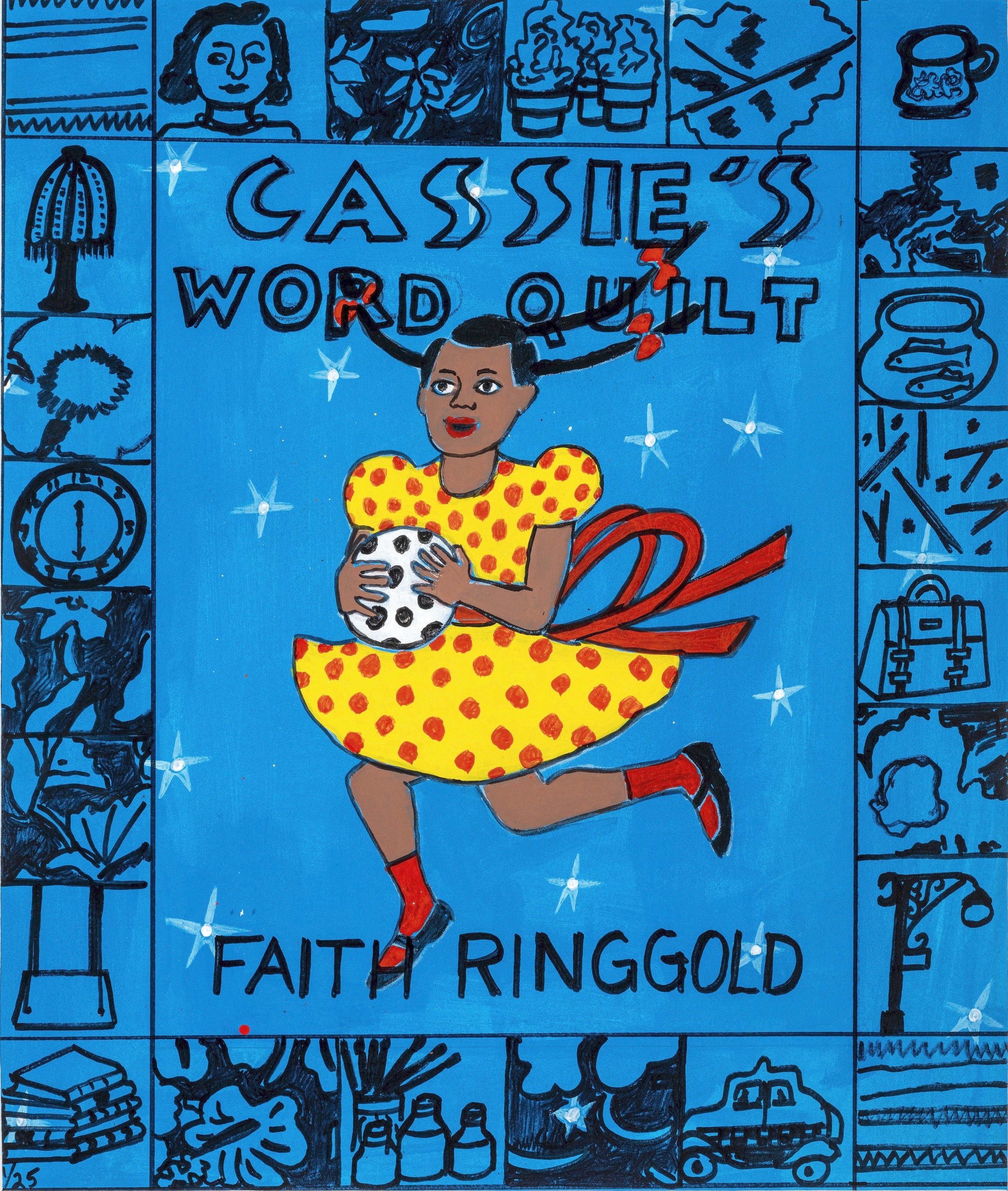

Cassie’s Word Quilt by Faith Ringgold, 2002, acrylic and marker on paper.

By Andrea Valluzzo

Images courtesy the Estate of Faith Ringgold. © Anyone Can Fly Foundation.

Photography by Paul Mutino.

ATLANTA — Artist-activist Faith Ringgold (American, 1930-2024) is renowned for her lushly painted “story” quilts and her paintings that shared the experiences of Black Americans, many of which she translated into children’s books. Few know quite how prolific she was in her interdisciplinary career, or that her desire to make art approachable to children was shaped by her early years teaching art in the New York City public schools for nearly two decades. Growing up in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City and teaching young children there gave her keen insight into how children see the world around them as well as the importance of community and activism.

“There are so many people that know and love Faith Ringgold and have no idea she wrote this many books and I think they will love getting to discover more of these incredible stories and illustrations,” said Andrew Westover, the Eleanor McDonald Storza deputy director of learning and civic engagement at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. He curated “Faith Ringgold: Seeing Children,” a large retrospective exhibition on view at the museum from June 27 through October 12. “Faith Ringgold did a wonderful job looking at the world with this sort of clear-eyed criticality intact yet always balanced with a sense of hope and possibility. I think that’s something that our society sorely needs right now.”

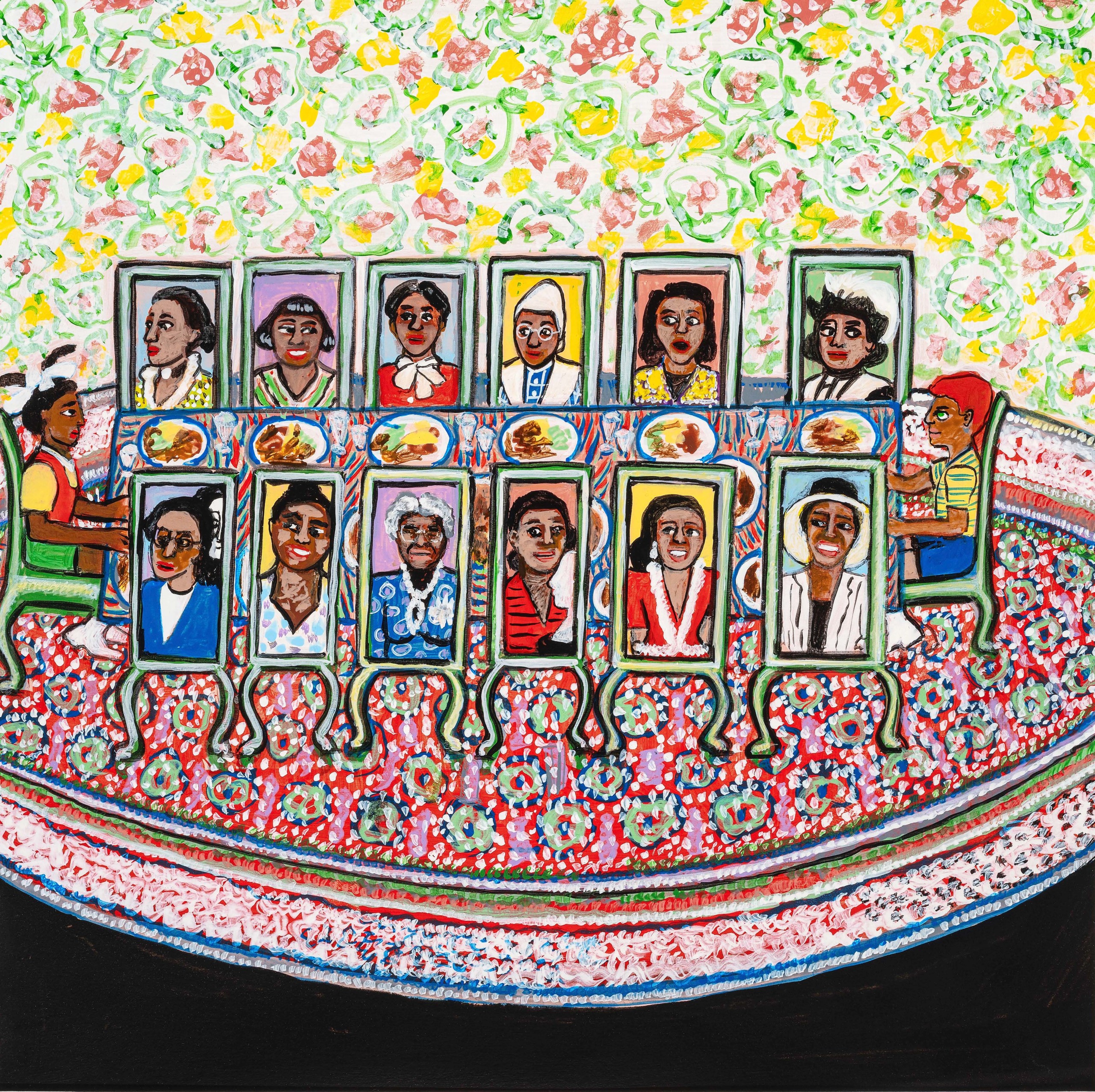

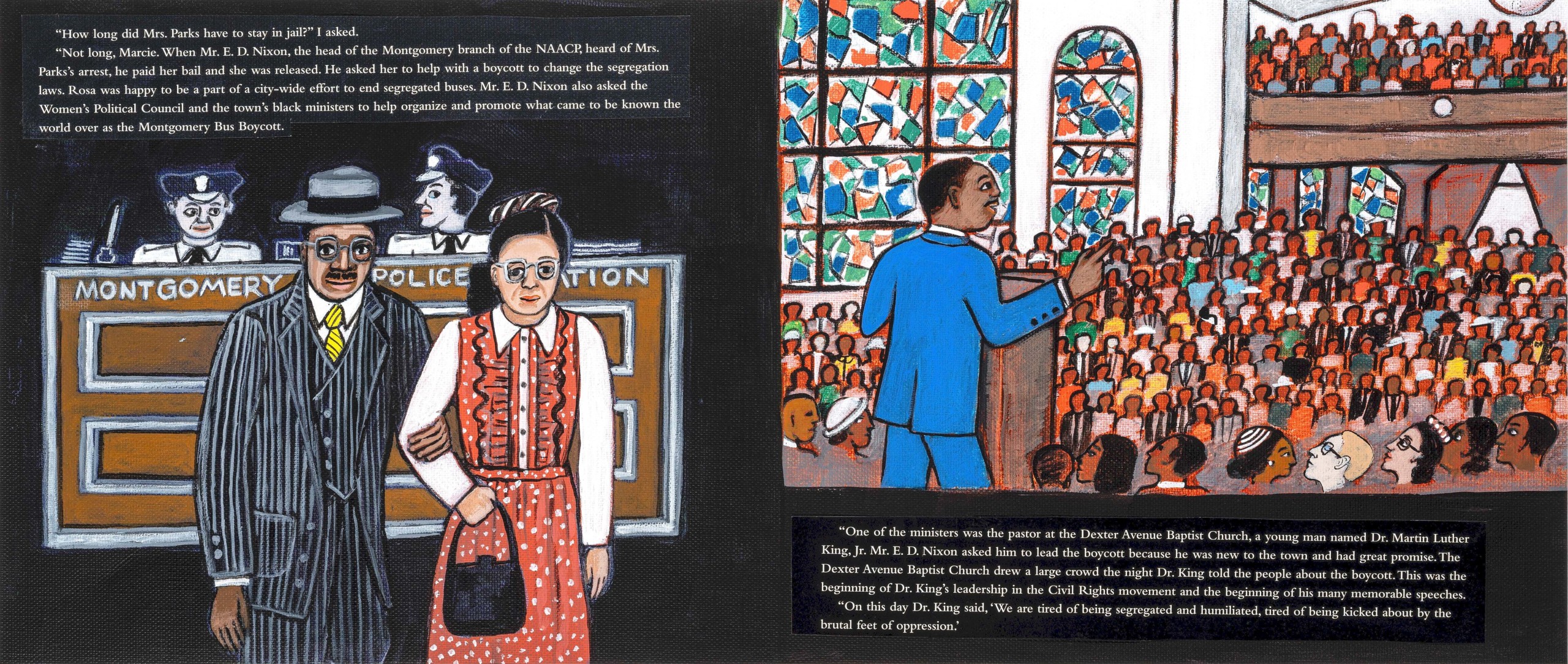

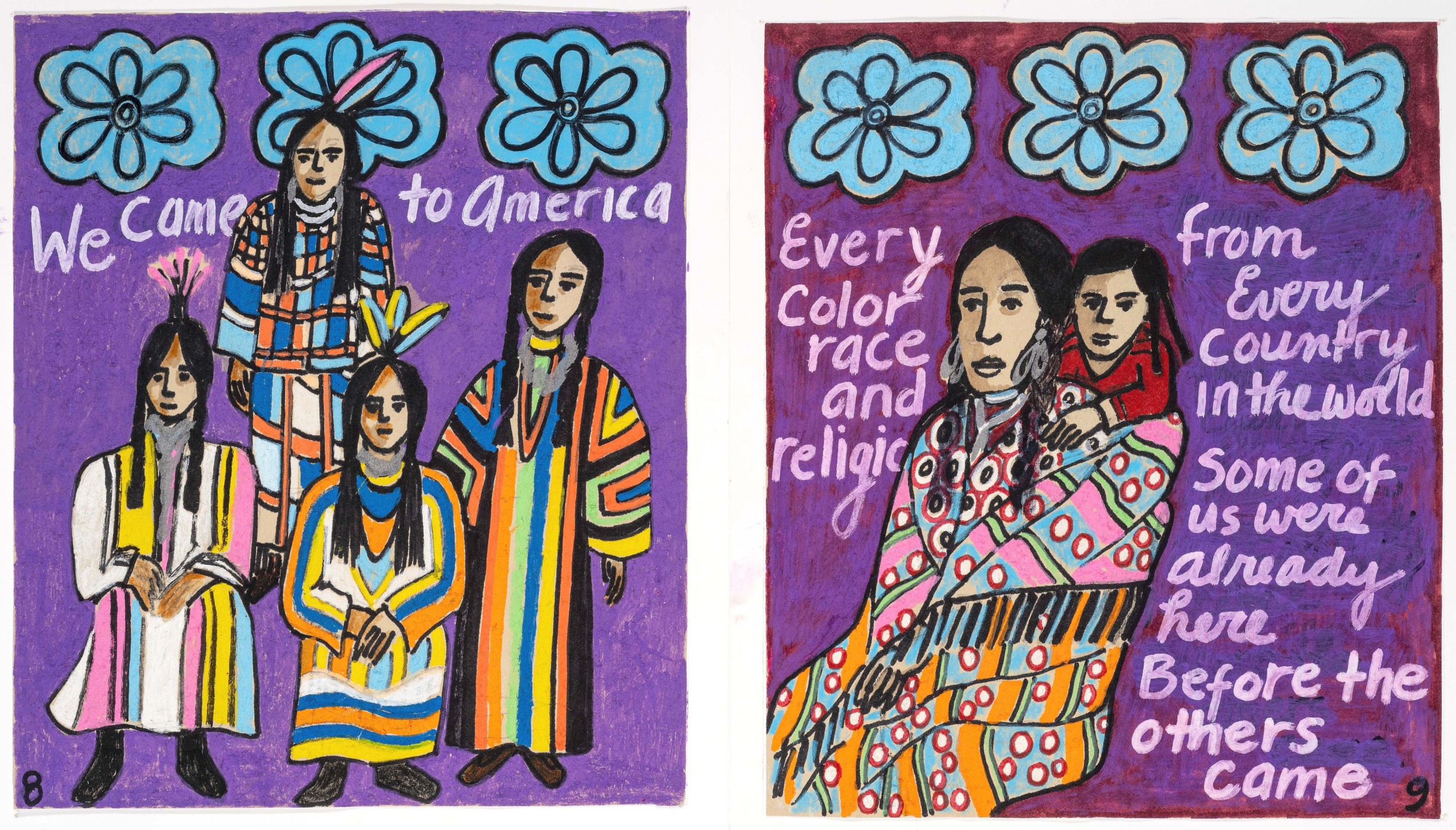

The exhibition, which comprises more than 100 works, is the most inclusive showing so far of her original paintings and drawings she created for more than a dozen children’s books. Several books are presented in their entirety, including We Came to America (2016), Invisible Princess (1999), Tar Beach (1991) and Cassie’s Word Quilt (2002). “Seeing Children” also includes original paintings from If a Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks (1999) and Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House (1993).

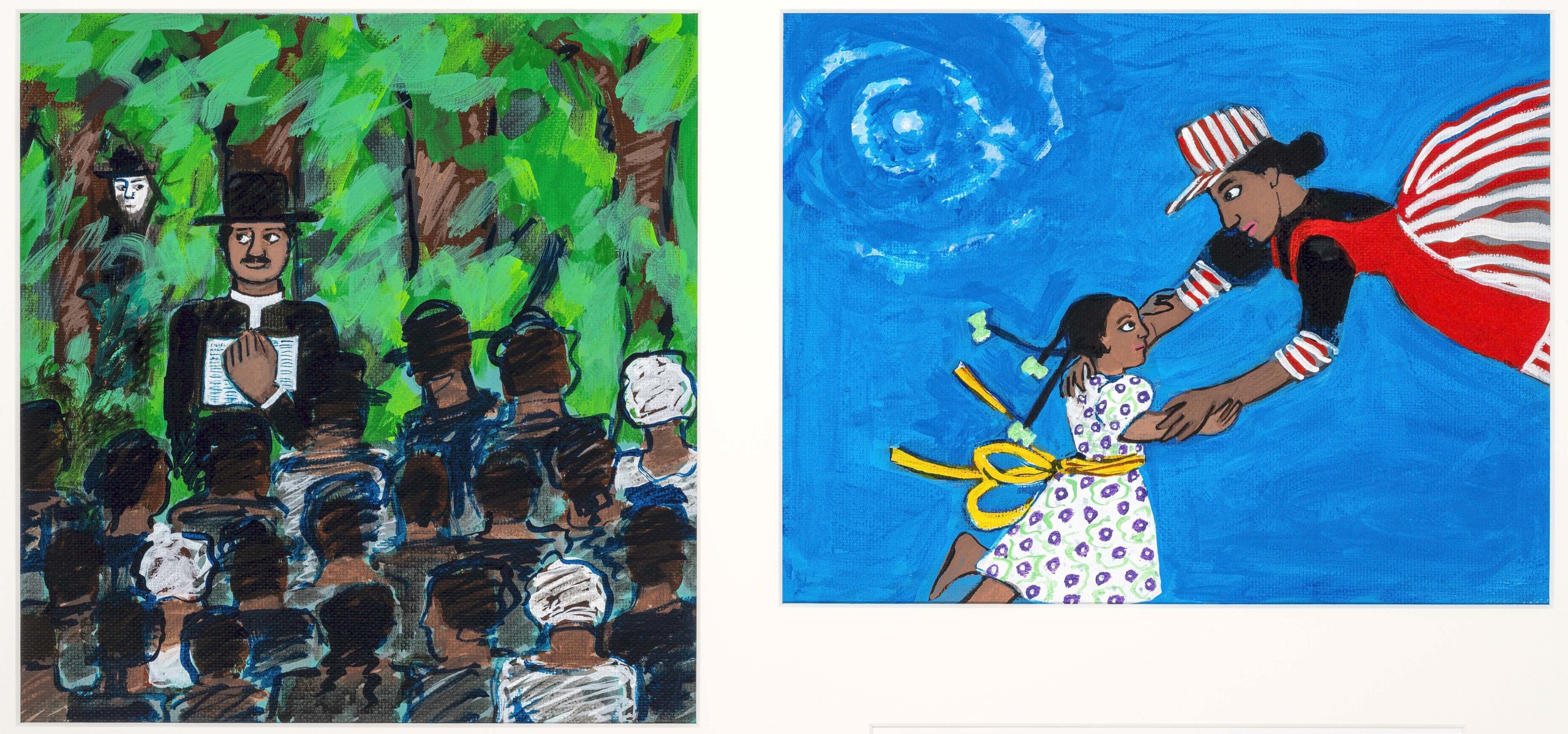

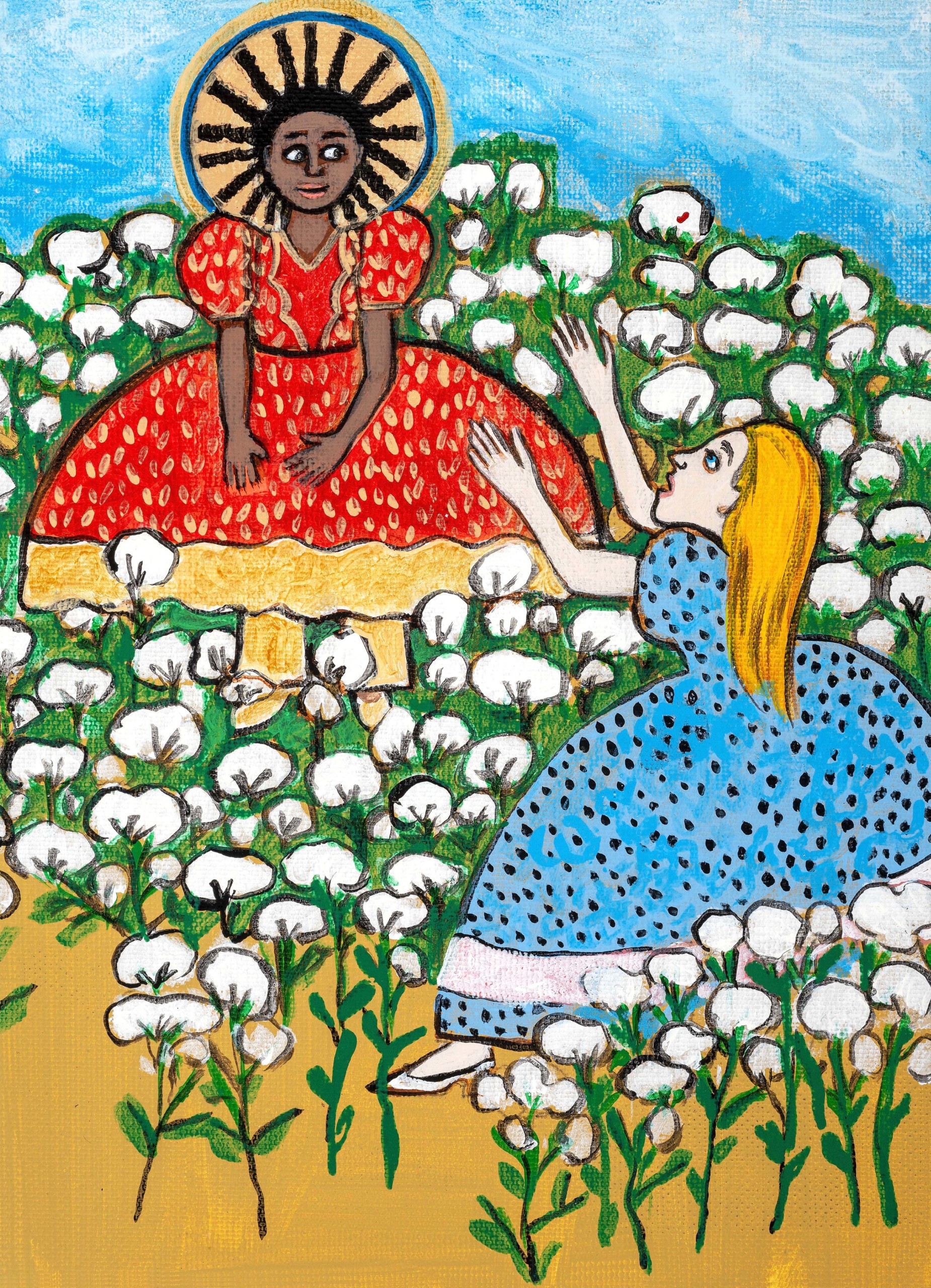

The Invisible Princess, cover, by Faith Ringgold, 1999, acrylic on canvas paper.

Several works and objects have not been publicly shown before and Ringgold’s estate, with whom Westover collaborated, was the source of several key artifacts from her personal collection.

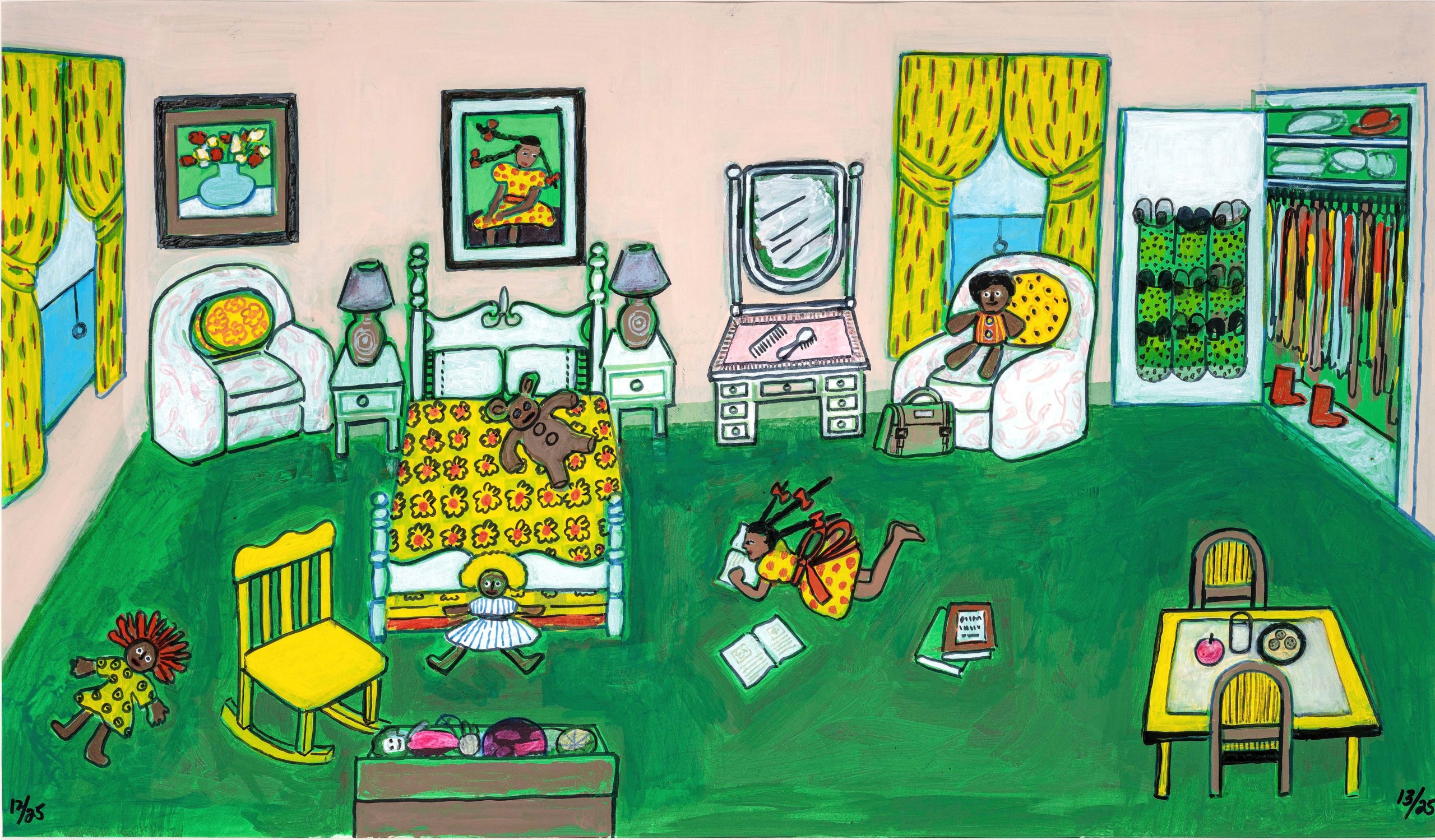

From Ringgold’s home came a child-size yarn and cloth doll along with a chair, both dating to 1994, representing one of her chief protagonists, Cassie Louise Lightfoot, who appears in several books. When Ringgold’s books soared in popularity, her publisher, Crown, partnered with manufacturers to create merchandise based on her books, including Cassie dolls. Most of the resulting dolls were small but the doll in this exhibition was one of a few made life-size. Ringgold kept the doll and chair in her home and she even drew the doll’s face by hand, which was later screen-printed for mass production. “This is the largest and most comprehensive show of her children’s picture book illustrations. There simply has never been a show before of this scope,” he said.

Organized thematically, the exhibition explores three themes that resonate through the dozen-plus children’s books Ringgold authored and illustrated: “American Histories,” “Stories We Tell” and “Seeing Children.” Not only were children, particularly Black children, at the center of Ringgold’s stories, but she took care to turn them into storytellers and artmakers in their own right. Her books show the way they see the world around them and how they are seen.

Designed with a quilt-like border, is Faith Ringgold’s illustrated cover of Cassie’s Word Quilt, 2002, acrylic and marker on paper.

“Throughout her work, Faith Ringgold’s books really help us understand the interrelationship between how children see themselves, how adults see children and then how children themselves are seers in sort of an expansive sense…and can see and imagine futures and possibilities that adults don’t always see,” Westover said. “Throughout the exhibition, you are seeing through the protagonist that she created in the storylines, narratives and these incredible images how Faith Ringgold’s life and experiences help her see children in new and beautiful ways.

Ringgold was an accomplished artist, who was equally adept at painting, quilting and sculpture and she was also well known as an activist. Westover said people often forget her time teaching in New York City schools and then later at the collegiate level, at the University of California, Irvine. “This lifelong grounding as an educator really transformed how she saw human development and particularly how she understood the capacities of children.”

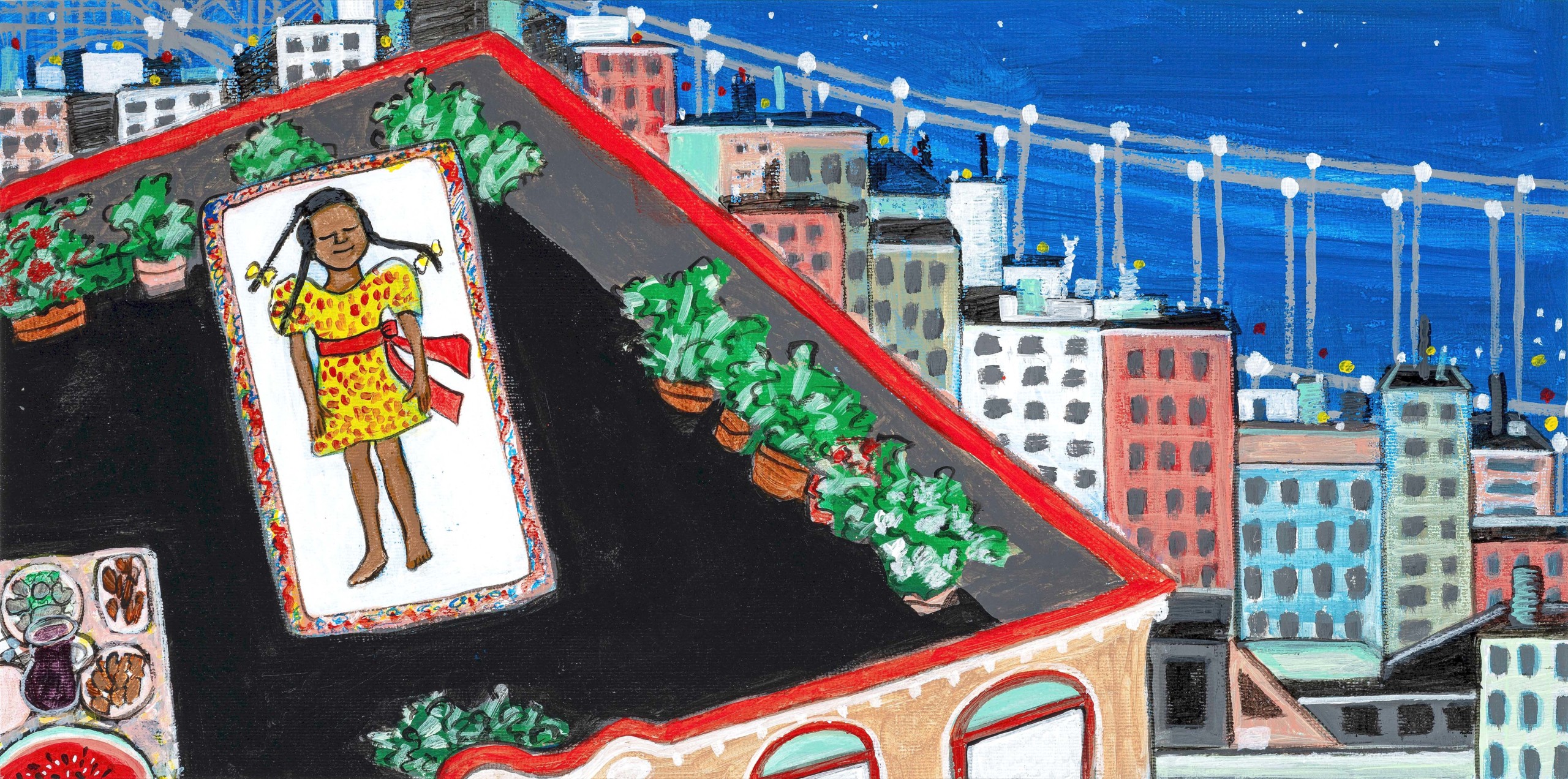

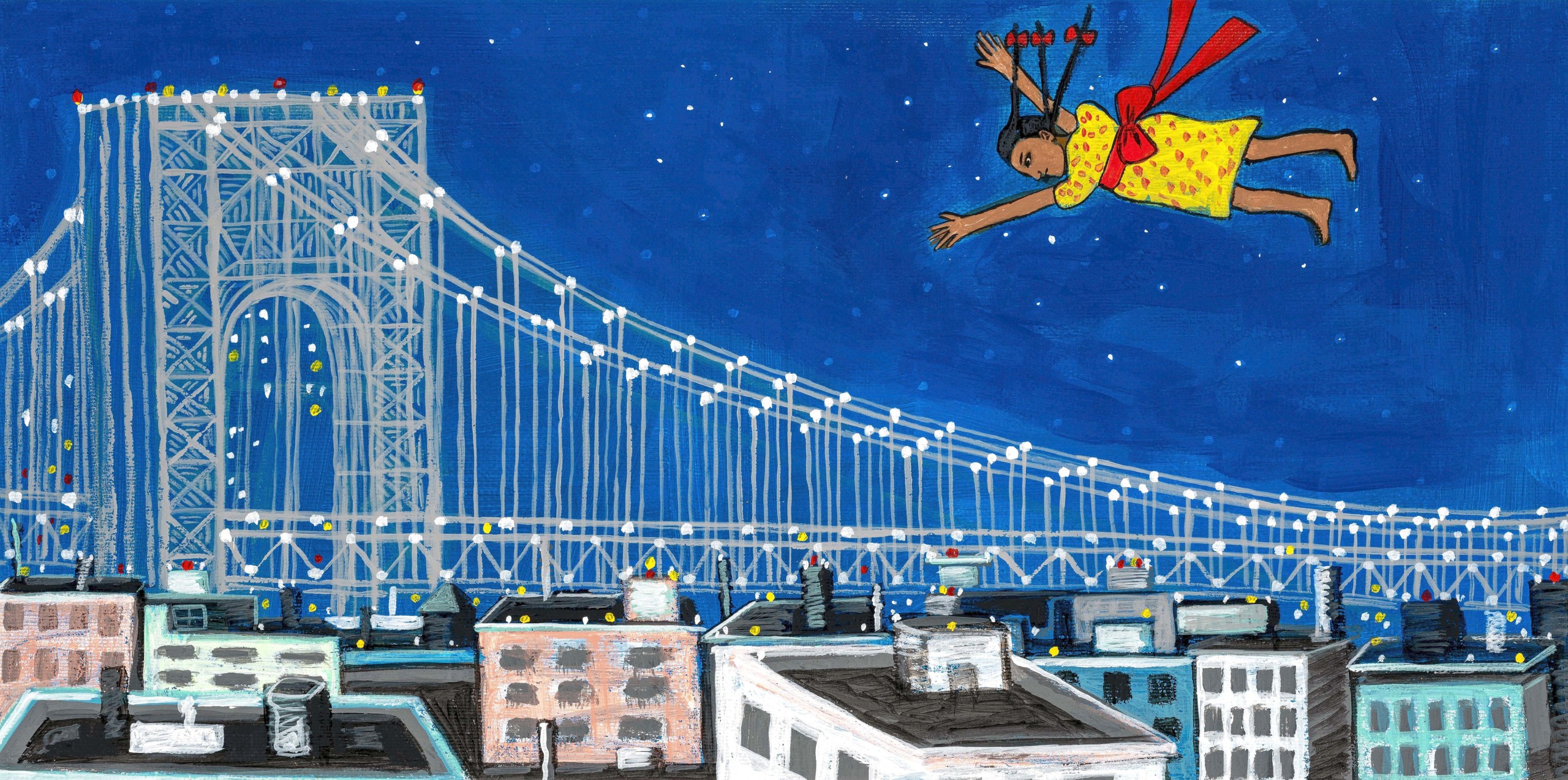

The most famous of her books, Tar Beach, aptly ties into the exhibition’s themes of “seeing” as it centers on a young girl, Cassie Lightfoot, who dreams of being able to go where she wants. Relaxing one night on the roof of her apartment building in Harlem, her “tar beach,” she is able to fly over the city. Several illustrations and pages from her book are featured in an immersive display in the exhibition.

“Her children’s books are really spectacular. Her first, Tar Beach, was written and published in 1991 and it was an immediate commercial and critical success,” he said. “Cassie imagines herself just flying over the sea and everything she surveys. It is this beautiful ode, an imaginative exploration of childhood and really encourages young people and their families to think about how we perceive the world around us.”

Tar Beach, “I will always remember,” by Faith Ringgold, 1991, acrylic on canvas paper.

A standout in the “Stories We Tell” section are works relating to Ringgold’s book, The Invisible Princess, which tells the story of a child of enslaved parents. Magic has made her invisible to all but a blind girl, protecting her from being enslaved. Later on, she helps bring freedom to her parents and the other enslaved people on the plantation.

Ringgold’s book illustrations frequently use a child’s eye-level perspective. In the final section, works like those created for her 2016 book, We Came to America, also utilized bright and vivid colors to share the histories of the many immigrants who emigrated to the United States from different places and for different reasons. In a 2014 work for Harlem Renaissance Party, the artwork features a bright red background against which several figures are gaily dancing, capturing the joie de vivre of this golden period of Black culture. The text and figures sometimes float on the page, prompting the reader to bring the story elements together in their own way as the story plays out.

“The things that are really fascinating about her artistic practice is that these works are so vibrant; they are visually stunning,” Westover said. “She did a lot of work where she was juxtaposing images of people or figures on these planes and washes of color so it’s almost this blend between a modernist sensibility that also pulls from her childhood [during the Harlem Renaissance] and the imagery of that time blending with her textile practice. A lot of these images will have quilted borders or even the narratives themselves can feel sort of like quilted together.”

My Dream of Martin Luther King, “Young Martin was Happy to Read the Signs,” by Faith Ringgold, 1995, acrylic on canvas paper, printed text in mat window.

Her design choices, such as how she uses text alongside images, are interesting and unique, he explained. Her images, even those created decades ago, feel contemporary and fresh. Ringgold also excelled at depicting historical figures with unerring accuracy “such that they can be recognized and representative,” he added.

Children’s picture book art has not always gotten its due in the museum world, but that seems to be changing of late. There is the Eric Carle Museum in Massachusetts, of course, which primarily focuses on that particular author, but, overall, this genre has largely been overlooked by major museums. The High has a longstanding commitment to celebrating children’s picture book creators, though, and Westover noted that the Denver Art Museum recently mounted a major exhibition of Maurice Sendak’s illustrations. “I firmly believe this is art that deserves a place in museums and in museum collections and I think increasingly we are seeing art museums broadly understand that to be true,” he said. “We are starting to see this break into the broader world of major institutions allowing space for and really rightfully privileging this work as artistic in its own right.”

The High Museum of Art is at 1280 Peachtree Road. For information, 404-733-4400 or www.high.org.