Favrile Beetle Necklace designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848-1933) and Meta K. Overbeck (American, 1881-1946), made by Tiffany Furnaces (Corona, N.Y.), between 1913-32, Favrile glass, pressed and iridized and silver-gilt metal. Supported by The Ennion Acquisition Fund. Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass.

By Carly Timpson

CORNING, N.Y. — At the turn of the Twentieth Century, scientific advancements led to an explosion of color across Europe and America. New discoveries in chemistry in 1856 led to synthetic, chemically produced dyes, which invited a new visual spectrum to take over virtually all industries. In response, glass manufacturers had to respond to consumer demands for more color. While intricate cut and engraved glasswares were all the rage throughout the majority of the Nineteenth Century, the developments in full-spectrum glassmaking meant that manufacturers were able to respond to the sensational changes in consumers’ tastes and fashions — leaving clear brilliant cut glass behind, and uplifting the now-accessible cameo, iridized, heat-sensitive, dichroic and metameric glasses.

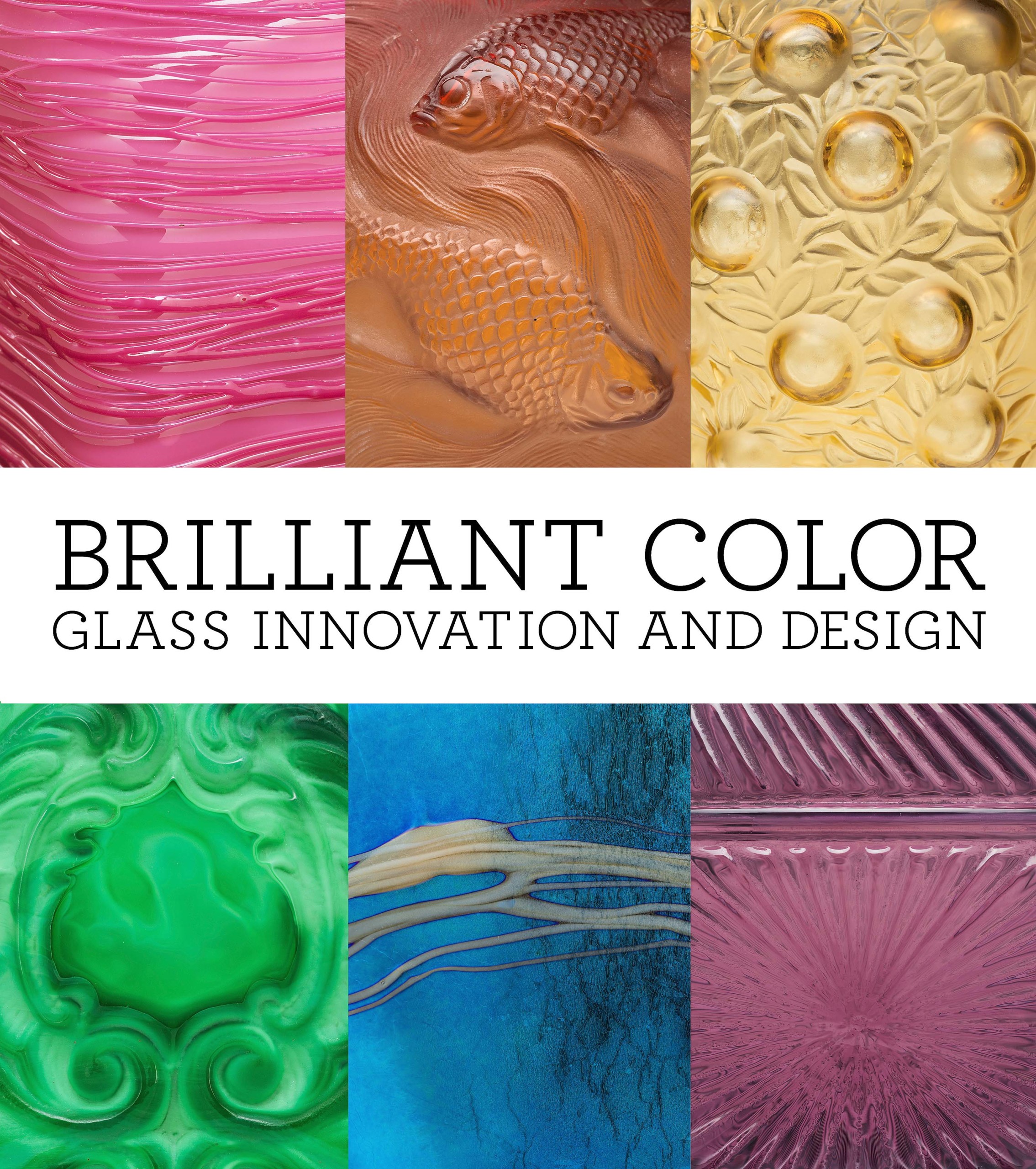

In a new exhibition, the Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG) explores this color revolution, highlighting the science behind the different techniques and the makers at the forefront of the revolution both in Europe and America. Curated by Amy McHugh, “Brilliant Color” presents around 140 objects from CMoG’s permanent collection and is paired with extensive research from the Rakow Research Library — which has one of the largest collections of batch books (glass recipe books) — to fully explore the technical processes behind the visible colors.

Karol Wight, president and executive director at the museum, said, “We are excited to present an exhibition that plays to our strengths: our expansive collection, which encompasses and illustrates key moments of innovation in 3,500 years of glassmaking; contextual materials and deep institutional knowledge from the Rakow Research Library; and our relationships with contemporary artists that continue to push the boundaries of what glass can do.”

Footed Bowl designed by Harry Northwood (American, 1860-1919), United States, about 1910, dark amethyst iridescent glass, pressed in a mold. Gift of Mr and Mrs Carlton Schleede. Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass.

McHugh, who joined CMoG as curator of modern glass in 2023, shared, “Shortly after coming on board, I was tasked with the opportunity to develop the 2025 Special Exhibition. I was both excited and overwhelmed by the possibilities offered by the rich and vast modern collection. One day, while strolling through the 35 Centuries of Glass Galleries, a dramatic shift in colors caught my eye. The earth-toned glass in the Ancient and Islamic sections transitioned into gem-toned glass of the Early Modern period.”

She continued, “In the Nineteenth Century European and American glass sections, objects incorporating aquamarine, pink and green were intermingled with the colorless, brilliant cut-and-engraved glass. These works transitioned to the bold shades of the heat-sensitive glasses of Mount Washington Glass Company and New England Glass Company, the vibrant colors of Steuben, Tiffany Studios’ harmonious nature-inspired palette and the rich jewel tones of René Lalique. Color suddenly infused the galleries, colors that were not present 50 years before!”

In the past few decades, scholars have researched and presented findings on the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century ‘Color Revolution’ as it pertained to textiles and paint or ink-based media, the development of colored in glass from a scientific lens and how specific firms developed their colored glass. However, McHugh endeavored to explore the color movement as it relates to glass more broadly — that is, to uncover what the specific changes were, who was responsible for the changes and how the objects were incorporated into everyday life. In short, “‘Brilliant Color’ is a celebration of all glass that is colorful, not just the luxury glassmakers of the modern era like Tiffany, but also of the more common, affordable table glass that the average consumer could access.”

Niijima 10/99-B1 by Klaus Moje (German, 1936-2016) in Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 1999; translucent deep blue, opaque deep blue, red, green, yellow, light blue and “black” glass, kiln-formed, hot-worked, ground, cut, polished. 14th Rakow Commission, purchased with funds from the Juliette K. and Leonard S. Rakow Endowment Fund. Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass.

Responding to the demand for colorful glass with novel decoration techniques, glass manufacturers endeavored to develop new formulas and employed a suite of new methods such as fuming, spraying, layering and heating to mimic colors and patterns found in synthetic dyes, historic designs and nature. McHugh added, “Through endless experimentation, they perfected innovative formulas and processes for manipulating colors, registering patents to claim these colors and processes as their own creations. They publicized their chromatic successes and revolutionary designs to colleagues, competitors and consumers at international expositions and world’s fairs.”

Divided into four sections, the exhibition starts by highlighting the new “Color Wall.” In this first display, viewers are greeted by a large-scale display of vibrantly colored glass objects alongside their original glass recipes, makers’ notebooks and information about their methods from the Rackow Research Library, to showcase the fundamentals of colored glass.

McHugh explained, “Glass is colored naturally by its ingredients — sand (silica), soda ash (sodium carbonate) and limestone (calcium carbonate) — whose impurities can tint the glass blue, green or even brown.

But glassmakers can intentionally create specific colors with additives such as oxides, elements or minerals incorporated into the molten batch.” For example, gold can be added to make red glass, cobalt for blue glass and cadmium sulfide for yellow glass. These varieties and the experimentation that led to their development are further explored in “Color Innovation.” This section presents makers’ never-before-seen colors and styles that were eventually shared and replicated to become mainstays in the industry.

Bowl manufactured by Boston and Sandwich Glass Company (Sandwich, Massachusetts), about 1870-88; yellow and amber non-lead glass, free-blown. Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass.

Examples on display include cameo-carved glass, heat-sensitive glass, iridescent glass and glass designed to resemble patterns in stone or minerals, such as malachite or rose quartz.

Another innovation of the era was light-sensitive glass, which is explored in “Color Innovation.” One of McHugh’s most highly-anticipated sections, she describes the experience: “You will enter a darkened ‘room’ with opportunities to view glowing uranium glass, dichroic glass transmitting and reflecting certain wavelengths and a case of four metameric objects. Metameric glass changes color based on whether the object is illuminated by full-spectrum light — daylight — or fluorescent light — the lighting found in offices or stores. The case will be lit so the vases will change color in front of your eyes.”

Expanding on the research process that went into this section, McHugh noted, “While we knew some of these objects were metameric, the extent of the color changes were revealed during the photography process, and we were able to identify additional collection objects as metameric! The museum’s incredible photographer Andy Fortune set to work lighting a pair of Moser vases for new photos. As he moved the light along, the vases’ colors kept changing. The vases are spectacular objects, and we captured a video of the color shifts to share with the exhibition team. Later, I asked Andy to confirm that a Lalique vase was dichroic and he answered with ‘I hate to tell you, but it’s metameric instead of dichroic…’ It is great to discover new layers of these beautiful objects. We conducted additional testing with two vases and glass samples produced by Moser, and we discovered that each piece had different compositions. This just reveals that further research needs to be done on metameric glass to understand its compositions and what materials make certain colors.”

Alexandrite Vase designed by Heinrich Hussmann (German, 1897-1981), made by Karlsbader Kristallglasfabrik A.G. Ludwig Moser & Söhne und Meyr’s Neffe, in Czechoslovakia (present-day Czechia), about 1928-30, Alexandrite (neodymium) glass, mold blown and cut. Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass.

Finally, the exhibition closes with a glimpse into how the advancements made during the Color Revolution have persisted and continues to develop today. “Color Today” considers how glassmaking has changed through the Twenty-First Century and shines light on makers such as fused glass trailblazer Klaus Moje, legendary cast glass duo Jaroslava Brychtová and Stanislav Libenský and other influential artists. In this section, visitors will see the lasting impact of the Color Revolution’s discoveries and how colored glass and once-novel techniques are used in everyday life from architecture and décor to tableware and kaleidoscopes.

The exhibition’s fully illustrated companion volume by the same name includes four essays that further emphasize the innovation and development of colored glass at the turn of the century. McHugh’s two essays — “A Spectacular Spectacle: Colored Glass At Nineteenth Century World’s Fairs” and “Every Color In The Rainbow: Table Glass Marketing Of The 1910s And 1920s” — delve into the emergence of colored glass at world fairs in the Nineteenth Century and the resulting rise of American manufacture in respond to consumers’ demands.

Glass historian James Measell’s “Immigrants And Innovations: Art And Chemistry Come To America From England” outlines the ways in which English immigrants Harry Northwood (1860-1919), Joseph Locke (1847-1936) and Frederick Carder (1863-1963) “charted new directions with their innovations in a wide variety of glass colors and their range of interesting designs for functional glass tableware and decorative glass items. Their continued efforts to create new products in colored glass changed the face of the American glass industry.”

Vase designed by Heinrich Hussmann (German, 1897-1981), made by Karlsbader Kristallglasfabrik A.G. Ludwig Moser & Söhne und Meyr’s Neffe in Czechoslovakia (present-day Czechia), 1927-30; blown glass, sandblasted and acid-etched. Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass.

CMoG assistant curator Amy J. Hughes’ “Kinetic Colors For Modern Times: Leo Moser’s Alchemy Of Art And Science” explores the intersection of art and science, specifically in Leo Moser’s innovative “glass colored with rare earth elements, whose colors change in different lights.”

As visitors experience the chromatic journey of “Brilliant Color,” McHugh hopes they see the impact of color development during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century, especially understanding how much experimentation and technological variation went into developing the colors we see in glass today, knowing how integral chemistry is to the entire creation process.

“Brilliant Color” is on view at the Corning Museum of Glass, 1 Museum Way, through January 11, 2026. For information, www.cmog.org or 607-937-5371.