The field may look sparse, but the back field’s tents were stuffed with shoppers dodging showers until early afternoon.

Review & Onsite Photos by Z.G. Burnett

BROOKFIELD, MASS. — The Walker Homestead has hosted more than three centuries of events and is celebrating 15 years of biannual Antiques & Primitive Goods shows. Its latest took place on June 14, when Massachusetts broke its record of 13 consecutive rainy Saturdays, topping 12 in 1970 and 1943. Nonetheless, the Walker Homestead’s shows feel cozy whatever the weather, with its community members chatting happily, homemade baked goods and lunch foods available and a newer innovation of some dealers filling their tents with scented candles or incense aromas. Despite gate numbers being slightly dented, the majority of dealers reported strong sales, as those who did brave the weather were especially enthusiastic shoppers.

The Walker Homestead hosts more than 40 vendors and stands out among other shows in the area for offering both antique and reproduction furniture, decor and art. Customers with full bags and rolling carts were spotted returning to their vehicles in the parking lot field within an hour of the show’s opening, and then many went for a second or third round. One woman was overheard to have gone back and forth four times by early afternoon. Knowing their buyers well, Walker Homestead has a healthy team of porters to usher larger goods out of dealers’ tents. Many of these were picked clean of smalls by the day’s end, as were makers with easily transportable objects like garden trellises and hand-hooked rugs.

Tucked away near the center of Massachusetts, the Walker Homestead’s dealers are mostly located in southern New England and New York state. Country homes in this area often yield unexpected treasures that have otherwise sat untouched for generations. Such was the case with a boldly painted hutch from Stacey Dailey and Patrick Wyss of The Primitive House, Earlville, N.Y. Covered with original black paint on the exterior surface and bright turquoise on the backboard and interior cabinet, the hutch’s upper sideboards showed a curious wavy pattern that supported the extended shelves. These also showed central convex extrusions, minus one that was broken off. “We just got it from a house in southern New York,” shared Wyss. The hutch was in the owner’s family since the early Nineteenth Century when their house was built, and “she was not into antiques.” All the better for its next owner.

Brought from the house where it had likely sat since its creation, this “sensational” hutch with original paint and H-hinges even caught some dealers’ eyes at the show. The Primitive House, Earlville, N.Y.

Another unique and unusual piece was a large, dark wood headboard from Log Cabin Country Primitives, Glastonbury, Conn., that dated to at least the beginning of the Eighteenth Century but seemed even earlier. Its geometric and floreate carvings are similar to those seen on bible boxes and blanket chests made in southern New England during the “Pilgrim era.” This headboard would have been an elaborate wedding gift for the offspring of a wealthy family, and its upper mortises indicate that the complete bed supported an upper canopy for hanging curtains. Beds such as these were status symbols but also built for keeping out the cold, making it necessary hardware then and now.

Homemade cupboards come in all shapes and sizes at Walker Homestead, but one was so primitive it had a wire for pulling open the door in place of a latch or a knob. Housed by the aptly named Milltown Primitives of North Stonington, Conn., the cupboard stood out with its visible layers of original cool tone colors that were noticeably absent on the clean interior surface. It was definitely “used,” but the care shown for this piece by previous owners was evident. Showing square-head nails and planed exterior surfaces on its smooth boards, the cupboard was probably crafted in the first half of the Nineteenth Century, possibly in New Hampshire.

Dough bowls attract and repel customers for the same reason: they occupy most of whatever table they sit upon. Duck Pond Antiques, Charlemont, Mass., had an example that changed the conversation by almost being a table itself. Measuring five feet by two feet, it was hand hewn from a single tree trunk. The uncommonly large bowl came with its own trestle stand that, if not exactly contemporary to the bowl, was certainly early. Todd Gerry, who owns Duck Pond with his wife Katelyn, sourced it from a New York estate but otherwise did not know the bowl’s exact origin.

Carved from a single tree trunk, this extra-large dough bowl came with its own period trestle stand to support pre-industrial bread production. Duck Pond Antiques, Charlemont, Mass.

“It actually just sold,” said Jerrilyn Mayhew of Woodsview Antiques, Sandwich, Mass., when asked about a brightly colored chest in her booth. Mayhew continued, sharing that it was found on Cape Cod, pointing out its handwrought square-head nails, original hardware and “chunky” dovetail joins on each corner. Painted on the chest’s lid in yellow and red was the faded monogram “HE” over old mustard sponge-painting that appeared to be faux grain. Chests like these were common gifts from carpenters and sailors to their sweethearts in the early Nineteenth Century and, despite extensive surface wear, it was still perfectly functional and charming storage.

A “next-level” coffee connoisseur would have struck hardware gold with a circa 1900 Universal coffee grinder in the tent of Orphan Annie’s Antiques, Barre, Mass. The grinder was made by manufacturer Landers, Frary & Clark of New Britain, Conn., which produced housewares from about 1842 to 1965. It was a tabletop size, Model 11, and still had all the “guts” for grinding that could be seen by lifting the lid. The grinder’s wood knob, handle, base and original green paint were intact, as was the drawer for collecting ground beans. With proper care, it could continue operating for another hundred years.

In our comfortable era of central air, refrigerators and freeze-drying, it’s easy to forget that most of the goods at shows like Walker House were meant to store perishable foods. Some containers were more decorative than others, and one of the smallest but most elegant was an Eighteenth Century tea caddy sitting under glass in the booth of P.J. Culley Antiques, Sterling, Mass. Carved from walnut with an inlaid bone lock plate was a rare form, figural pear caddy that had been in Culley’s family collection for almost 60 years. Culley bought the caddy from a woman in either Bolton or Berlin, Mass., whose own family had owned it for as long as she could remember. The caddy was recently appraised and in great original condition.

This rare carved walnut tea caddy dated from the Eighteenth Century and descended in a Massachusetts family until it joined the collection of P.J. Culley Antiques, Sterling, Mass.

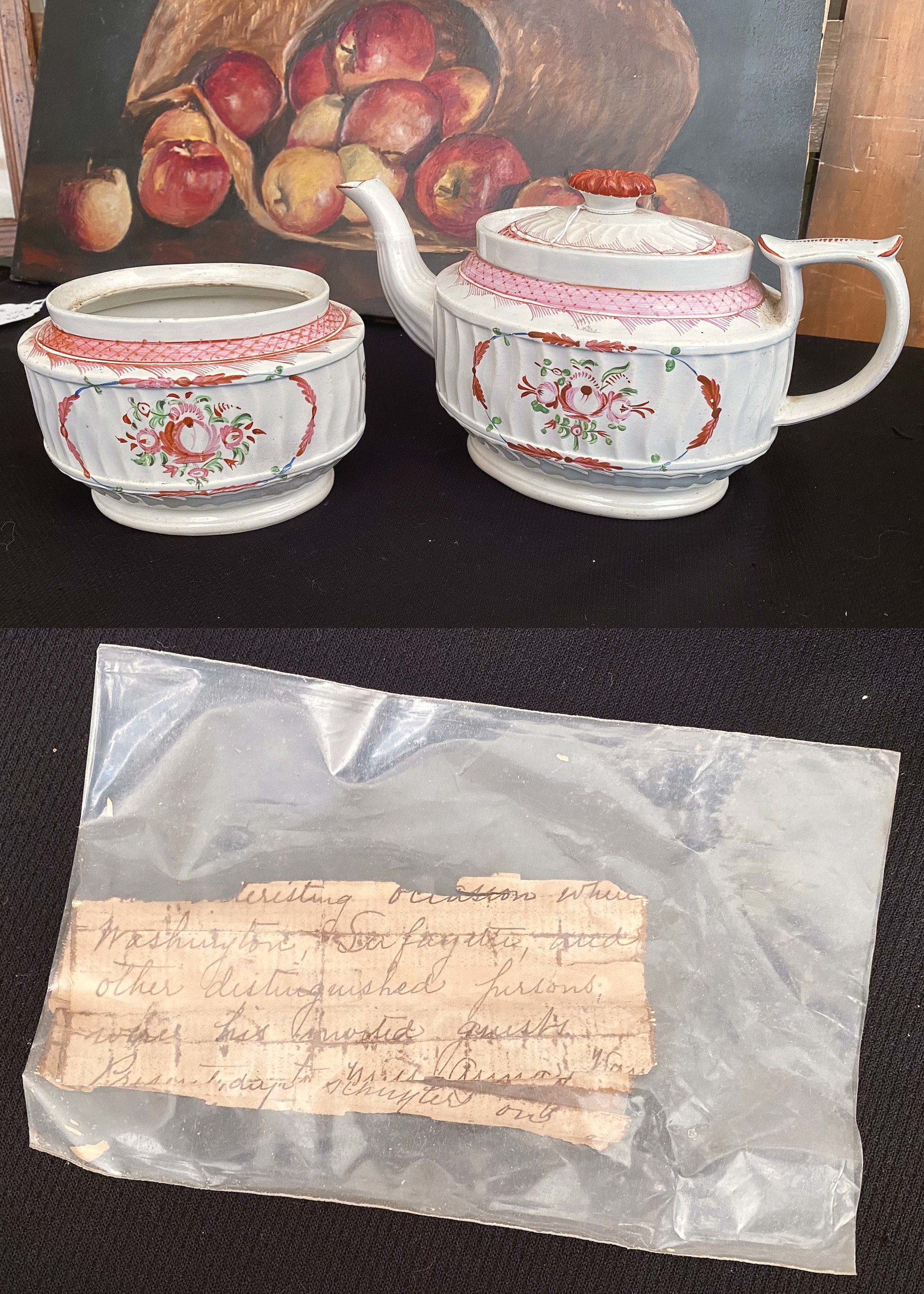

Provenance via oral tradition is one thing, but grandmother’s notes hidden inside or taped to family heirlooms offer stories that otherwise may have never been told again.

Bruce and Donna Smebakken, West Brookfield, Mass., showed a circa 1800 pearlware teapot and sugar bowl, both with hand painted decorations and unusual fluted bodies, that included no less than three notes with purchase. The first was sealed for its protection, a yellowed and flaking piece of paper showing penmanship of the period. Second was a newer transcription of that note, reading that these were used by Major General Philip Schuyler (1733-1804) while hosting “Washington, Lafayette and other distinguished persons.” They were presented to Miss Anna van Ingen by “S.E.,” who may have been related to William “Billy” van Ingen (1760-1800), a clerk to the Schenectady, N.Y., businessman Henry Glen (1739-1814) during the Revolutionary War.

More local history was revealed with a skillfully rendered watercolor of a bullfrog, inscribed with the name of Eliphalet Dyer (1721-1807), a colonel in the French and Indian War (1754-63) and a Connecticut delegate in the Continental Congress, who later served as a representative and chief justice for that state. The painting’s subject is a possible participant of The Battle of the Frogs, an incident that occurred in the summer of 1754. Following the war’s outbreak, a horrendous noise was heard late one night that raised alarm in Dyer’s hometown of Windham, Conn., and some claimed to hear his name called out amongst the thunderous din. The next morning, hundreds of dead frogs were discovered with no certain cause of death, and the “battle” became the subject of a folk ballad, a comic opera and a running joke throughout the area. Frogs are now Windham’s community mascots, commemorated by giant copper statues on Willimantic’s Thread City Crossing, or the “Frog Bridge.”

The Walker Homestead is at 19 Martin Road, and its next Antiques & Primitive Goods Show will take place on September 27. For information, 508-867-4466 or www.walkerhomestead.com.