Seen at front right is a funerary mask by an unknown Paracas Cavernas artist, possibly collected on the South Coast of Peru, 300 BCE-1. Ceramic, resin, and pigments. Brooklyn Museum. Frank L. Babbott Fund and Dick S. Ramsay Fund. Photo Jonathan Dorado.

James D. Balestrieri

Anthropogenic climate change. Climate crisis. Climate migration. Environmental depredation. Colonial and corporate exploitation and exhaustion of natural resources. Extinction of species, biomes, peoples and cultures. It belies a reality beyond nonsensical gibberish like “Chinese hoax;” where weather and climate are not one and the same; where a line is traced between Manifest Destiny, the forced removal and extirpation of Indigenous peoples, and the rapidly accelerating climate crisis. Herein we find the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition “Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas,” on view through June 20, 2021. Before you go, though, I would urge you to read up on the Dakota Access Pipeline, built to move tar sands oil from Canada to refineries in Texas, across and under land belonging to the Standing Rock Sioux in North and South Dakota. After a long legal battle and high-profile protests that were met with attack dogs, water cannons, and militarized private security in violation of the Constitutional right to peaceful assembly, the pipeline – which was a great concern to the Standing Rock people, not only because it desecrated burial grounds and sacred sites, but because it ran close to the tribe’s source of fresh water – was completed. Predictably, as the Standing Rock people and every environmentalist feared, there have been leaks in various places along the pipeline route, including one in 2017 that released 407,000 gallons of oil at the edge of Standing Rock land. I would further urge you to read David Grann’s non-fiction book, Killers of the Flower Moon, which chronicles the discovery of oil on Oklahoma land – not very good land – given to the Osage. With this discovery, many of the Osage became celebrated millionaires overnight. But there was a catch. The Osage were given court-appointed guardians – there were actual adoption papers – who were, wait for it, all white men. Soon, the Osage began to die in violent and mysterious ways: by the gun, by fire and by poison. Conspiracy among these self-styled “friends of the Osage” ran dark and deep as Oklahoma crude.

The opening wall text defines the scope of the exhibition, which “explores the effects of the climate crisis on both Indigenous communities and the planet as a whole. A central concept here is environmental colonialism, which considers the cumulative impact of land seizures, government and corporate development projects, and accelerated natural resource extraction over the past 500 years. This history is manifested today in environmental problems such as wildfires, droughts, glacial melt, scarcity of resources, displacement of Native peoples and violence against Indigenous communities and activists.” A range of historic and contemporary works in the exhibition span from the high Arctic to South America and highlight a wide variety of cultural, spiritual and economic connections between Indigenous peoples and the natural world.

The Nasca – more familiarly known as Nazca because of the enormous “Nazca lines,” geoglyphs in the Peruvian desert of creatures and shapes best seen from the air, whose meaning is a matter of debate – inhabited what is now the southern coast of Peru between 100 BCE and 800 CE. They are known not only for the Nazca lines but for their vast irrigation system and complex textiles and pottery, such as the beautifully formed and decorated double-spout vessel dated to 325-340 CE. Depicting the Nasca’s Mythical Being, or “masked god,” who holds peppers and a club in one hand and the severed heads of two enemies in the other, the vessel unites fertility and protection. Lest we think that overfarming and Dust Bowls are Twentieth Century phenomena, it is speculated that when the Nasca cut trees to increase agricultural production, they exposed the land to the erosive effects of El Niño storms and that this contributed to their ultimate decline. Success succeeds until it doesn’t. Even the gods can’t save us from ourselves.

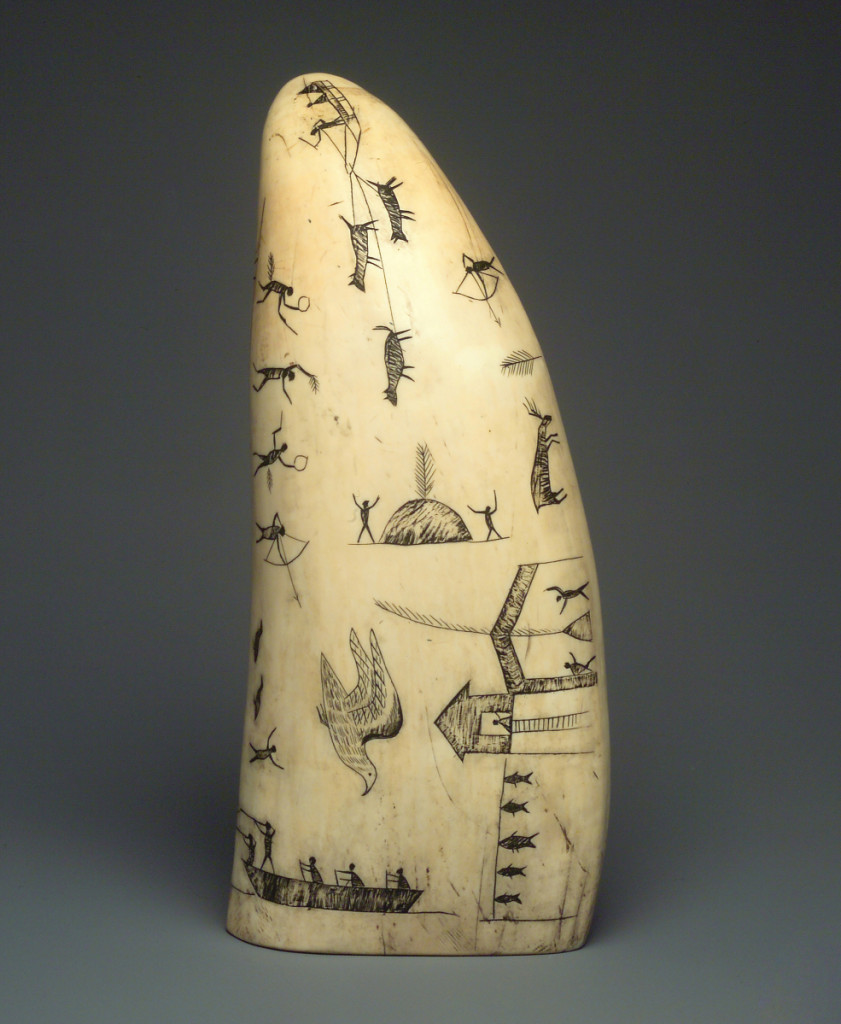

Engraved whale tooth by Alaska Native artist, late Nineteenth Century. Sperm whale tooth, black ash or graphite, oil. Brooklyn Museum. Gift of Robert B. Woodward. Creative Commons-BY. Photo Brooklyn Museum.

Reverence for the natural world, a word that combines gratitude and fear, is epitomized in the Aztec sculpture, “Reclining Jaguar,” fashioned out of volcanic stone. Carved sometime between 1400 and 1521, just before Cortez came to displace the Aztec reliance on the power of the jaguar – and the elite jaguar warriors – with the cross and sword, even the material the smiling cat is made from commands reverence. The ash from volcanoes makes for fertile soil and volcanic stone is a formidable thing to build with, yet these same volcanoes, stirred from slumber, can destroy empires faster than Conquistadors. The Indigenous understanding of balance and respect, contained in the idea of reverence, is key to their relationship to nature.

Gold is what Cortez, Pizarro and their contemporaries came to the (not so) New World for, and gold is what they found, though none discovered the fabled city of gold, El Dorado. Among the Indigenous peoples of Mexico, Central and South America, gold was often used to make ceremonial objects such as the Coclé Plaque with Crocodile Deity that would have been worn by members of the elite to symbolize their kinship with their central deity. Still, the Inca, for example, did not understand the Spanish obsession with gold. Compared with the feathers of the Quetzal, or set alongside intricate textiles, gold was revered not as valuable in itself, but because of the aesthetic and spiritual value of the objects that were made from it.

Shifting north, to the Northwest Coast and to Alaska, two works related to whales – one from an anonymous Nineteenth Century Indigenous artist, the other from noted contemporary Tlingit artist Preston Singletary – speak to the intertwined way in which the whale has traditionally sustained communities in the region as a source of economic, spiritual and artistic well-being. Images on the engraved whale tooth encapsulate hunting, fishing and the activities of daily life in the community. Fish dry on a line, farmers raise their hands in the joy of growing things, hunters with bows and snares pursue caribou and gamebirds. Engraved on whale ivory, the scenes suggest that the whale is the all-embracing wellspring of abundance and prosperity.

Baleen whale mask by unknown Kwakwaka’wakw artist, Nineteenth Century. Cedar wood, hide, cotton cord, nails, pigment. Collected from Knight’s Inlet, British Columbia Canada, museum expedition 1908. Museum Collection Fund. Photo Jonathan Dorado.

Hunted to near-extinction – first for their oil, used in lamps, and then for their meat and ambergris – by American, Russian, Norwegian, Icelandic and Japanese whalers, among others – the sense of balance between utility and veneration has, for many years, been tipped. The whale was just another resource. Had petroleum not replaced whale oil in the world’s lamps, the whale might well have gone the way of the passenger pigeon. The fragility of nature makes its presence known in Singletary’s 2004 rendering of a whale, “Guardian of the Sea.” Drawing on the geometries of Northwest Coast Indigenous art, Singletary’s whale, in alternating red and black – also in traditional colors – departs from tradition in one key aspect: it is fashioned of glass, emphasizing the very fragility of our relationship with the natural world.

Lastly, Kiowa artist Teri Greeves updates the tipi in “21st Century Traditional: Beaded Tipi.” Beaded with images of Indigenous people in modern dress beneath the moon, stars and other symbols of nature and the heavens, the scenes of parents holding and playing with children indicate a people who thrive in spite of change, people who are taking charge of change.

We tend to think of climate change as something that – like war – happens far away from us, far from the United States, or as something our great-grandchildren will have to deal with. But the incessant wildfires on the West Coast and in Colorado, the excessive heat of the Southwest, the tropical storms and hurricanes that have exhausted the alphabet, the pattern of drought and flood in the Midwest, the migrations of people from once-fertile areas of Central America, the Middle East, and Africa, are bringing the science – which doesn’t care whether we believe in it or not – home to us, to the United States. Fast. Waves of climate migration might well mark the history of our future, and the tipi – an elegant, beautiful, functional, portable structure, evolved over centuries – might well become our idea of home.