Figure 1.1 — Scrimshaw tooth by William Sizer showing nautical motifs. Photo courtesy Eldred’s.

By Rob Hoffman

It is a rare event when the identity of a previously unknown folk artist is revealed. Some folk artists — especially those working scrimshaw, — were people whose work emerged from pastime activity rather than vocation. These were ordinary people participating in their material culture in a unique but typically human manner. Folk artistry is perhaps integral human behavior harking back thousands of years to anonymous artisans who produced exquisite images of animals on the walls of European caves.

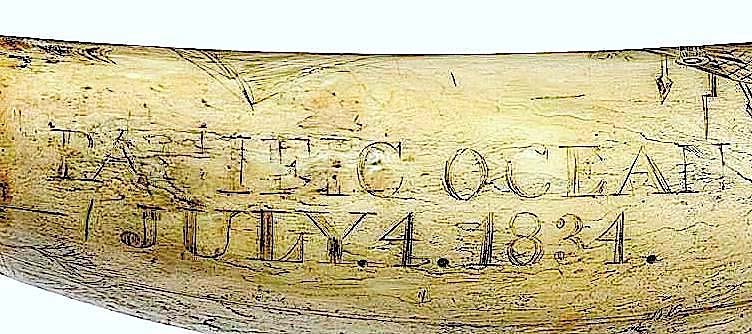

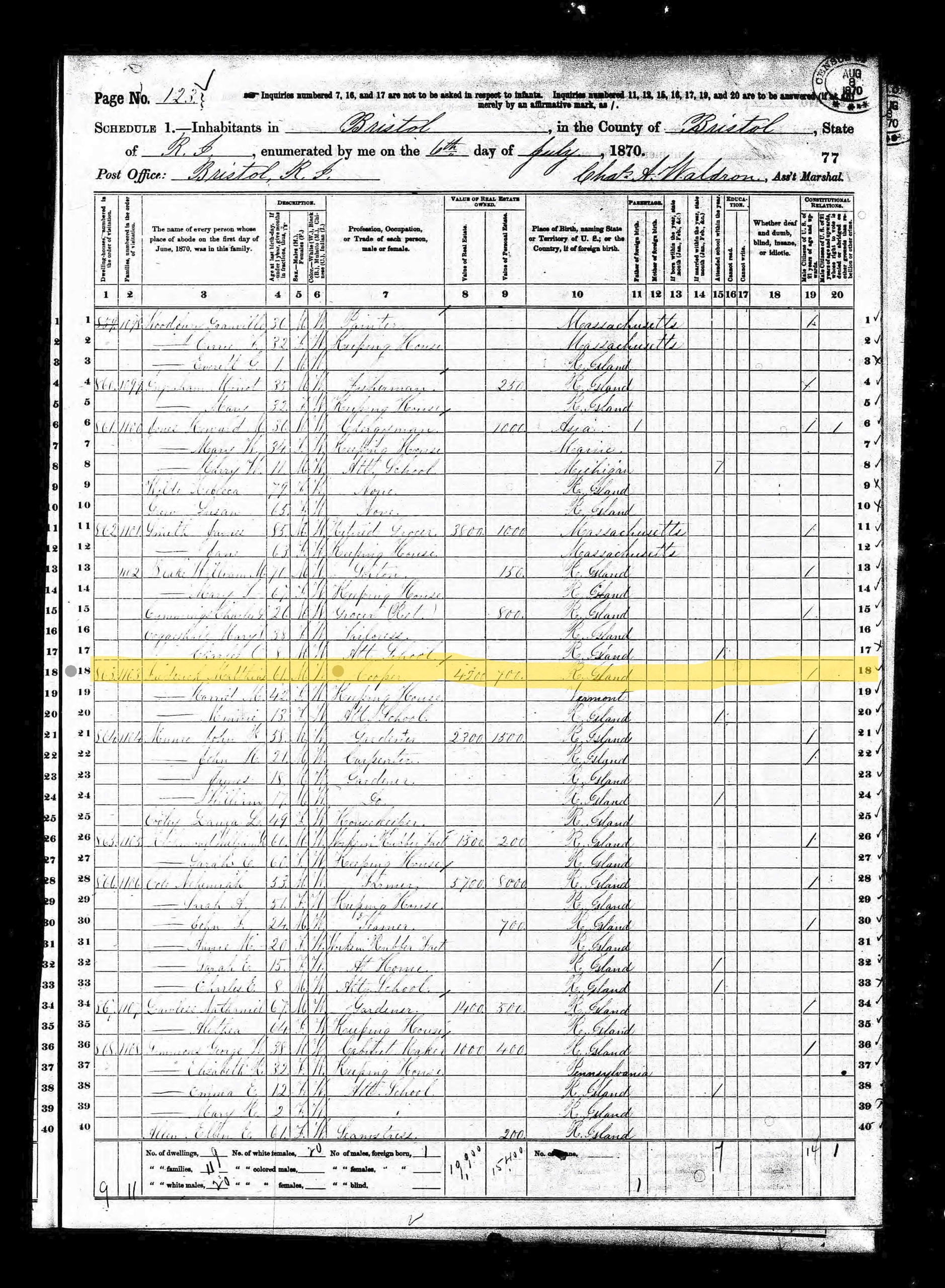

On August 13, 2020, Eldred’s auctioned a scrimshawed whale’s tooth by William Sizer; one side was inscribed “Eng. by W. Sizer”; along with various patriotic motifs, this tooth also features an uppercase block-script intaglio that read “Pacific Ocean/ July.4.1834,” (Figs. 1.1-1.3)

While Eldred’s description recognized the various incised motifs as “mostly patriotic,” no other attention was given to the reference of The Fourth of July. Perhaps this is owed to the fact that the tooth was signed by the artist — as mentioned, a rare circumstance in folk art.

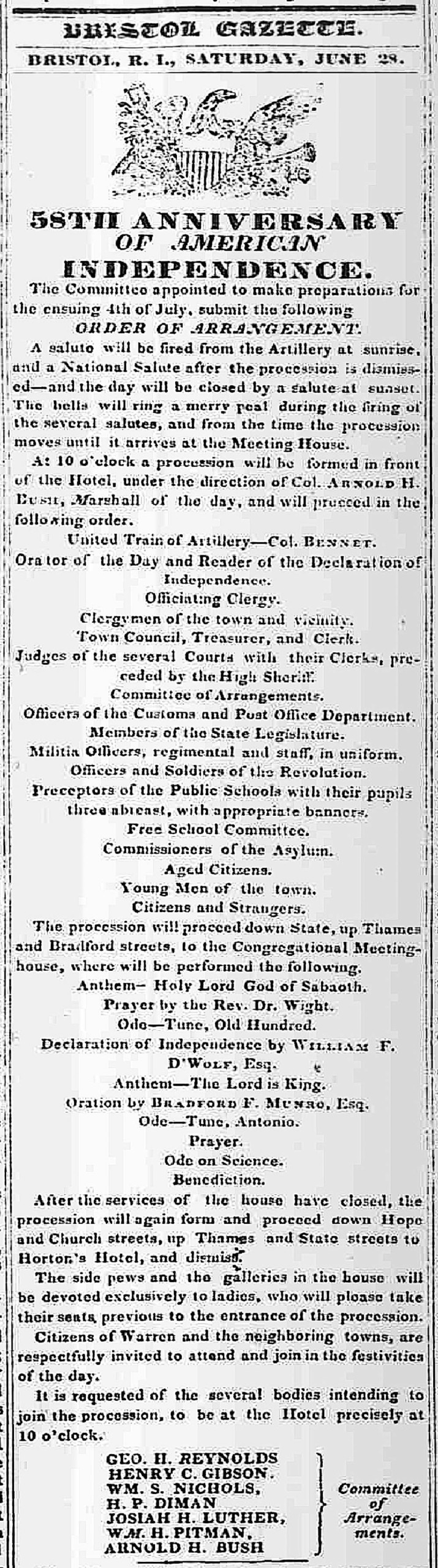

The Fourth of July is the oldest American celebration singularly identified by a date. While it might seem that 1834 is an early date for the commemorative observance of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, this holiday has deep roots, especially for the town of Bristol, R.I., the port from which William Sizer’s voyage aboard the whaleship L.C. Richmond is alleged to have originated in 1834. Bristol is reputed to be the most patriotic town in America, with Fourth of July celebrations occurring even while the Revolutionary War was still waging. Note the enclosed excerpt from the 1834 Bristol Gazette announcing holiday activities for the 58th anniversary of the Fourth of July including a parade, artillery salute and a commemorative reading of the Declaration of Independence (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 — A June 28, 1834, Bristol Gazette article announcing July 4 celebrations.

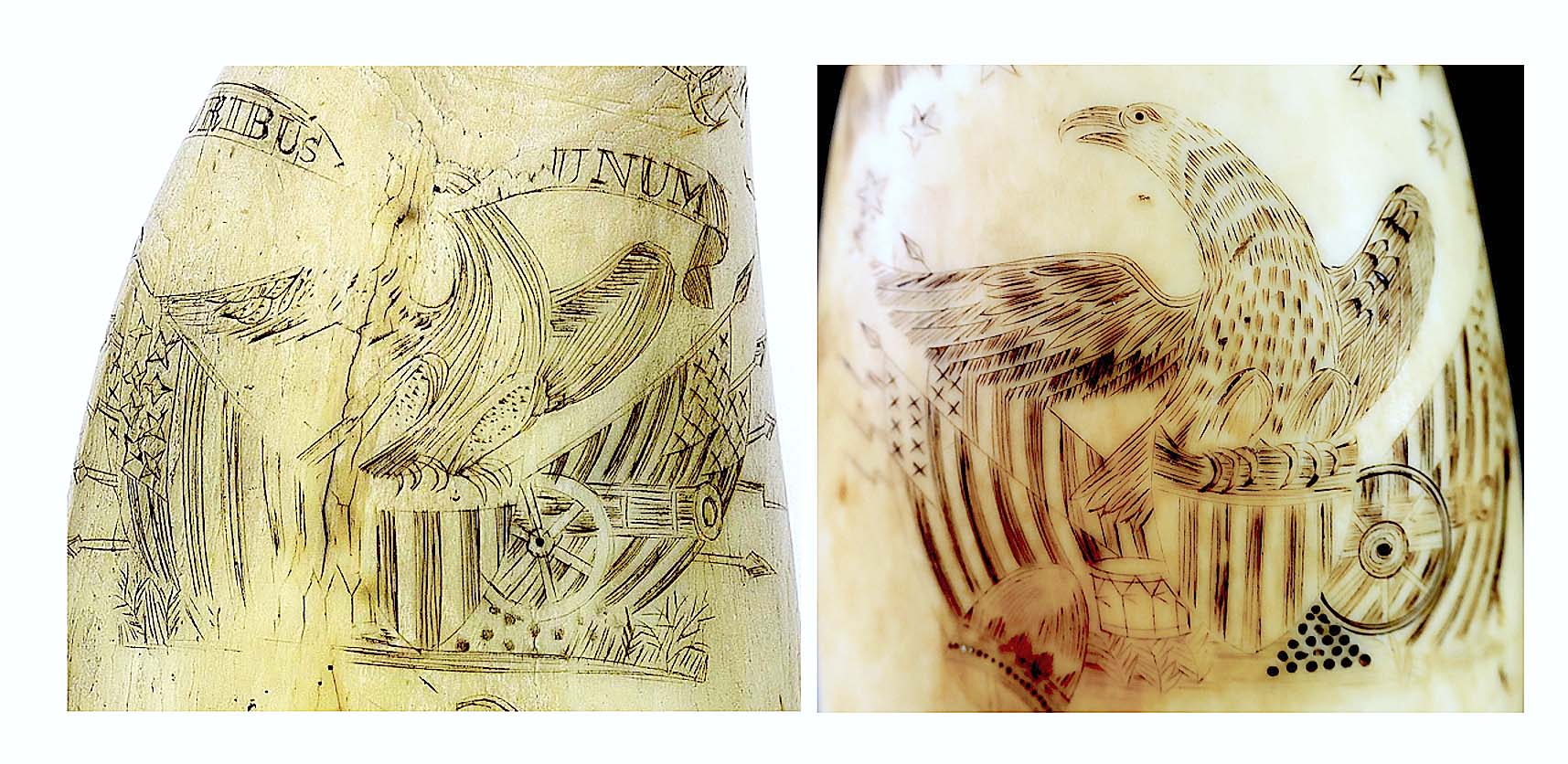

If there was any question that Sizer was evoking the celebration of American Independence with his 1834 tooth, consider another recently discovered whale tooth (Figs 3.1-3.3). Found in Florida, this tooth bears the name “M. Frederick” along with a conspicuously kindred holiday reference: “Pacific Ocean / July 4 AD 1835.”

Point by point comparison of the lettering between both the Sizer and Frederick teeth show such striking similarities it seems unlikely that both were made independently. An initial theory regarding the Frederick tooth was that it was actually made by mariner and artist, William Sizer. However, this theory loses credibility with discrete comparison of the details of the various patriotic motifs. Note, for example, variations in the rendering of the eagles, cannons and flags (Fig. 4). While side-by-side comparisons of these figures possibly support the theory of collaboration between artists, the details of the workmanship suggest execution by different hands. While lacking a ship figure, the Frederick tooth features a lavish double portrait of a young couple wearing exuberant Federal Period attire (Fig. 3.1). This is an ad hoc rendering as opposed to later Nineteenth Century sentimental engravings inspired by magazine illustrations and mastheads such as Gleason’s Weekly.

In his seminal 2012 publication on scrimshaw objects from the New Bedford Whaling museum, Ingenious Contrivances, Curiously Carved: Scrimshaw in the New Bedford Whaling Museum, Stuart Frank identified William Sizer as the “L. C. Richmond artist.” With the discovery of the Frederick tooth, it seems possible that there may have been at least two adept scrimshaw artists aboard the L.C. Richmond during its 1834-37 voyage to the Pacific. If such is the case, it is likely that both artists were cohorts who knew one another and perhaps collaborated on methods and motifs. What do we know about these two mariner-artists? Frank, in his 2013 publication, Scrimshaw and Provenance: A Third Dictionary of Scrimshaw Artists (Mystic Seaport Museum), gave biographic information for Sizer including date and place of birth, ethnicity and death. But what about Frederick?

Figure 3.1 — Scrimshaw tooth by M. Frederick showing signature, date and couple. Photo courtesy Akiba Galleries, August 9, 2022.

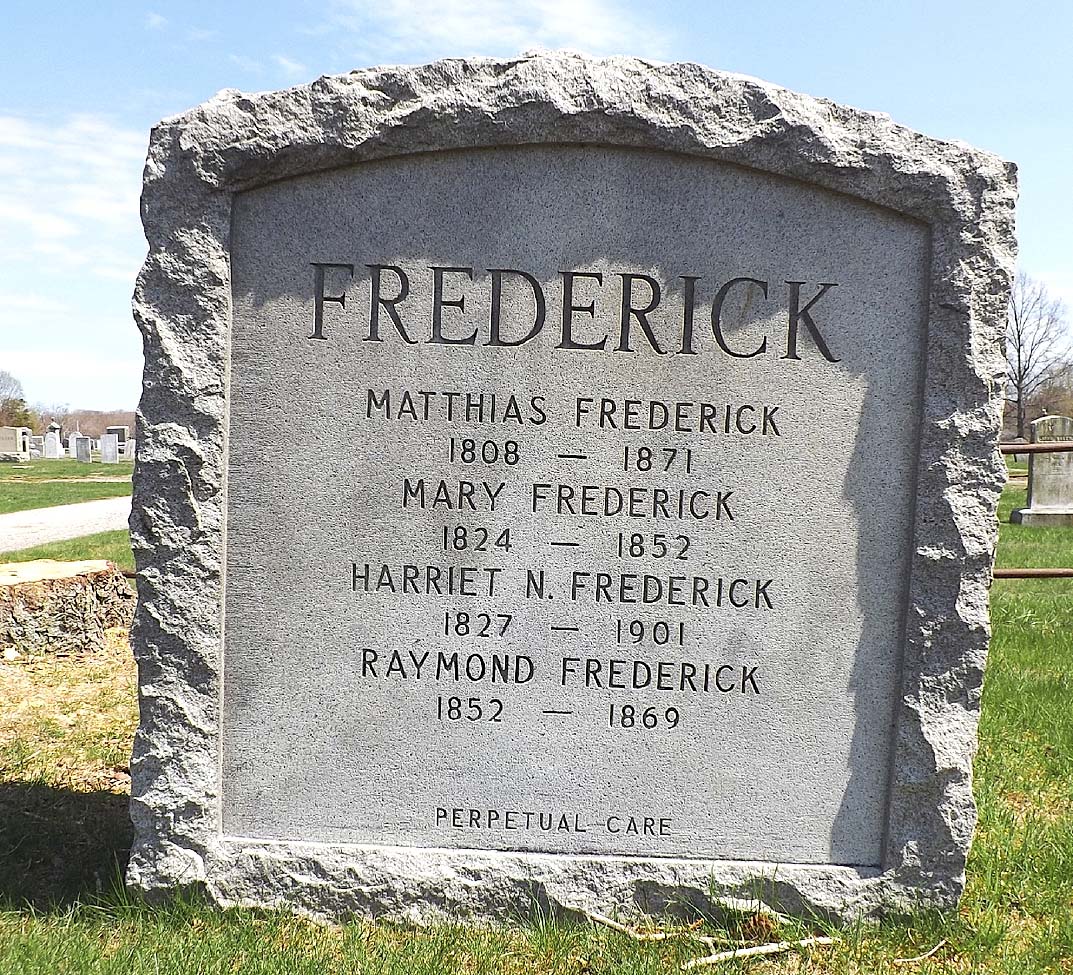

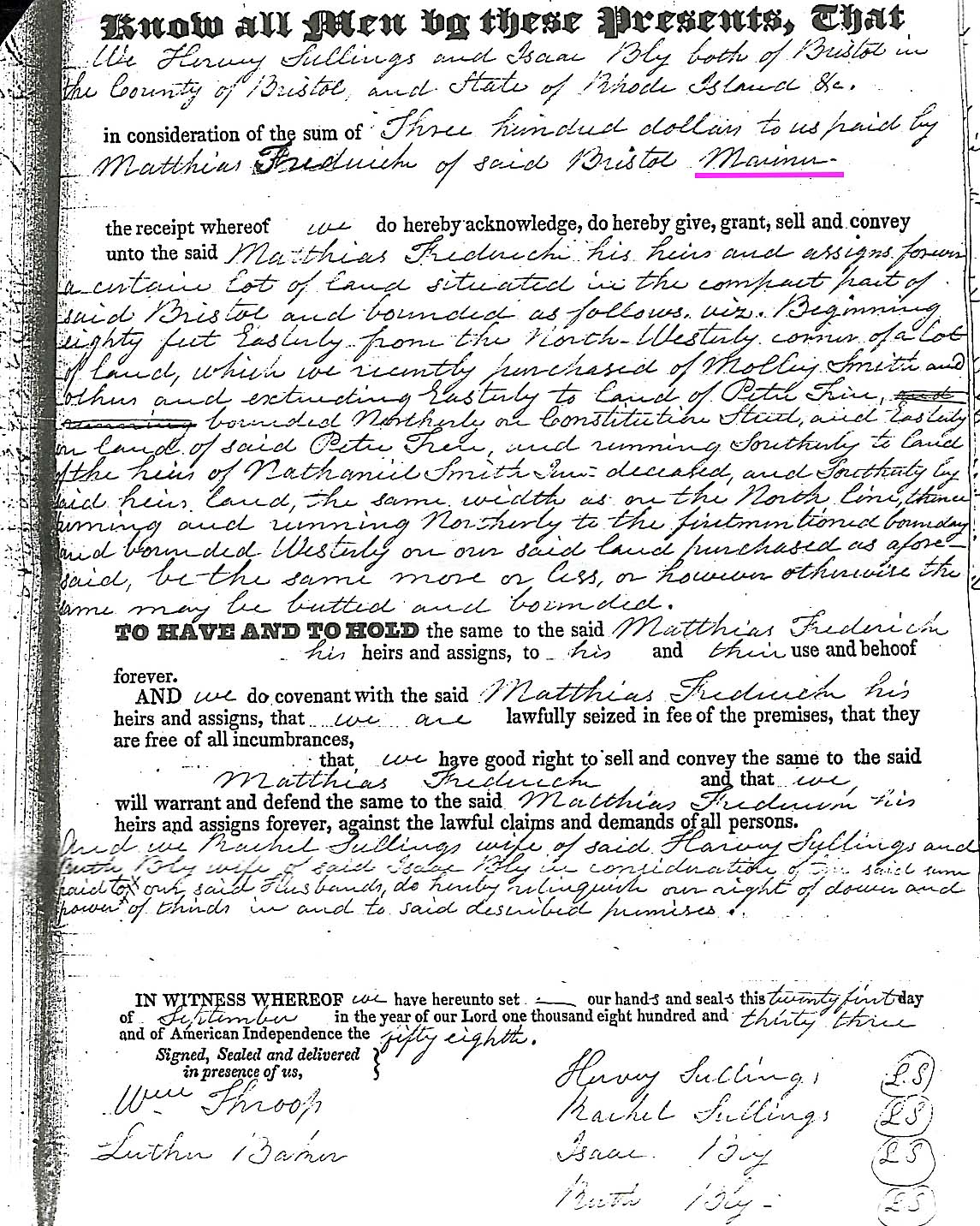

There is abundant — albeit circumstantial — evidence pointing to a Bristol, R.I., citizen named Matthias Frederick. According to historic records from Bristol, Frederick was born in 1808, spent the majority of his entire life in Bristol and was buried in 1871 in the town’s North Burial Ground (Fig. 5). Shortly before the 1834 Pacific voyage of the L.C. Richmond, Frederick purchased a plot of land on Constitution Street, a mere stone’s throw from Bristol Harbor. Note that the original 1833 hand-scripted deed identifies Matthias Frederick as a “mariner” (Fig. 6). While no evidence for a crew manifest has ever been disclosed for the 1834 voyage of the L.C. Richmond, the New Bedford Whaling Museum’s online database identifies a Matthias Frederick as a crewman aboard an 1841 voyage of a bark also from Bristol harbor, the Canton II. The New Bedford database further identifies Frederick as dark haired, light skin, standing 5 feet, 6 inches tall and a “cooper” (or barrel-maker) by trade. Later Nineteenth Century census data from Bristol also identifies Frederick’s occupation as cooper. (Fig. 7). The ability to craft wooden barrels would have been a valued skill aboard a Nineteenth Century whaling vessel whose ultimate objective was to procure and transport whale oil. We might also infer that someone adept at barrel-making might also be skillful in tool use — a valuable asset for someone aspiring to scrimshaw manufacture.

Consider, as earlier mentioned, that aside from their surviving works of art, American maritime scrimshaw artists were pretty much ordinary citizens for whom scrimshanding was an amateur pursuit. Bristol historic records portray Matthias Frederick as a mariner in his younger days but a cooper by trade thereafter. While he purchased property just prior to the 1834 voyage of the L.C. Richmond, Bristol historic records show that more than a decade elapsed before he developed his property by building a Greek Revival-style house, which still stands at lot 73 on the south side of Constitution Street. (Fig. 8).

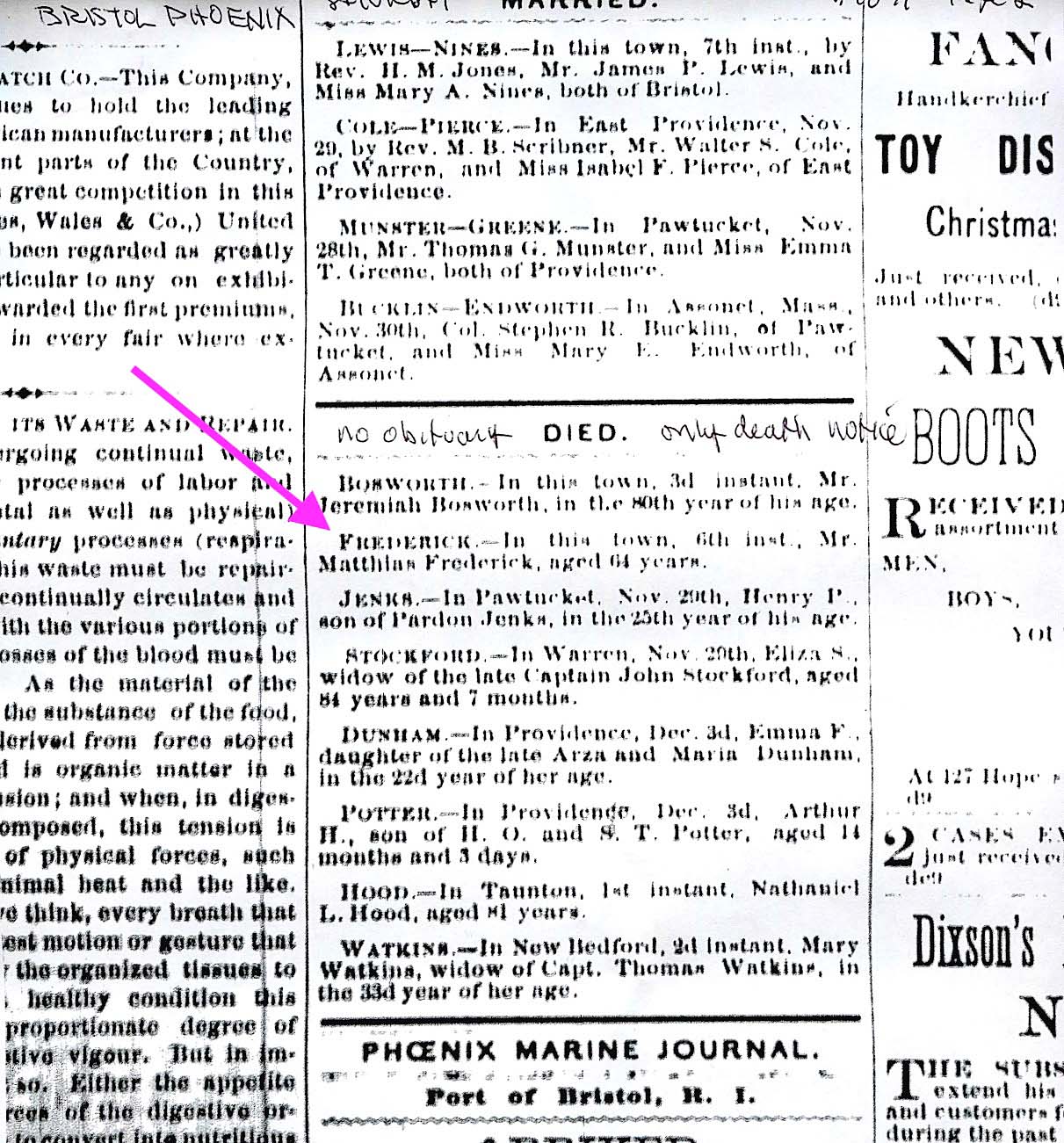

Figure 9 — M. Frederick’s death announcement, Bristol Phoenix, undated. Photo courtesy of the Bristol Historic Society.

The ultimate historic document for Matthias Frederick is an 1871 Bristol newspaper obituary noting his passing at age 64 (Fig. 9). An additional grim reference identified the cause of death as suicide via suffocation with no additional explanation noted. As stated, the assertion that the M. Frederick Fourth of July tooth was crafted by Matthias Frederick of Bristol, R.I., is circumstantial but abundant and compelling.

Returning to the issue of the Fourth of July inferences regarding both the Frederick and Sizer whale teeth, consider the logistical implications of a Nineteenth Century whaling expedition that commenced in Bristol, R.I., bound for the Pacific Ocean. Long before the advent of the Panama Canal, the only maritime route from New England to the Pacific Ocean was a months-long voyage along the eastern coast of North and South America followed by a treacherous and tangled passage through the Strait of Magellan. Whaling voyages are well documented for subjecting their human cargo to long periods of desolation, discomfort and malaise, as noted by Nina Hellman and Norman J. Brouwer in A Mariner’s Fancy: The Whaleman’s Art Of Scrimshaw 1992. The maiden voyage of the L.C. Richmond persevered from 1834 through 1837. It is not difficult to imagine these New England crewmen as de facto prisoners confined by a 200-foot-long floating dungeon on a journey spanning not one but two or three midsummer holidays thousands of miles from loved ones and home.

A long whaling voyage is an exercise in coping with the malaise of tedium and lethargy. The product of the scrimshander is a harvest sewn by ennui. To quote Norman Flayderman in Scrimshaw and Scrimshanders: Whales and the Whalemen (1972) “scrimshaw rescued the whaleman from his despondency.” Perhaps for Matthias Frederick, the Fourth of July was an important euphoric memory of blissful youth and better times. Here lies the true backstory for pretty much all American scrimshaw objects. It is an allegory of ordinary humans performing exceptional enterprises under extraordinary circumstances.

Figure 3.3 — Scrimshaw tooth by M. Frederick showing patriotic motifs. Akiba Galleries photo.

Lastly, weigh the implications given the circumstances in which the identity of a previously anonymous non-academic artist is incidentally disclosed. Such is the nature of science and art amid continuously flowering evidence and information. Consider an analogue from the realm of American folk-art portraiture. Prior to finding an 1836 portrait of a preacher’s wife signed by a previously unknown artist named Milton Hopkins, similar works were habitually misattributed to artists such as J. Bradley or Hopkin’s disciple, Noah North. As discussed in Face to Face: M.W. Hopkins & Noah North (Jacquely Oak, Grant Romer, Mary Black, David Tatham and William Siles, 1989), when a signed Hopkins portrait was discovered, this “Rosetta stone” prompted a reevaluation of the entire body of collateral work.

Now consider two additional scrimshaw examples, (Figs 10 and 11). Both were attributed to William Sizer by Sotheby’s in 2016 and Osona Auction in 2017. Under the circumstances, justification of these attributions is perfectly understandable. But what if those attributions were now compared and reevaluated in light of the discovery of the Frederick tooth? (Fig. 11.1)

It is outside the scope of this article to attempt systematic re-evaluation of any or all scrimshaw specimens formerly attributed to William Sizer, the so-called “L. C. Richmond artist.” However, if the recently discovered M. Frederick tooth discussed herein is confirmed to have been produced aboard the L.C. Richmond by Matthias Frederick, a professional cooper from Bristol, R.I., revision of previous criteria for evaluation and attribution of a significant school of scrimshaw engraving is perhaps warranted.

Author’s note: The author is indebted to the canny and diligent assistance of the following people and institutions: Rei Battcher, Bristol Historical Preservation Society; Rogers Free Library, Bristol, R.I.; Rafael Osona Auction, Nantucket, Mass.; Josh Eldred & William Bourne, Eldred’s, East Dennis, Mass.

[Editor’s note: Rob Hoffman is an antiques dealer and scrimshaw scholar based in Florissant, Mo.]