“Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War),” by Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989), 1936, oil on canvas, 39-5/16 by 39⅜ inches. Philadelphia Art Museum: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950.

By Andrea Valluzzo

PHILADELPHIA — As post-Impressionism gave way at the turn of the Twentieth Century to modern and avant-garde art styles, including Expressionism and Cubism, art became increasingly individualistic.

Rival European poets André Breton and Yvon Goll, each part of their own group of Surrealists, helped define Surrealism in late 1924 with their separate publications of a Surrealism manifesto. Breton focused on Surrealism in the arts as harnessing psychic automatism in a pure state to allow for expressionism without need of written text or conscious thought. Operating in a surreal state was said to allow dreams to blend with reality, which was necessary to reclaiming a childlike sense of imagination that adults tended to discard, he wrote. The Surrealist movement, which mostly adopted Breton’s definition, kicked off in earnest in 1925.

The Philadelphia Art Museum is one of five museums around the world hosting an exhibition to celebrate Surrealism’s centennial and its legacy and effect on art today. While a core group of artworks traveled from museum to museum for this exhibition, each institution had a different focus, and some featured additional artworks not seen in other venues. Organized by the Centre Pompidou in Paris, “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100” is now in Philadelphia, at its final venue, through February 16. Earlier stops were in Paris, Hambourg, Madrid and Brussels.

“Aphrodisiac Telephone” by Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989), 1938, plastic and metal, 8¼ by 12¼ by 6½ inches. Lent by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, The William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

In Philadelphia, the metamorphic exhibition showcases about 180 artworks, including sculptures, paintings, films, prints/drawings, photographs and found object constructions.

The exhibition begins with the early days of Surrealist art in the 1920s, a period of great experimentation, with the found-object constructions of Man Ray, Max Ernst’s genre-bending collages and fantastical paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. It moves through the decades and motifs from hallucinatory landscapes and creatures to references to mythology, and how artists reacted to the world around them, especially during World War II.

“There is a core of works that move from museum to museum on this tour, and there are great works from us that traveled from museum to museum,” said Matthew Affron, the museum’s Muriel and Philip Berman curator of Modern Art. “Each curator and institution was given a free hand to tell the story of Surrealism in a way that made sense for either the place or the collections where they are working, so each version is quite different. I think maybe only about 20 percent of the checklist in Philadelphia overlaps with Paris.”

Unique to Philadelphia is a special focus on the Surrealists who came to Mexico and New York at the start of World War II. Largely a museum of gifts, the museum is particularly rich in this genre.

“The Soothsayer’s Recompense” by Giorgio de Chirico (Italian, born Greece, 1888-1978), 1913, oil on canvas, 53⅜ by 70⅞ inches. Philadelphia Art Museum: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950.

Among artworks not in the Paris show but on view here is De Chirico’s 1913 oil on canvas painting “The Soothsayer’s Recompense,” which symbolizes the sleeping Greek princess, Ariadne, pictured in a state of loneliness. Mythology is a throughline in the exhibition, and this painting is a fitting example. According to the lore, Ariadne was discarded by her lover Theseus after helping him escape from the minotaur’s labyrinth. De Chirico’s use of perspective serves to affect how viewers interpret the urban piazza shown.

“Surrealist art has been a focus of our museum since receiving the generous gifts of the Louise and Walter Arensberg collection in 1950 and the bequest of the Albert E. Gallatin collection in 1952,” said Affron. The museum’s permanent collection includes works by Marcel Duchamp and key artists associated with Surrealism, such as de Chirico, Joan Miró, Magritte, Jean Arp, Dalí and Dorothea Tanning.

Gallatin opened the Gallery of Living Art in 1927 in New York City, a full two years before the Museum of Modern Art came to be. It was the first public collection dedicated to modern art in the United States. The Arensbergs were first renowned New York-based art collectors, later in California, and the primary patrons of Duchamp.

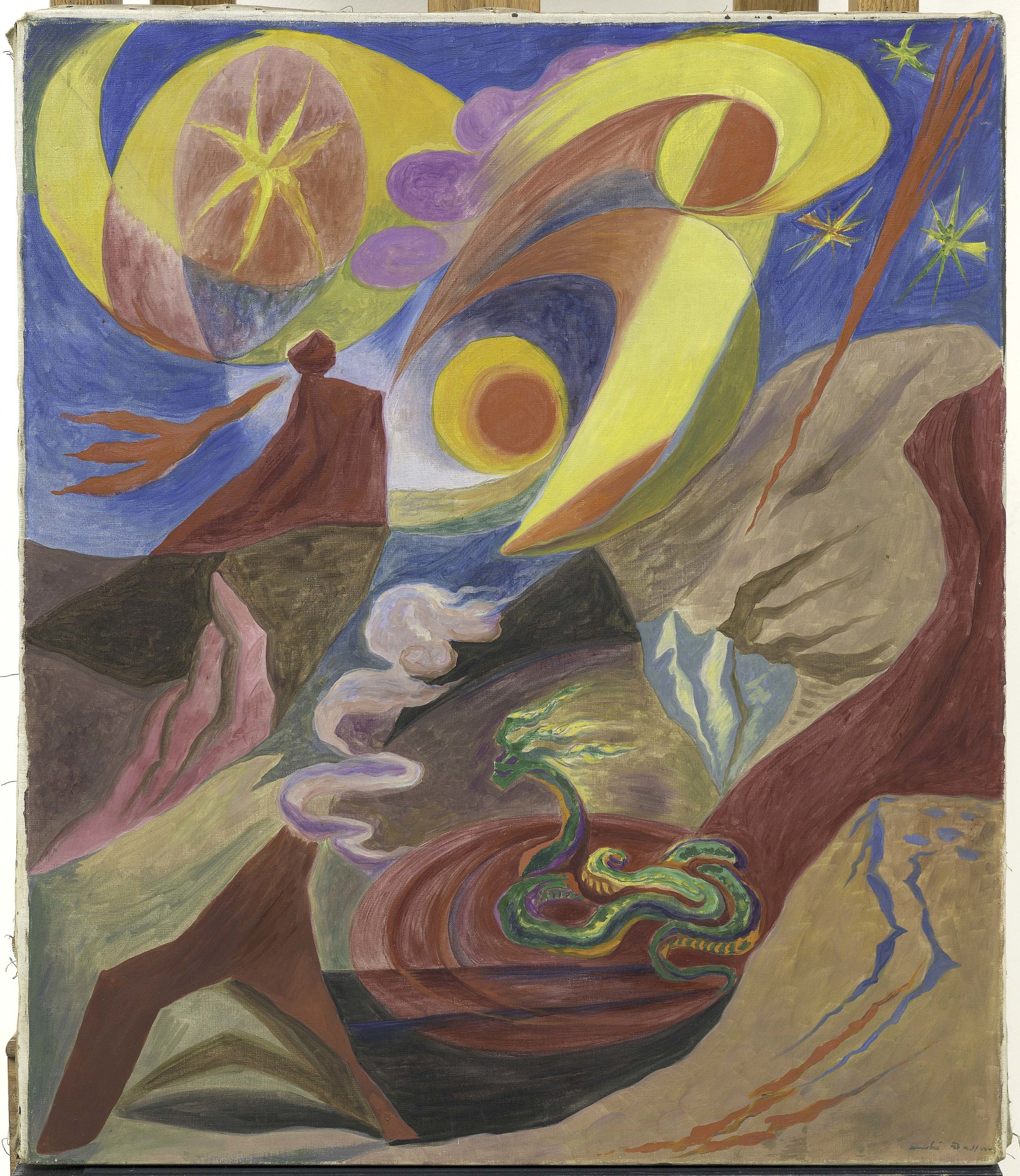

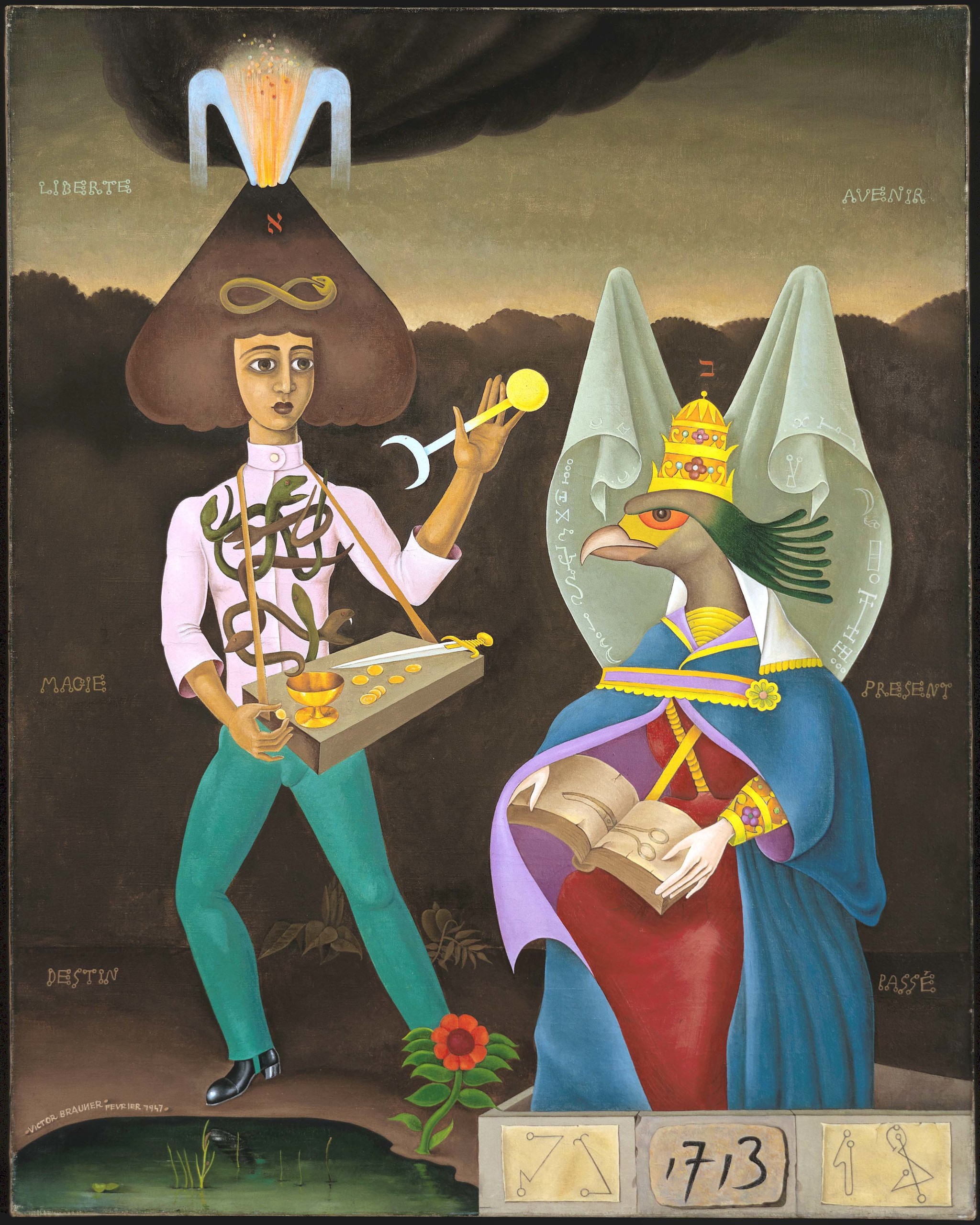

“The Lovers (Messengers of the Number), February” by Victor Brauner (Romanian, 1903-1966), 1947, oil on canvas, 36¼ by 28¾ inches. Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris: Bequest of Madame Jacqueline Victor Brauner, 1986.

“In constructing the checklist for our version of the exhibition — which, like all the versions that traveled, is quite different from the others — I really wanted people to understand that there is no such thing as a single Surrealist style or single Surrealist way of working or primary Surrealist medium,” Affron said, explaining that this tenet is one of the most remarkable features of Surrealist art. He organized the exhibition to be broad, both chronologically and thematically, to emphasize that diversity.

Besides the availability of the museum’s trove of Surrealist art, Affron said a reason why this subject makes sense in Philadelphia now is that Surrealism has all these different sorts of signature techniques and ways of working, like collage, the exquisite corpse or double split self. “If you look at art today, you see those same ways of working being used in similar ways by artists. You can define its history (Surrealism) this way or that way, but the underlying energy and spirit of Surrealists’ methods is very exciting for today’s audiences,” he said.

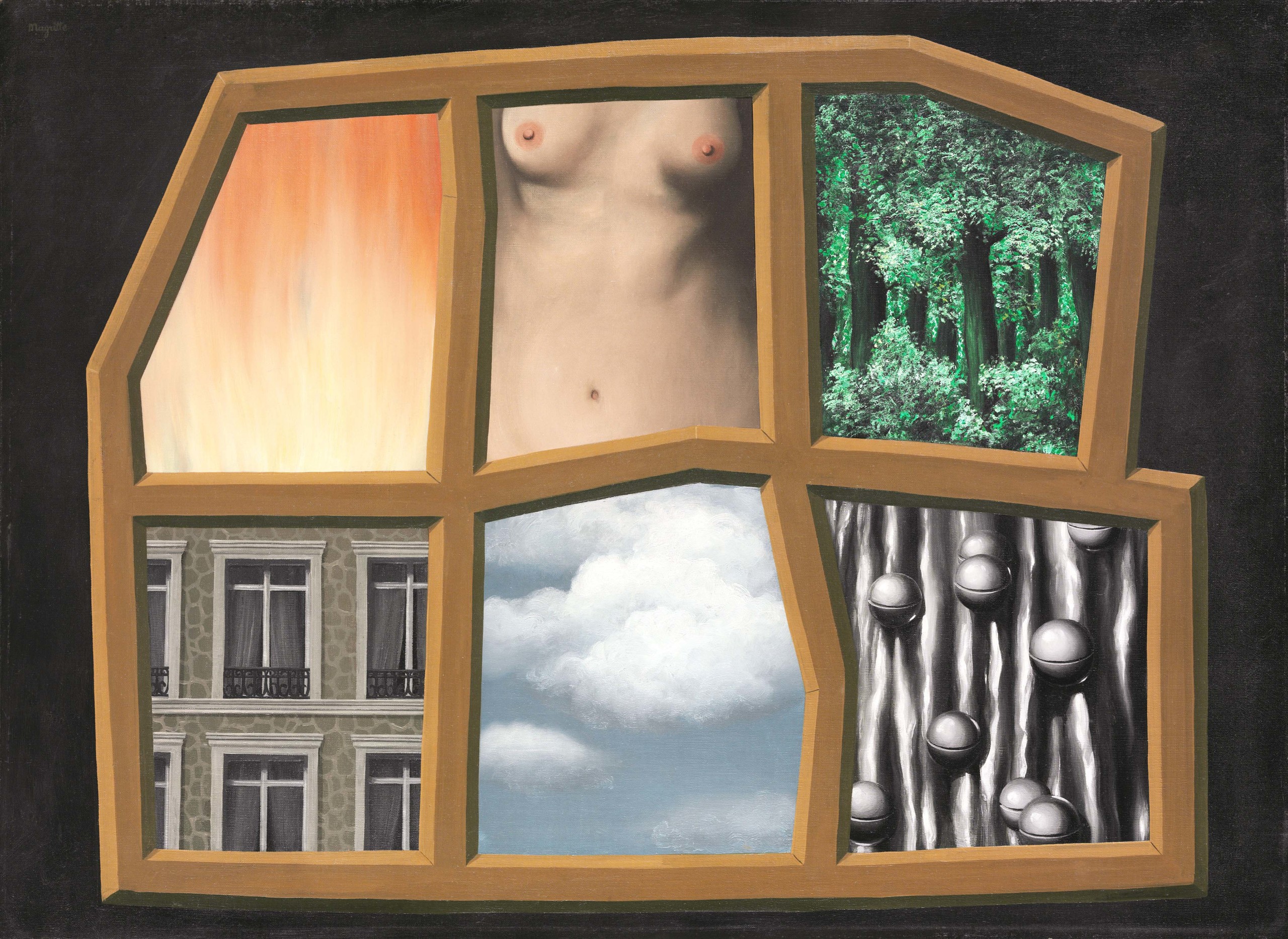

Among paintings likely to captivate viewers is Magritte’s “The Six Elements,” a 1929 painting that references universal elements like air, fire, water and earth but also includes other seemingly unrelated images, such as a female torso and bells. Perhaps Magritte is challenging viewers to look at how they perceive reality and explore the relationship between the rational and irrational.

“The Six Elements” by René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967), 1929, oil on canvas, 28¾ by 39-5/16 inches. Philadelphia Art Museum: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950.

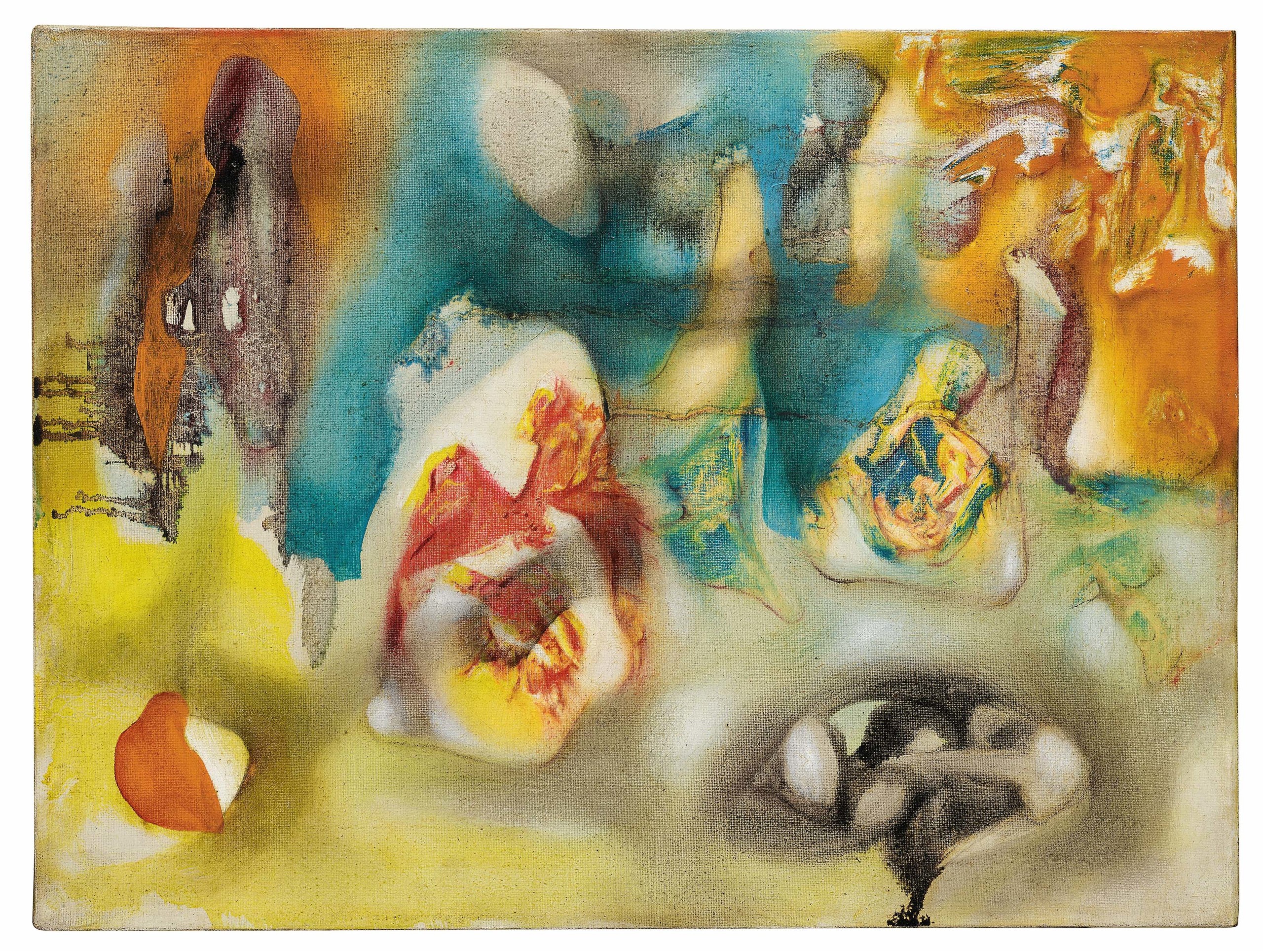

Dalí, famous for his Surrealist works like “The Persistence of Memory,” which juxtaposes a melting clock against the precisely-rendered cliffs of Catalonia, is represented in this show with the allegorical “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War).” He painted this while living in exile in Paris in 1936 as his homeland waged war with right-wing forces. The painting is not shy about depicting the carnage of war in grisly detail, with body parts strewn about the canvas. The bizarre sprinkling of beans on the ground is likely to represent the wild direction unconscious thoughts can take.

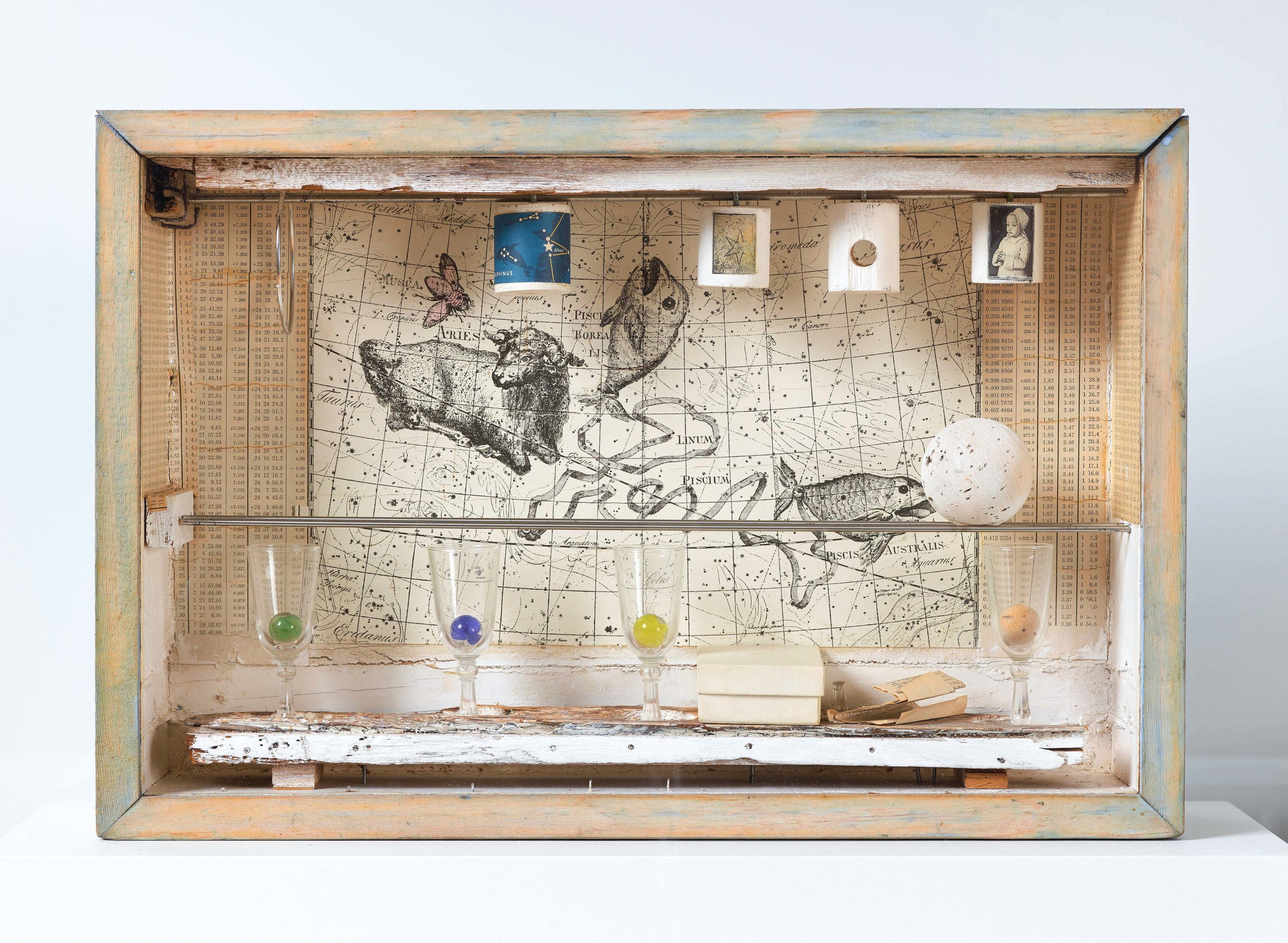

Besides paintings, there will be a great variety of multidimensional works, such as Dalí’s “Aphrodisiac Telephone,” a 1938 artwork made of plastic and metal imagining a telephone in the form of a lobster. The idea of this sculpture originated with a drawing Dalí did a few years earlier for a magazine that asked for his thoughts on American culture. One drawing showed a man reaching for the phone handset but picking up a lobster instead. Joseph Cornell is famous for his poetic dioramas and included here is one of his untitled box constructions, made circa 1958. Featured in it are various found objects, glasses and paper, mostly showing animals, that together create a mini universe.

Affron was deliberate in choosing a broad range of artworks for the exhibition. “I thought a good way to convey that essential diversity of Surrealist art was to be pretty consistent in mixing it up with the media, sizes and types of works in every section of the show,” he said.

“Icon” by Remedios Varo (Spanish, 1908-1963), 1945, oil with mother-of-pearl and gold leaf inlays on wood. 23⅝ by 15-7/16 by 2⅛ inches, closed; 23⅝ by 27-9/16 by 2⅛ inches, open. Colección Malba. Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 1997.

He hopes viewers come away with a clearer understanding of the development of Surrealism from the beginning years up through the 1950s and its continuing influence on artists today.

“It’s an ambitious and large-scale exhibition with great loans from museums and private collections in Europe and in North America and Latin America, with an exciting mixture of works in different mediums,” he said. “I think it will demonstrate the different ways in which Surrealist expression came forward in painting, drawing sculpture, found object pieces and films, and it will celebrate the anniversary of the Surrealist manifesto.”

The Philadelphia Art Museum is at 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For information, 215-763-8100 or www.philamuseum.org.