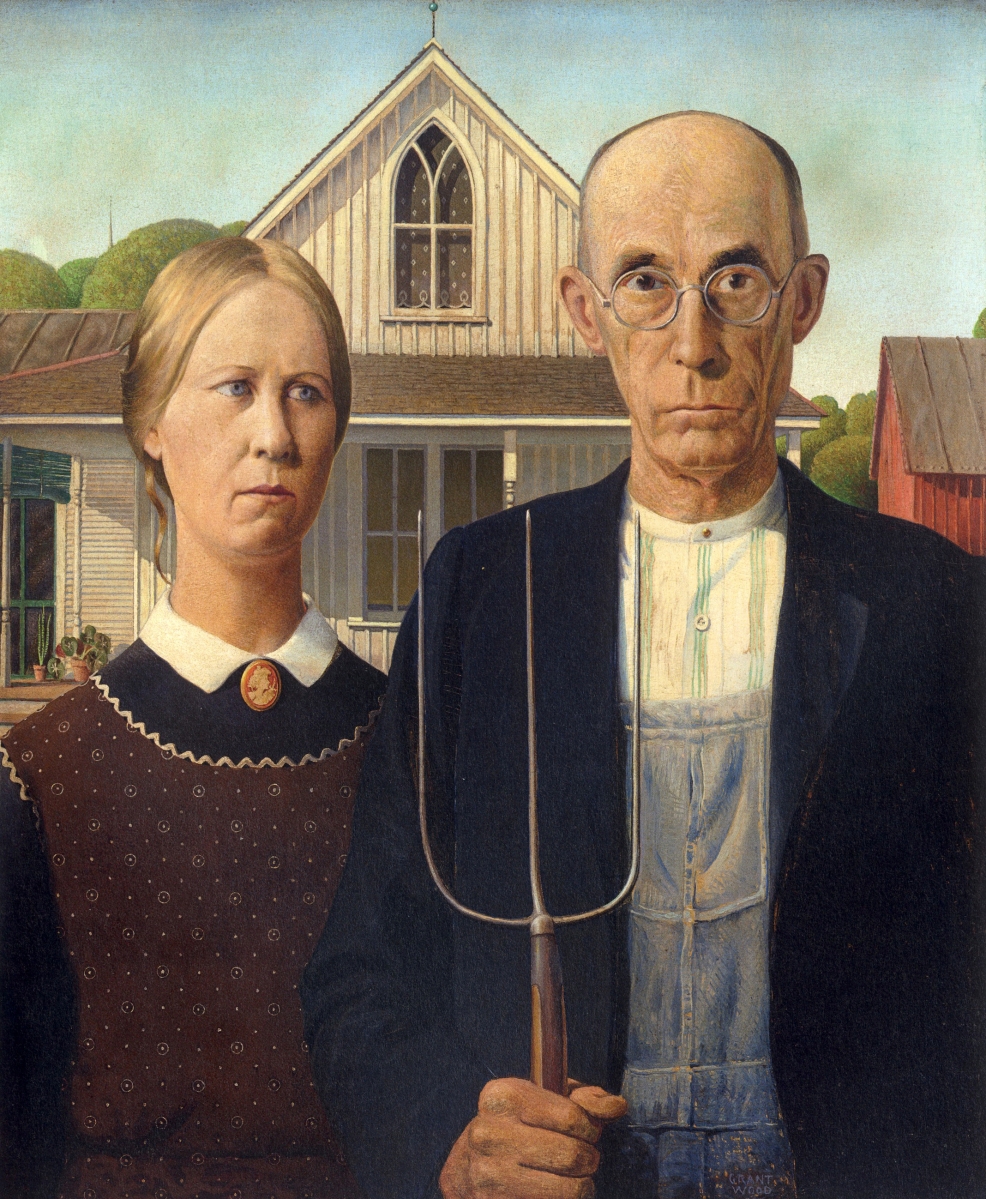

“American Gothic,” 1930. Oil on composition board, 30¾ by 25¾ inches. Art Institute of Chicago; Friends of American Art Collection. Photo courtesy Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY. All works are by Grant Wood. ©Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY – Grant Wood has always been a cipher. From the moment he burst onto the mainstream American art scene, his perplexing paintings -1930’s “American Gothic” being the defining example – have always seemed to require decoding. In an era when painters were increasingly approaching their work as exercises in pure color and form, Wood remained resolutely representational, grounded in the visible world, in ways that seemed outdated to some and intriguingly enigmatic to others. The mythic complexity of Wood’s work is the subject of “Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables” at the Whitney Museum of American Art March 2-June 10.

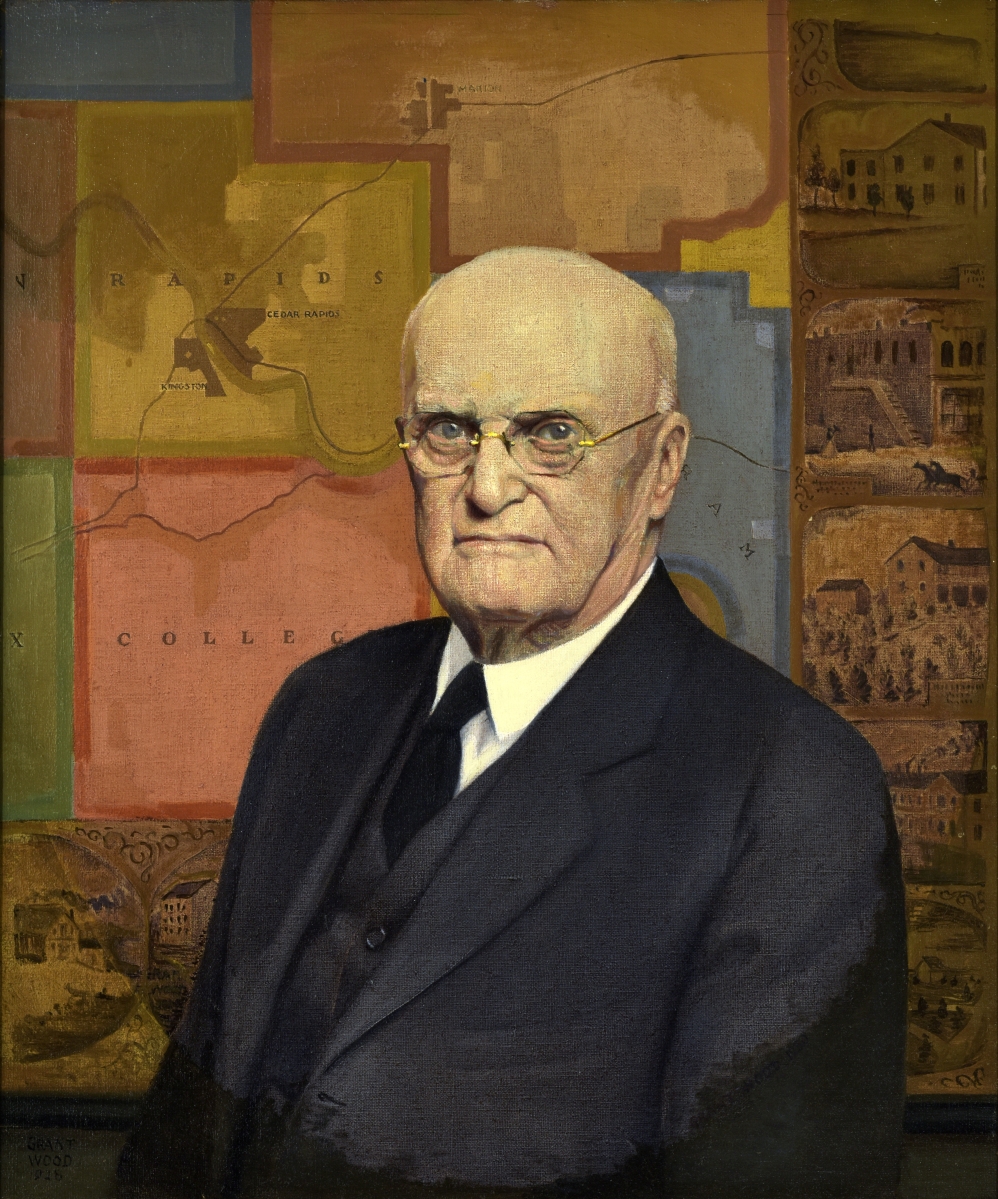

Wood, not without some justification, always felt himself to be an outsider to the American art scene. He never studied or lived in New York, which dominated artistic production and criticism at the time. In fact, he resisted suggestions that he should do so to be taken seriously. His background was in decorative crafts and portraiture, considered inferior genres by many Modernists, and his home base remained his native Cedar Rapids, Iowa, throughout his life.

Nevertheless, compared to other Regionalist artists – and even many hundreds of struggling and now-forgotten New York Modernists – he became the quintessential insider, winning a spot in the Whitney Biennial, a coveted professional membership in the National Academy of Design, a solo show in New York, important federal commissions and a place in Art History 101 books for all time.

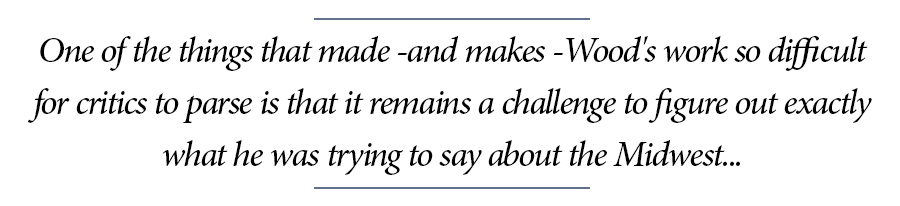

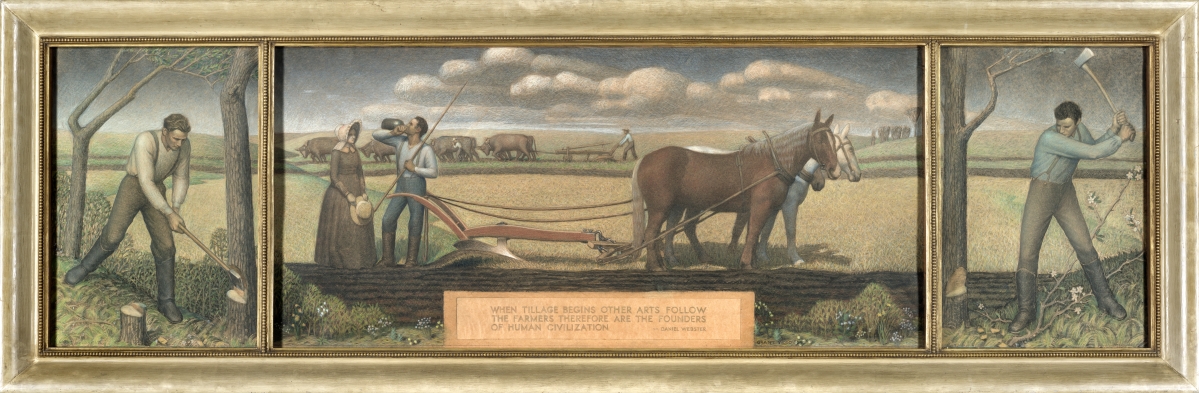

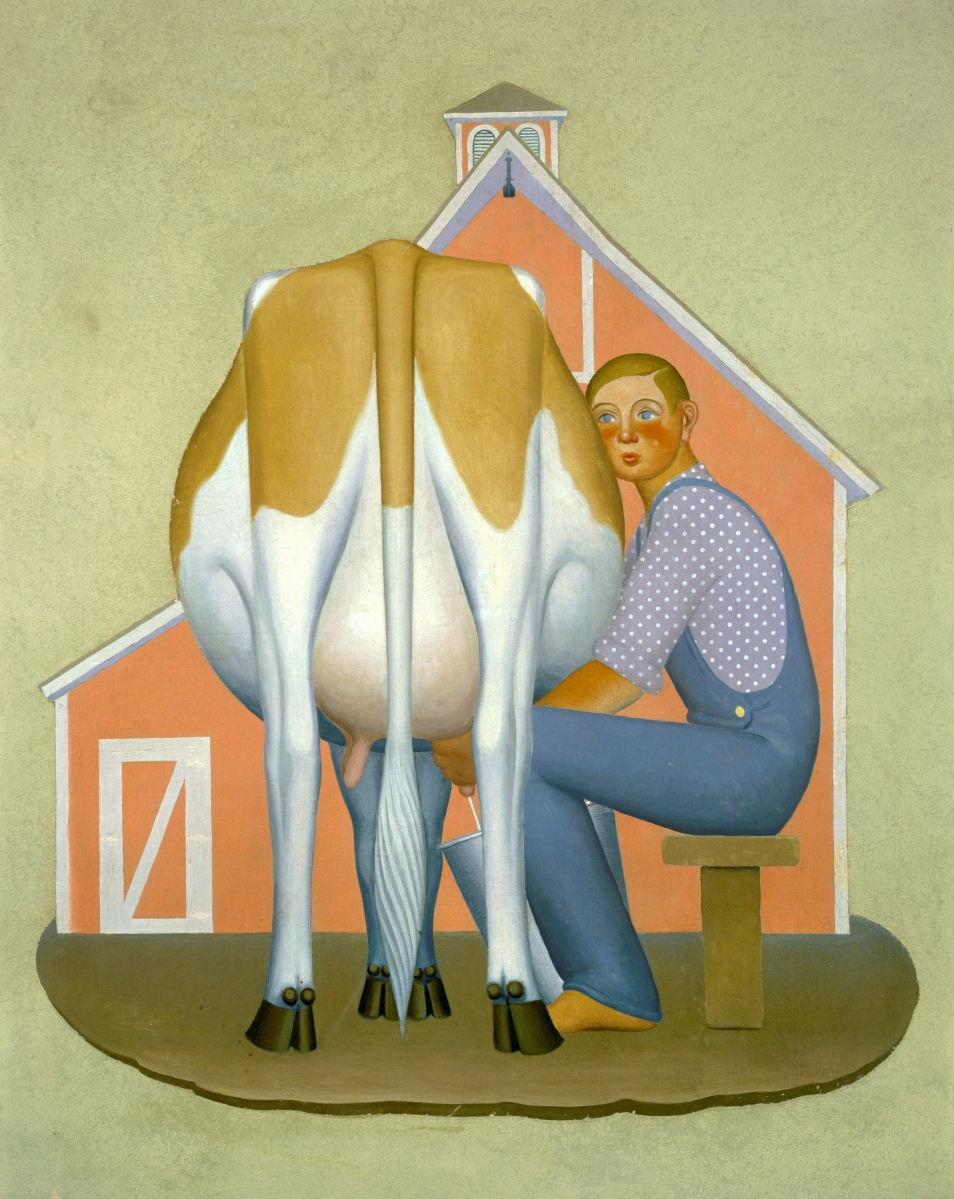

One of the things that made -and makes -Wood’s work so difficult for critics to parse is that it remains a challenge to figure out exactly what he was trying to say about the Midwest. His early works – paintings and decorative arts – seem resolutely celebratory: portraits of apple-cheeked toddlers, public murals celebrating home and harvest and whimsical assemblage-like sculptures that blend bits of farm machinery with reassuring prairie imagery.

An introductory gallery in the exhibition, painted eggplant purple for a sense of domestic intimacy, features many of Wood’s early decorative pieces, including an irresistible chandelier made for the so-called Iowa Corn Room in a Cedar Rapids Hotel. “I predict the corncob chandelier is going to be the star of the show,” says the Whitney’s Barbara Haskell, the exhibition’s curator, noting that it is fully functional and will be illuminated in the exhibition.

An introductory gallery in the exhibition, painted eggplant purple for a sense of domestic intimacy, features many of Wood’s early decorative pieces, including an irresistible chandelier made for the so-called Iowa Corn Room in a Cedar Rapids Hotel. “I predict the corncob chandelier is going to be the star of the show,” says the Whitney’s Barbara Haskell, the exhibition’s curator, noting that it is fully functional and will be illuminated in the exhibition.

Works like the corn chandelier were unknown to the major art critics of the time, of course. They were seen only locally and were often made for very specific commissions that determined their aesthetics to a high degree. It was only later, once Wood had become an ineluctable part of the American art world, that some critics and scholars saw such works as representative of unalloyed regional pride and optimism, a kind of prescriptive ideal of Americanness. Such an assessment might just as easily have been levied to praise Wood as to condemn him – there were nearly as many advocating for a home-grown “American” art in the prewar years as there were those championing European Modernism. But in any case, this was a very partial analysis of an art and an artist whose contributions were far too nuanced to simply be set as an anchor on one side of a tug-of-war over the future of American art.

“[Wood was] not a booster for the Midwest,” Haskell recently observed. “He tried to convince artists to stay in their own region… He was very critical of artists who came to the Midwest and started to paint cows and red barns – that was as dubious as artists going to Paris,” which in fact Grant himself had done, during a short-lived Impressionist phase. “He felt people had to paint what they knew,” Haskell continued. “He didn’t seek to create a national stereotype – it wasn’t until after he died, almost, when the idea [emerged] that he was somehow arguing that only the Midwest was Americanness. There were other people that imposed that stereotype on his work.”

And in fact, it is not necessary to scratch the surface very much at all to realize that Wood’s mature paintings are far from unambiguously celebratory about either the Midwest or America itself. When “American Gothic” – Wood’s memorable and much-reproduced double portrait of an elderly farmer, pitchfork in hand, and a younger woman standing in front of a peaked-gable farmhouse – garnered the artist unprecedented attention in 1930, America was at the lurching precipice of the Great Depression. Even those for whom the couple seemed to represent a kind of heartland steadfastness in the face of economic collapse – Wood himself described them as “good solid people” – could not deny a grimness and uncertainty in their expressions.

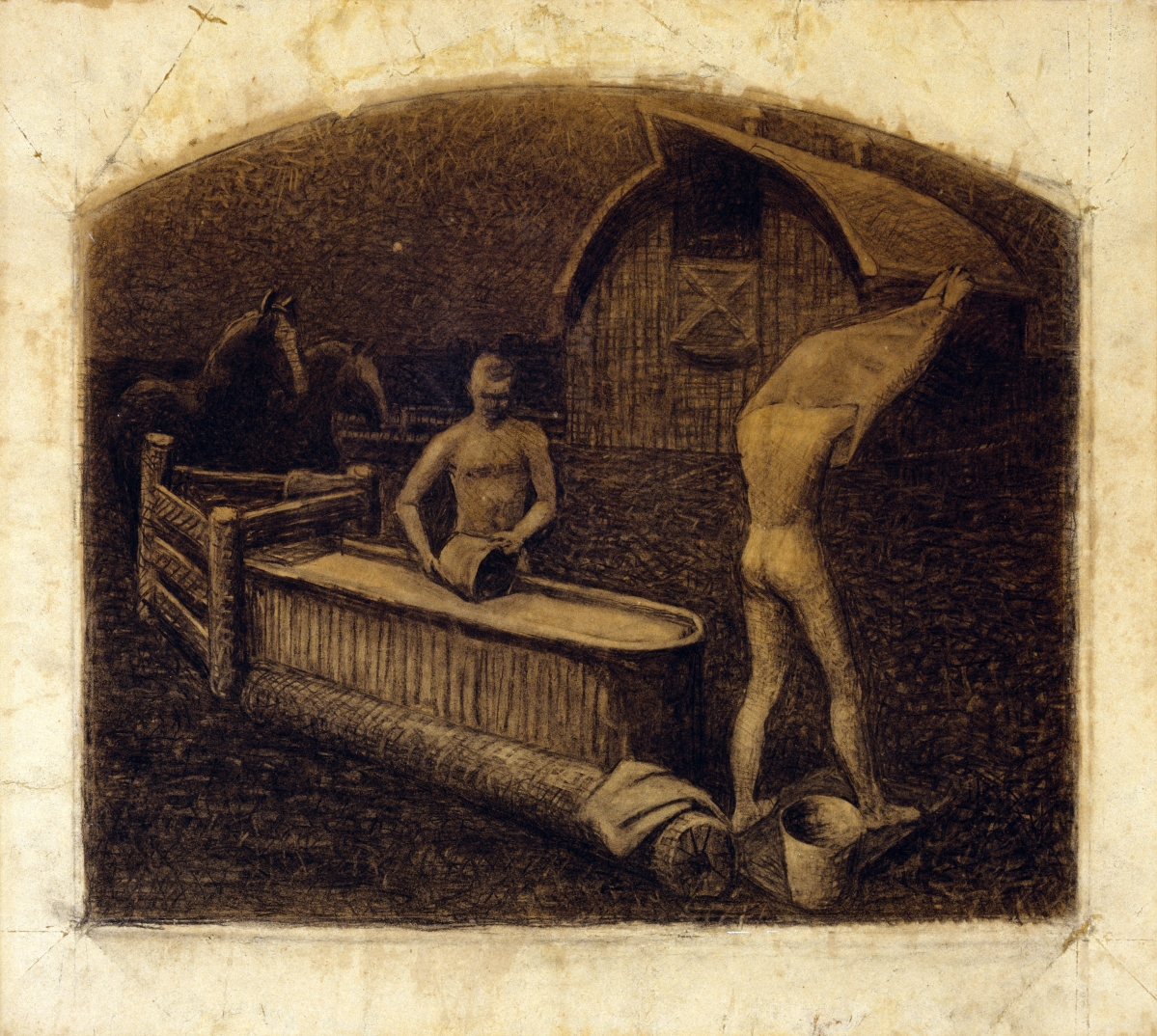

“Study for Breaking the Prairie,” 1935–39. Colored pencil, chalk and graphite pencil on paper, 22¾ by 80¼ inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, gift of Mr and Mrs George D. Stoddard.

“The painting clearly contained a story, but one so enigmatic that it defied ready explanation,” Haskell writes in her essay for the exhibition catalog. “Its very inscrutability invited boundless interpretations.”

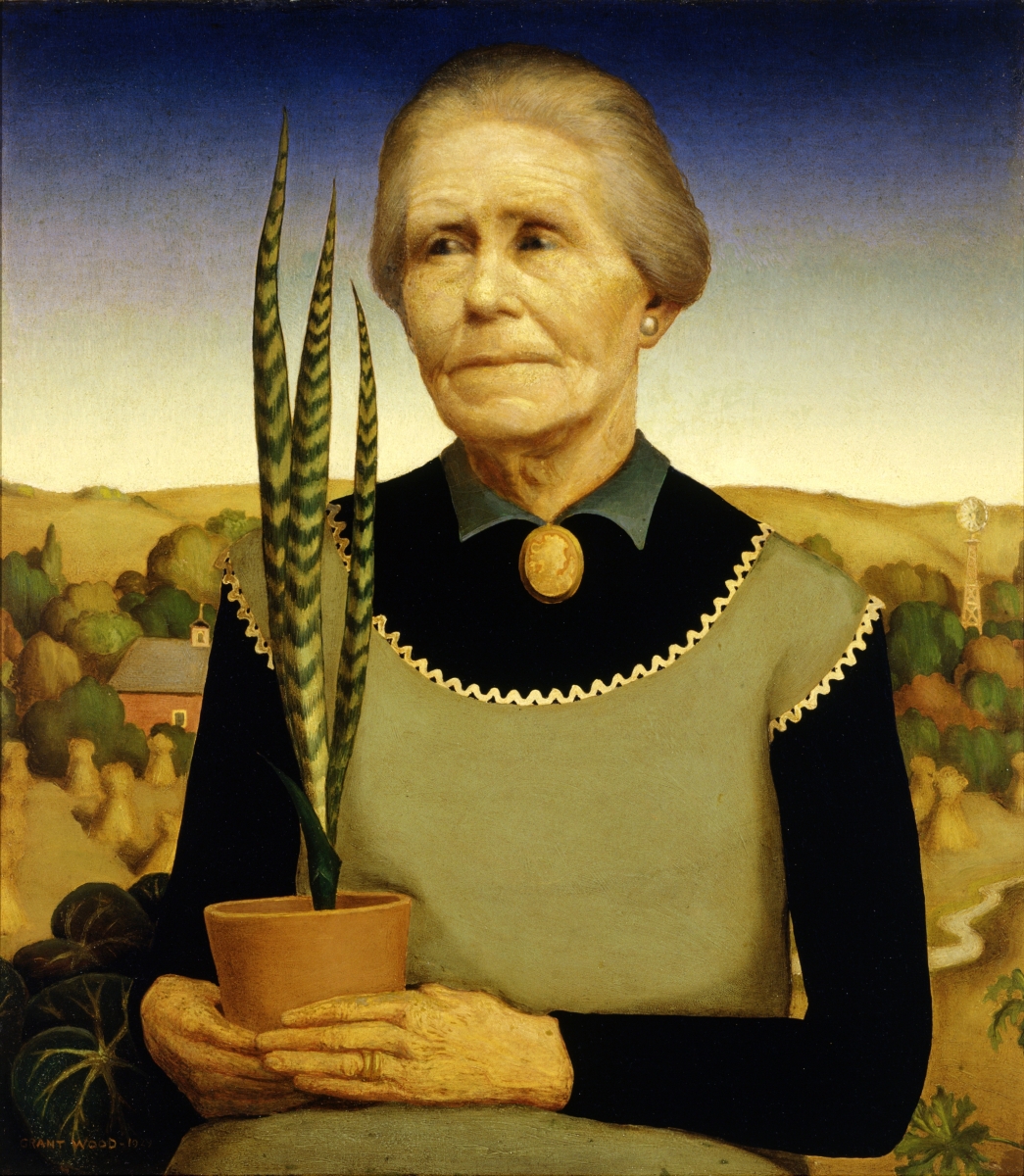

Part of the mystery of “American Gothic” is that there is a sense that it came out of nowhere – Wood was virtually unknown before it was exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago shortly after it was completed. In fact, Wood had been seriously engaged with portraiture – challenging, ambiguous portraiture – for several years. With memories of his European travels in mind, he created portraits of rural businessmen and farm wives as if they were early Flemish – Gothic, if you will – saints: bust-length portraits set before expansive, atmospheric landscapes, with tokens like maps, plants and fruits suggesting the sitters’ personal histories. “Portrait of John B. Turner,” “Woman with Plants” and “Arnold Comes of Age” are defining examples. “American Gothic,” it should be obvious from the title alone, is very much in the same vein. Like saints, his sitters – good and solid though they may be – are complicated and intense, embodying both light and dark.

While the Whitney’s exhibition takes its name from Wood’s best-known painting, its purpose is not necessarily to offer any single revisionist interpretation of it, or even to fully summarize all the various interpretations to date, a Sisyphean task, in any case. Understanding that there are nearly as many takes on “American Gothic” – and, indeed, Wood’s career as a whole – as there are historians of American art, Haskell has assembled a team of scholars to address, in the catalog, a few specific, somewhat underrecognized veins of influence in Wood’s work. Each essay addresses the artist’s wider oeuvre, but each takes care to address “American Gothic” in turn.

For example: Glenn Adamson, who deals with Wood’s roots in craft, notes the female figure’s rickrack apron and cameo brooch, along with the architecture, as evidence of Wood’s interest in design. Shirley Reece-Hughes, who discusses Wood’s involvement in theater, points out how the painting mimics the static poses of tableaux vivants. Eric Banks, who explores Wood’s participation in the thriving Iowa literary scene, finds a kinship between Wood’s dour figures and the characters of Sinclair Lewis and others. Emily Braun, who uses the literary and artistic genre of “Magical Realism” as a framework, unpacks the repressed sexuality of the picture, with its “intimations of incest” and “creepily” symbolic potted plants (the same “mother-in-law’s tongue” that appears in “Woman with Plants”). And Richard Meyer, in his wittily titled “Grant Wood Goes Gay,” observes how critical reception to “American Gothic” used coded language to call into question the artist’s own sexuality.

Such recent readings of Wood’s work draw from the myriad competing analyses that have occupied and confounded Wood scholars over the last 80-odd years. Many of those analyses emerged only after Wood’s premature death, from pancreatic cancer, in 1942, but others swirled around him during his lifetime. Wood had a contentious relationship with the critics, who accused him of being everything from a rube to communist to a fascist. He also contended with scarcely disguised homophobia. In truth, Wood did flirt with a kind of populism when it came to art, which critics easily exploited to discredit him and his work. And yet, some of the paintings in which that populism comes to the fore are among his most challenging and memorable works.

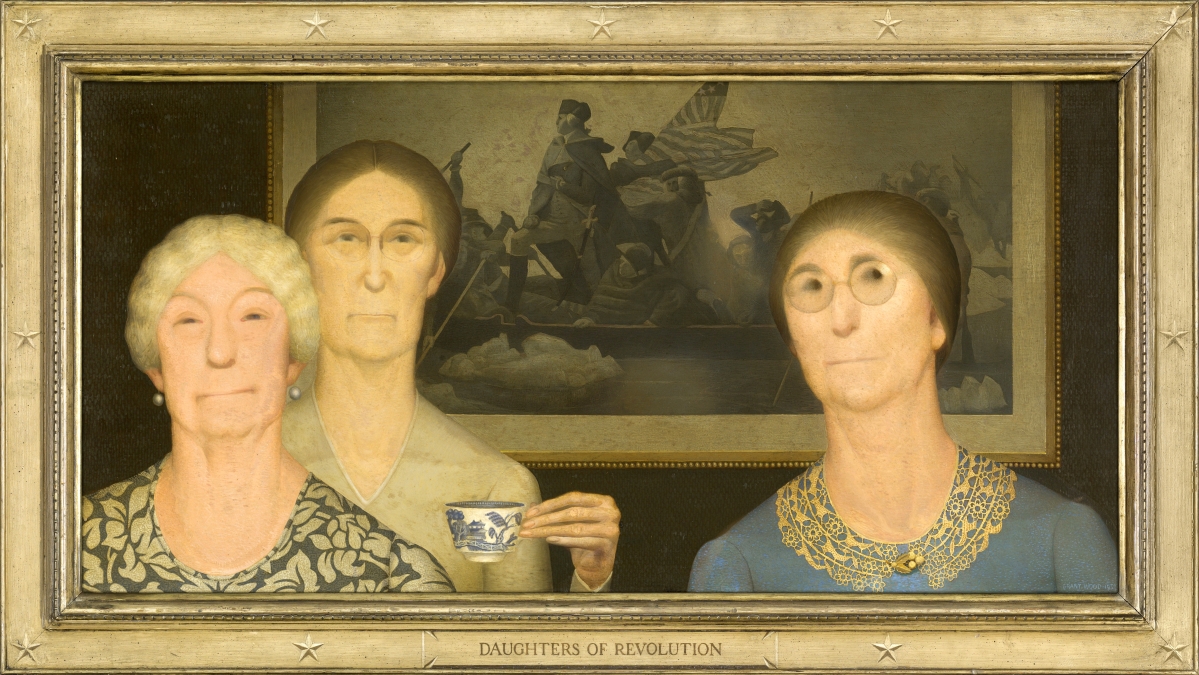

An illustrative example is his “Daughters of Revolution,” which debuted in the 1932 Whitney Biennial. Depicting three shriveled and thin-lipped denizens of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), posed as if they had literally crossed the Delaware alongside General Washington, the painting is, in the words of a contemporary critic, “as delicious as it is wicked.” The DAR itself agreed with the latter descriptor but not the former. They demanded that it be removed from a subsequent exhibition claiming it was “un-American.” Wood’s response was a veritable eye-roll, counter-accusing them, fairly enough, of trying to establish an American “aristocracy by birth.”

Something similar is going on with “The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover,” purportedly memorializing the ancestral pile of the president whose policies, by then, had resulted in utter economic ruin throughout the Midwest. Can Wood really have meant to enshrine this relatively ordinary-looking farmhouse in the annals of American history as the birthplace of a “great man”? The discerning viewer must think not.

But Wood was not always so cynical. “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” was completed the same year as “The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover.” It shares the same aerial view (“balcony perspective,” Reece-Hughes calls it) and rounded, precisionist landscape forms. But there is a deep sense of narrative and a certain breathless magic here – the nightgowned figures stepping out of their front doors, the horse and rider, modeled on a child’s toy, seemingly levitating back out into the night. This kind of decorative embellishment and storytelling – the “fables” of the exhibition’s title – Haskell says, was “anathema” to Modernists like Lincoln Kirstein and fellow artist Stuart Davis. If Wood must create narrative, representational works instead of abstractions, they argued, he gravely erred in failing to show more of the grim realities of Depression-era rural life.

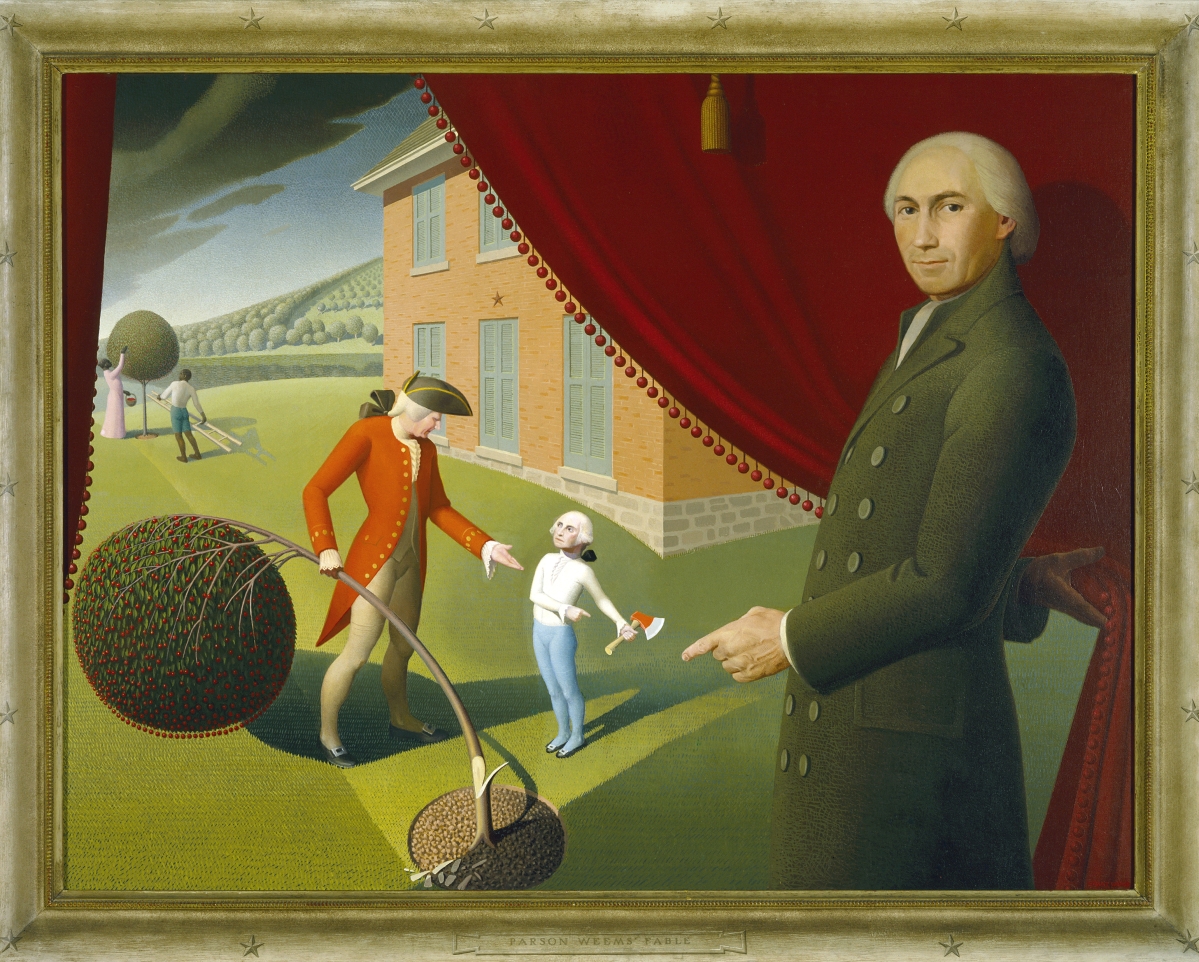

But Haskell counters that “he wasn’t attempting to paint real life.” This is obvious, of course, in his semi-fantastical historical works – his other Art History 101 painting is “Parson Weems’ Fable,” which depicts the familiar story about George Washington and the cherry tree and, creepily (as Braun would say), gives Washington the boy the head of Washington from the dollar bill. But this is also true of Wood’s pure landscapes, with their swelling hill forms and orderly rows of sturdy-looking grain anchoring complex geometrical compositions.

“What [the critics] didn’t quite understand,” Haskell argues, “is that Wood wasn’t painting Iowa in the 1930s – he was painting his imagined memory of the farm that he lived on in the 1890s” – and sometimes, it must be acknowledged, an imagined memory of a rural, colonial past. How different are his views of America’s sacred spaces and founding fables than his depiction of the self-appointed keepers of the same in “Daughters of Revolution” – and how greatly, in turn, must his stories have differed from theirs.

The Whitney Museum of American Art is at 99 Gansevoort Street. For information, www.whitney.org or 212-570-3600.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama , the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.

.jpg)