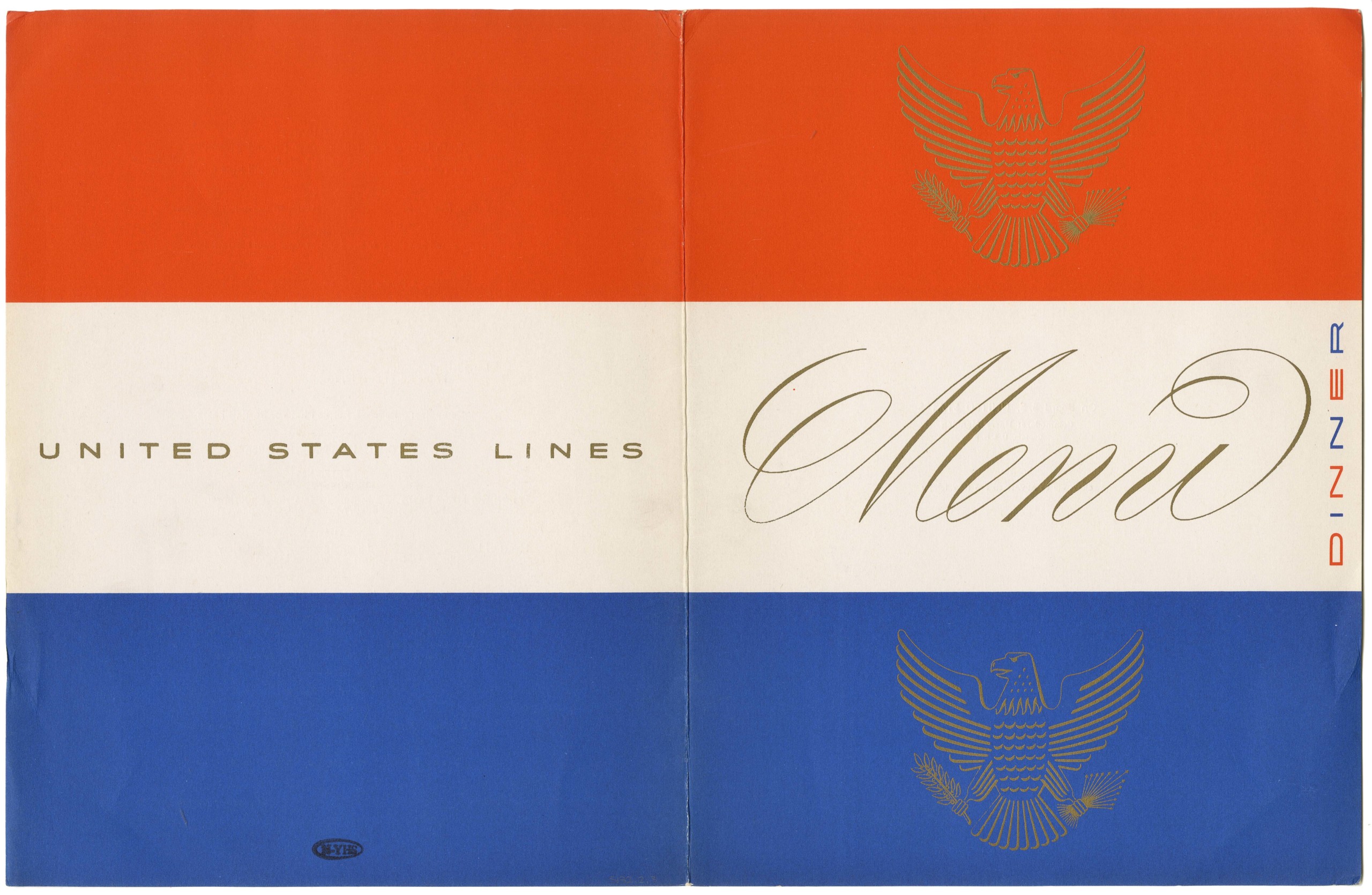

SS United States dining menu, July 24, 1952. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

NEW YORK CITY — Traveling has always been a summer pastime, but most travel experiences today offer little in the way of sustenance; for travelers who do not bring their own snacks purchased from airport vendors prior to boarding they must rely on prepackaged food and beverages distributed from in-flight trolleys. Those who take to the rails can find greater options, from snacks and fast-food options available in bar cars on regional lines to limited seasonal menus on lengthier trips. Cruises offer the most choice from casual dining and all-you-can-eat buffets to elegant restaurants, some of which are even overseen by top chefs.

One of the summer exhibitions at The New York Historical (NYH) travels back in time to explore how ocean liners, trains and airplanes fed passengers in the early Twentieth Century. “Dining in Transit” showcases how travel dining evolved, from hiring French chefs to crafting signature dishes to exploring how the industry was shaped by deeper stories of gender and race. Curated by Nina Nazionale, director of library curatorial affairs and research, the exhibition is anchored in the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library’s dining menu collection and features other distinctive objects from The New York Historical’s collections: souvenir menus, promotional recipe books, employee handbooks and collectible tableware, among other artifacts.

“The New York Historical’s dining menu collection was my inspiration,” Nazionale told Antiques and The Arts Weekly. “Menus provide us with so many historical insights — about dining trends, modes of travel, shifting social mores, art and design, promotion and marketing. The dining menus that were designed to celebrate holidays on airplanes really caught my attention. I started to think about how, logistically and financially, that was possible.”

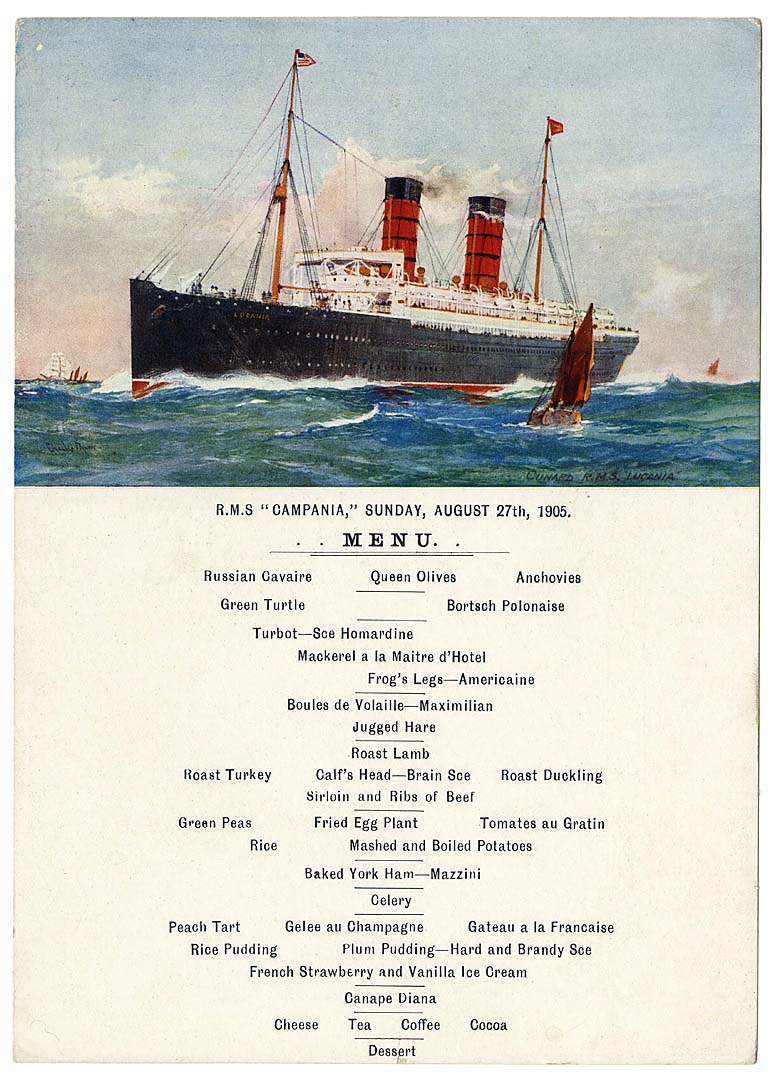

Cunard Line, RMS Campania menu, August 27, 1905. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical.

The curator noted that while there have been exhibitions about food and dining at the NYH and elsewhere before, “Dining in Transit” is the first such exhibition to focus specifically on food service on ocean liners, trains and planes.

To prepare for the show, Nazionale studied related ephemera and digitized articles from newspapers, magazines and trade journals that were published in the early to mid Twentieth Century after finding that secondary sources “tended to be broad surveys of the dining in transit or else in-depth examinations of one particular company.”

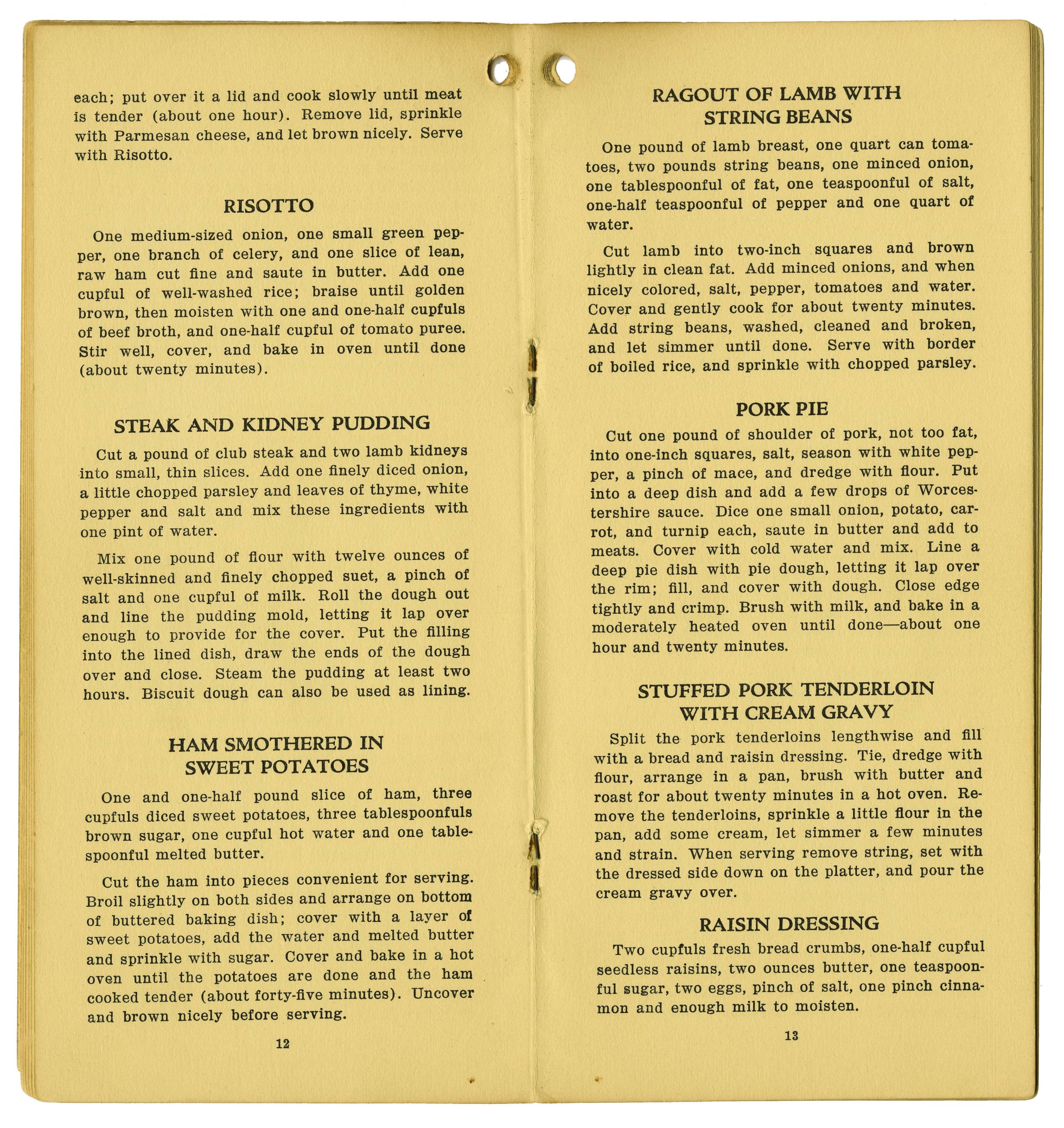

“There were a number of revelations: an early instance of cross-branding in which the Hamburg-American ship line partnered with London’s Ritz Carlton hotel and renowned Parisian chef Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935) ended up supervising kitchens on at least two ocean liners; trains had very small, well-equipped kitchens in which entire meals were cooked from scratch, including train-made pies; that Swiss-trained chefs were hired on airlines, and, in one instance, they formed a club in the tradition of Les Amis d’Escoffier.”

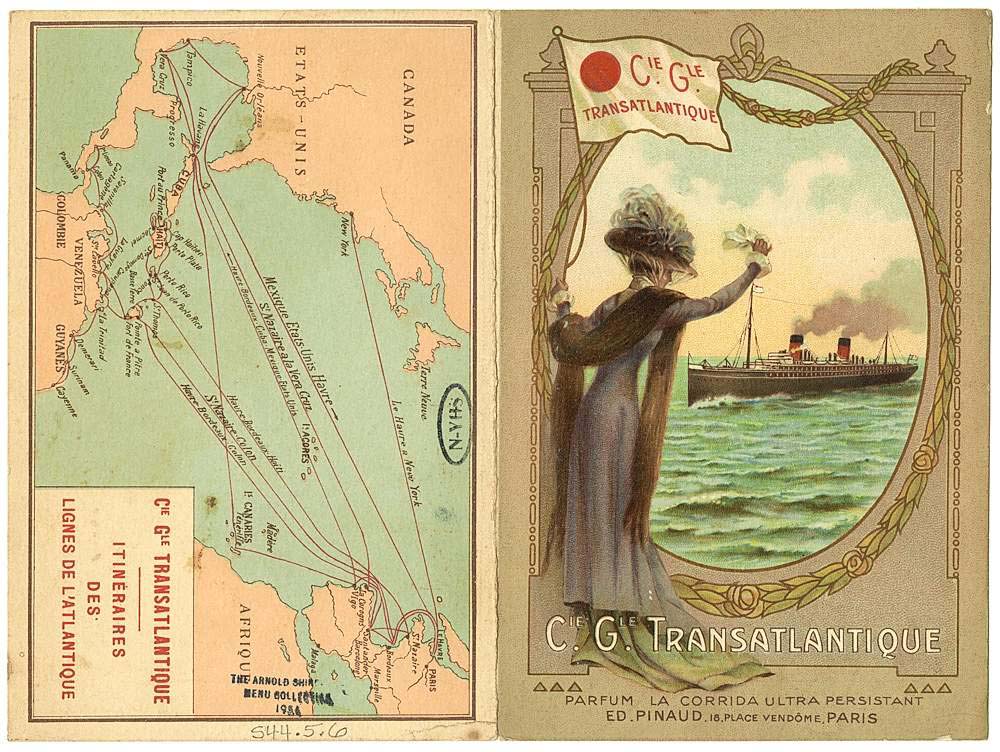

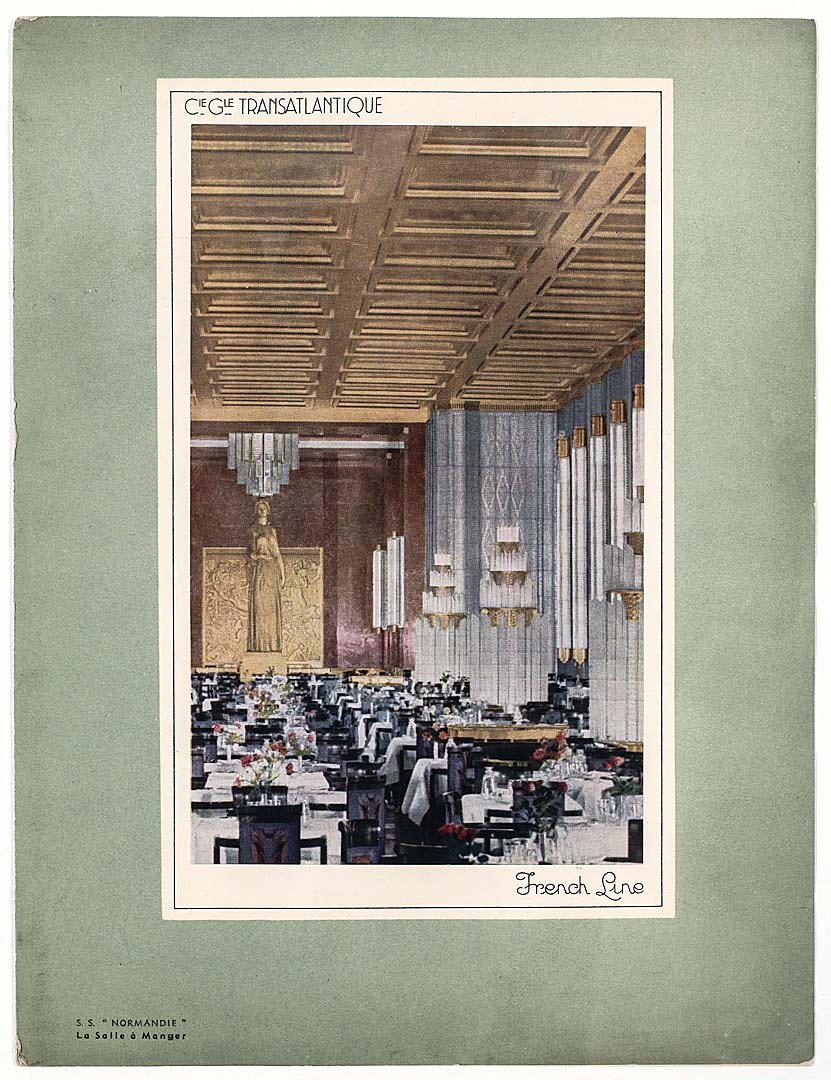

With sea-going travel, fine dining elevated the travel experience for the wealthiest passengers. After US laws drastically reduced immigration from eastern and southern Europe in the 1920s, ships wisely rebranded their “steerage” classes to “tourist third class” and made available different levels of dining to cater to the various passenger classes.

SS Normandie French Line, dinner menu, November 22, 1938. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical.

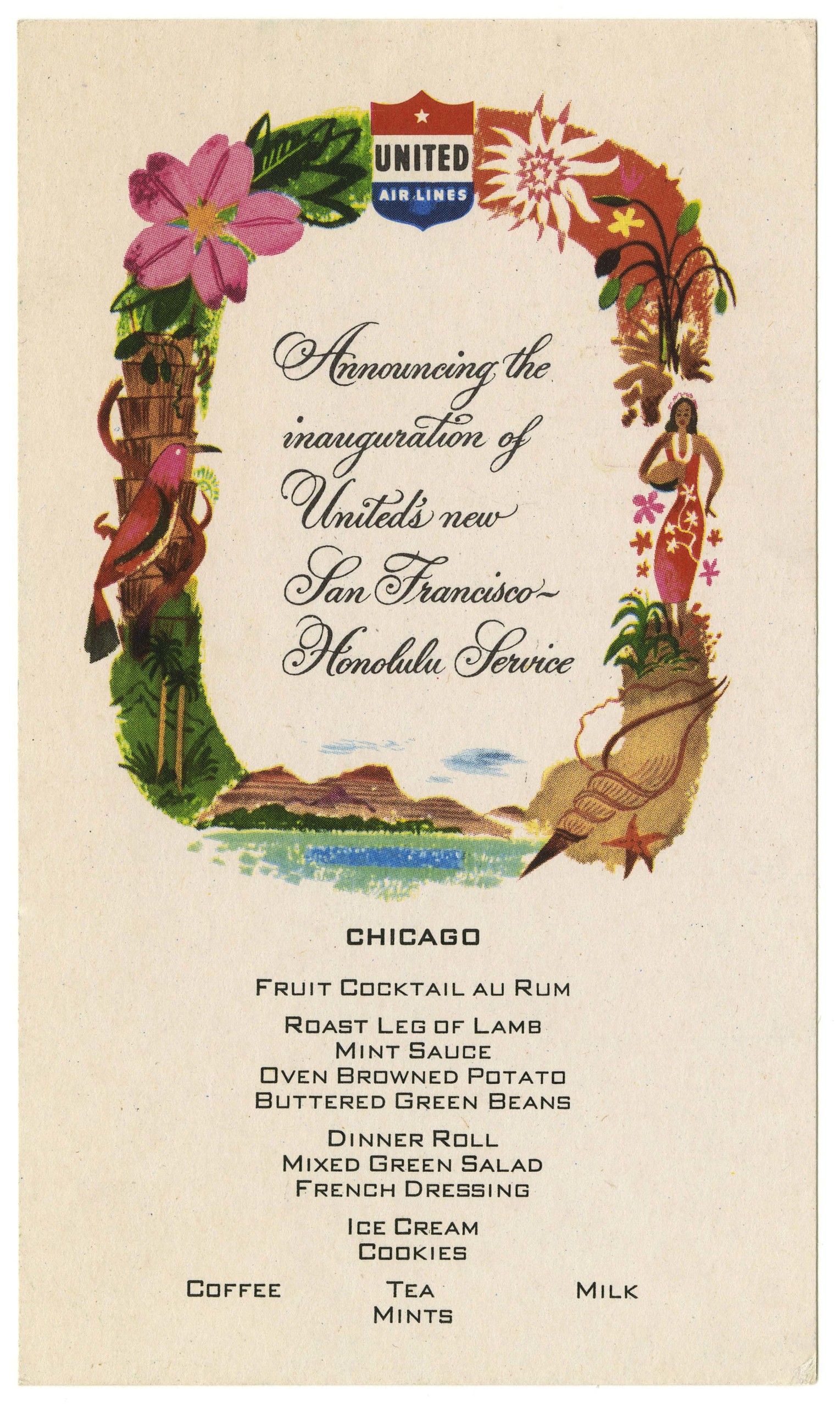

The SS United States, which was designed by naval architect William Francis Gibbs, built between 1950-51 and launched in 1952, helped establish the United States in the transatlantic ocean liner business. Meant to function as both a passenger ship and a troop ship (if the need arose), the ship was built mostly of aluminum to be fireproof. Passengers dined off tableware decorated with the patriotic motifs of flags, stars and stripes, and dined on regional specialties, including lobster Newburg, California asparagus and a “baked Idaho.”

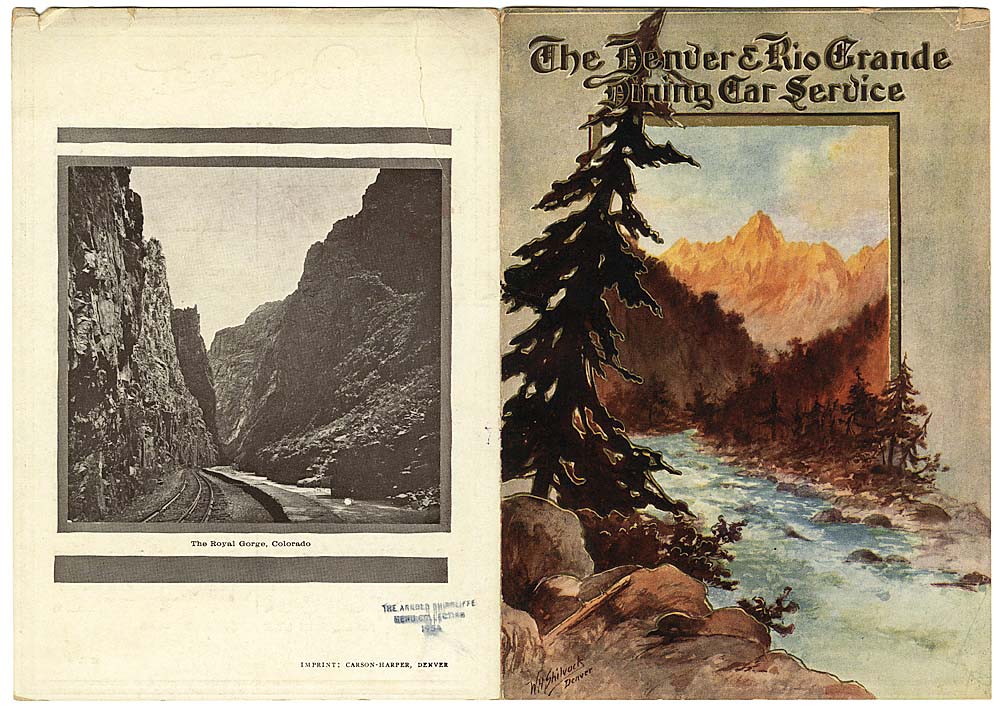

Dining cars on trains first appeared in 1868. They were introduced by the Pullman Palace Car Company, which was already known for its sleeping berths. As meal service flourished across railway lines, regional cuisines were also given prominence. Chesapeake Bay seafood — clams on the shell and boned shad — were worked into the on-board offerings of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad while on the New York Central Railroad’s Twentieth Century Limited trains, diners might follow a meal of Fricassée of chicken, prepared in the Southern style, with “NYC” French vanilla ice cream.

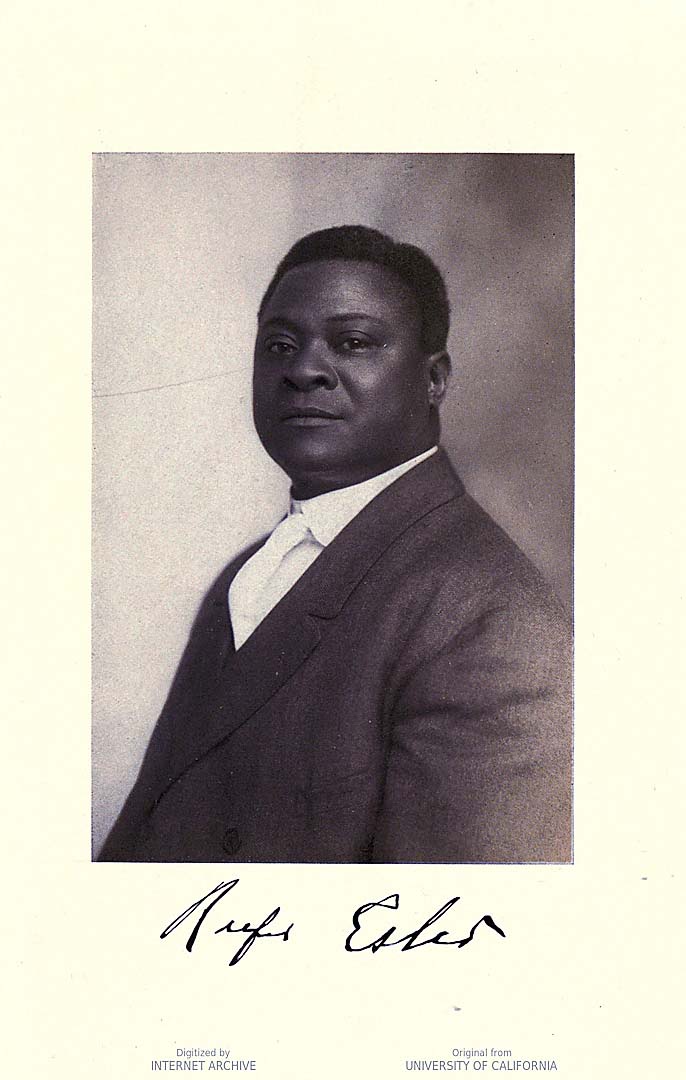

Included in the exhibition is a copy of Good Things to Eat as Suggested by Rufus, a 1911 cookbook written by Rufus Estes, who was born into enslavement in Tennessee and worked for Pullman between 1883 and 1897, later on private railroad cars owned by wealthy white owners. Estes’ book includes recipes for some standards of African American cuisine, including tea cakes and velvet cake. It was published at a time when Black passengers often faced segregation on board and Pullman porters, cooks and waiters were paid poorly and subjected to taunts and insults by passengers.

Rufus Estes (1857-1935), Good Things to Eat As Suggested by Rufus, 1911. Photo credit: Via HathiTrust.

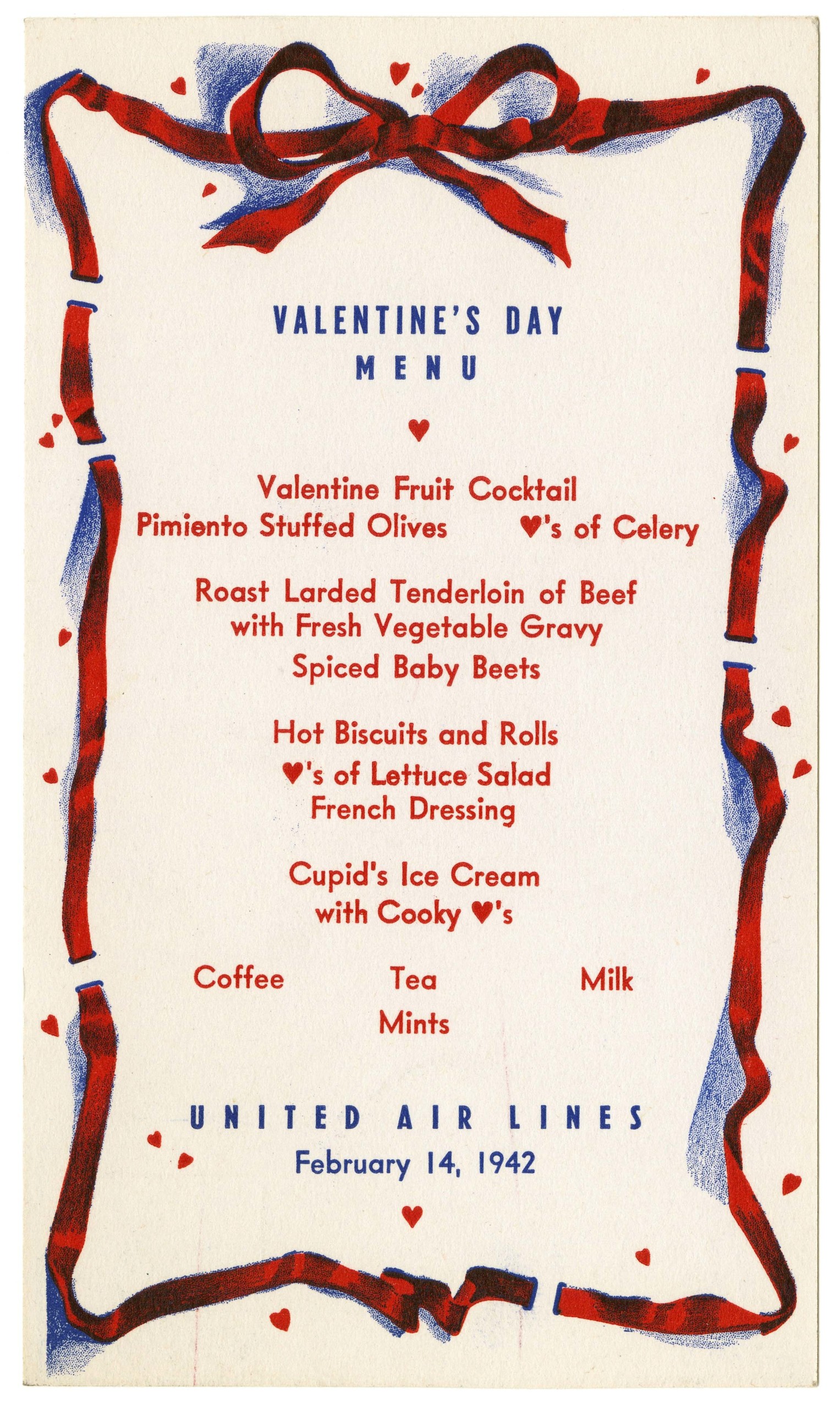

Air travel brought new opportunities — and challenges — for women, who were recruited as stewardesses or air hostesses with promised of adventure but subjected to strict physical standards; the first Black stewardess was not hired until 1958. In addition to serving meals, stewardesses were expected to load luggage and tend to sick or anxious passengers. The first meals commercial passenger flights served picnic-style meals of cold fried chicken or sandwiches. In 1936, United Air Lines opened its first flight kitchen where the effects of altitude and cabin pressure were considered. By the end of the 1930s, larger planes could accommodate onboard kitchens and the temperatures of ingredients could be better controlled.

United Air Lines would hire European chefs, featured them on menus, and recipe booklets were published, including Favorite Recipes of Mainliner Chefs, published by United Air Lines in 1954.

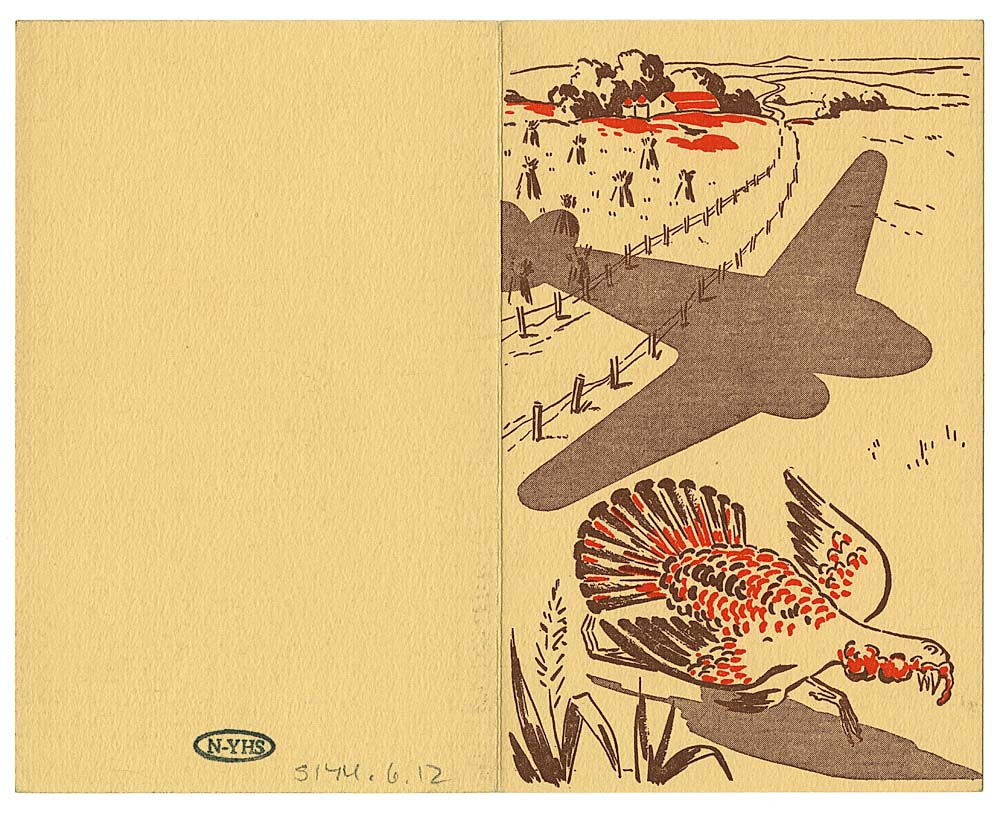

Airlines introduced seasonal, holiday-themed offerings. An American Airlines Thanksgiving menu dating to the 1930s-40s is among the objects in this section. Also highlighted is a uniform hat owned by Chicago-native Shirley Kubik, who worked as a TWA air hostess from June 1957 to October 1958.

Thanksgiving menu, American Airlines, late 1930s-early 1940s. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical.

Following World War II, airline travel surged and three innovations made it easier for airlines to feed their growing customer base: food could be frozen in a way that maintained flavor and freshness, pre-cooked meals could be flash-frozen in a Sky Plate and the meals could be reheated onboard using a Whirlwind Oven, a precursor to the convection oven.

Nazionale hopes exhibition viewers come away realizing “[h]ow impressive it was that ship, train and plane companies transformed what was a necessity on long trips — eating — into a dining experience that would long be remembered thanks to alluring souvenir dining menus.”

“Dining in Transit” is on view through October 26.

The New York Historical is at 170 Central Park West, at Richard Gilder Way (77th Street). For information, 212-873-3400 or www.nyhistory.org.