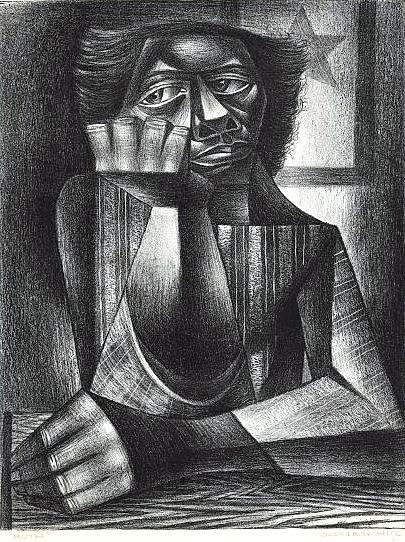

“Portrait of An Artist” by Ivan Gregorovitch Olinsky, 1930, oil on canvas, 36 by 30 inches. Permanent Collection, The Art Students League of New York.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY — The Art Students League is an unusual name for an art school, when you think about it. The word “league” usually refers to a diplomatic entity (League of Nations), or a sports organization (Major League Baseball), or an advocacy group (League of Women Voters). And yet why should it be the exception, in an art world of academies and institutes? A league is, after all, a coming together of people united in a common purpose, exactly what the Art Students League strove to do on its founding in 1875 (before any of those mentioned above, for the record). Accordingly, “Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150” brings together art and artists who have intersected the League through its long history, united by its mission to make fine art education accessible to all. “Shaping American Art” is on view at the Art Students League in Manhattan through August 17.

The exhibition, explains assistant curator Esther Moerdler, is the “capstone” offering in a year-long celebration of the League’s sesquicentennial. She co-curated the exhibition with Ksenia Nouril, formerly the League’s gallery director, and an accompanying book, 150 Stories: Lives of the Artists at the League, was edited by the League’s archivist, Stephanie Cassidy, with some 140 different contributors. The book, whose title riffs on Giorgio Vasari’s Renaissance-era Lives of the Artists, encapsulates two distinct aspects of the League’s stewardship of its own history: its propensity for making lists to keep track of all those who have entered its classrooms, and its enthusiasm for discovering and telling stories about those individuals’ experiences there. “Shaping American Art” does the same with its assembly of work by nearly 100 League artists, organized loosely around various themes and throughlines.

“Night Flight” by Rockwell Kent, 1941, chiaroscuro wood engraving, 8½ by 6 inches. Permanent Collection, The Art Students League of New York.

An early section on life drawing reflects one of the main reasons for the League’s founding by a group of art students and teachers who broke away from the National Academy of Design. In the fall of 1875, the future of the Academy’s art school division was unclear, leaving its students uncertain about whether their education would continue. In addition, many of those students had grown frustrated with the Academy’s conventional approach to instruction, including drawing from plaster casts instead of from life, dividing classes by gender and restricting women from working with nude models. From the first, the new Art Students League addressed those complaints (although not without controversy). Rough drawings by Robert Henri and George Grant Bridgeman suggest how the League broke those boundaries in its classrooms, while studio nude by Kenneth Hayes Miller demonstrates how that training manifested in the full maturity of an artist’s career.

The presence of such classroom works in the League’s permanent collection — composed entirely of artists who studied or taught there—conveys one of its great strengths. Moerdler notes how the collection “ties together…lineages of instructors and students over time.” One case in point is Georgia O’Keeffe’s darkly representational “Dead Rabbit and Copper Pot” of 1908, which seems utterly contextless in her career unless you know that she studied at the League with William Merritt Chase, whose “Fish Still Life” of the same year (he famously did fish paintings as in-class demonstrations) shares the same murky background, angled composition and yet another copper pot. One of those great League stories emerges from Chase’s classroom, where O’Keeffe was a classmate of the portraitist Eugene Speicher. O’Keeffe “won best in class with that painting,” says Moerdler, and the League immediately acquired it for their collection. O’Keeffe later recounted in her memoir (as Linda M. Grasso writes in 150 Stories) how Speicher continually harassed her to sit for him, finally cornering her in a stairwell and saying, “It doesn’t matter what you do. I’m going to be a great painter and you will probably end up teaching painting in some girls’ school.” She “begrudgingly” let him do the portrait, Moerdler says — it is also included in the exhibition — but “history laughed” in the end, with O’Keeffe becoming the undisputed household name.

“Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe” by Eugene Edward Speicher, 1908, oil on canvas, 29¼ by 25¼ inches. Permanent Collection, The Art Students League of New York.

Nouril points out that the show strongly demonstrates the “importance of women at the League,” not just O’Keeffe but also photographer Berenice Abbott; printmaker, painter and satirist Peggy Bacon; sculptor and philanthropist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and others. Additionally, works like Ivan Gregorovich Olinksy’s “Portrait of an Artist,” whether or not it was painted at the League, nevertheless demonstrate how mixed-gender classrooms strengthened the growing appreciation for Twentieth Century women as serious artists. “The League has always been a really pioneering institution when it comes to gender inclusivity,” Moerdler says, pointing out that the founding documents actually mandate it. The League’s 1875 constitution insists on the representation of women and students on its “Board of Control,” a policy that remains in place today.

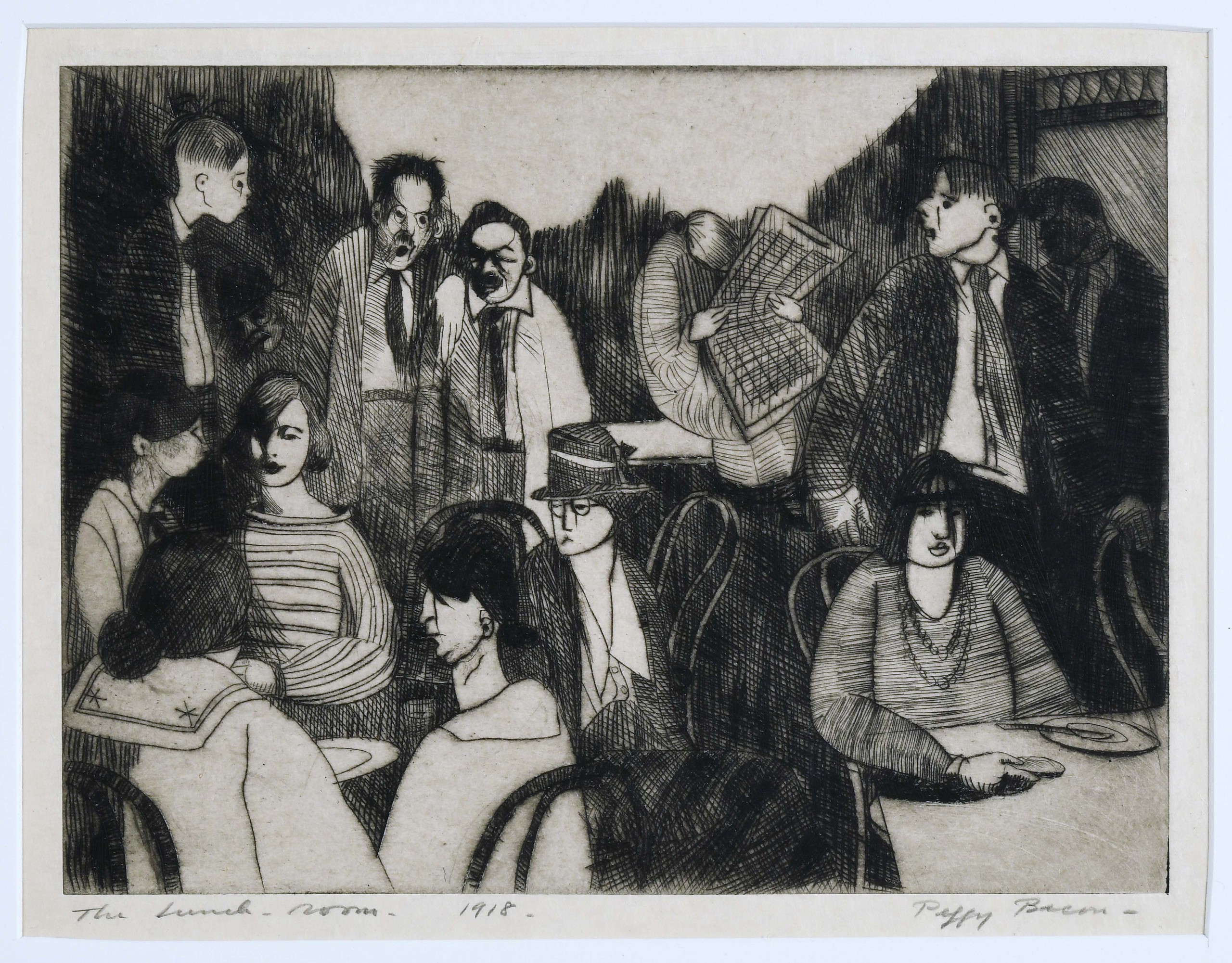

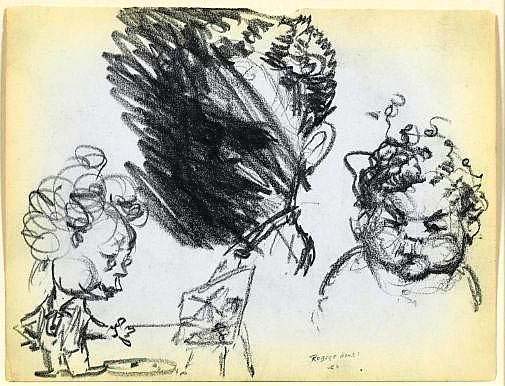

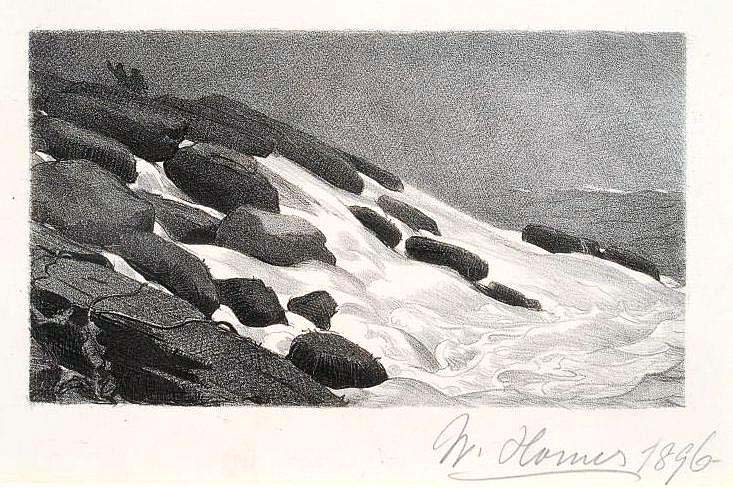

The League’s commitment to inclusivity, its willingness to break boundaries, is clearly one of its superpowers. Nouril points out that this philosophy, historically and today, extends beyond women to include queer artists, people of color and international students, and, moreover, that it extends beyond human demographics. The League also has a history of dismantling barriers between art genres, of teaching commercial art and illustration as well as painting and sculpture and exhibiting artworks like Ruth Morley’s costume designs and Stephen Cartoccio’s figurine of the rapper Notorious B.I.G. alongside portraits by Will Barnet and seascapes by Winslow Homer. “We also have very pioneering figures who represent very diverse backgrounds,” says Nouril.

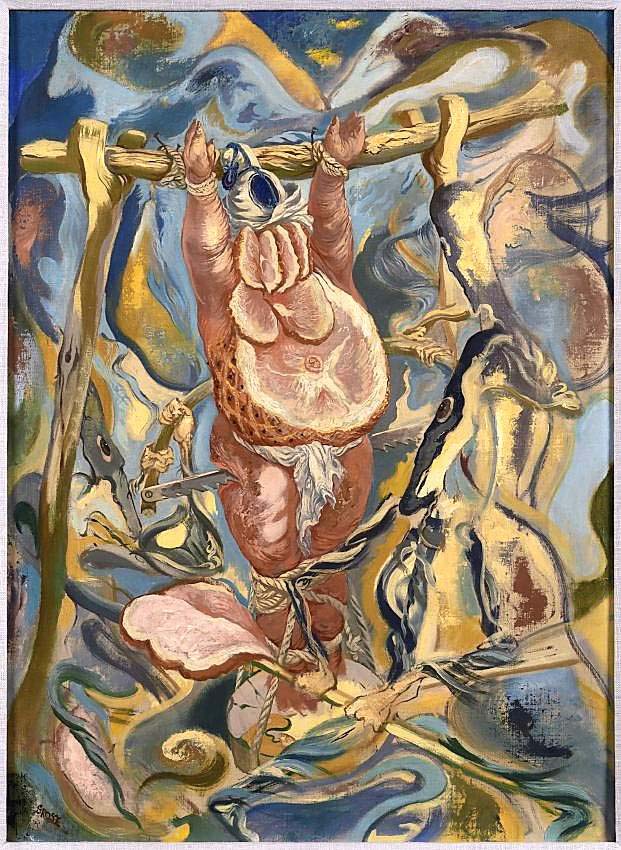

Moerdler adds that the League’s embrace of international students is an important part of the school’s history, underscored two years ago in an exhibition titled “A League of Nations.” “We really wanted to highlight people who were refugees…and found refuge in the League and [its] community.” Those folks have a place in “Shaping American Art,” too: several are in a section dedicated to works that examine war and times of national and international turmoil. Here, along with prints by Rockwell Kent and Charles Wilbert White, is George Grosz’s painting “The Crucified Ham,” which captured the violence and dehumanization that came with the Nazi takeover of Europe. Along with other League artists like Chaim Gross, Terry Haass and Alice Brill, Grosz had escaped to make a new home in New York. “There was this whole contingent who had fled Europe for various reasons and found each other at the League,” Moerdler says. She adds that the school continues its outreach to international students today, even amid the increasing complexities of attaining visas and crossing borders.

“The Crucified Ham” by George Grosz, 1950, oil on canvas, 33 by 26 inches. Permanent Collection, The Art Students League of New York, © 2025 Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Despite the progressive policies in place from its founding year, the League did not welcome Black students until 1929, as Austin Porter writes in his essay on Charles Alston, the League’s first Black instructor, in 150 Stories. Nevertheless, its commitment to offering a la carte, low-cost classes — as well as free evening life drawing sessions — meant that it was ultimately able to achieve in practice the accessibility it aspired to in theory. Nouril points to the example of Joseph Delaney (brother of Harlem Renaissance painter Beauford Delaney), represented here by a portrait of a model done at the League in the 1930s. Despite Delaney’s “ups and downs in his life,” Nouril notes, “he remained steadfast, committed to the League….He was a lifetime member and continued to attend free sketch classes…well into the 1980s.” The League also went on to hire an impressive roster of Black instructors over the years, many of whom began as students: Alston, Romare Bearden, Hughie Lee-Smith, Richard Mayhew and Norman Lewis. Jana La Brasca writes in 150 Stories that although Black painter Beverly Buchanan, known for her large-scale abstract paintings, only briefly attended Lewis’s classes (“He was the idol,” she quotes Buchanan saying), her League experience directly preceded her first solo New York show.

One of the revelations of 150 Stories and “Shaping American Art” is just how much the League’s students and instructors have, indeed, shaped art in the United States and beyond, and how much they continue to do so today. Who knew that Robert Rauschenberg took classes there, or Yayoi Kusama, or Ai Weiwei? There were even some surprises for the curators, facilitated by the League’s habitual list- and record-keeping. Moerdler explains that she and Nouril discovered the student card for Mary Wright — whose “American Modern” dish designs with her husband, Russel, were once ubiquitous in American homes — while researching another topic. When they reached out to Manitoga, the Wrights’ upstate New York home that is now a national landmark house museum, the staff there said they had never known that Wright had studied at the League.

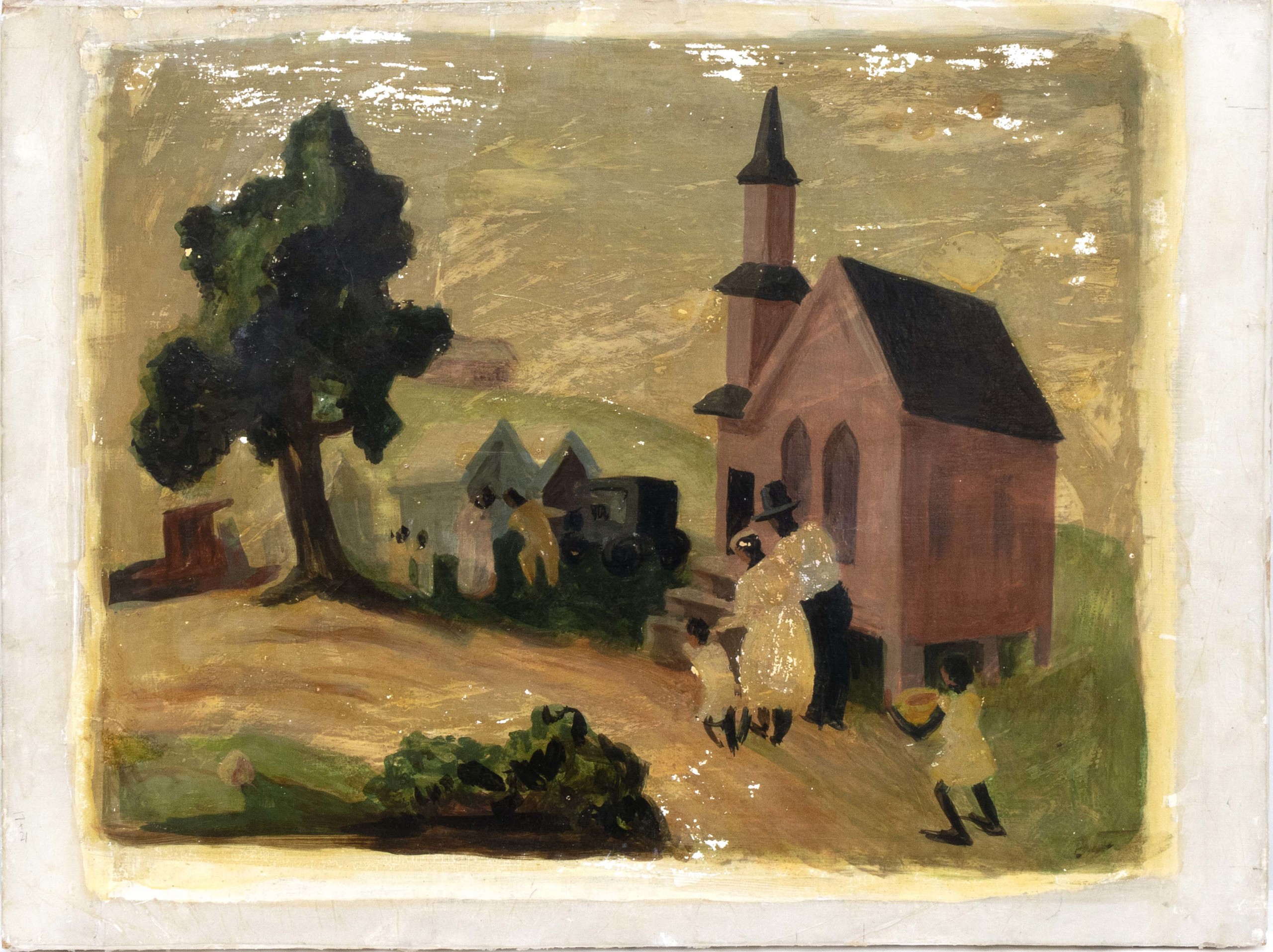

“Sunday Morning” by Thomas Hart Benton, 1934, oil on hardboard, 18 by 24 inches. Permanent Collection, The Art Students League of New York, © T.H. and R.P. Benton Trusts / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Another surprise came in the form of a package, with no return address, delivered to the League offices with an unsigned note that said “I believe this is a Thomas Hart Benton.” Reader, it was. After “peeling back the layers” of the “beautiful scene of a mother taking her child to church,” Moerdler says, they tracked down the attic in which it was found and determined through student records that the property once belonged to someone who had studied under Benton at the League and received the work from him as a gift. Cleaned, reframed and given the stamp of authenticity from the Benton catalogue raisonné project, it will be on public display for the very first time in “Shaping American Art.”

“It was never hard to work at the League or work with our collection or exhibition program,” Nouril says from her current office at the Museum of Modern Art, where she is now assistant director of the international program, “because really it was like almost an infinite number of artists could be included in our shows….Almost every institution, whether it be a commercial gallery or a nonprofit museum, has a League artist on their roster, in their collection or on rotation in some way.” Moerdler agreed, adding that in seeking out loans for “Shaping American Art,” she and Nouril often helped other organizations understand what they had to offer by cross-referencing their collections databases with the League’s student records.

In the past, the League used to include ever-changing lists of its most famous alumni in its printed course catalogues and promotional brochures. Today, research and technology have enabled it to go even deeper, for a much larger audience. Its public collections database, for example, will be overhauled for the 150th, to launch later this year. For now, “Shaping American Art,” 150 Stories and the many other anniversary offerings this year name those artists and share their stories, honoring the deep history and outsize impact of the Art Students League on the history and future of American art.

The Art Students League is at 215 West 57th Street. For information, www.artstudentsleague.org/150 or 212-247-4510.