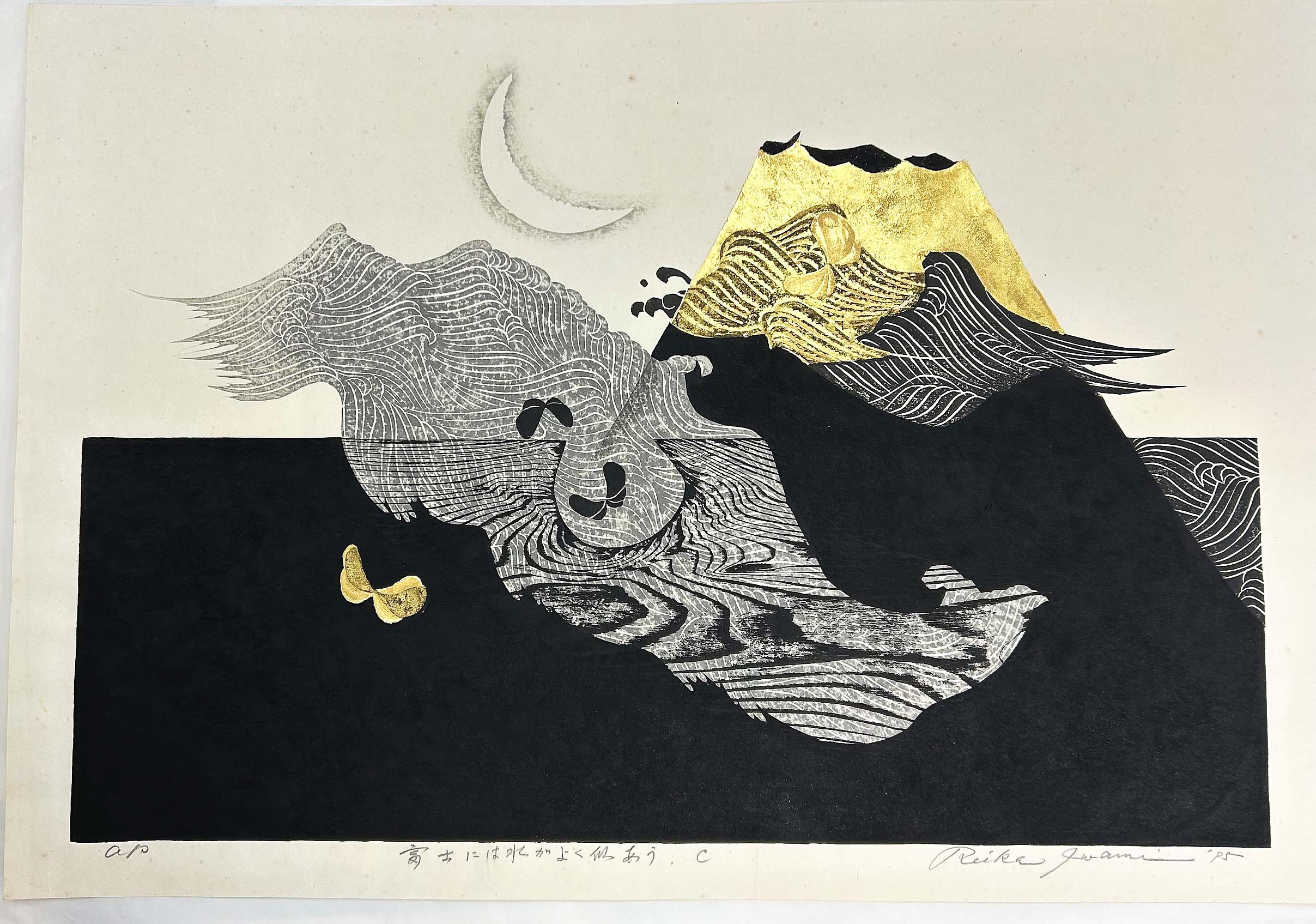

“Water Goes Well with Fuji” by Reika Iwami, 1995, artist’s proof, woodcut.

Remembering her father, who died last winter, she wrote: “it was Norman’s passion for Japanese contemporary art, his admiration and fondness for its creators and his unwavering belief that the work that they made was unrivaled and needed to be widely seen, that made the Tolman Collection of Tokyo the world’s largest publisher of Japanese prints. He was prouder of each and every one of the Tolman Collection’s artists’ accomplishments than they were themselves and thrilled to be a mentor and friend to so many of them,” she said.

It was the availability and sale of ukiyo-e prints in the late Nineteenth Century in Europe and the United States that turned the art form into a thriving industry. Ukiyo-e, which translates to “pictures of the floating world” included prints that depicted landscapes, beauties and theatrical celebrities. These prints not only inspired modernists, they also became coveted by the well-heeled middle class.

“At the start of the Twentieth Century, a new generation of Japanese printmakers came to the fore, often combining traditional techniques with individuality and freedom of expression,” Joanne Dolan Ingersoll, director of exhibitions and interpretation added. Known as sōsaku hanga (creative print) “these are generally single works — and the CWAJ Print Show is a wonderful opportunity to see the best of the best.”

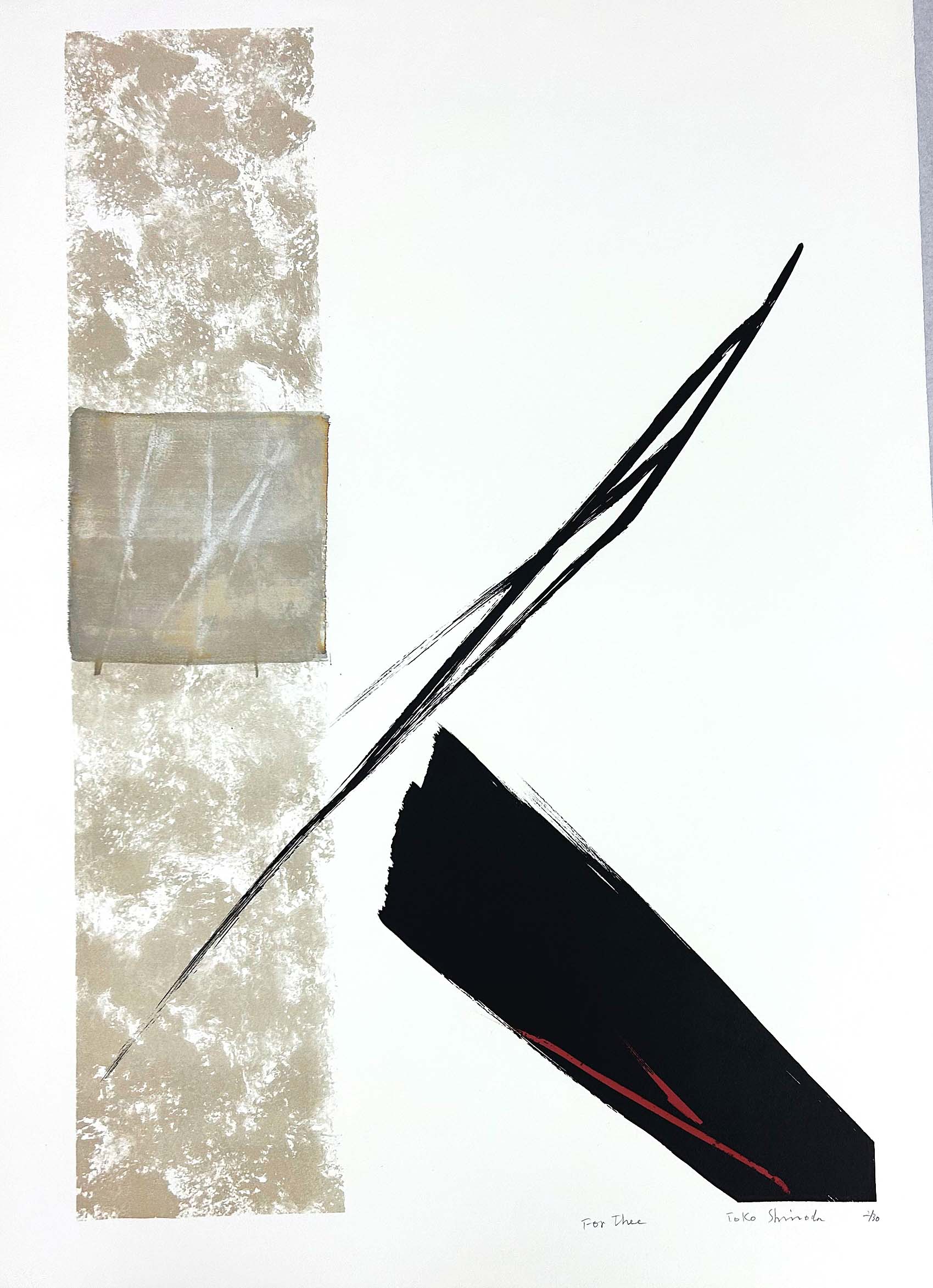

“For Thee” by Toko Shinoda, n.d., lithograph, number 2/30.

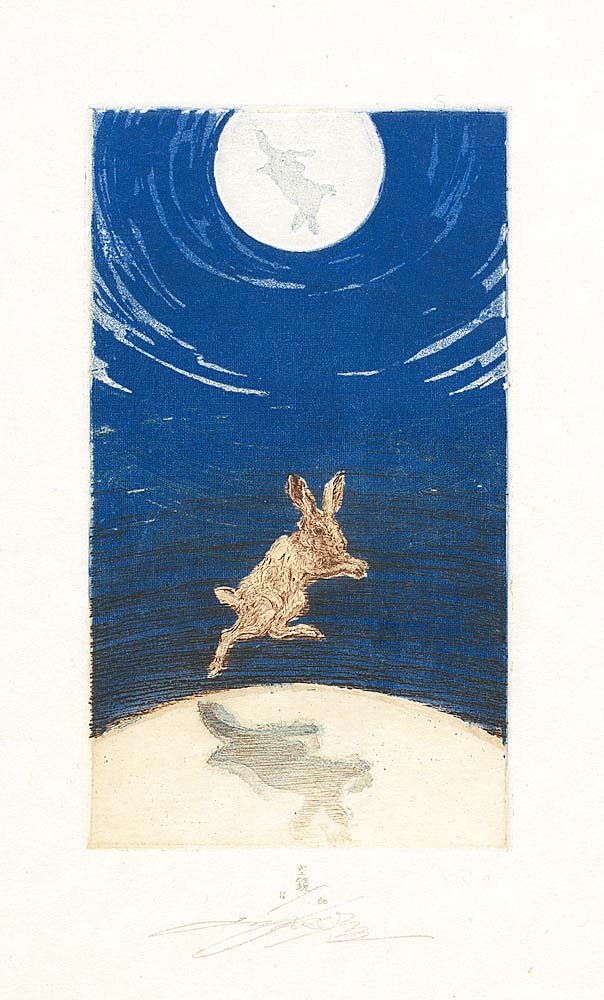

Three of Tolman’s favorite printmakers in the “Trailblazers” exhibition are Shinoda Toko (1913-2021), best known for works that merged traditional calligraphy and poetry with abstraction; Yoshia Chizuko (1924-2017), a leading figure in Japan’s feminist art movement, who became known for her experiments with scale, surface texture and optical illusion; and Iwami Reika (1927-2020), whose art sought to capture the essence of nature in works that combined ink, metal leaf, mica and handmade paper. The two other women of note are Tatsuno Toeko (1950-2024), a leading modernist printmaker, whose layered prints often combine multiple techniques and are distinct for their abstracted shapes and rich palette; and Noriko Yanagisawa (b 1940) whose work incorporates wings, birds, ammolites and half-human/half-beast figures as motifs. In recent years, Yanagisawa’s subjects have turned to the animals of Fukushima left behind by the Great East Japan Earthquake; victims of fallout from Chernobyl; and the plight of people and animals suffering in war-torn Ukraine.

Looking back over her family’s history, Tolman recalled, Iwana Reika “was among the very first artists the Tolman Collection represented and, from the start, she stood apart through the sheer power of her work. Her background in haiku — she wrote one daily — seems present in much of her work. She believed that the discipline of verse taught her the art of ‘eliminating what is not necessary’ in her art and you can feel that in every one of her prints,” she said. Reika helped found the Women’s Print Association (Joryu Hanga Kai), in 1956, “an act of quiet defiance in a world that often left women artists sidelined. But she never seemed to push. She simply made extraordinary work and let it speak for her. She exhibited regularly in major art biennales and international shows.”

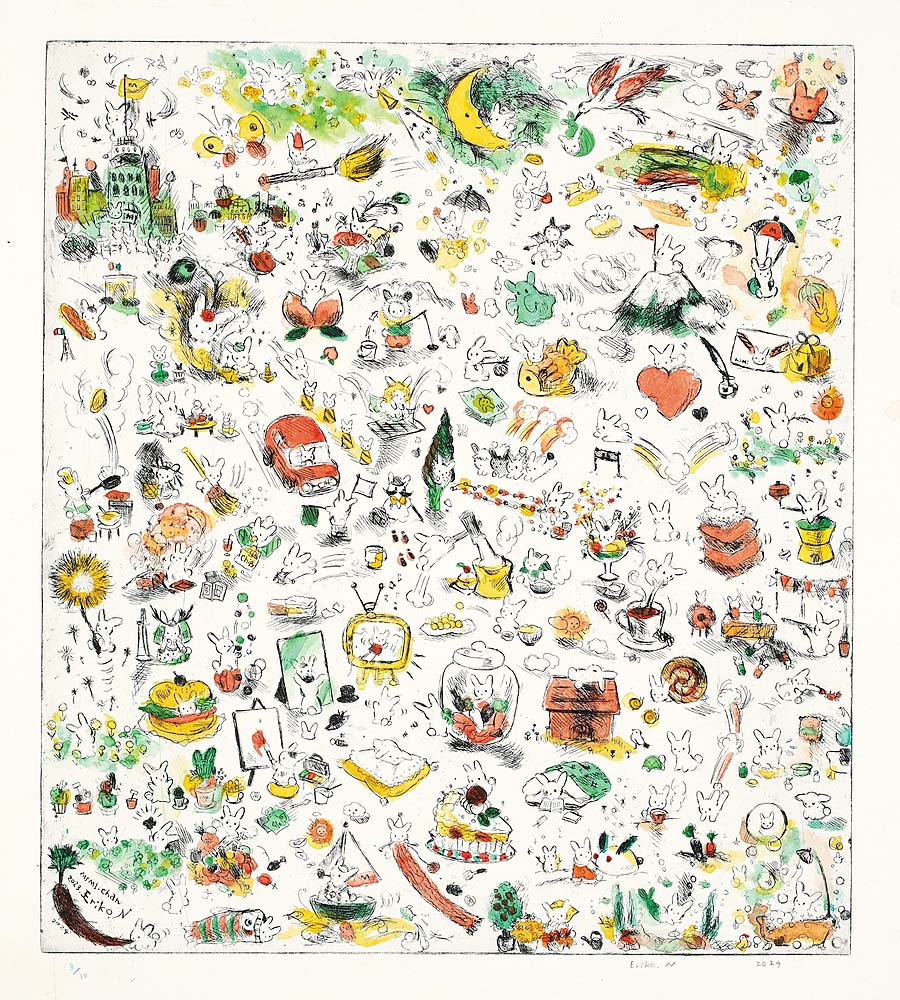

“MIMI-chan” by Eriko Notsu, 2024, etching, hand coloring, transparent watercolor, edition of 10.

Another legendary pioneer is Toko Shinoda, who was born in 1913 and initially studied calligraphy. She later rebelled against the exactness of the art, preferring to transform her calligraphic strokes into paintings and prints, Tolman said. During the first of three visits to New York in the late 1950s and 1960s, Shinoda acquired a loyal following. She exhibited with Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollack. A painter as well as a printmaker, Shinoda attained international renown at mid-century and remained sought after by major museums and galleries worldwide for more than five decades.

Chizuko (1924-2017) co-founded The Women’s Printmaker’s Association in 1956, and became known for prints that experimented with scale, surface texture, optical illusion and collage. A major retrospective of her work, which situates her art within the context of international modernist art and Twentieth Century printmaking, is scheduled for the fall at the Portland (Ore.) Art Museum.

How Highfield originally came to host this juried show remains a bit of a mystery; although the home’s original owners, the Beebe family, were Boston Brahmins who were known to have traveled to both Europe and Japan during the Gilded Age. It was during this time that upper class Bostonians, from Isabella Stewart Gardener to Dr William Sturgis Bigelow, were bitten by the Japanese art bug — Bigelow would acquire some 40,000 pieces which ultimately were donated to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

By 1994, Highfield Hall had fallen into major disrepair and a citizens’ group rose up to save it from the wrecker’s ball. By April of 2007, the home had been fully restored and opened for its first full year of operations. Today, it operates as a non-profit foundation, and a thriving cultural center, offering concerts, festivals, international art exhibitions, culinary classes, family programs and educational opportunities. For those of us visiting or living year-round on Cape Cod, it’s a treasure.

“Trailblazers: Celebrating Contemporary Japanese Prints” is on view through October 26.

Highfield Hall & Gardens is at 56 Highfield Drive. For information, 508-495-1878 or www.highfieldhall.org.