Evening purse, Judith Leiber, United States, 1997, gold, metal, rhinestones. Gift of Federated Retail Holdings Inc. 2007.100.105d-h. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-092764.

By Laura Layfer

CHICAGO — When the Costume collection manager at the Chicago History Museum (CHM), Jessica Pushor, decided to take a pair of Nike Air Jordan 1 men’s basketball shoes out of collection storage and up into the galleries, she knew immediately from her colleagues’ reactions that it was a very a good choice. Selecting from the CHM’s more than 50,000 costumes and textiles, ranging in date from the Eighteenth Century to the present, was no small feat as the iconic sneakers are one some more than 70 pieces included in the museum’s current exhibition, “Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective.”

The exhibition celebrates both the centennial anniversary of this vast and important collection, as well as honors the 50th year of The Costume Council and their visionary and progressive leadership. CHM was initially founded in 1856, as The Chicago Historical Society, a repository for national, and — more specifically — local Chicago-based, history and culture. In 1871, the original building where the collection was housed was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. A 1920 purchase of the Americana and Civil War collection of Charles F. Gunther, a candy manufacturer who acquired US military clothing and ensembles with strong provenance attributed to George Washington and some that belonged to Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln, helped establish fashion at the forefront of the Society’s holdings, and ultimately that of CHM.

From then on, the use of fabric and its adornments as a mode for Chicago storytelling and civic discourse has been integral to the institution’s content and growth. In 1932, the first position for curator of costume was filled, and, in 1957, a group of women then known as The Fashion Group of Chicago, formed an alliance to promote “good taste in fashion.” They would formally transition to The Costume Council in 1974, tasked with ensuring contemporary dress remained integral to the future of the collection, and today proudly include men on the committee as well. As Pushor, who served as curator for the show explained, she wanted to examine both how and why objects were collected and provide a context to look at them outside of the limits to time period alone. The accompanying galleries are divided into five sections: “Everyday Clothing and Sportswear,” “Couture and Designer Fashion,” “Historic Clothing,” “Fashion and the Arts” and a wall of fashion illustrations.

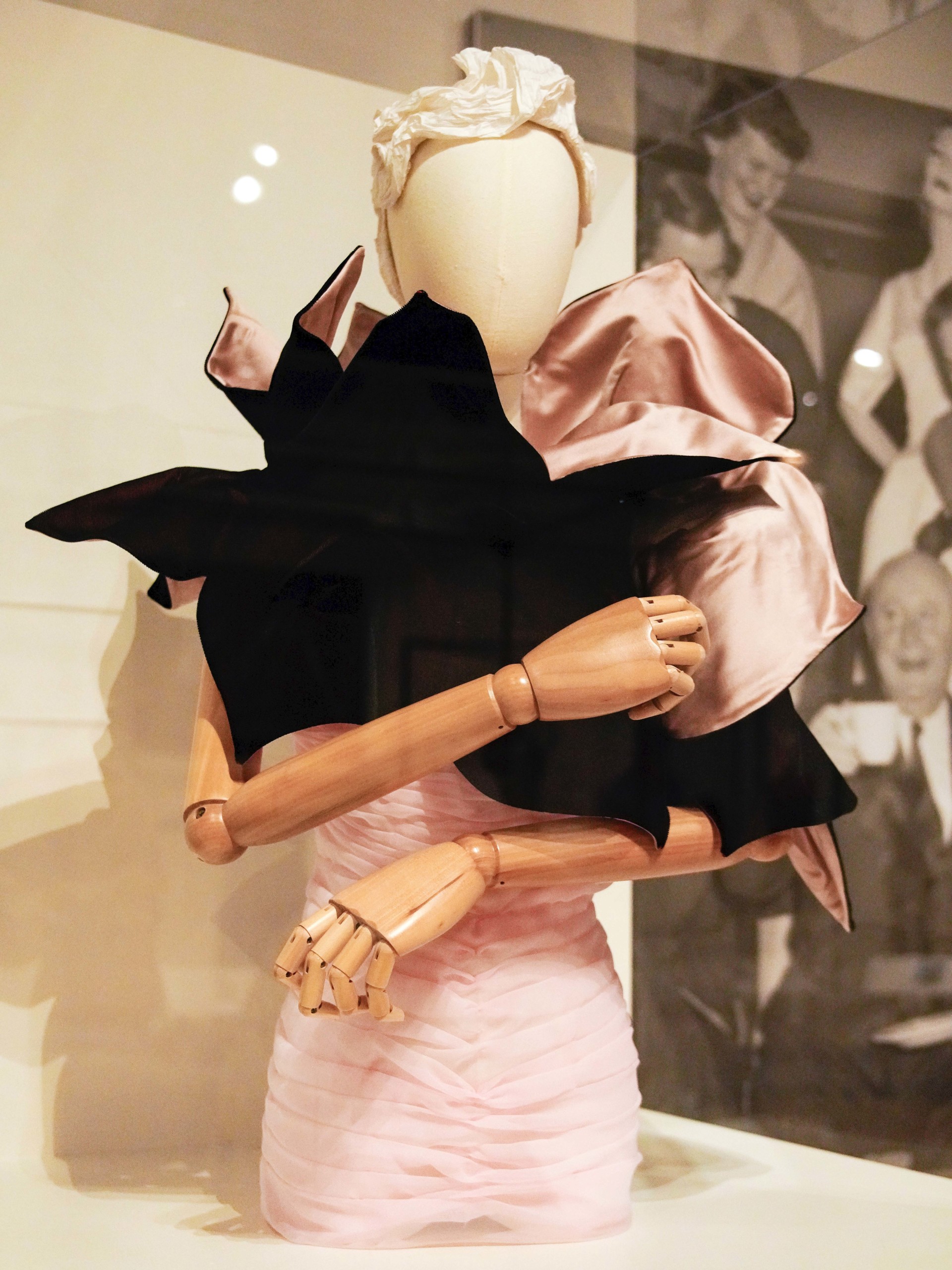

View of the “Art and Fashion” section from the “Dressed in History” exhibition, pictured is a dance costume designed by Isamu Noguchi for Ruth Page, a cape worn by singer and activist Etta Moten Barnett, a men’s burlesque ensemble, and feather fans used by infamous dancer Sally Rand. Chicago History Museum Communications department image.

To begin, Pushor reached out to all available past costume curators at CHM and asked each to pick four or five objects collected during their respective tenures that were “favorites,” with the caveat that those chosen had never been placed on public display. These former colleagues wrote essays for the accompanying catalog and discussed their experiences and reflections in that role. “I knew this was as much a tribute to my predecessors and their contributions to the collection,” noted Pushor, “and the majority of the duration spent organizing this show was during Covid, so it was a way to access individuals and information that didn’t require as much onsite research for collaboration.” The opening wall leading to the galleries offers a massive, printed timeline of CHM’s history, with a focus on its costume collection and curators. For astute visitors and researchers alike, there is a QR code available on the facade that allows people to view catalogues for CHM fashion exhibitions since 1978.

While sportswear and streetwear began to prevail in the late Twentieth Century, earlier period garments are a well-known treasure trove to fashion historians worldwide. One of the most prized is the Sorbet evening gown, designed in 1913 by French couturier Paul Poiret, and worn the same year to a Chicago debutante ball by the granddaughter of the founder of Merchants National Bank. Often referred to as the lampshade tunic due to its silhouette, it is the only known exact match to the sketch of the same year that was advertised in the Gazette du Bon Ton. The periodical is on view and shown alongside a gold silk turban adorned with lace and beads by Poiret, worn by Mrs Potter Palmer II. Like the latter, famous Chicago business titans and their families were patrons of high style American and European designers. Pushor pointed out a little girl’s dress with embroidery that came to CHM with a note stating it was made by Poiret in 1915, yet research suggests it is more likely the work of a female couturier of that era, Jeanne Lanvin. Her young daughter was frequently included at the Lanvin atelier and her mother’s muse for marketing materials and production output.

Fidélité dress, Christian Dior, France, autumn/winter 1949, silk, nylon. Gift of Mrs Jeanne B. Heinzelman. 1983.28.1. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-179996.

It was not uncommon for couturiers like Poiret to choose Chicago as a destination. Following his visit in 1913, the Chicago Daily Tribune headline read: “Poiret Startles Chicago Women… Modistes Scoff at Frenchman’s Views; Say His Shades Are Too Daring.” In 1947, Christian Dior made the pilgrimage because the department store Marshall Field & Company was one of his biggest clients. Out of that relationship, CHM retained hundreds of Dior items in their collection, including an exquisite 1950s glass and metal necklace on display and from the house’s costume jewelry collaboration with Henkel and Grosse. Nearby, more accessories sparkle, as a Judith Leiber green, white and black Swarovski crystal evening bag takes the shape of Marshall Field’s symbolic clock, located atop its flagship store exterior on Chicago’s legendary State Street. A 1960s deep shimmery green silk evening dress by Cristóbal Balenciaga is cut with a fitted long bodice and layered ruffles accented with bows at each hip. It was a gift of Mrs Jay Pritzker, and retailed at Stanley Korshak, a luxury goods store that began with its namesake in Chicago, before the retail venue moved to Dallas, where it still operates.

The early collection days were no doubt filled with plenty of the usual suspects familiar to community donations, including homemade children’s wear and wedding gowns passed over generations. Sometimes, as Pushor said, the anecdote of an object’s arrival is as enchanting as its own adornment. An Eighteenth Century stenciled and embroidered robe à la française gown made its way to CHM in 1920 with the Gunther Collection, and the provenance of having been worn by Queen Caroline of the United Kingdom. Later, when that affiliation could not be verified, the CHM deaccessioned the piece in a rummage sale. In 1926, politician and socialite Bertha Bauer bought the dress (Pushor said that as the story goes Bauer was first in line at the sale that morning) for $150 (equivalent to approximately $2,500 in 2024) and wore it to many fancy affairs around town. In 2016, almost a century later, Bauer’s granddaughter re-donated the gown to CHM. Its condition is impeccable, and, as a special addition to this exhibition, CHM asked an embroidery expert to digitize the details of the design, now available online for individuals to download and recreate their own historical dress or textile.

Robe à la française, unknown maker, England, 1740-1775, silk. Gift of Romia Bull. 2016.439.a-b. Chicago History Museum Communications Department image.

In another twist of fate, the Nike Air Jordan sneakers were purchased by CHM staff in 1987, on sale for $34.99, at Carson Pirie Scott & Company, then a popular Midwest department store. “They were only bought because the red and black colors matched an ensemble by the late fashion designer Willi Smith and we needed shoes for the mannequin,” laughed Pushor, noting the kicks were simply affordable and readily available retail. Now they sell at auction for thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars, but back then Michael Jordan was still a Chicago Bulls rookie. “School kids come through here and just stare in awe,” said Pushor, “and the day I unpacked them all of my colleagues came over to catch a glimpse and reminisce about our hometown NBA basketball legend.”

Funding from The Costume Council helped to designate designer access with one of their initiatives being the presentation of a “Designer of Excellence Award.” Previous honorees have been James Galanos, Sonia Rykiel, Bill Blass, Christian Lacroix and Carolina Herrera, to name a few recipients. Relationships with designers around the globe have been pivotal to CHM’s success in building their collection. A black wool dress suit with allover red hearts, stars and lips was a gift to Dorothy Fuller, director of the Chicago Apparel Center, from Patrick Kelly. He was a Black American fashion designer, and when his friendship with Fuller began after the two met in Paris, she continued to promote his work throughout Chicago and facilitated Kelly’s visit to work with students at the International Academy of Merchandising and Design.

Similarly, in 1986, Italian designer Gianni Versace opened his first US based store on Chicago’s famous Oak Street, renowned for its high-end boutiques. “He was very generous to the Museum,” said Pushor, “Versace visited the collection and afterwards donated several pieces from his menswear and womenswear collections that year.” A sleek gray and black cashmere and silk gentleman’s suit on display was part of that fall/winter 1985-86 season; known as “The Klimt Collection,” it had been created in colors, patterns and textures that were inspired by the work of the Austrian artist Gustav Klimt.

Women’s suit, Patrick Kelly, France, circa 1988, wool. Gift of Ms Dorothy Fuller. 2008.174.1a-b. Men’s suit, Gianni Versace, Italy, fall/winter 1985-86, cashmere, wool, cotton, silk, leather. Gift of Gianni Versace. 1986.201.5a-e. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-179321.

The relationship between fashion and art in various disciplines remains critical to CHM’s mission for civic discourse. One of Pushor’s personal favorites in the exhibition is a 1930s woman’s dance costume, a wool sack dress designed by Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi and worn by ballerina Ruth Page for many of her performances. Other societal messages such as gender roles are considered in the presentation of designer Rudi Gernreich’s black wool bathing suit from the 1960s. It is written in the exhibition catalog, “[he] wanted his ‘monokini’ to be a visual confrontation of double standard of female nudity versus that of men in public spaces,” and a model wearing the topless swimsuit in June 1964, on Chicago’s North Avenue Beach, was arrested for her indecent exposure.

Provocative and daring seem to be part and parcel with Chicago’s relationship to fashion. Whether more classic as in the surrealist-like silk petal stole by Charles James, who began his career in the 1920s as a milliner in Chicago before becoming one of the most celebrated couturiers of the Twentieth Century, or more cutting-edge as in current local female fashion designer Maria Pinto’s nylon two-piece day suit meant to mirror the shape of another modern day local female’s work, architect Jeanne Gang’s Aqua building, and coinciding with Chicago’s inaugural Architecture Biennial in 2015. Fashion takes center stage at CHM because, as Pushor wrote in her catalog essay, “more than any other type of artifact, clothing is an object to which everyone can relate.”

“Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective” is on view at the Chicago History Museum until July 27.

The Chicago History Museum is at 1601 North Clark Street. For information, www.chicagohistory.org or 312-642-4600.