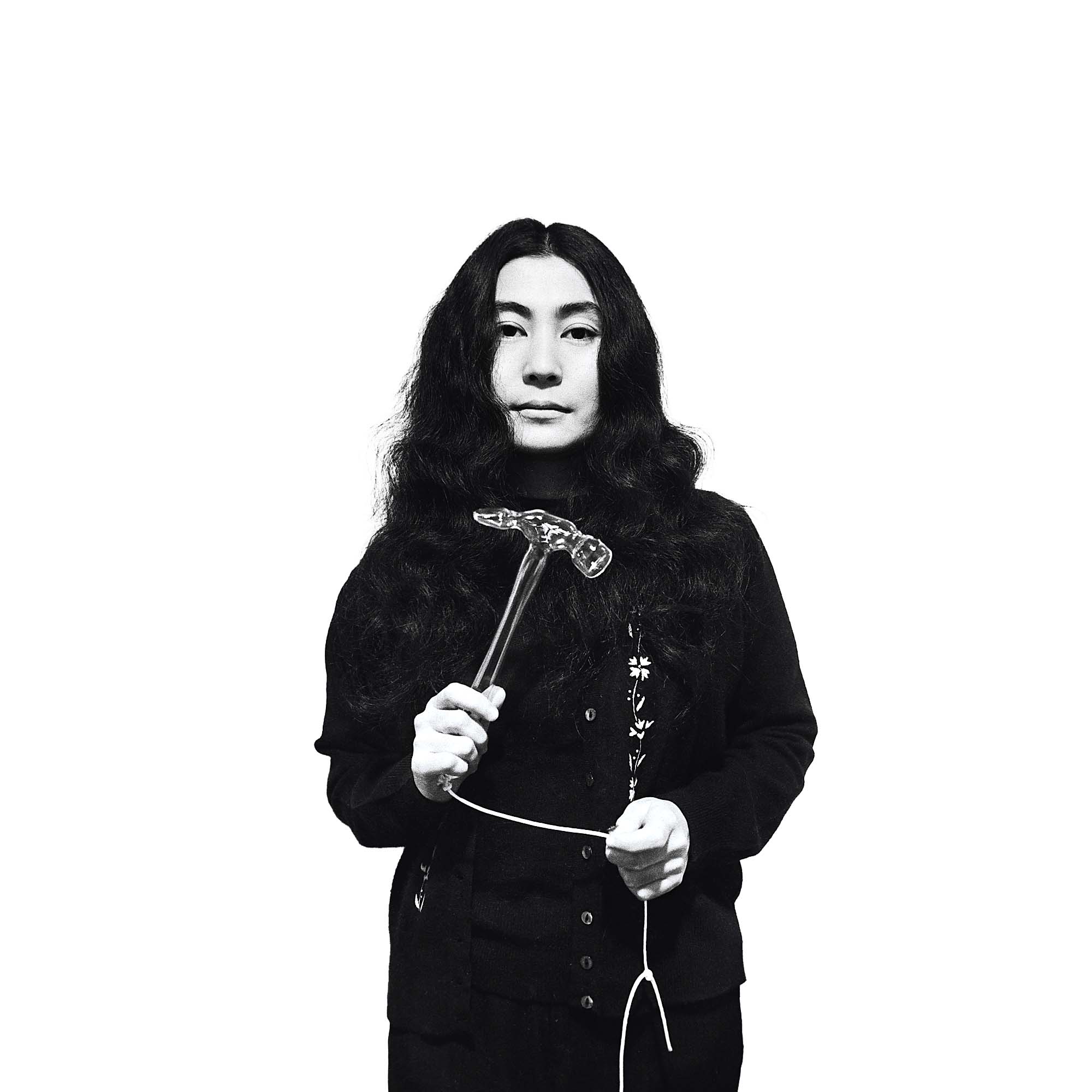

Yoko Ono with “Glass Hammer,” 1967. © Yoko Ono. Photo by and © Clay Perry.

By Laura Layfer

CHICAGO — “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” is now on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago, originally its first and only destination in the United States (a recent announcement notes it will travel next year to The Broad in Los Angeles) following a premiere in London at the Tate Modern. The connection the artist has to the Windy City is surprisingly strong and marks another American-based first for Ono — that of a permanent public artwork. Installed in 2016, “Sky Landing” is situated in Jackson Park, near the future site of the Obama Presidential Center. The sculpture features large-scale lotus petals made of metal that look to what is above as much as the significance of what is below. The placement is on the same grounds where the Japanese Pavilion was housed during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. For Ono, an artist, poet, musician and activist, her creative practice seems to have always been strongly rooted in both tradition and transience.

Born in Japan in 1933, she was raised in Tokyo, where her family was in the banking industry. In the 1950s, they moved to New York and she pursued music studies at Sarah Lawrence College. There, she began to experiment with songs and words, and soon involved herself in the avant-garde art scene. By the 1960s, she was quickly becoming an instrumental figure in Fluxus, an international art movement focused on performance and conceptual art. When she started to explore film and other mixed media, a new instructional component emerged that orchestrated how viewers could and should engage with works.

Installation view, “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind,” MCA Chicago, October 18, 2025-February 22, 2026. Photo: Bob (Robert Chase Heishman).

“This entire show is meant to be in community and an immersive experience that highlights the full spectrum of Ono’s life and career,” says MCA curatorial assistant Korina Hernandez, who was part of the curatorial team alongside Jamillah James, the Manilow senior curator, and in collaboration with Yoko Ono’s Studio One, based in New York City. “Ono was a major player in Fluxus, and too often she is only referenced in relation to her marriage to John Lennon rather than her art alone,” notes Hernandez. By offering a chronological and cross-continental representation in this retrospective (Tokyo, New York and London), Hernandez hopes viewers will recognize the breadth and depth of the artist. The more than 200 works on display throughout the galleries trace the sounds, semantics and stages in Ono’s journey.

“Wish Trees” welcomes visitors in the main atrium of the galleries with a request to write down a hope or a dream on the provided paper. Then, participants can take a string and hang their notes from the branches on small trees in the installation. The difference of each script reveals much of what is the same between humanity, as people write about the possibility of a cure for cancer and visions of health and love for their families.

In 1964, Ono published Grapefruit, a manuscript of instructional, often poetic, writings. These directives went on to become some of her most groundbreaking productions and continue to be shown in multiple iterations. For example, “Cut Piece,” originally debuted in the 60s in Kyoto, and later, as the video shown at the MCA documents, in New York City at Carnegie Hall. In the latter performance, Ono sits silently as audience members approach her to use scissors and tear off fabric from her clothing. The provocation of the scene is immediately apparent as is the unease of watching this slow and intimate reveal.

Author and her daughter, Jane, deciding where to add their work to ‘“Mend Piece. ” Photo by the author.

Similarly, “Mend Piece” brings light to what has been lost or fallen and the process of healing and reparation. Here, shards of pottery are scattered over tables where visitors can access tape, glue and string to recycle these random pieces into objects of their own design. The surrounding white walls are lined with shelves for displaying these “second chances” of sorts and give participants insight into the value of imagining new paths of possibilities as well as the vulnerability that comes with sharing one’s vision, as artists do, for public consumption. Additionally, this is an homage to the Japanese technique of kintsugi, where ceramics are repaired with a lacquer and metal mix that remain visible to signal the beauty in a second chance for a ware.

In another example from Grapefruit comes “Painting to Shake Hands (painting for cowards),” a blank canvas with a drilled central hole that invites one to place a hand through the opening and reach out to connect with another on the opposite side. No words or conversation, blocked from face-to-face, it is a way to unify through touch rather than words or expression. In a different gallery, “White Chess Set” brings another outlet to bridge gaps. Here, Ono’s installation of an all-white game board is accompanied by her prescription to “Play it for as long as you can remember/ who is your opponent and/ who is your own self.” Several game tables are staged in the galleries as enthusiasts of all ages are invited to join, friends or strangers, linked in brief moments.

Yoko Ono with “Half-A-Room,” 1967. © Yoko Ono. Photo by and © Clay Perry.

“Half-A-Room” was initially shown in London in 1967, and mimics the interior of a home with a bookshelf, a painting on the wall, a chair and a single shoe, amongst other items that are each shown either cut or as one of a pair. The accompanying museum label mentions Ono’s commentary on the piece. “Molecules are always at the verge of half disappearing and half emerging… Somebody said I should put half-a-person in the show. But we are halves already.” The message is similar in “Helmets (Pieces of Sky)” where, dangling from the ceiling in a bucket-like fashion, onetime WWII head coverings are filled with puzzle pieces of blue and white color variants that make up the sky. Patrons are encouraged to take one home and find the ways it can fit within their personal perspective on war, peace and the greater universe above.

There is a music gallery with beanbags for lounging as Ono’s albums play through speakers. In 1981, she was nominated for a Grammy for “Walking on Thin Ice.” Released that year, it was the final work she completed with her late husband — recorded a year earlier, just before the Beatles legend was shot — and one that had been inspired by a frozen Lake Michigan seen during their visit to Chicago back in the 1970s.

Visitors explore Yoko Ono’s “Add Colour (Refugee Boat),” 1960/2016, in “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind,” Tate Modern, London, February 15-September 1, 2024. © Yoko Ono. Photo © Oliver Cowling, courtesy of Tate.

Themes of permanence, or the lack thereof, have long surfaced in Ono’s professional endeavors. While “Apple” elevates the status of a green fruit by placing it in plexiglass where decay is inevitable, “Add Colour (Refugee boat)” is a reminder of the difficult plight of migration and immigration, and the power of humanity when working as a collective entity. The latter, in a final space of the show, starts as an all-white room with a vessel at the center, and is a work conceived by Ono back in 1960. At the MCA today, blue pens offer an opportunity for visitors to help complete it by writing their ideals for a better future anywhere and everywhere. In this effort, the sea of blue messages can suggestively wash away the hardships and pain endured both now and then by so many, including the artist’s own dark memories from her youth.

At 92 years old, Ono is still asking all of us to join her and simply imagine.

“Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, at 223 East Chicago Avenue, until February 22. It will then go up at the Broad, May 22-October 11.

For information, 312-280-2660 or www.mcachicago.org.