“Strollers at the Lake II” by August Macke (1887-1914), 1912, oil on canvas. Neue Galerie New York City. Collection of Estée Lauder, made available through the generosity of Estée Lauder.

By Kristin Nord

NEW YORK CITY —The master collector and director of Neue Galerie, Ronald S. Lauder, has said that he categorizes art into the separate categories of “My,” “Oh My” and “OH MY GOD,” reflecting his increasing determination that his collections, which, at last count, number 17, will be “the best of the best.” It is his connoisseurship and the museum’s over-arching philosophy that makes visiting the Neue Galerie such a satisfying experience.

For this season, the first floors of the magnificent former home of Mrs Cornelius Vanderbilt on East 86th Street has left its landing and decorative arts galleries intact. The visitor is treated here to glistening silver, gold and glass objects, to its paintings by Oscar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt making unforgettable appearances, and to armchairs and polished cabinets functioning very much like sculpture. Mouth-blown crystal of astonishing delicacy, objets d’art and Josef Hoffman’s brooches of agate, almandine, carnelian, moonstone and lapis lazuli transport visitors to the Belle Epoch and to the virtuosity of Viennese artists and craftsmen. Next, exquisite mantle clocks direct the eye to the dazzling portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, the Byzantine-influenced Klimt masterpiece so many visitors have come specifically to see. The painting was commissioned in 1903 by Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, a wealthy Jewish Viennese industrialist and the husband of its 25-year-old subject. It figured prominently in one of the largest cases of Nazi-looted art restitution ever and later became front page news in 2006 when Lauder bought it on behalf of Neue Galerie, for $135 million dollars.

Installation view of “German Masterworks from the Neue Galerie.” Image courtesy Neue Galerie New York. Annie Schlechter photo.

Over the years, Lauder has been drawn to Austrian and German Expressionism not only for the strength of the works, but for their capacity to capture the artists’ inner worlds: “They are highly personal, unexpected and often challenging — encouraging the viewer not only to look but to feel.”

As Janis Staggs, the curator of “German Masterworks,” explained, “The lovely German word, Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, represents the ethos for how we display the collection and attempt to create a unique experience for our visitors, where all elements work together in harmony.”

Gesamtkunstwerk is in full force in the two complementary shows — “German Masterworks from the Neue Galerie” and “Austrian Masterworks from the Neue Galerie,” which delve into the art and ideas from 1890 to around 1940. The “German Masterworks” portion will be in situ through May 4.

By the early part of the Twentieth Century, Berlin had become a major cultural center; and, by 1905, with its 2 million inhabitants, it had become the third-most populated city in Europe, following Paris and London.

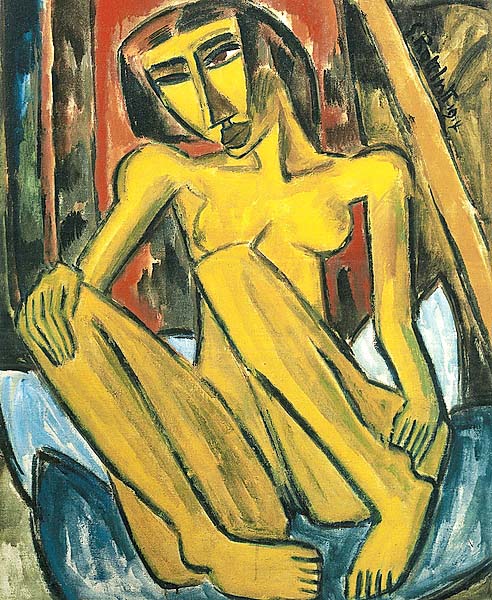

“Young Woman with Red Fan” by Max Pechstein (1881-1955), circa 1910, oil on canvas. Neue Galerie, New York City. Collection of Estée Lauder, made available through the generosity of Estée Lauder.

Norbert Wolf wrote, in his book, Expressionism, that around 1905, “German artists appeared to be bringing what were seen as their Faustian gifts into modern art with a revolutionary verve, finally establishing a counter weight to the French avant-garde.”

At this time, the art historian Jill Lloyd, in German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity, observed, “The speed and drama of modernization in Germany at the end of the Nineteenth Century meant that many of the dilemmas and contradictions showed up in bold relief.”

The modern era had pushed the traditional pictorial concepts of painting to their limits. “A street isn’t made out of tonal values, but is a bombardment of whizzing rows of windows, of screeching lights between vehicles of all kinds and a thousand jumping spheres, scraps of human beings, advertising signs and shapeless colors,” the artist Ludwig Meidner wrote. And the growth and change in this part of the world seemed to spawn whole art movements and theories.

First came Die Brücke, established in 1905, when its leading members — Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff — turned to simplified or distorted forms and unusually strong, unnatural colors to jolt the viewer and provoke an emotional response. Next came the Blaue Reiter — or Blue Rider group — established by Russian artist Vasily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and August Macke, artists whose work was fueled by personal theories.

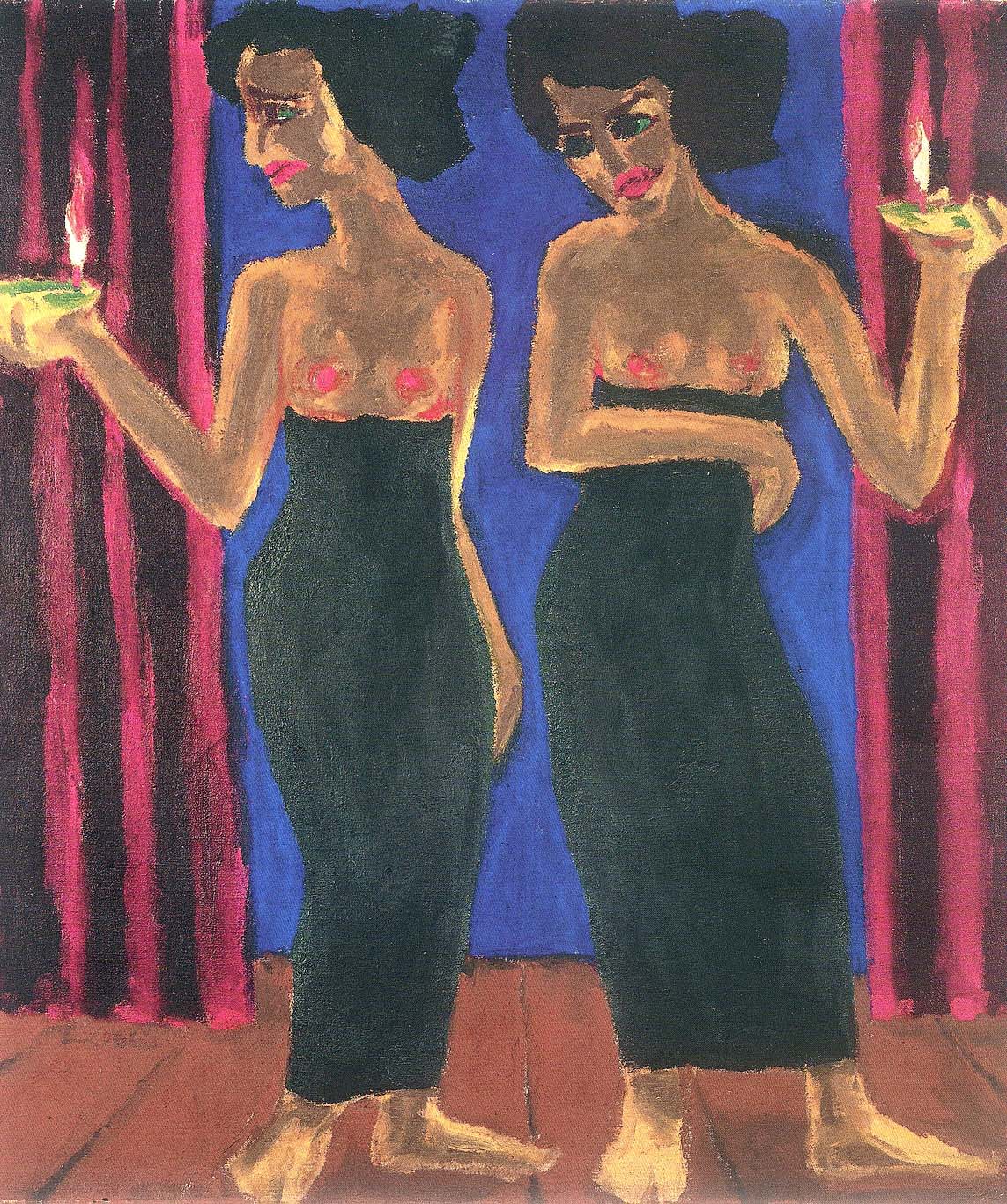

“The Russian Dancer Mela” by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), 1911, oil on canvas. Private Collection.

Kandinsky saw colors as living forces with their own intrinsic “sounds” whose immediate effect on the psyche was to be released and represented in the purist manner possible. Marc depicted animals — not just as subjects of artistic exploration, but as vessels of spiritual meaning, and believed their forms were imbued with cosmic significance. Macke, who would become known for his civilized urban scenes, did not share Marc’s pantheism, his art, too, was fueled by the vision of an earthly paradise.

At the same time, the Expressionists’ visits to ethnographic museums in Dresden, Hamburg and Berlin provided additional fuel for debate and conversation. “These were not one-off voyages of discovery but rather an integral part of their working lives,” Lloyd noted. “Just as the positive evaluation of primitive art and society as a regenerative force depended on a particular constellation of values which both attacked and reconfirmed evolutionary codes, so too the late Nineteenth Century approach to modernity was complex and ambivalent. And there was a “strong vein of nostalgia… a longing for a lost organic unity between art and life,” she wrote.

On a visit to the Neue Galerie, the jade-colored gallery beams with the shock of this era’s new paintings: Vasily Kandinsky’s “Murnau: Street with Horse Drawn Carriage”; August Macke’s “Strollers at the Lake II”; Gabriele Munter’s “White Wall,” Franz Marc’s Fighting Cows” and “The First Animals”; Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s “Tightrope Walk”; Max Pechstein’s “Young Woman with Red Fan” and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s “Landscape with Houses and Trees (Dangast before the Storm).”

“Tightrope Walk” by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), 1908-10, oil on canvas. Neue Galerie New York.

Kirchner and Meidner were both drawn to and appalled by aspects of urbanization and the dangers of an approaching war. Kirchner’s street scenes of prostitutes along Potsdamer Platz became emblematic of German big-city Expressionism and were matched by the darkness of Meidner’s frightening self-portrait, “I and the City” and his apocalyptic “Landscape” series.

Successive galleries, in which the walls turn from terracotta to white, move visitors through to the New Objectivity Movement and on to the time when the Bauhaus School began to make its revolutionary mark.

One can’t help but sense Sigmund Freud’s presence in the art of Oskar Kokoshka, who “stripped the mask of centuries from the human image. Full of nervous ligatures and physical distortions,” his portraits, Wolf wrote, amounted to “a laying bare of the sitter’s soul.” Then there is the portrait by George Grosz , in which the contours of his subject’s face appear as a constellation of pulsing veins. Christian Schad’s “Two Girls” and Georg Grosz’s “Couple in Interior” suggests that these artists, too, were illustrating the psychoanalytic ideas of the day as produced work that explored the connection between sexuality and the creative act.

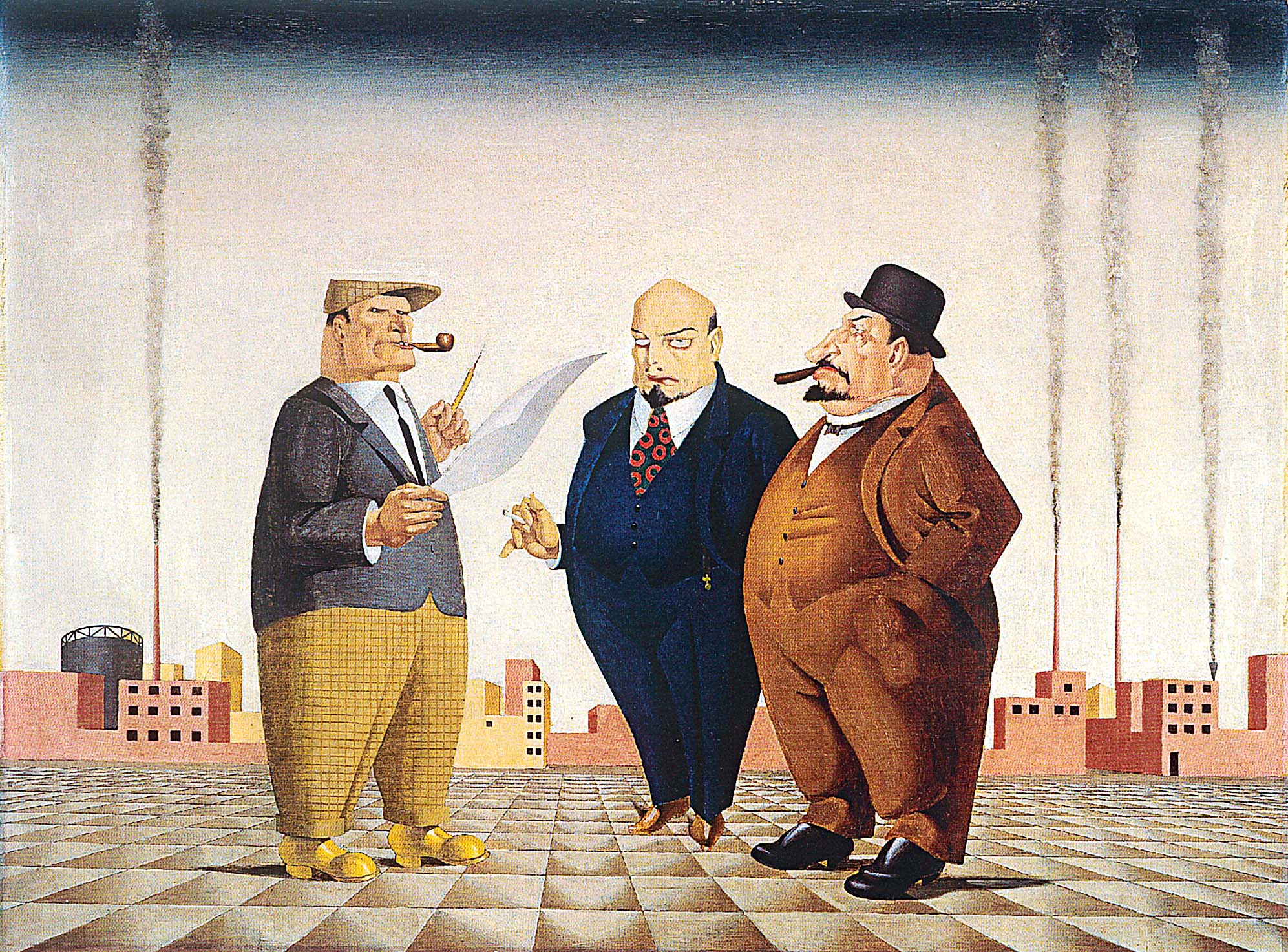

“Panorama (Down with Liebknecht)” by George Grosz (1893-1959), 1919. Private Collection, courtesy Neue Galerie, New York.

Under the Weimar Republic, Otto Dix and Georg Scholz generated blisteringly satiric political works that challenged aspects of urban life and the blind pursuit of capitalism.

Against this complex theoretical backdrop, there were other pure originals, like the Swiss-born Paul Klee, a virtuoso violinist who made it his mission to translate the fundamental structures and rhythms of musical composition into painting.

“One day I must be able to improvise freely on the keyboard of colors: the watercolors in my paintbox,” he said.

Klee continued to develop his ideas at The Bauhaus School, founded 1919 in Weimar by Walter Gropius, It was there that Klee developed his color spectrum, square and polyphonic painting series and he and other gifted faculty sought to redefine the relationship between art and industry. Gropius envisioned a “new guild of craftsmen,” a place where artists, designers and craftsmen could come together to create functional and aesthetically pleasing objects that served the needs of modern society. The Bauhaus’s minimalist aesthetics, functional art and sustainable practices became touchstones for art and design that have continued to be a part of the mainstream.

“Gay Repast Colorful Meal” by Paul Klee, 1924, oil on canvas. Private Collection.

After the school closed in 1933, many of its legendary teachers escaped from Nazi Germany and assumed arts leadership roles in the United States and elsewhere.

The diversity of the artwork associated with the Bauhaus is vividly illustrated in this show in such canvases as Lyonel Feininger’s “The Blue Cloud,” Paul Klee’s “Town Castle” (1932) and László Moholy-Nagy’s “A XI” of 1923. The influence of designers Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, Theodor Bogler, Marianne Brandt and Wilhelm Wagenfeld, can still be felt today.

Neue Galerie opens a door to the complexities of Modern European art history and challenges us to see the world as these artists did. In the process, we can’t help but notice parallels with our own time — of ongoing economic disparity, the rise of anti-semitism and what seems to be an incurable penchant for war.

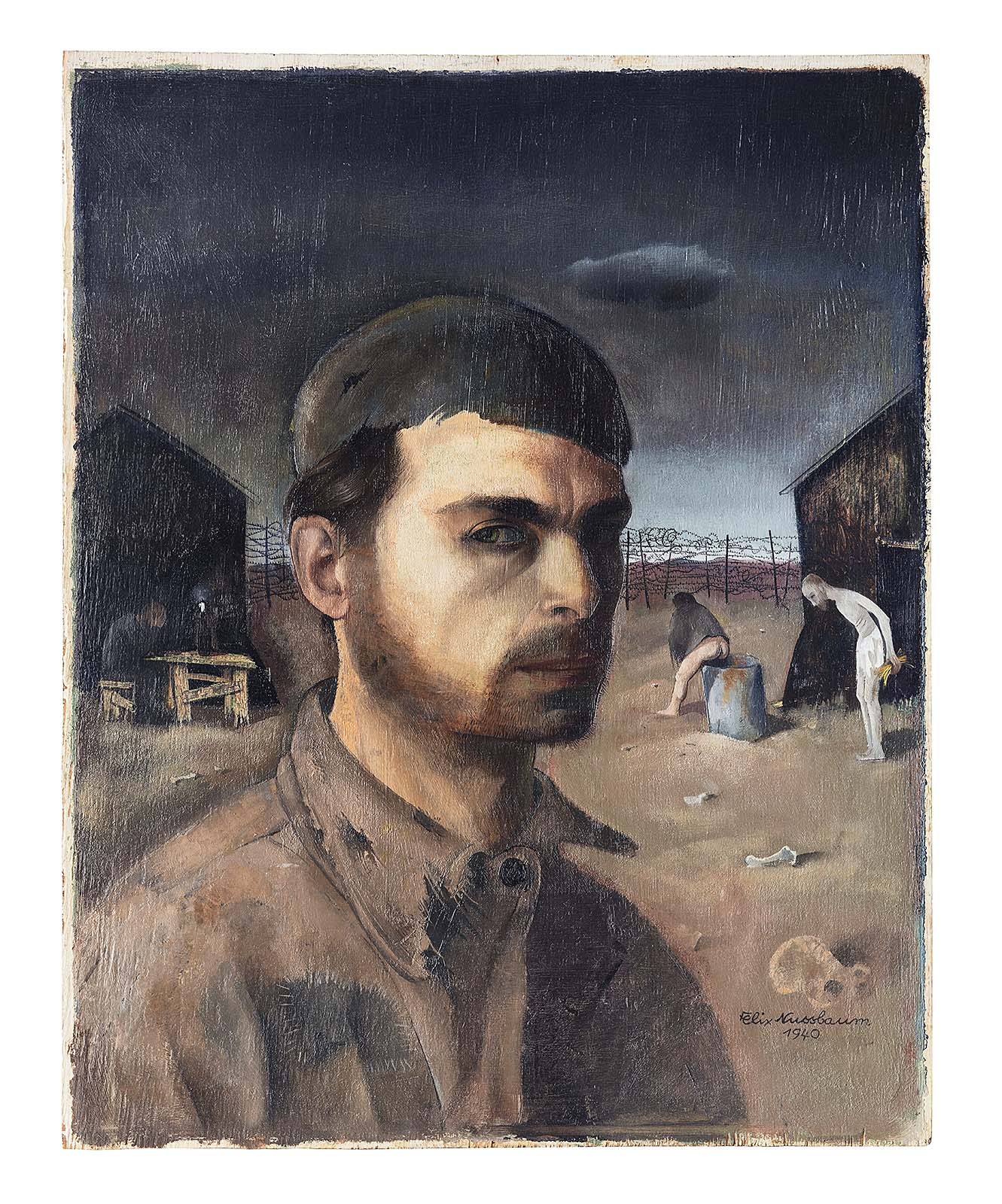

In a final gallery, long ago photo images of many of the luminaries we’ve just encountered are to be found. These portraits invite us to reflect on their lives, their ideas and their art. The lone oil painting in the gallery is a self-portrait of Felix Nussbaum, an artist who was sent from the prison camp in France, which he depicts, to his death. The juxtaposition between his art and his death can’t help but linger with us.

“German Masterworks” is on view through May 4.

The Neue Galerie is at 1048 Fifth Avenue. For information, www.neuegalerie.org or 212-994-9493.