Tree of Life cut-out chintz quilt, probably Wiscasset, Maine, circa 1925-35, initialed “GMR,” cotton, 96 by 90 inches. Gift of Cyril Irwin Nelson in honor of Elizabeth V. Warren and Sharon L. Eisenstat, 2001.33.2.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

NEW YORK CITY — When the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) reopens on September 26, following a temporary summer closure for construction to their building and amid on-going larger-scale renovations anticipated to stretch to 2028, the special exhibition to inaugurate the revitalized space explores the natural history of American textiles. “An Ecology of Quilts: The Natural History of American Textiles” draws from the museum’s large collection of textiles, including more than 600 quilts, to survey the ecological and social consequences of agricultural production, industrial manufacture and international distribution networks, all of which allowed quilt-making to flourish into what the museum describes as a “quintessential American art form.”

“Our quilts collection encapsulates so many different makers, communities and time periods, it is brimming with possibilities,” noted Emelie Gevalt, AFAM’s deputy director and chief curatorial & program officer and the lead curator for the show. “One area that hasn’t received much targeted attention in recent years are the earliest quilts in our holdings, including examples from the late Eighteenth through the mid Nineteenth Centuries. The frequent botanical motifs found in these early examples became a springboard for us to think more deeply about the ecological implications of quilts, to turn our attention back in time from the story of the quilter, which usually forms the basis for quilting explorations, and consider the natural origins of textile materials and designs.”

The choice of the word “ecology” for the show’s title distinguishes the curatorial approach from other recent quilt shows. “[The show] takes an innovative approach by looking at the textiles from the very beginning of their manufacture process, highlighting the multiple hands around the world that have each participated directly or indirectly in the making of a finished quilt. By looking at quilts from multiple angles, including histories of technology, labor and global trade, the show also offers multiple points of entry, even for visitors who may come in thinking that quilts are not necessarily their favorite objects.”

Stenciled quilt by Olivia Denham Barnes (1807-1887) and Louisa Denham Farnham (1804-1833), Conway, Mass., circa 1830-31, cotton and paint. 83 by 72 inches. Gift of In the Beginning Quilts, Inc., Seattle, 2002.11.1.

Visitors will be welcomed to the exhibit by an exceptional cutout chintz Tree of Life quilt, attributed to Wiscasset, Maine, that was made around the first quarter of the Twentieth Century and promotes several points the exhibition touches on: the timelessness of botanical motifs, Eighteenth Century compositional elements, the incorporation of Nineteenth Century fabrics and the rainbow of colors most often associated with quilts.

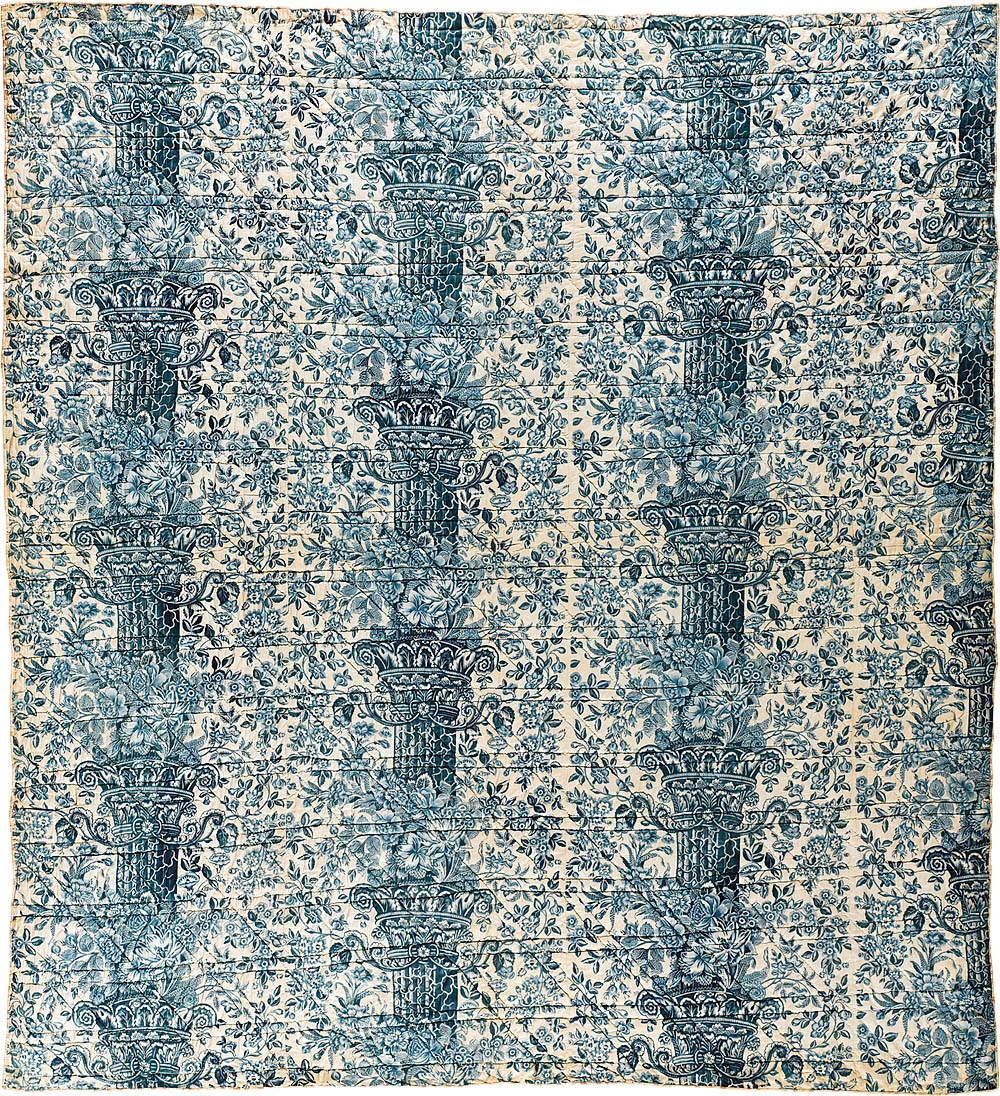

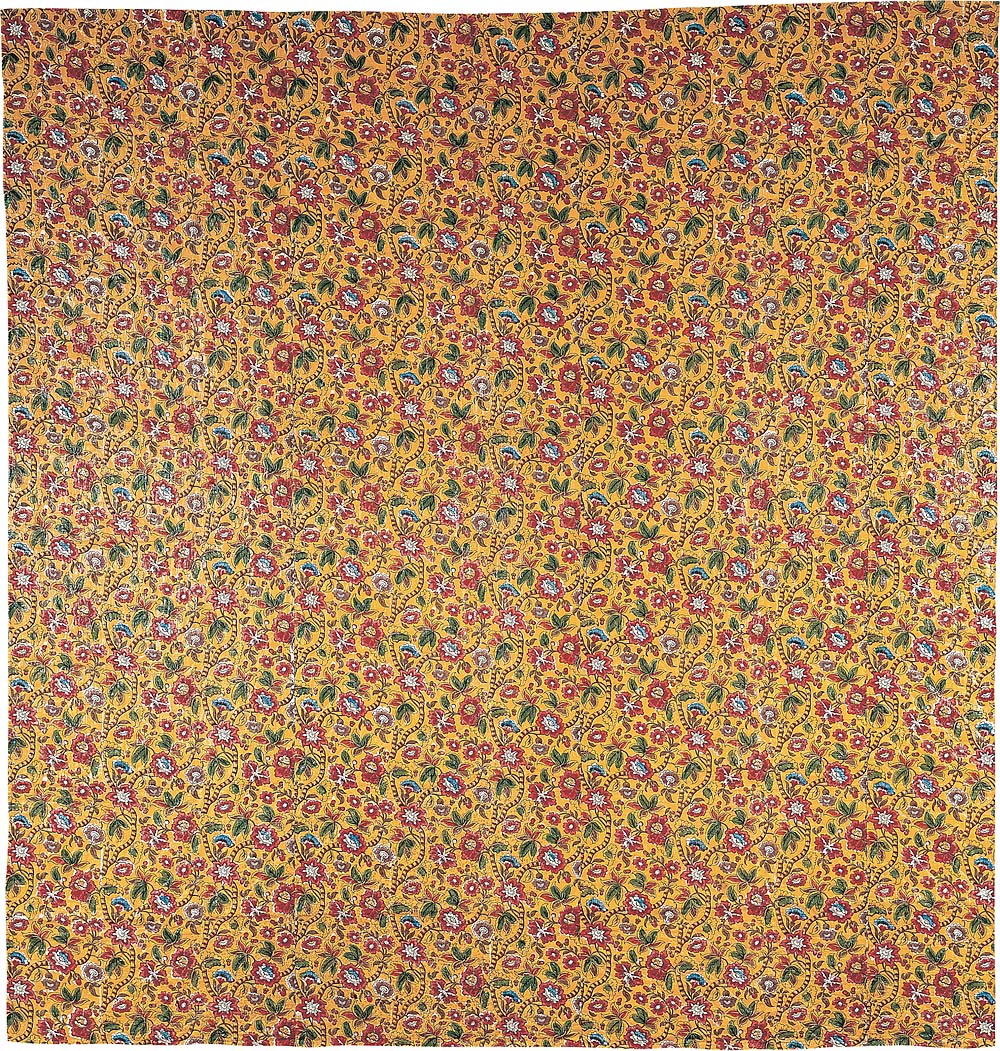

Noting that the history of textiles is, in part, a history of color, a section titled “Material Matters: Color” dives into the use of the indigo plant as one of the major historical dye sources for textile production; its use is seen in a beautiful Pillar Print wholecloth cotton quilt from the second quarter of the Nineteenth Century. Madder root or the cochineal insect, from which the natural carmine dye was extracted, produced the brilliant reds and oranges found in quilts such as a circa 1800 wool wholecloth quilt. The inclusion in the installment of a white Cornucopia and Dots whitework quilt explains the process for naturally blanching off-white fibers.

A profusion of flowers or meandering vine was often symbolic, representing the hope for a fruitful family in a marriage quilt; several quilts with family connections are prominently displayed, include a superb Vermont Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden example. A floral appliqué quilt made in 1856 and initialed “L.C.,” and a circa 1860 cotton and wool quilt copiously embellished with birds around a central pot of flowers also both demonstrate this.

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden quilt, attributed to a member of the Sinclair family, possibly Vermont, mid Nineteenth Century, cotton, 87 by 92 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by Nina Beaty, 2024.10.1.

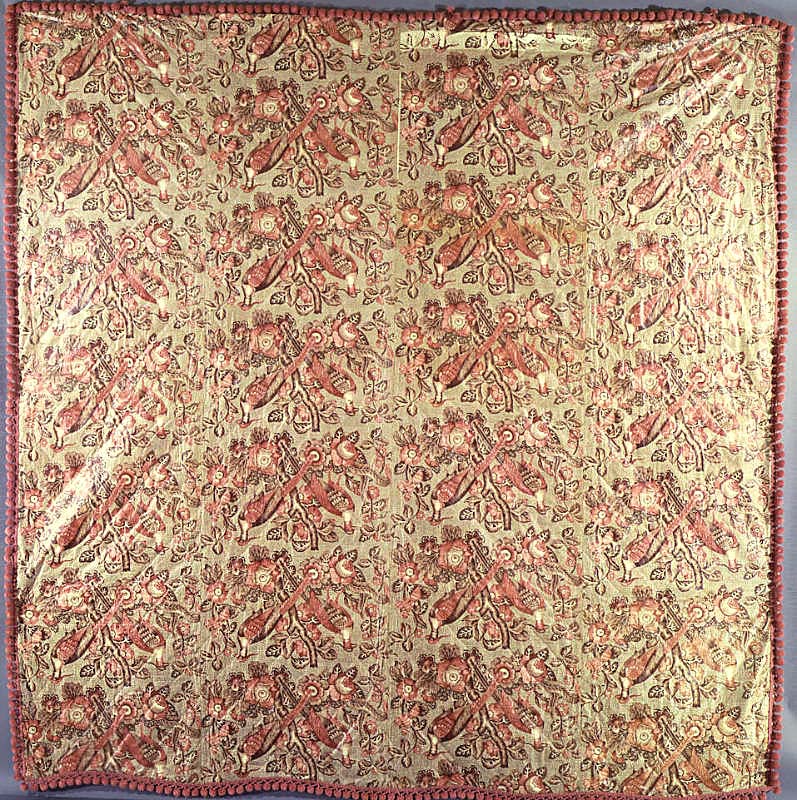

The evolution of printed patterns that came to the American textile market in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century brought with it an increasingly greater abundance of fabrics and designs, with chintz — a Hindi-derived term, most simply defined as “embellished cotton” — becoming a favored material with American quiltmakers.

Quilters with access to more expansive — and expensive — panels made wholecloth rather than pieced quilts that were often cherished among family members and stored, owing to a disproportionately high survival rate compared to workaday ones. Two such examples can be found in an early Nineteenth Century chintz quilt, made in England or the US, and one made by Elizabeth Higgs (1795-1872) that features a protective, lustrous glaze.

Lack of materials or the economy of space required quilters to employ creativity that contributes to the broad diversity of the form. A Flying Geese quilt, made around 1870, features unevenly pieced rows of chevron-shaped fabric alternated with bands of a dotted-blue printed cotton while a Log Cabin variation, made in Georgia around 1900, possibly by an African American quilter, shows an improvised use of tiny scraps.

A unique tied patchwork quilt with overshot coverlet, made in the late Nineteenth Century in Virginia or Maryland from cotton, wool and linen, as well as a quilt made out of woolen suiting samples by a Saint Louis, Mo., tailor both help demonstrate the use of recycled fabrics among quilters in a section titled “Economy and Excess.”

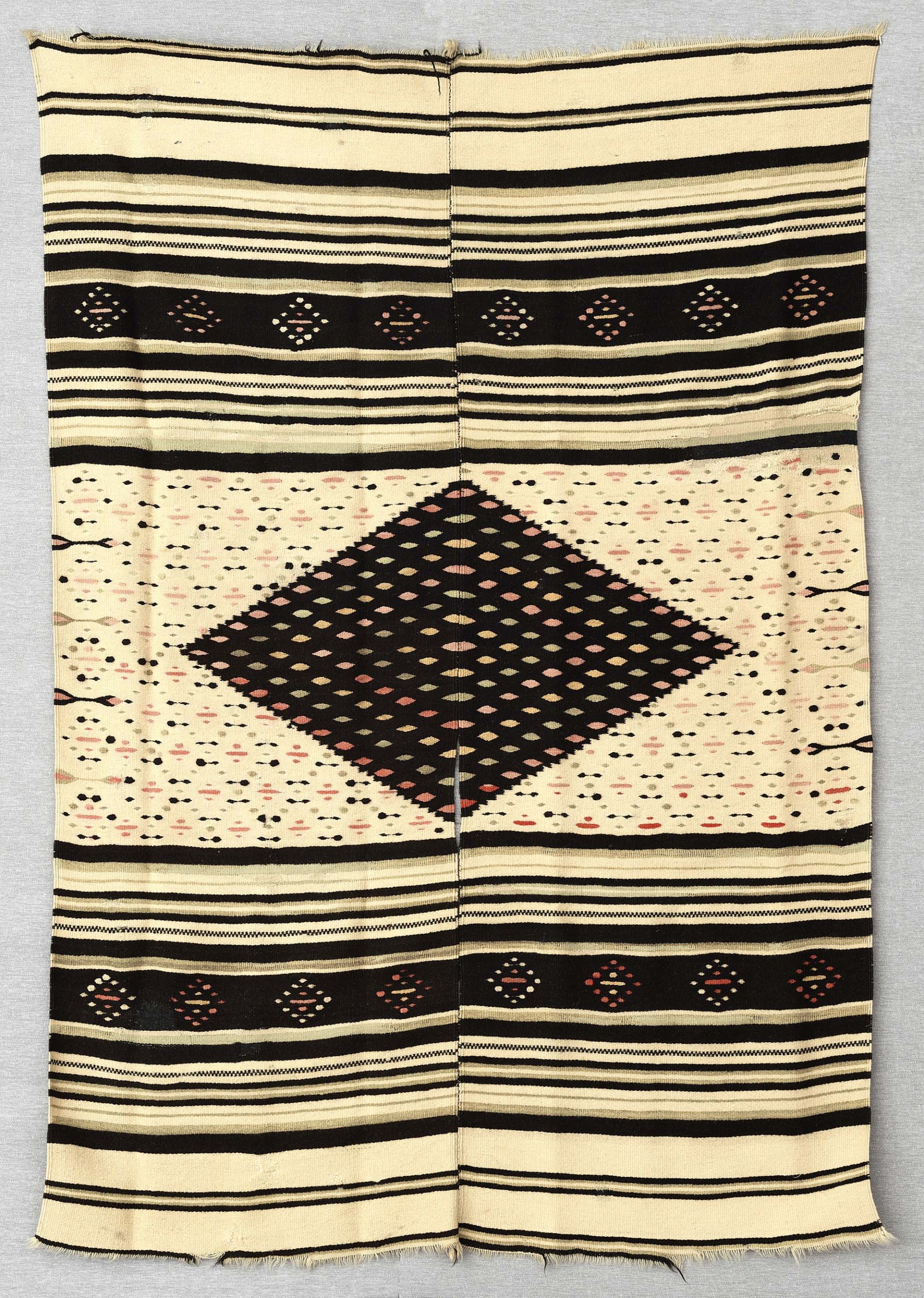

Central Diamond blanket, Oaxaca, Mexico, late Nineteenth Century, wool, 70 by 50 inches. Gift of Margot Paul Ernst in memory of Susan B. Ernst, 1989.16.20.

Quilting practices outside the Eastern United States contextualize the exhibition. A thick homespun wool blanket, made in Oaxaca, Mexico, in the late Nineteenth Century, features a central diamond, a common regional decorative motif, made from synthetic dyes to underscore new technologies weavers incorporated.

Representing a quilting tradition that originated in Hawaii, the show includes a Twentieth Century Oklahoma-made Mala Pua Aloha (Garden of Aloha) quilt that adapts the native botanical elements of torch ginger, hibiscus and breadfruit. A similar quilt referencing botanical specimens is in a mid Twentieth Century “album” example worked by Florida sociologist, Dr Raymond Bellamy.

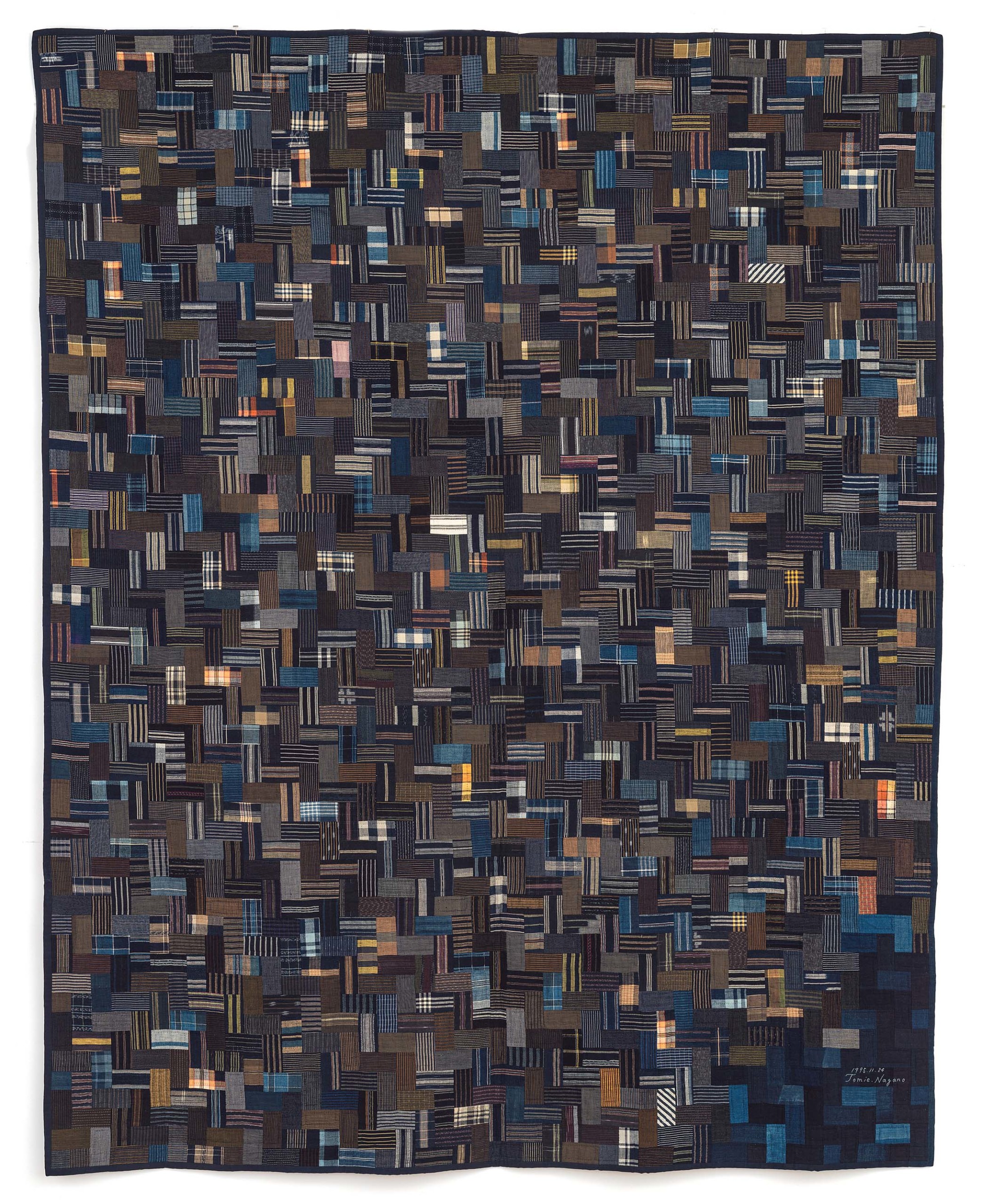

About a third of the AFAM show is new acquisitions, both recent purchases and donor gifts. Among these, an Ajiro-Monyo cotton quilt made by contemporary textile artist Tomie Nagano (b 1950), whose quiltmaking practice not only continues a family tradition of upcycling kimonos passed down from previous generations but is inspired by boro textiles (fabrics repeatedly mended out of economic necessity) and reflects the prevalent use of indigo dye in Japanese textile production.

Ajiro-Monyo by Tomie Nagano (b 1950), Shari, Hokkaido, Japan, and Dedham, Mass., 1995, cotton, 96¼ by 75 inches. Gift of Wayne E. Nichols, 2024.8.1.

Another comparatively recent addition to the collection also on view is Gee’s Bend quilter Malissia Pettway’s (1914-1997) Pinwheel Variation quilt, given to the museum in 2021, which blends both individual design ideas and established patterns.

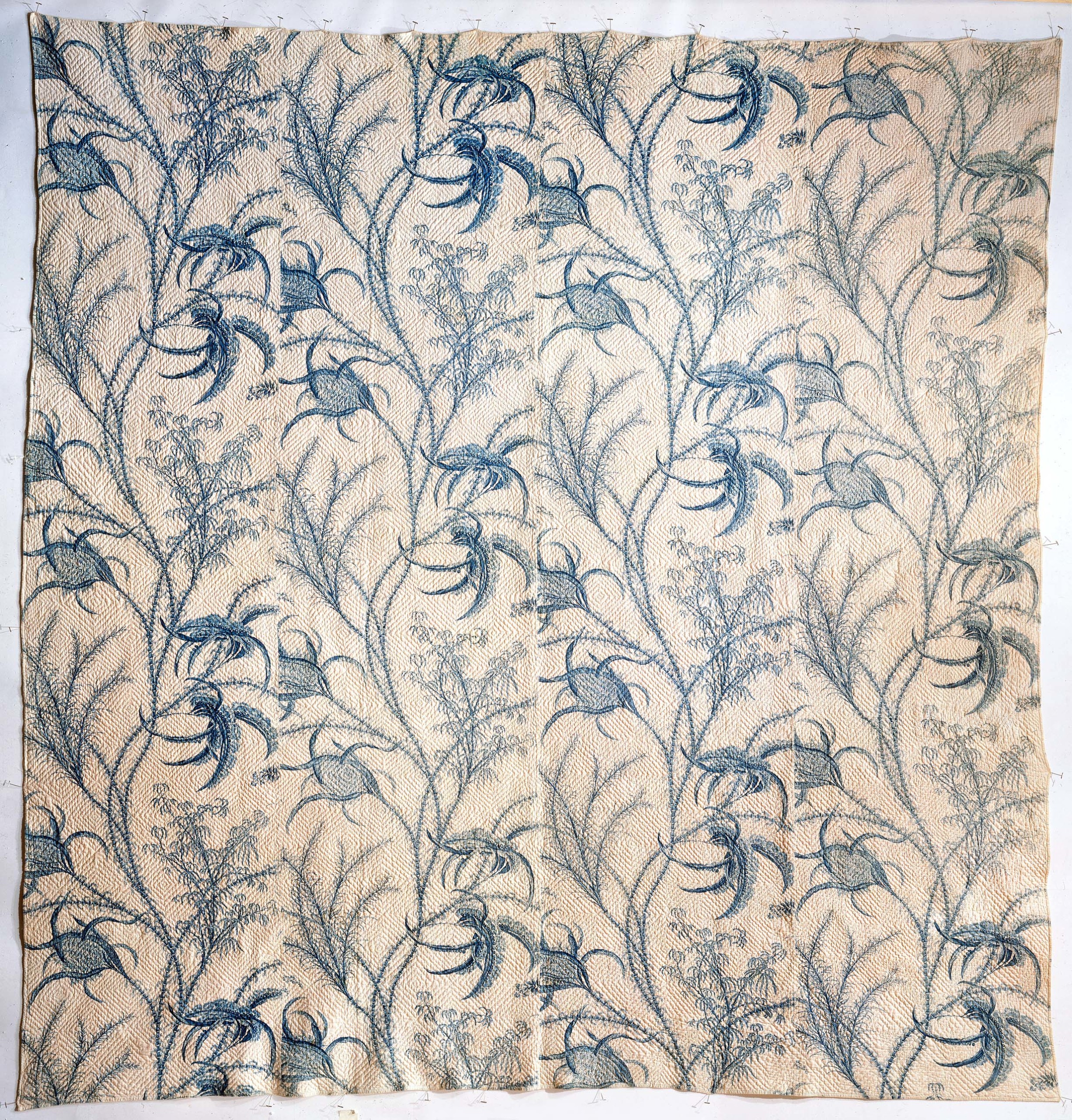

Some beloved favorites museum-goers can expect to see are a stenciled quilt, made in Conway, Mass., by sisters Olivia Denham Barnes (1807-1887) and Louisa Denham Farnham (1804-1833), that emulates theorem painting through the use of homemade stenciled designs alternating with blocks of professionally printed chintz. Another popular quilt, one made from inscribed blocks dedicated to deceased members of a church community, shows off the willow as a popular funerary motif.

Gevalt’s co-curator for the show is Austin Losada, AFAM’s Art Bridges fellow for curatorial, collections & exhibitions, who told Antiques and The Arts Weekly, “We hope the show will challenge visitors, to look beyond the eye-catching patterns and to engage more closely with the materiality of quilts. Asking, ‘Why did the quilter choose this specific printed fabric?’ and ‘How did that textile reach them to begin with?’”

“An Ecology of Quilts: The Natural History of American Textiles” will be on view from September 26 to March 1.

The American Folk Art Museum is at 2 Lincoln Square. For information, www.folkartmuseum.org or 212-595-9533