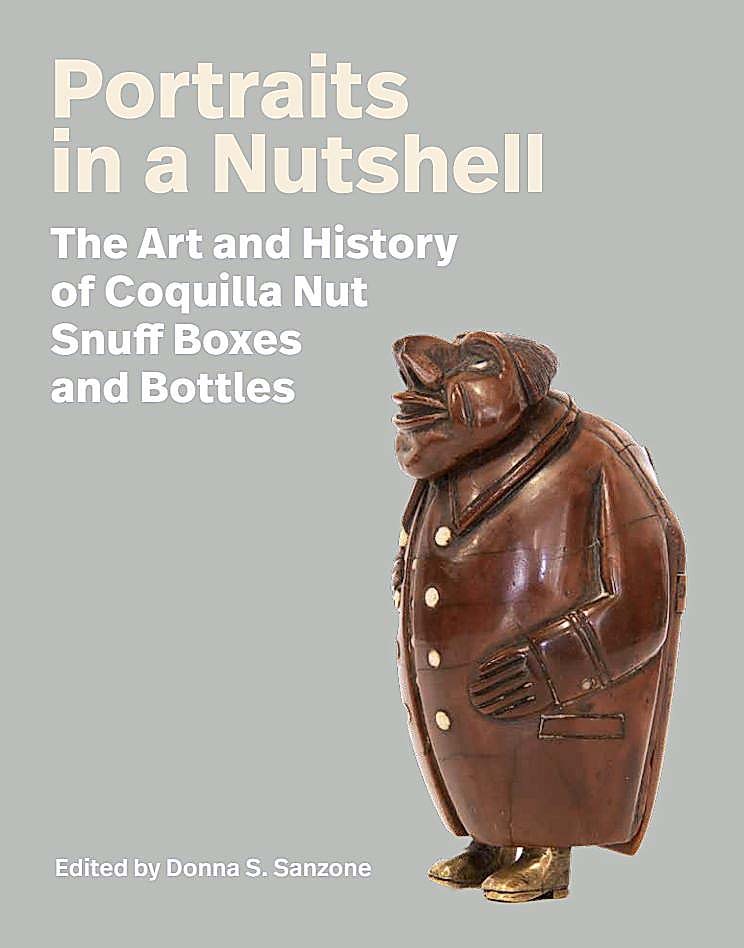

David Badger is one of the foremost collectors of coquilla nut snuff boxes and bottles. In fact, his collection is so significant that a new book — Portraits in a Nutshell: The Art and History of Coquilla Nut Snuff Boxes and Bottles, edited by Donna S. Sanzone — was published to highlight the collection and its background. We connected with Badger to learn more about his collection and the research that went into the new book.

Can you tell us a little about yourself and your background?

I am a retired businessman, having spent all of my working life associated with a major food manufacturer, Mars, Inc. My early years were focused on studying the piano at the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music and with Mdm Samaroff of Juilliard, then attending the Phillips Exeter Academy, Princeton University (BA) and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (MBA). I have spent many years outside of the United States, living in London, Vienna, Hong Kong and Tokyo. I am an active member of St Alban’s, an Anglican Episcopal Church in Tokyo.

What is the coquilla nut?

The coquilla nut is the fruit of the Bahia piassave (Attalea funifera), a species of palm tree native to the coastal region of eastern Brazil. It is a small, hard, shiny nut measuring only 3-4 inches in length.

The coquilla nuts that you collect have all been carved into snuff boxes or bottles, right? Can you tell us a little about the history or background of this practice?

Yes, the snuff boxes and bottles in my collection are carved from the coquilla nut. Early voyagers to Brazil noted that the nuts were used for rosary beads, bowls of tobacco pipes, and toys. In the early Nineteenth Century in Europe, coquilla nuts were made into small utilitarian household objects, such as nutmeg graters in the shape of acorns, egg cups, bell-pulls, as well as beaded bracelets and necklaces. Beyond its role in carving objects, the coquilla nut was also an important source of oil in the emerging European timekeeping industry. Nuts in their natural form were exported from Brazil to be processed into lubricant for precision timekeepers and marine chronometers. However, by the mid Nineteenth Century, the supply of coquilla nuts was exhausted due to overharvesting.

Coquilla nut snuff box, circa 1800, showing a well-dressed figure wearing a Brazilian Liberty Cap, possibly representing a tailor. Their dress may allude to the 1798 Revolt of the Tailors in Brazil, a rebellion named after the occupation of many of its leaders. Height: 3.8 inches.

Do the carved descriptions have greater meaning than just their forms? Are they representative of a greater belief or carry symbolism?

Yes. The snuff boxes and bottles in my collection represent not only a wide range of artistic styles and forms, but also reflect or represent the experiences, memories and/or religious, spiritual or political beliefs of their African, Indigenous, Afro-Brazilian, Afro-Caribbean or African American creators. The majority of images portray a range of people, animals and events. Other snuff box imagery utilizes visual abstraction or caricature for comedic effect, political commentary and ridicule of social mores of the time. These examples demonstrate that the artists were not only carriers of traditional values but also commentators and innovators in expressing their perspectives in the Atlantic world more broadly.

What sparked this collecting interest for you?

I have always been interested in objects made of wood, and especially those of considerable age. I was captivated by small boxes made of coquilla nuts when I first discovered their existence some 50 years ago. With a shiny patina, an almost smooth oily feel, intricate carvings and a most appealing small size, they sparked my interest immediately. Since then, I have rarely passed up any coquilla object I have found, mostly in England and France and some in the United States. My collection now numbers more than 700 pieces.

Can you pick out a few favorites from your collection?

Among my favorites: a tiny, perfectly shaped 1.9-inch elephant (the only elephant in my collection and the smallest object); Napoleon (standing in his traditional pose alongside the imperial eagle); a monkey wearing a hat; a double-headed carving of George and Martha Washington; the French warship Scipion from the Napoleonic Wars; a figure representing a Brazilian nun and martyr in the Brazilian War of Independence; a Brazilian freedom fighter wearing a liberty cap; and a snuff bottle decorated with hunting weapons and Brazilian animals.

A rare snuff box made from a small coquilla nut in the form of an elephant, with tusks made of whalebone, late 1700s. Length: 1.9 inches.

Do you collect other items with similar historical backgrounds, or related items?

I have collected “things” from very early childhood and displayed them appropriately. Small starfish found on lobster boats in Gloucester, Mass., butterflies and stamps were my early interests. Subsequently, Eighteenth Century American furniture, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century wooden snuff boxes in the shape of shoes, Eighteenth Century Grove candlesticks and silver pieces made by Hester Bateman in the Eighteenth Century, have complemented my interest in coquilla nut snuff containers.

How did Portraits in a Nutshell: The Art and History of Coquilla Nut Snuff Boxes and Bottles come to be?

I am the collector and owner of the coquilla nut snuff box and bottle collection upon which Portraits in a Nutshell was created. I am responsible for initiating the investigation of this previously unknown art form and for facilitating its publication. Conventional wisdom regarding figural coquilla snuff boxes was scarce. Edward Pinto’s bellwether book, Treen and Other Bygones (1969), was the only authoritative source, and it was that book, plus discussions with dealers, that motivated my original thinking that these boxes were carved in England, France and the Netherlands. Seeking to determine better the origin of the objects, their subjects and raison d’être, and believing that it might be possible to attribute several figures to known people of importance, I decided to commission further research into the history of snuff bottles and boxes. That I was seriously mistaken regarding the history behind the carvings was readily discerned by the discussion and analysis presented in the Portraits book.

Did you learn more about your connection through having it included in the text and collaborating with Donna Sanzone and other contributors?

My knowledge of the origins of coquilla nut snuff boxes and bottles was virtually non-existent before I approached an antiquarian who was familiar with the place and time that the objects were carved, and then I had the good fortune to be introduced to Donna Sanzone who was instrumental in continuing to research the subject and edit the book Portraits in a Nutshell. Matthew Francis Rarey and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw were major contributors in understanding the history and context of these carvings.

How has your collection influenced your understanding of Brazilian, European and African history?

My understanding of the origin of my coquilla nut pieces has enlightened my understanding of the complex histories of Brazil, Europe (particularly Portugal) and Africa — the interconnected Atlantic world in which commodities were traded for human beings for centuries. Most significantly, it increased my understanding of the history of those who were sent to Brazil to work principally on sugar plantations and in mining industries, who were seconded to whaling ships, and then to ships of war in the Napoleonic French navy who sold or traded coquilla nut objects throughout the Atlantic ports. These carved pieces tell a story that was heretofore unknown. And, in doing so, they have opened up a new chapter of events of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century at a time when knowledge and awareness of this history have become increasingly relevant to global understanding.

If our readers want to learn more about the coquilla nut snuff boxes and bottles, how can they purchase the book?

The book is available to pre-order from the Brandeis University Press website, online retailers and local bookstores. Publication date is June 27, 2025.

—Carly Timpson