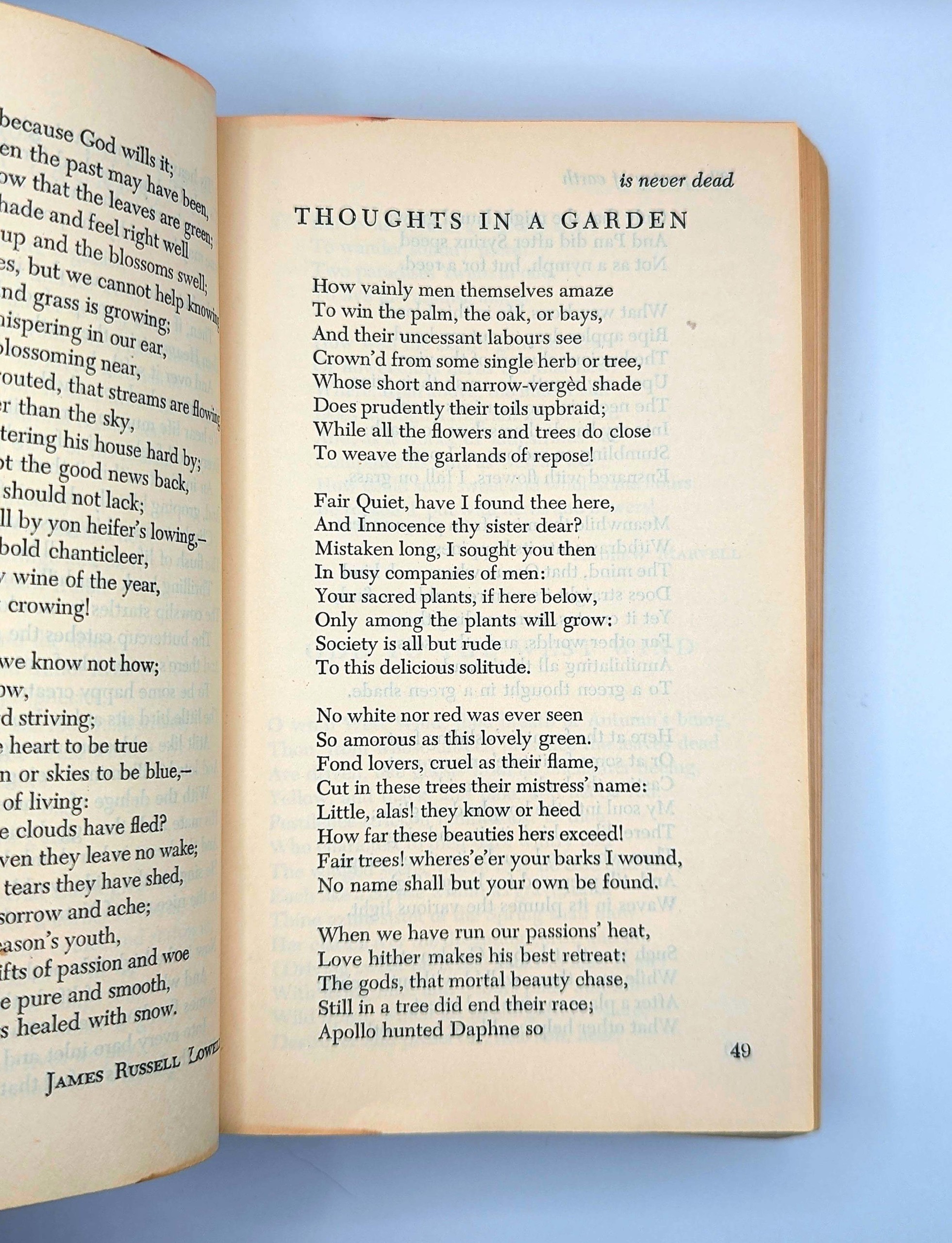

“Floral still life” by Martha Cahoon, oil on Masonite. Collection of Mary LeClair.

By Kay Koeninger

COTUIT, MASS. — There are literally hundreds of categories we can use to talk about art. Most of the time these categories work very well; sometimes they don’t. Often, artists do not fit neatly into one grouping. And some of the most intriguing artists fall into the “cracks” between classifications. One of these artists is Martha Cahoon (1905-1999), the subject of the new exhibition “Martha Cahoon: A Garden of Inspiration,” currently on view through December 21, at the Cahoon Museum of American Art on Cape Cod. The museum is located in the former home and studio of Martha and her husband Ralph (1910-1982).

Cahoon was the daughter and wife of well-known artists, but Leeann Ream, curator of the Cahoon Museum, created this exhibition to focus on Martha. In Ream’s words, “When I first began giving public talks and tours at the museum, audience members expressed a deep interest in learning more about Martha… The exhibition uses Marthas continued use of floral inspirations as a visual metaphor for how her artistic voice blossomed over time, providing visitors with the uniquely intimate perspective of a beloved Cape Cod artist.”

At first glance, Cahoon’s style seems to fit into the category of folk art; however, her place in American art history is more complicated. Folk art often applies to art made by anonymous artists, designed for a functional purpose. In contrast, Martha’s life story is well known, and her art was not always functional. Her parents were Swedish immigrants, and she studied with her father Axel Farnham (1876-1946), who ran a successful business restoring and painting antique furniture in Boston. Farnham relocated his family and business to Cape Cod in 1915.

“Farham Home, Main Street West Harwich” by Axel Farham, n.d., oil on glass. Gift of Gene and Judy Schott. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art.

Painted furniture has a long history in American art, beginning in the earliest Colonial period. In addition to being a means of personal expression, it had a very practical purpose: it could cover up inexpensive wood and imperfect, vernacular construction. There were many furniture variations by different Colonial immigrant communities; some of the best-known examples were made by the Pennsylvania Dutch settlers, who often incorporated folk art motifs from their European homeland. American folk art experts Robert Bishop and Jacqueline M. Atkins have pointed out that painted and decorated furniture was particularly popular in New England. Axel Farnham was an expert hemslojd, or handcraft, artist in his native Sweden and brought those skills to the United States. But unlike earlier American folk art furniture painters, Farnham’s work was meant for sale as art. In other words, his folk art had become “commodified,” taken out of its original functional context and placed in the world of collectors and interior designers. Farnham is represented by several works in the exhibition, including design samples and floral still life paintings. His regional home in Sweden was known for its plant- and floral-centered folk art paintings, which were called karbitsmalning and rosmalning.

Axel Farnham’s success was due, in most part, to his talent and the quality of the works of art he produced. But the time in which he lived was also conducive to the success of an artist focused on re-working older folk art styles. Many art historians, including Frances Pohl, have noted that a major folk art revival occurred in the United States from approximately 1910-20. In the face of record immigration to the United States, some American collectors were concerned with “alien influences” and sought out, instead, “true” American art. This quest, of course, ignored the fact that most of the folk art that they championed was produced by earlier immigrants. The exception to this rule was Native American art, which was also included in the folk art revival. Another aspect of this movement was a reaction against poorly made mass-produced objects and a new respect for the “hand-made” produced by authentic craftsmen and women.

Dome-top chest painted by Martha Cahoon, 1930, oil on wood. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art. Peter Julian photo.

Historical timing also favored the career of Farnham’s daughter, Martha. And like her father, her career is not easily located within accepted art classifications. A second folk art revival happened in the 1930s under FDR’s New Deal art programs. One of those programs, administered by the Federal Arts Project of the WPA, was the Index of American Design. From 1935 to 1942, 1,000 artists, all Federal employees, produced 18,000 watercolor illustrations of samples of American folk art from Colonial times to 1900. This collection focused on the work of American artists from European backgrounds. Concurrently, important aficionados of folk art during this time included Holger Cahill, the director of the Federal Arts Project, and important Modernist artists like Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1889-1953) and Elie Nadelman (1882-1946).

These developments clearly show how the 1930s were an opportune time for Martha Cahoon to become a successful artist in her own right. During this decade, she met and married Ralph Cahoon, a trained artist who specialized in drawing and painting, and they became business partners in their art and furniture company, which was also located on Cape Cod. Their product was folk art in style, but without the traditional cultural framework of folk art making. Like her father, Martha produced both painted furniture and two-dimensional paintings, while Ralph concentrated on landscape painting that often contained humorous and whimsical touches. As their work became more well known, the Cahoons became popular among New York collectors in the 1950s and were featured in prominent galleries, such as the Vose Gallery in Boston, in the 1960s.

Another historical shift that favored both Martha and Ralph Cahoon’s success was the movement of folk art into prominent museums. In the 1930s, the folk art revival went hand-in-hand with major East Coast exhibitions of folk art at the Newark Museum (now the Newark Museum of Art) and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. As is often the case, museum exhibitions are usually intrinsically connected to collecting by the wealthy and socially prominent. In terms of folk art, one of the best-known examples was Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who began collecting folk art in the 1920s, ultimately giving her collection to Colonial Williamsburg in 1935 to create the renowned Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

Portrait of Martha Cahoon by Harold Dunbar, circa 1922, oil on canvas. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art.

One of the most well-known results of both the folk art revival and museum elevation of folk art can be seen in the work of Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses (1860-1961), whose career in some ways parallels that of Martha Cahoon. She became famous in the 1930s, with her career taking off in the 1940s and 1950s. She specialized in folk art-style paintings of rural and small time life but did not do decorative painting of furniture. And, like Martha Cahoon, she was not a “naïve” artist; her father was a painter and she was inspired by Currier and Ives images. Her work was popular with prominent collectors and was included in museum exhibitions.

Pohl noted that Moses’ work was promoted overseas by the United States Information Agency as an example of “true American art” in the 1950s. Moses’ work was also featured in commercial galleries.

The continuing popularity of Martha and Ralph Cahoon is nurtured by the Cahoon Museum. In the Cahoon Museum’s current exhibition, visitors will be treated to a wide range of work, predominately by Martha Cahoon, but also art by her father and husband, as well as personal ephemera.

Martha’s painted furniture is characterized by a symmetrical, delicate touch and the use of a pale palette. Her unique floral oil on canvas paintings combined folk art elements of simplicity and flatness with the conventions of Baroque flower design. According to Ream, these works show that “She was a lover of nature, children and animals, and her work is tender, thoughtful and personal. Admirers of Martha Cahoon’s works are often drawn in by her idyllic beachside scenes, seasonal pastorals and — of course — colorful floral designs. It can be said that Martha truly did paint what she loved, and she was loved for it.”

Martha Cahoon’s painting, for some, is difficult to categorize. But she is a charming example of how artists who did not “fit” can create work that is timelessly appealing. She joined together the “fine” and the “folk,” making an important contribution to American art history that is firmly rooted in both time and place.

The Cahoon Museum of American Art is at 4676 Falmouth Road (Route 28). For information, 508-428-7581 or www.cahoonmuseum.org.