Vermont collectors Jason and Dana Routhier, here with their son, Felix, gravitate to mid-Twentieth Century master works on paper. The Routhier Collection. Photography by Andy Duback.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SHELBURNE, VT. — Many curators will agree that one of the most difficult tasks in organizing an exhibition can be choosing its title. Not so “Hard-Edge Cool: The Routhier Collection of Mid-Century Prints,” on view at Shelburne Museum November 19–January 22.

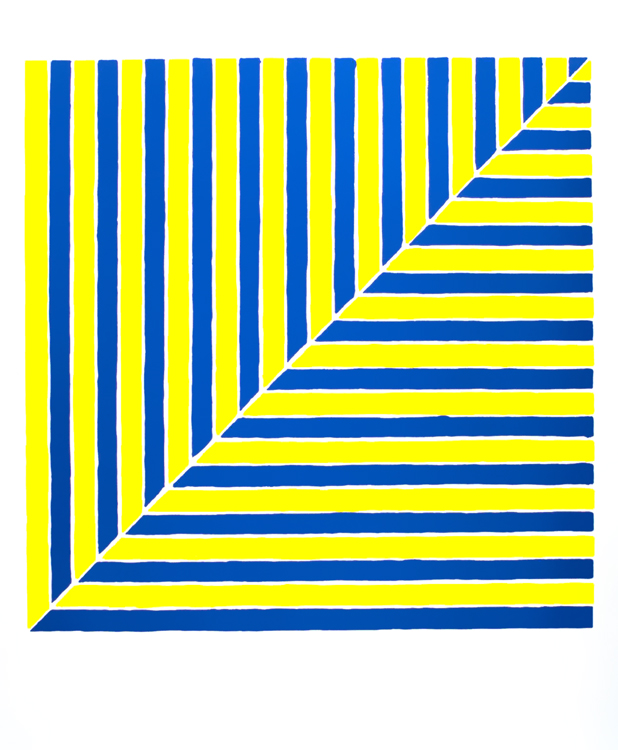

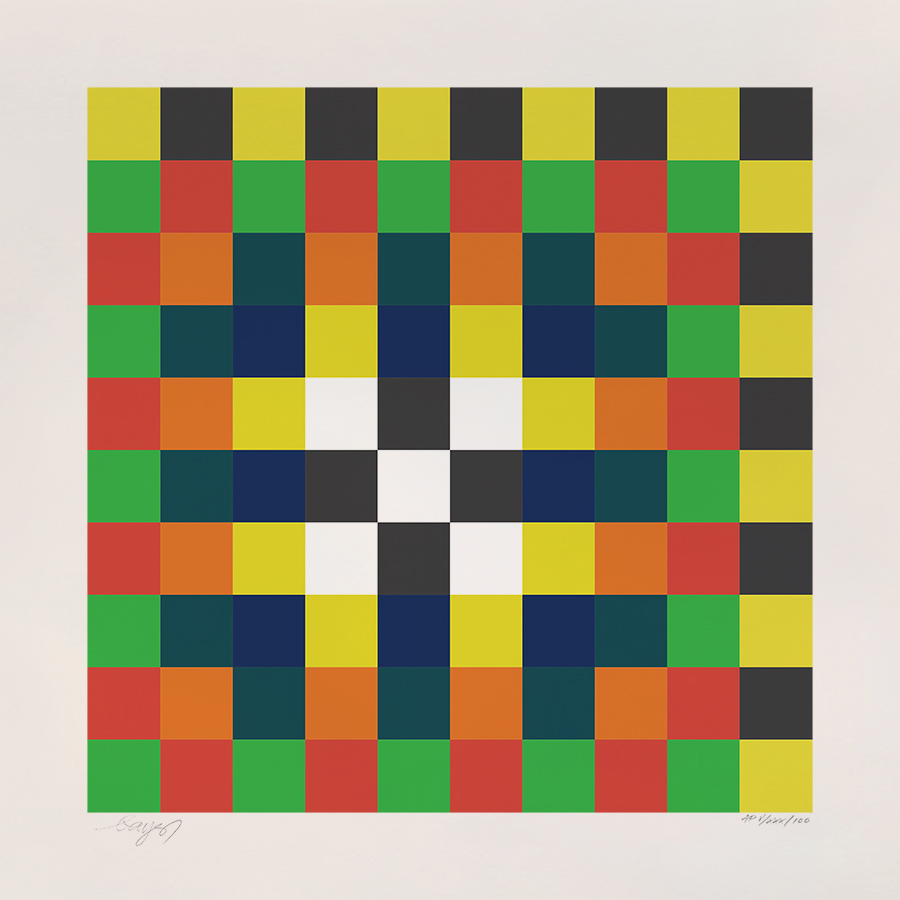

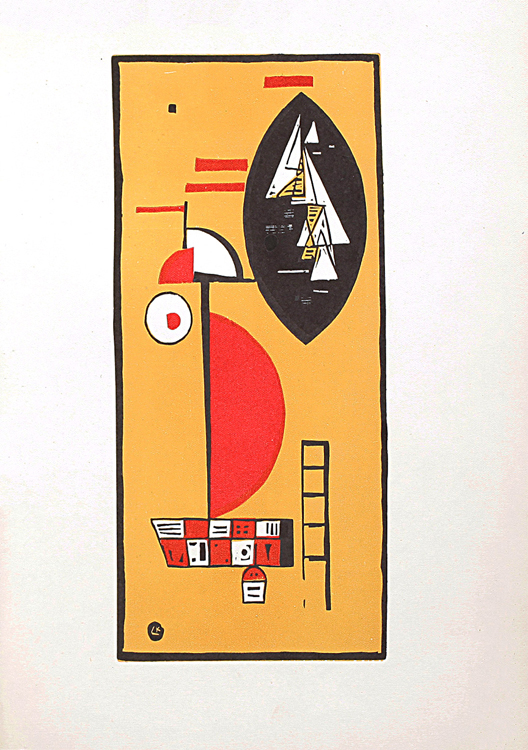

It was the first title Carolyn Bauer, assistant curator at the Shelburne Museum, came up with and Jason Routhier just loved it. “I think it hit really perfectly on what the exhibition is,” marveled the collector, who assembled works on paper by Josef Albers, Jean Arp, Max Bill, Wassily Kandinsky, Ellsworth Kelly, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Frank Stella and other masters with his wife, Dana.

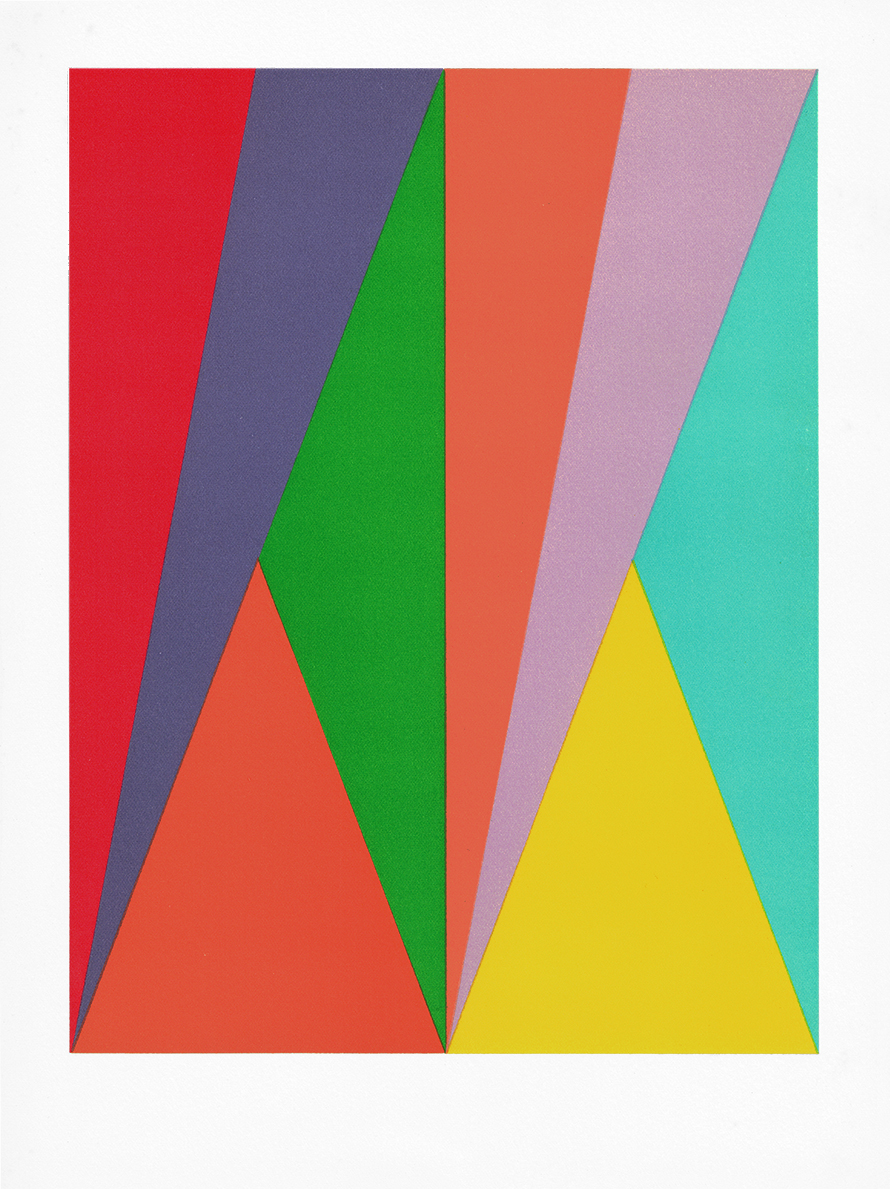

“Cool” does seem an apt descriptor for the works on view, all hand-printed expressions of a precise, highly graphic style more often associated with painting in the 1950s and 1960s. This was the time when a countercultural concept of “cool” was emerging in America and Europe. Some of the artists represented here were active participants in that counterculture. Accordingly, much of the work reads as rebellious, graphic and unapologetic, yet detached in a way that corresponds to and defines the word “cool.”

As part of this discussion about names and words, it bears noting that while the author of this article shares a surname with the collectors, they have no known family relationship. As a further disclaimer, none makes a special claim to coolness.

Hard-edge, or geometric, abstraction is defined by broad, clearly defined areas of uniform color. In hard-edge painting, brushstrokes are invisible and the paint surface is perfectly flat. In prints, meticulous screen-printing processes, more often than not, provide the same kind of immaculate, dimensionless precision. With few exceptions — Ellsworth Kelly being the main outlier — the work is fully abstract, representing nothing in the known world. For Jason Routhier, who is a graphic designer, geometric abstraction represents “where design started and where I wish it still would be.”

Where geometric hard-edge abstraction itself started is another question. In part, it was a reaction to Abstract Expressionist, or “Action” painting, which dominated the New York art world in the postwar years with its energetic, abandoned and very visible slashes of paint. Artists like Kelly, Albers and Stella were carving out an alternative direction for art while also clearly looking back at the abstract work of interwar artists like Arp and Kandinsky, who arrived at pure abstraction a generation before the Abstract Expressionists. Often, it is worth noting, they experimented with printmaking.

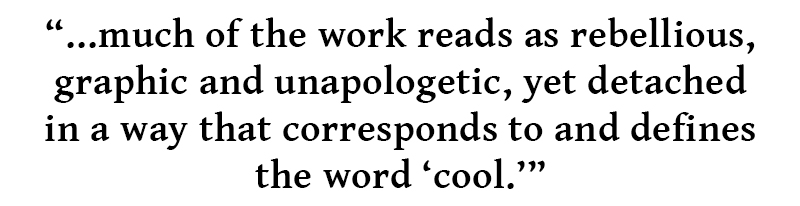

Bauer points out that these artists, in America and in Europe, were also very interested in so-called “primitive” and vernacular art, which is where it dovetails with Shelburne Museum’s own collections. It is not difficult to see, for example, similarities between a Log Cabin quilt of the 1870s and Stella’s 1964 print of interlocking blue and yellow lines.

“Of course,” the curator qualified in a recent conversation, “the folk artists were trying to assimilate real life, and geometric abstractionists are really just looking at formal concerns.” Still, in printmaking there is a very real sense of craft, manifested in the materials — the richness and texture of the inks, the deckled edges of the paper — as well as in the very physical, even workmanlike, process of pulling a print. There is an irony implicit in expressing such a transcendently visual artistic ideal with this resolutely palpable art form. Bauer agrees: “This idea of getting away from the artist’s hand, making it look like it was machine-made — that dichotomy is beautiful.”

The show, Bauer says, “is a great opportunity, not only for sharing geometric abstraction with our public, but also the art of collecting … both topics really resonated with the curatorial staff.” She points out that Shelburne Museum itself was founded by a highly motivated and visionary collector, Electra Havemeyer Webb, who conducted many of her collecting activities from her home in Vermont. Similarly, she says, “It’s a fun story to look at how Jason and Dana Routhier, living here in Vermont, have been able to amass such a beautiful collection. It’s a story worth telling and may inspire future collectors.”

In fact, that is exactly what Shelburne Museum did for Jason Routhier, who grew up in the area and was a frequent visitor on school field trips. “I have always loved that museum,” he enthused recently, noting the museum’s reconstructed Nineteenth Century printing shop as a particular point of connection with his current interests. The Shelburne Museum of his youth would not have provided much of a context for geometric abstraction. It is only relatively recently, under director Thomas Denenberg and his young curatorial staff, that the museum has made a major commitment to later Twentieth Century and contemporary art. Jason Routhier developed an interest in hard-edge art more or less on his own while still a high school student in the 1990s. Living in a place where exhibitions of such works were, at best, few and far between, he found them in art books and exhibition catalogs.

Jason did not begin to collect in earnest until years later. In fact, it was Dana who acquired the first major work in their collection. Around 2009 or 2010, she gave Jason the portfolio New Shapes of Color, produced by Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum in 1966. Printed as a companion to the exhibition of the same name, it included four screen prints, with one by Ellsworth Kelly, already a longstanding favorite of Jason’s.

Thanks to the digital revolution, the hard-edge works that were so elusive for Jason as a teenager are now just a few clicks away online, where he conducts most of his collecting activities. He has developed what he calls a “network of referrals,” connections and transactions that lead to further opportunities. “I kind of lucked out because I got into this stuff before it got really popular,” he says, while acknowledging that there are still bargains to be had for those who know what they are looking for. “Sometimes when you are really obsessed with this work, things pop up and people can’t see their signature — and you just know.”

Still, “it’s always been about finding the pieces we love,” he says. That “we” is reflected in the exhibition itself. Shortly before their 3-year-old son, Felix, was born, Dana surprised Jason with the birthday gift of tickets to travel to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art in Wisconsin to see the Ellsworth Kelly retrospective. As the couple walked through the adjacent exhibition of work by Kelly’s contemporaries, Dana remarked, “All this stuff is so familiar.” The couple realized they already owned examples by many of the featured artists.

It was at this point, Jason remembers, that Dana really took on the role of the collection’s manager. “She started a database and began organizing stuff — taking things out of tubes, taking care of it and archiving it,” he says. Dana even reached out to the Shelburne Museum. To the couple’s surprise, the institution was interested in displaying their collection. The exhibition began taking shape right around the time the museum hired Bauer, for whom the couple has high praise. Right from the beginning, Jason says, “It was great to see how young and vibrant that whole staff was.” Some might even say cool.

The work can be challenging. The artist Nicole Eisenman, for instance, recently ranted to The New York Times that formalism in general, and the art of Ellsworth Kelly in particular, is “too divorced from reality” and “too privileged.” But Bauer points out that while pure abstraction can seem baffling or even exclusionary to some, its language of pure color and form is in fact universal, based on the human capacity for sight. Excepting those with visual impairments, that capacity is shared across time and cultures in a way that more representational themes generally are not.

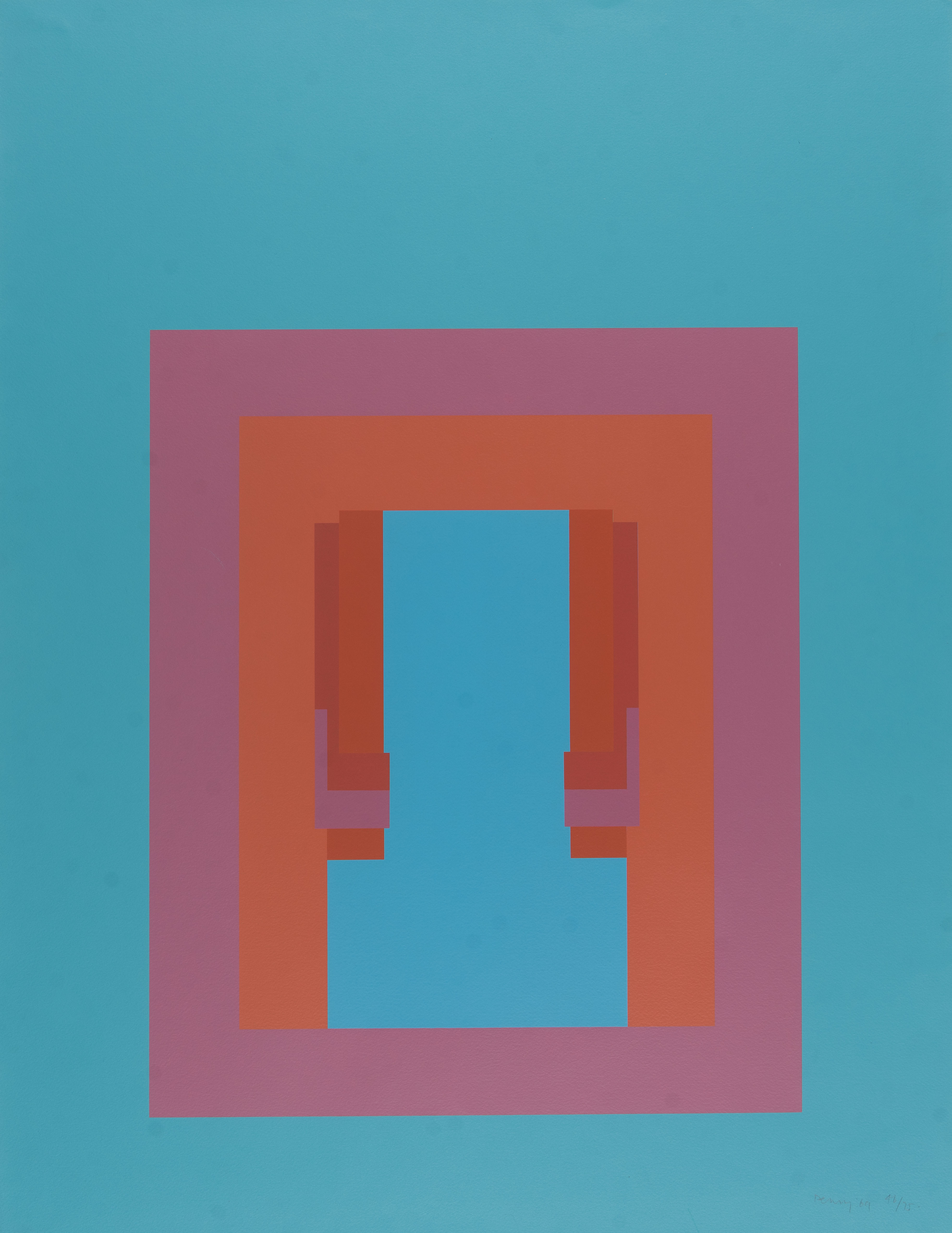

Bauer also discussed how, in moving away from Abstract Expressionism, in which artistic personalities loomed large, “here with geometric abstraction … you don’t have to see the artist’s hand, you don’t have to know the artist’s biography” in order to understand or engage with the work. Illustrating this point is one of the video projections that Bauer has incorporated into the installation. Along with several showing Josef Albers teaching and at work in his studio — the circle of students and collaborators who coalesced around him at the Bauhaus, Yale and Black Mountain College of the Arts is a major theme throughout the show — there is also CBS footage of the opening reception of “The Responsive Eye,” an Op Art exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1965.

“It is looking at the museumgoers of the time,” Bauer observes, “the balance of people saying they’re loving it because it’s engaging them visually, as well as people who are cringing because they’re saying ‘what is this art?’” Jason adds, “Vermont is a really interesting place to put this up. I think we could get a really pure reaction that could be a lot like the reaction when these things came up in galleries originally. I really hope that somebody’s mind is a little bit blown.”

There are many other delights in “Hard-Edge Cool.” Bauer has recreated the back wall of Café Aubette in Strasbourg, France, a public space designed by Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Theo van Doesburg that uses the idiom of geometric abstraction to convey the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk — a total work of art, in every surface and detail. The exhibition also reflects the Routhiers’ particular interest in women practitioners of hard-edge abstraction, whose contributions have often been underappreciated.

It may not be peak season for visitors to Vermont, but this show may supply reason enough for a wintertime visit — it should be pretty cool. The Shelburne Museum is at 6000 Shelburne Road. For information, www.shelburnemuseum.org or 802-985-3346.