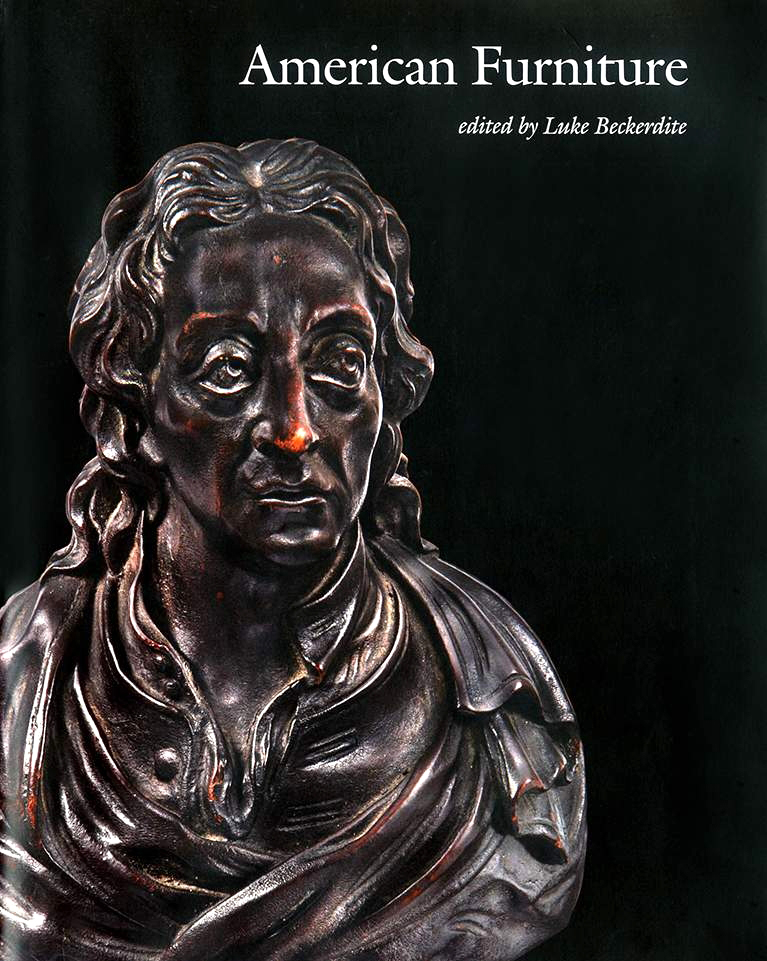

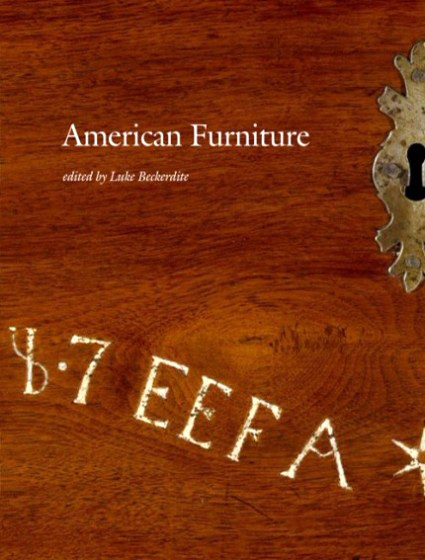

American Furniture 2016, edited by Luke Beckerdite, with contributions by Luke Beckerdite, Alan Miller, Moira Gallagher, June Lucas, Margaret K. Hofer, John Fiske, Richard Oedel and Gerald W.R. Ward. Published by the Chipstone Foundation, distributed by University Press of New England; 190 pages, hardcover, $65.

The 16th volume of Chipstone Foundation’s much lauded annual journal ranges from east to west and north to south, beginning with Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller’s study of a wood bust Chipstone Foundation purchased at Sotheby’s Important Americana sale in January 2016. Beckerdite and Miller undertook a methodical study of the carved work, cataloged simply by Sotheby’s as American school. Employing a variety of investigative means, they concluded that the sculpture is by the celebrated Philadelphia carver Martin Jugiez.

Beckerdite follows his examination of the Franklin bust with “Thomas Johnson, Hercules Courtenay and the Dissemination of London Rococo Design.” He begins his essay with the paradoxical observation that there is no documented example of work in wood or any media other than paper by Johnson, “one of the most influential rococo designers in the English-speaking world…” Carving by Johnson’s former apprentice and journeyman Courtenay is known, prompting Beckerdite to evaluate the careers of both men and the roles they played in disseminating style.

Moira Gallagher moves far forward into the Nineteenth Century with an exhaustive account of the contributions of the hitherto little known Gilded Age cabinetmaking firm George A. Schastey and Company, the subject of a recent exhibition and publication organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

New work by June Lucas, Old Salem Museum and Garden’s director of research, considers the early furniture of North Carolina’s Cane Creek Settlement. Quakers in large numbers settled in five North Carolina counties, collectively known as the Quaker Crescent, in the second half of the Eighteenth Century. Much of Lucas’s inquiry focuses on the workshop of Joseph Wells (1729–1804), a member of Cane Creek Meeting, the North Carolina Piedmont’s oldest Quaker community, settled in 1750–51. Sulfur-inlaid furniture attributed to Wells’ shop suggests the influence of Pennsylvania as well as the mingling of English and Germanic forms.

In the volume’s final essay, Beckerdite and Margaret K. Hofer flesh out the biography of Stephen Dwight, identified as the probable maker of the carved frames surrounding Lawrence Kilburn’s 1762 portraits of New Yorkers James and Jane Beekman. The authors offer new documentary evidence supporting earlier attributions, placing Dwight “at the forefront of carvers active in New York City during the third quarter of the Eighteenth Century.”

Book reviews contribute additional heft. They include John Fiske’s look at the revised 2016 edition of Victor Chinnery’s essential treatise Oak Furniture: The British Tradition: A History of Early Furniture in the British Isles and New England; Richard Oedel’s favorable introduction of the new Mortise & Tenon magazine, devoted to “working wood by hand solely by traditional methods,” and Gerald W.R. Ward’s entertaining discussion of the equally lively Now I Sit Me Down: From Klismos to Plastic Chair: A Natural History by Witold Rybczynski, professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the best-selling books Home: A Short History of an Idea and The Most Beautiful House in the World.

As always, Gerald W.R. Ward’s meticulous compilation of recent writings on American furniture is much appreciated.

—LB

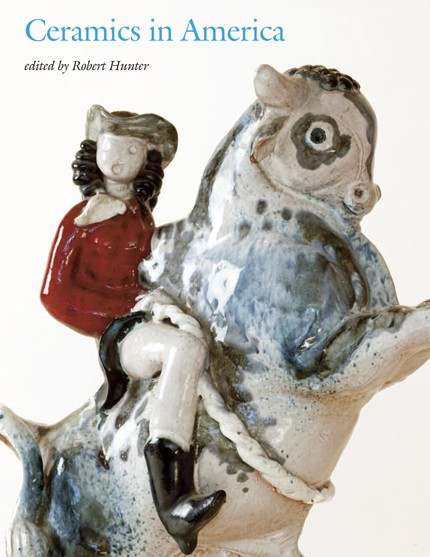

Ceramics in America 2015, edited by Robert Hunter, with contributions by Robert Hunter, Russell K. Skowronik, Ronald L. Bishop, M. James Blackman, Michael Imwalle, Ruben Reyes, Shirley Mueller and Edward A. Chappell. Published by the Chipstone Foundation, distributed by University of New England Press; 216 pages, hardcover, $65.

It is axiomatic that the more substantial the text, the slower the reviewer. Thus it is with an apology that we only now turn our attention to the well-crafted 2015 edition of this admired annual journal.

Editor Hunter begins his introduction with the observation that for all Ceramics in America’s variety, the publication has been slow to recognize the contributions of the American West. With that, he heralds an extensive analysis of the architectural tiles, bricks and domestic pottery produced in Alta California under Spanish control from 1779 to 1849. Presented by Russell K. Skowronik, Ronald L. Bishop, M. James Blackman, Michael Imwalle and Ruben Reyes, the study, conducted over multiple years, merges historical and archaeological research with practical demonstrations of the making and firing processes.

Pottery was largely unknown in the coastal region stretching between Los Angeles and San Francisco prior to the arrival of the Spanish in 1769. The ceramics studied here date from the period of Spanish and Mexican rule, which introduced the creation and use of ceramic vessel and terracotta building materials.

The report looks closely at tin-glazed pottery — variously called maiolica, mayólica or majolica — found from San Diego to north of San Francisco, some of it exported to the area from Puebla and Mexico City. The authors write, “One of the more significant findings of the research is the demonstration that some glazed wares associated with the missions and presidios were manufactured in Alta California and that they were manufactured at several of [what are now] museum complexes.” The researchers conclude, “It was not the glazed pottery that traveled but rather technology, first north from Mexico and then through the mission chain.”

In all, the team examined nearly 2,000 sherds recovered from nearly three dozen Spanish colonial and Mexican Republican-era sites. The team suggests as a future research direction a deeper look at the documentary record for the use and manufacture of lead-glazed pottery in Alta California.

A shorter essay by Shirley Mueller offers a fascinating look at Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), a collector of Asian art, and C.T. Loo (1880–1957), the dealer in Chinese porcelain who supplied him with exceptional pieces of sometimes murky provenance. “Whether Loo was Savior or Satan for China’s cultural artifacts…depends on one’s perspective,” Mueller writes. The author, after extensive study of Loo’s correspondence with Freer, finds little to admire in the dealer’s professional comportment.

She writes, “Loo had continued to be a ‘bad boy’ dealer despite Freer’s considerable efforts to teach him American standards and ethics. It was the perceived financial unfairness of the dealer by buyers Freer and [Eli] Lilly that led each to distance himself from Loo.” Mueller concludes of Loo, “…his failure to adopt the kind of professionalism Freer tried to impart to him has also tainted his legacy as the premier dealer of Asian art in America in the first half of the Twentieth Century.”

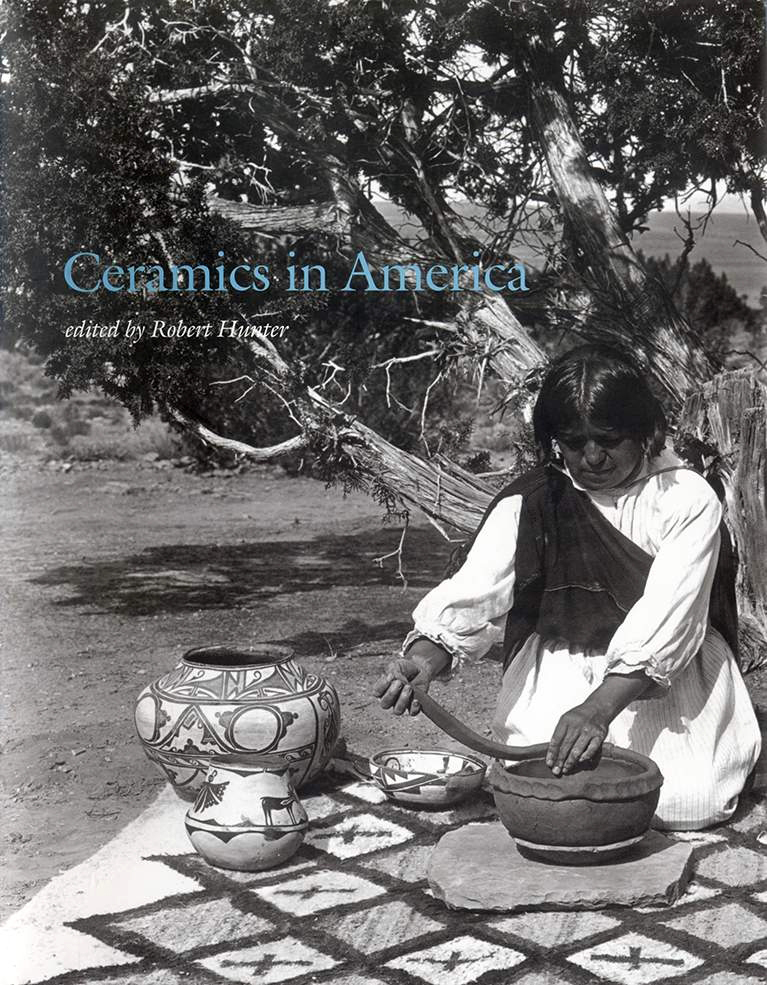

The final article, “Pride Flared Up: Zuni (A:shiwi) Pottery and the Nahohai Family” by Edward A. Chappell, returns to the American West, but in a different era. Hunter notes, “The history of collection and publication of Pueblo pottery is aligned with a cult of celebrity potters,” adding, “no single category of American-made ceramics has a greater bibliography…” For all that, the makers of most Pueblo pottery remain anonymous.

Chappell focuses his query on the Pueblo potters of Zuni, 55 miles from Gallup in New Mexico. The centerpiece of his study is Randy Nahohai and members of his immediate family. Chappell writes, “By working with a contemporary family of Zuni potters — the Nahohais — I have had the privilege to observe how elements of a larger culture take shape piece by piece, pot by pot, brushstroke by brushstroke, influenced by values shared by parents, children and kin as well as by choices, sometimes idiosyncratic and creative, made by the artists themselves…”

Chappell begins his article by teasing apart the post-contact influence of a few prominent European Americans from culturally untainted manifestations of Zuni art and belief systems. He introduces George Coleman, a Virginian who acquired wares directly from Zuni people in the 1920s, and Frank Hamilton Cushing and Matilda Coxe Stevenson, who arrived at Zuni in 1879 as part of the first organized expedition mounted by the Bureau of Ethnology. Chappell ends his essay by writing that the marketplace and cross-cultural exchange go only so far. He notes, “A thousand George Colemans might carry away the pottery of Zuni Pueblo, but its spirit remains at home.”

Hunter concludes his introduction with the frank acknowledgment that maintaining the print version of Ceramics in America in an era of growing digital dominance poses questions. He writes, “For the moment, the journal remains committed to its beautifully designed and printed format.”

We urge readers to support the cause. The main contents of this and other volumes are, however, also posted at www.chipstone.org.

—LB

By Kate Eagen Johnson

American Furniture 2015, edited by Luke Beckerdite. Published by the Chipstone Foundation, distributed by University Press of New England; 241 pages, hardcover, $65.

Chipstone’s American Furniture 2015 highlights craftspeople and techniques associated with Eighteenth Century Pennsylvania furniture-making. Like traditional Pennsylvania German cuisine, its contents are solid, substantial and tasty. The menu includes “Barnard Eaglesfield: A Prominent Philadelphia Cabinetmaker Revealed” by Jay Robert Stiefel; a photographic reproduction of the notebook of Philadelphia joiner John Widdifield with an explanatory introduction; “Sulfur-Inlaid Furniture: New Insights on Materials and Techniques” by Mark Anderson, Brenda Hornsby Heindl and Jennifer Mass; and “Sulfur Inlay in Pennsylvania German Furniture: New Discoveries” by Lisa Minardi.

Stiefel adeptly draws upon details contained in previously unpublished manuscripts to conjure up the circumstances and career of Eaglesfield (d 1732), a fine woodworker and proprietor of an active shop whose furniture was sought after in his day but for whom no identifiable pieces are known to exist. Indicative of the cabinetmaker’s first-rate reputation is the request from a merchant in Barbados to a ship captain that he obtain a scrutoire and two dining tables for him “from the best work man in Phila[delphia],” in other words, Eaglesfield. Stiefel lays a strong biographical foundation while also imaginatively combining what is known about Eaglesfield’s output with examples of early Eighteenth Century Philadelphia furniture. At the essay’s conclusion, this scholar points to research avenues that might lead to furniture produced by this overlooked player.

In their appealing article featuring the kind of delectable detail photography for which Chipstone publications are renowned, Anderson, Heindl and Mass offer scientific and technical analysis of the processes and ingredients used in the creation of sulfur-inlaid objects in America. At the time of publication, this artifact group consisted of more than 125 items made in southeastern Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina that bear dates as early as 1763 and as late as 1844.

For an exhaustive essay more than 100 pages in length, Minardi has conducted deep genealogical research on the initials and dates ornamenting the schranke, chests, tall case clocks, cupboards and other objects in this artifact group to determine possible owners and origins. She has organized some artifacts by regional style — for example, Lancaster County, Lebanon-Lancaster County Border, Tulpehocken Valley, Dauphin County and York County — and others by such varied topics as the Huber Schrank and related chests, objects with double-eagle inlay, slide top boxes and gravestones.

Minardi interlaces the theme of the changing nature of Pennsylvania German religious identification and association with furniture history and connoisseurship. A tall case clock acquired by the Chipstone Foundation in 2015 that possesses some commonalities with the sulfur-inlaid group serves as a case in point. Its movement is signed by Rudolph Stoner (1728–1769) and its pewter inlay may have been fashioned by Johann Christoph Heyne (1715–1781), both of whom were Moravian artisans working in Lancaster. As suggested by the inlaid initials and date, this confection was probably made for Frederick Stone, who married in 1762. In 1745, Stone’s father had been involved in a violent incident aimed at keeping the Lutheran congregation to which he belonged from joining with the Moravian Church in town. Less than 20 years later, this son of an anti-Moravian leader owned a Moravian-produced clock, a cross-denominational commission one might not expect to find. Minardi considers the object as emblematic of the lessening of religious tensions between Lutherans and Moravians during the mid-Eighteenth Century. Among other mitigating factors, Minardi explains that Lancastrians’ desire to better their community led them to deemphasize religious differences as they joined together in early civic organizations.

Reviews of Kem Weber: Designer and Architect; In Plain Sight: Discovering the Furniture of Nathaniel Gould; Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia and Early Seating Upholstery: Reading the Evidence push beyond the volume’s Pennsylvania focus and provide additional spice.

Like a big piece of Moravian sugar cake for dessert, Gerald W.R. Ward’s “Recent Writing on American Furniture: A Bibliography” completes this ample offering guaranteed to sate.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

Ceramics in America 2016, edited by Robert Hunter. Hanover and London: Published by the Chipstone Foundation, distributed by University Press of New England; 276 pages, 280 color illustrations, hardcover, $65.

This issue, the 16th in the Chipstone Foundation’s journal’s series, celebrates the theme of discovery. Editor Robert Hunter provides a valuable introductory overview to the volume’s 15 essays. Collectively, they represent more than three-and-one-half centuries of subject matter and sundry areas of study, including art history and theory, social and economic history, material culture, archaeology, chemistry and object conservation techniques.

The reworking and reimagining of ceramic artifacts and the use of scientific analysis to ascertain object composition stand as reoccurring topics. Representative of both is the essay “‘The most dangerous imitations’: A Group of Spurious Chinese Export Porcelain Decorated with Fame and the American Eagle” by Ellen Archie, Ronald W. Fuchs II, Jennifer Mass and Erich Uffelman. These experts investigate examples of late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century export porcelain which were altered to deceive during the 1920s. At that time, nefarious china painters removed the unexceptional decoration on these pieces and added the more-desirable motif of an Angel of Fame carrying the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization founded in 1783 by officers who had served in the Continental army and navy during the Revolution. These fakers, perhaps realizing there could be no more desirable pedigree, drew inspiration from the decoration found on George Washington’s own set of Society of the Cincinnati Chinese export porcelain.

The incriminating evidence — divided into the stylistic, the physical and the chemical — includes the nudity of the angel (which would have run counter to American sensibilities at the time), traces of the earlier decoration still visible in raking light and the identification of chemical elements through X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, which are not typically present in Chinese porcelain enameling of the era. The essay’s authors also caution collectors and curators about the pitfalls of overlooking past scholarship. As they point out, even though Homer Eaton Keyes had unmasked these forgeries in 1933 via an Antiques article titled “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft,” at least one scholar published a vessel with this disreputable decoration as authentic decades later.

Not all the artists and artisans whose talents and labors are featured remain in the shadows. Richard Miller contributes an engaging tale about the personalities, careers and decorated redware of Absalom Day, his nephew Asa E. Smith and Smith’s apprentice John Betts Gregory in “Norwalk (Connecticut) Slip-script Pottery, the Potters and Related Ware.” Ezra Shales has highlighted a trio of underappreciated Studio Craft potters in “Throwing The Potter’s Wheel (And Women) Back Into Modernism: Reconsidering Edith Heath, Karen Karnes and Toshiko Takaezu As Canonical Figures.” His essay grows from two exhibitions he co-curated in 2015, namely “Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft and Design, Midcentury and Today” at the Museum of Art and Design and “O Pioneers! Women Ceramic Artists, 1925–1960” at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum, Alfred University.

A sampling of essay titles indicates the volume’s “across-the-board” nature. Take, for instance, “George Thorpe’s Inventory of 1624: Virginia’s Earliest Known Appraisal” by Martha W. McCartney with photo essay “Ceramics in Early Virginia” by Beverly Straube; “The Allegory of Europa In Twentieth Century American Sculpture” by Tom Folk; and “Bonnin and Morris Revisited: The Geochemistry of a True-Porcelain Punch Bowl Excavated in Philadelphia” by J. Victor Owen, Joe Petrus and Xiang Yang. The last represents the roughly half-dozen essays where laboratory findings are central.

Amy C. Earls has edited a similarly eclectic collection of book reviews.

Those with highly specific interests within the realm of ceramics made and used in America may want to check out the table of contents online at UPNE Book Partners Chipstone Foundation: upne.com.

Otherwise, approaching Ceramics in America 2016 with open curiosity is recommended. There is much impressive research and interpretation here. Prepare to be surprised.