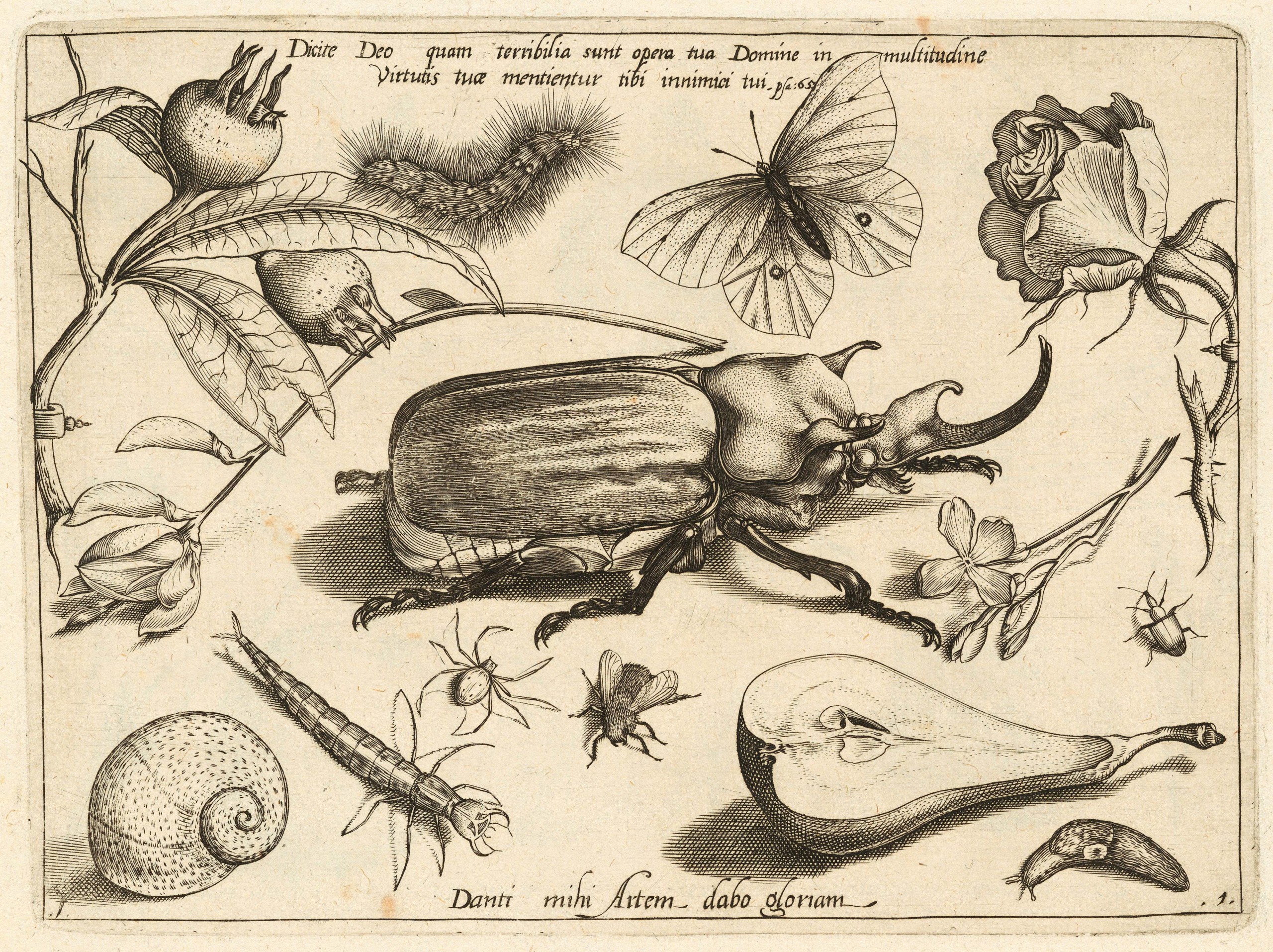

“Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary” by Jan van Kessel the Elder (Flemish, 1626-1679), 1653, oil on panel, overall: 4½ by 5½ inches. National Gallery of Art, The Richard C. Von Hess Foundation, Nell and Robert Weidenhammer Fund, Barry D. Friedman and Friends of Dutch Art.

By Carly Timpson

WASHINGTON, DC — When discussing the Old Masters, most conjure rich images of portraiture, religious and allegorical vignettes and atmospheric landscapes. However, the National Gallery of Art’s latest exhibition holds a magnifying glass over a lesser-recognized category of European works from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. “Little Beasts: Art, Wonder and The Natural World” explores art’s influence on natural history, showcasing prints, drawings and paintings from the National Gallery alongside objects and specimen from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH).

In response to advancements in scientific technology, trade and colonial expansion in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, naturalists were able to study previously unknown or overlooked species of animals, insects and other beestjes, or “little beasts” in Dutch, which led to European artists helping to spread the knowledge by creating highly detailed works of these little beasts, thus inspiring generations of artists and naturalists and awakening a new dawn in studying science and natural history. As such, in the early modern period, art and science went hand-in-hand, with one complementing and informing the other.

“Through their work, artists have always helped us make sense of the world,” said Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery. “‘Little Beasts’ gives us the chance to examine how the curiosity of artists helped to advance discovery in the study of the natural world. It is only fitting that we explore this rich exchange of ideas with our neighbors at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Delightfully detailed drawings, prints and paintings invite art lovers of all ages to marvel at these artistic feats and to explore our wondrous word.”

Megasoma elaphus (Elephant Beetle), unknown, Loan courtesy of National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

The exhibition’s curatorial team — Stacey Sell, associate curator of Old Master drawings; Brooks Rich, associate curator of Old Master and Nineteenth Century prints; and Alexandra Libby, senior administrator for collections and initiatives — shared that inspiration for the show came from the National Gallery’s permanent collection. “Joris Hoefnagel’s Four Elements volumes (containing approximately 270 meticulous studies of animals) are treasures of the Gallery’s drawing collection. Scholars come from all over the world to view the series in our study room, but Hoefnagel’s miniatures are so delightful and so beautifully painted that they appeal to almost everybody who sees them.” As such, Sell had “long hoped to find an opportunity to highlight these inherently fragile and rarely exhibited works, placing them into a wider cultural context and highlighting new discoveries about their production. Then, in 2018, the Gallery acquired ‘Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary’ by Jan van Kessel, a Flemish painter who carried forward Hoefnagel’s legacy as an artist looking closely at the animal world into the mid Seventeenth Century.” After this acquisition, the Gallery’s related collection was strengthened to six works, and Sell and Rich began to plan a way in which to bring these artists into conversation.

The team continued, “While previous exhibitions have broadly explored the relationships between art and natural history, this exhibition is unique in highlighting rarely-exhibited works by Joris Hoefnagel and Jan van Kessel as related case studies. The show aims to shed light not only on their motivations for producing these works but also on the materials and techniques that allowed them to capture the natural world in such vivid detail. For the National Gallery, the inclusion of natural history specimens in conversation with works of art was novel ground.”

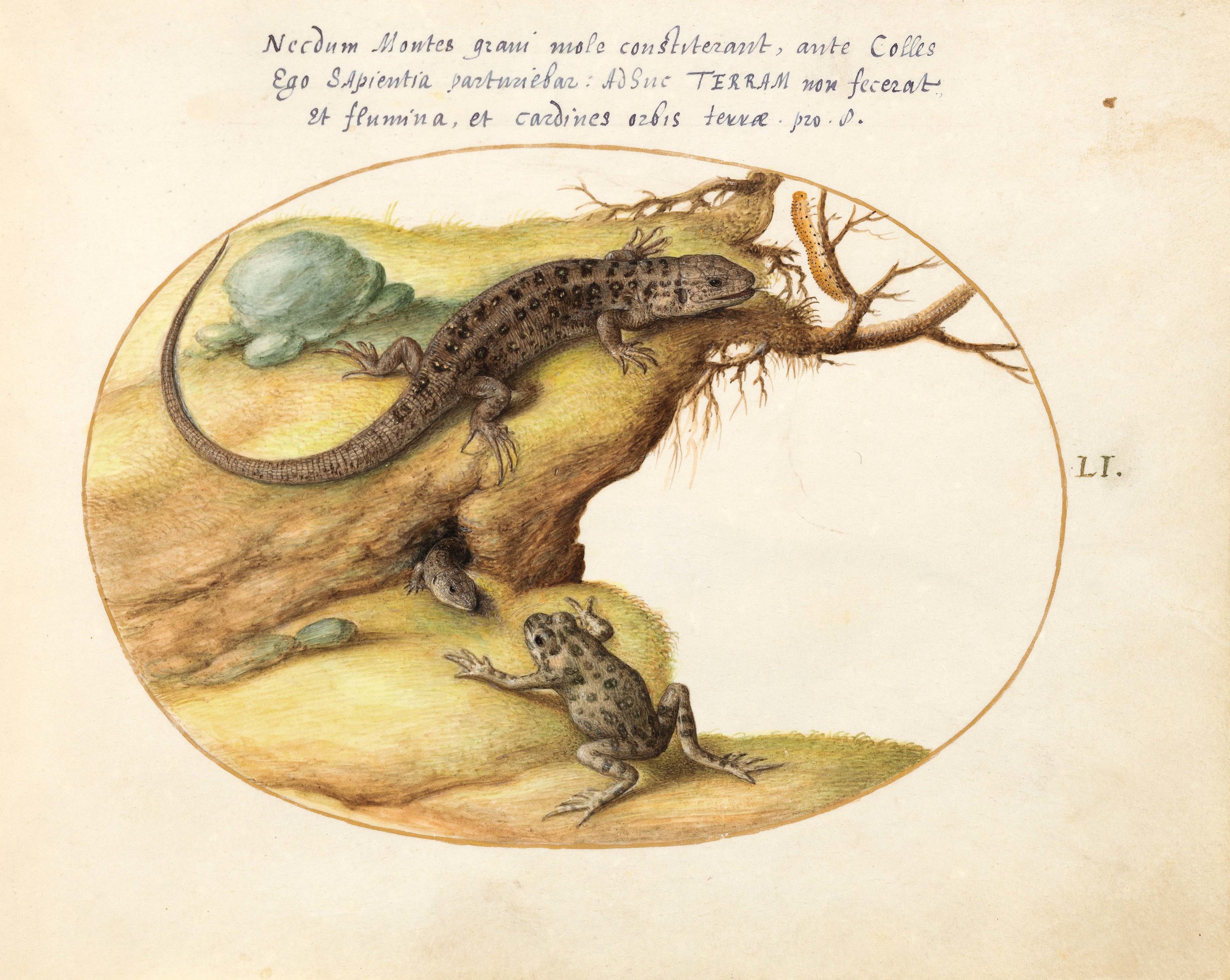

“Two Sand Lizards, a Common Parsley Frog(?) and a Caterpillar,” plate 51 from The Four Elements: Terra by Joris Hoefnagel (Flemish, 1542-1600), circa 1575-90s, watercolor and gold paint on parchment, page size (approximate): 5-5/8 by 7¼ inches. National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs Lessing J. Rosenwald.

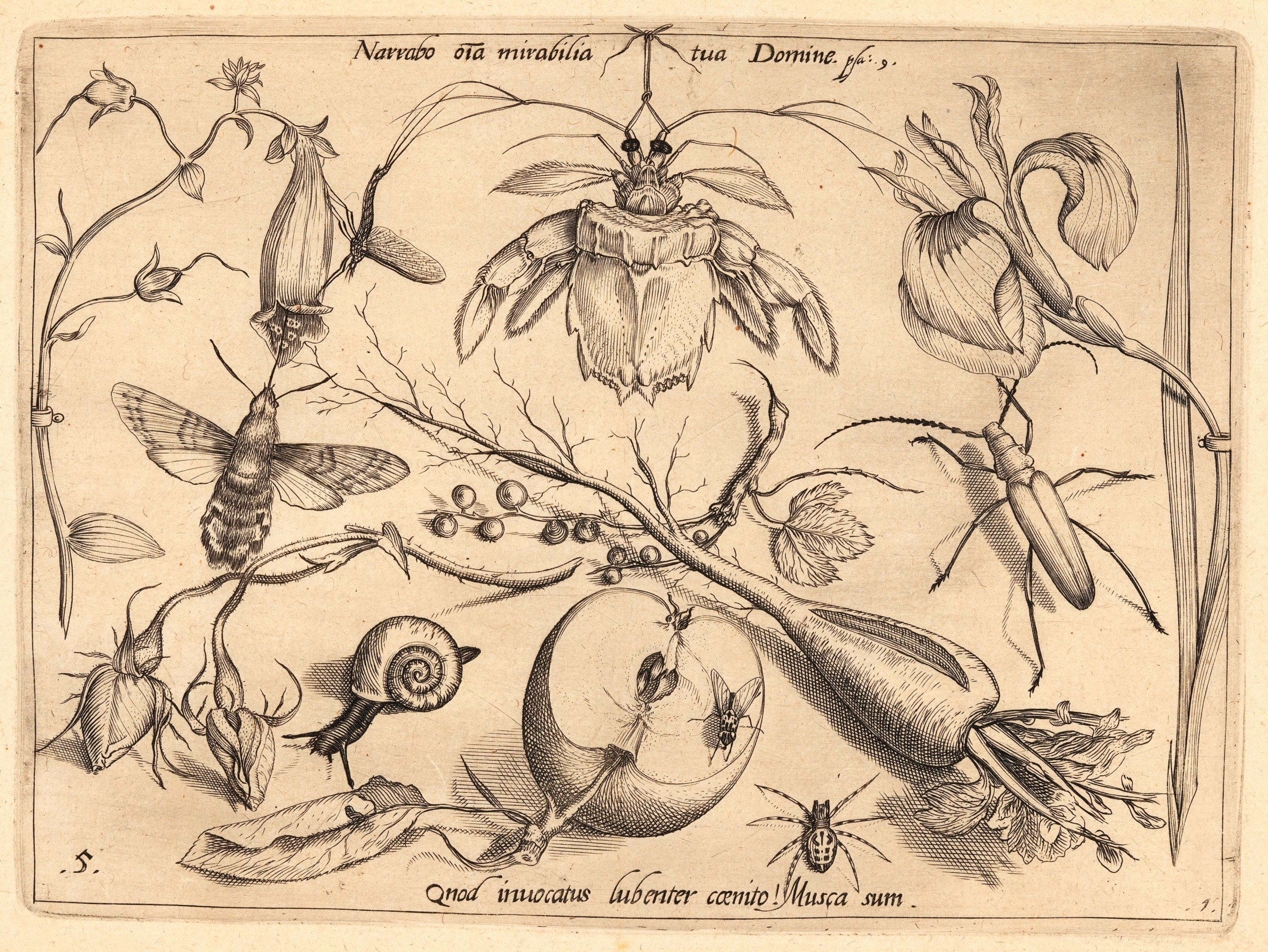

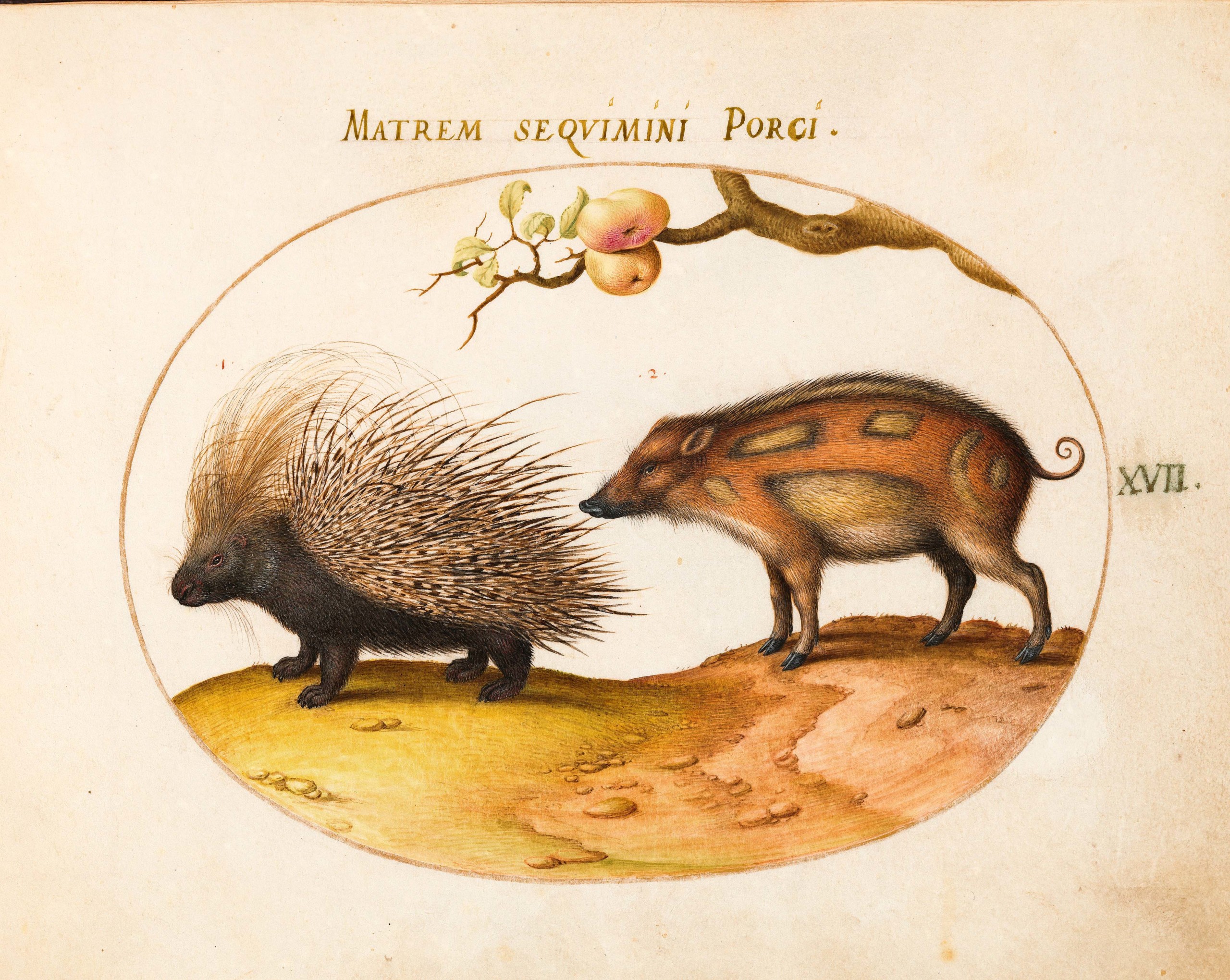

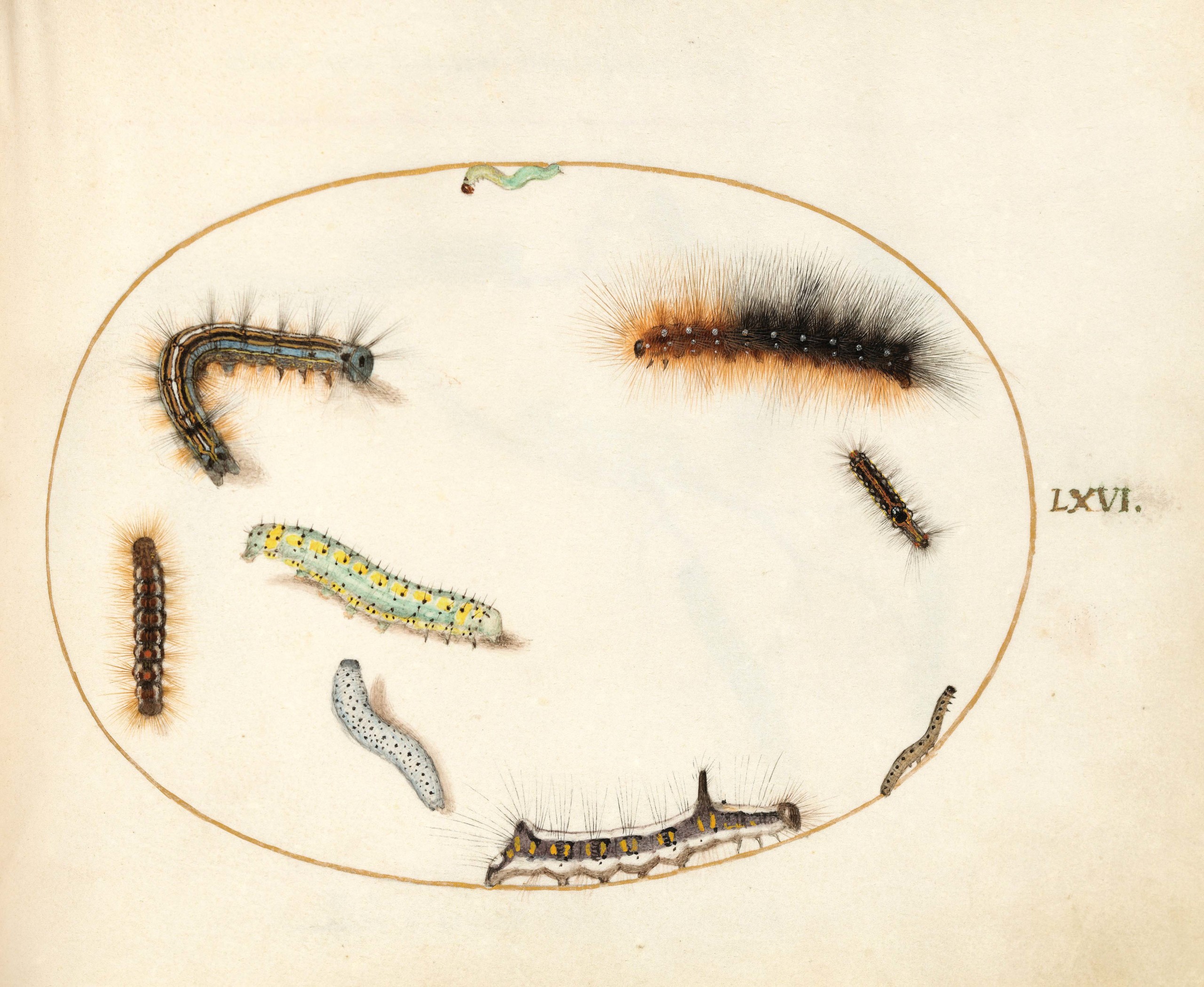

The centerpiece of the exhibition, Hoefnagel’s The Four Elements volumes — Ignis (Fire), Terra (Earth), Aqua (Water) and Aier (Air) — will be featured in four rotations, with the pages turning to showcase different plates during each run. Despite his history of creating fantastical creatures in some of his other works, in The Four Elements, Hoefnagel recorded accurate versions of real species, with a few exceptions as identified by NMNH scientists, and he went into painstaking detail to depict them as genuinely as possible. The curatorial team noted, “Four Elements is a landmark in early nature painting. Ignis, the volume devoted to insects, is especially notable as one of the earliest sustained studies of insects, admired by other artists and naturalists alike. Hoefnagel developed some innovative techniques to convey the intricacy of the creatures he studied, and we explore those in the exhibition. Because of their rarity and fragility, the volumes are not on permanent display and access to them is limited. We will turn the pages of the books three times during the course of the exhibition, and we are reuniting them with a watercolor of turkeys that was removed from the volumes centuries ago. This will give the visitors a rare opportunity to see as much of the series as possible.” The volumes, which are comprised of 270 watercolors accented with gold leaf, were originally in Emperor Rudolf II of Austria’s private collection and is almost never on view due to its sensitivity to light. Alongside The Four Elements will be related artworks and examples of the specimens depicted in Hoefnagel’s pages.

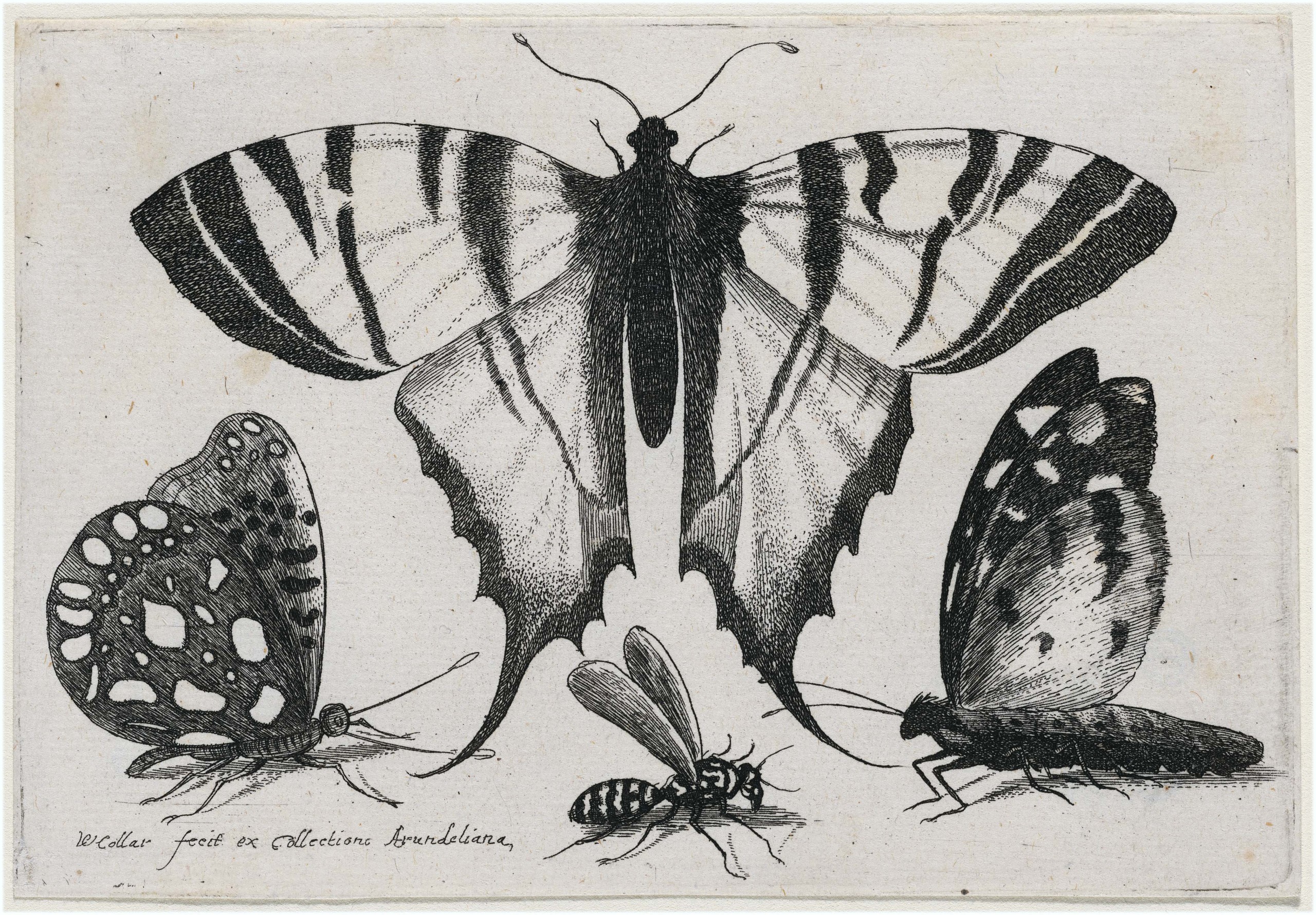

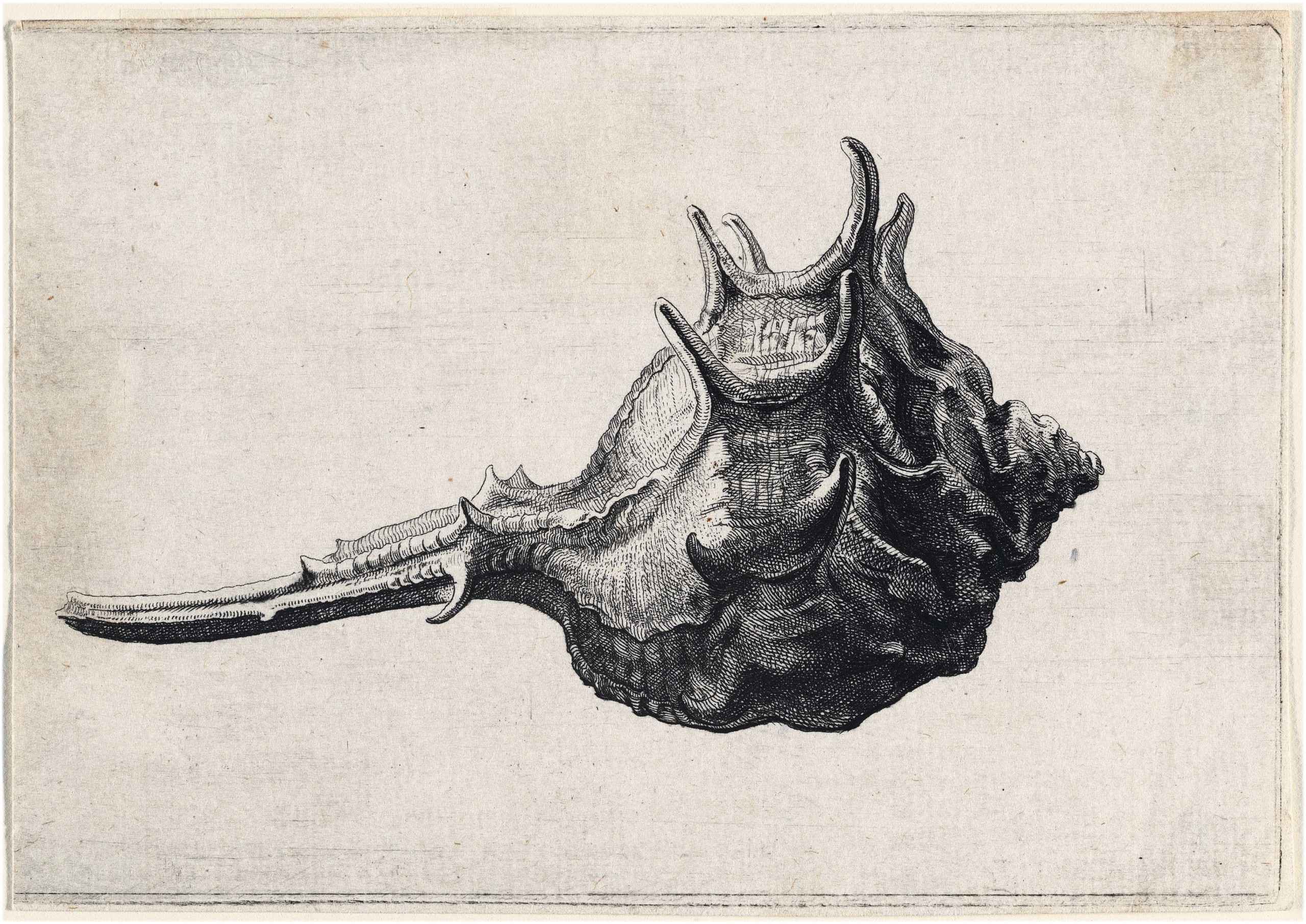

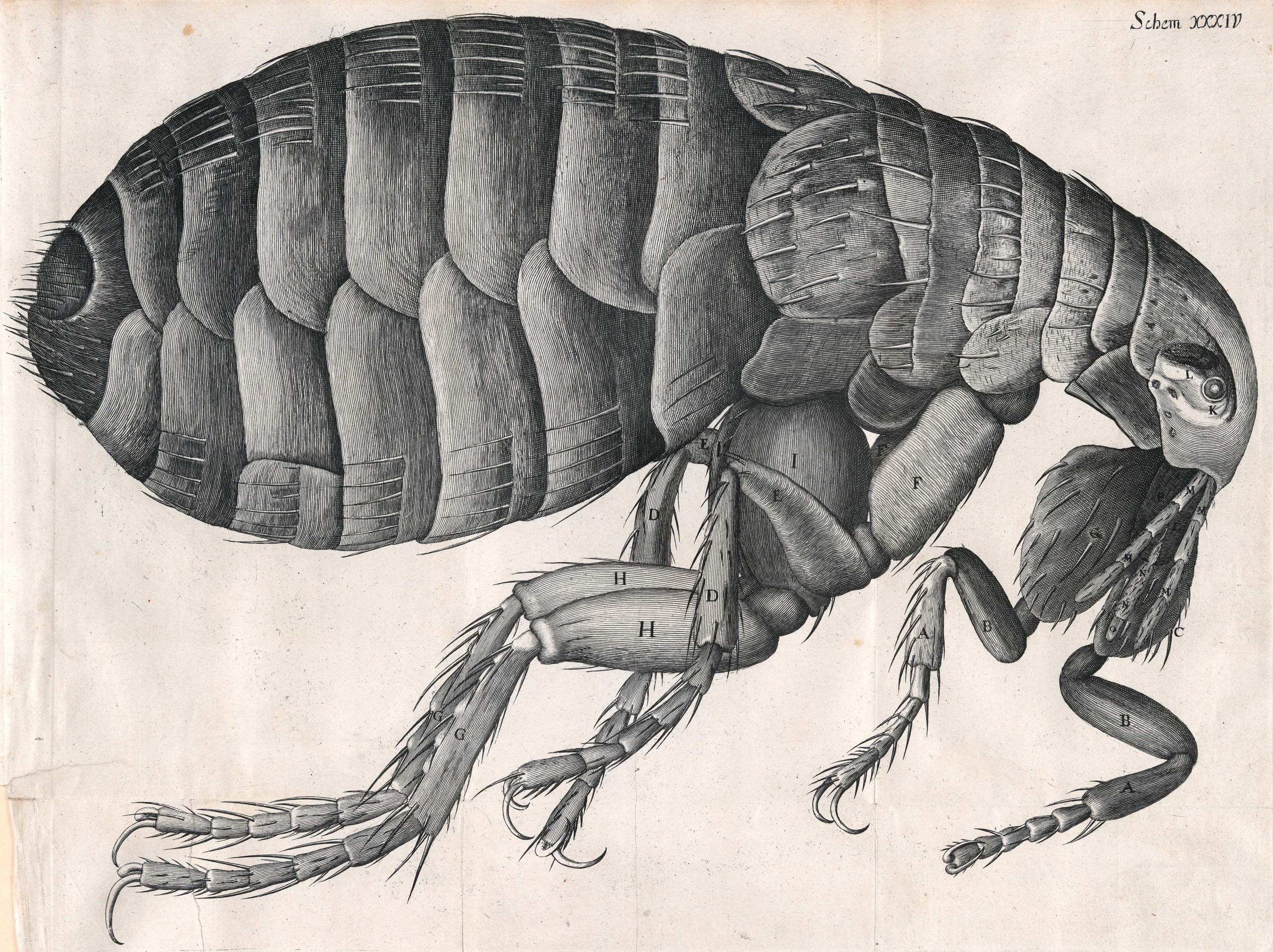

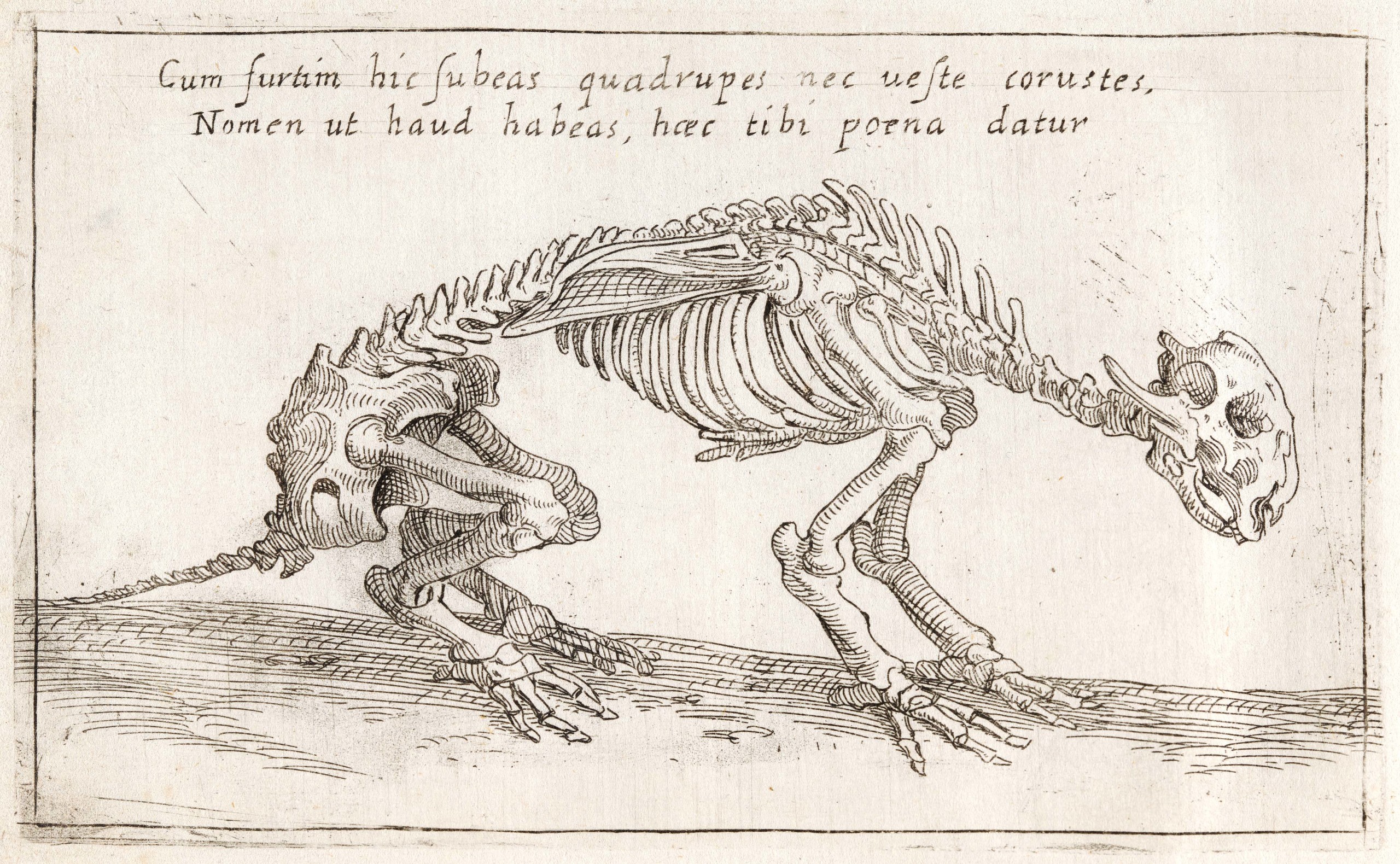

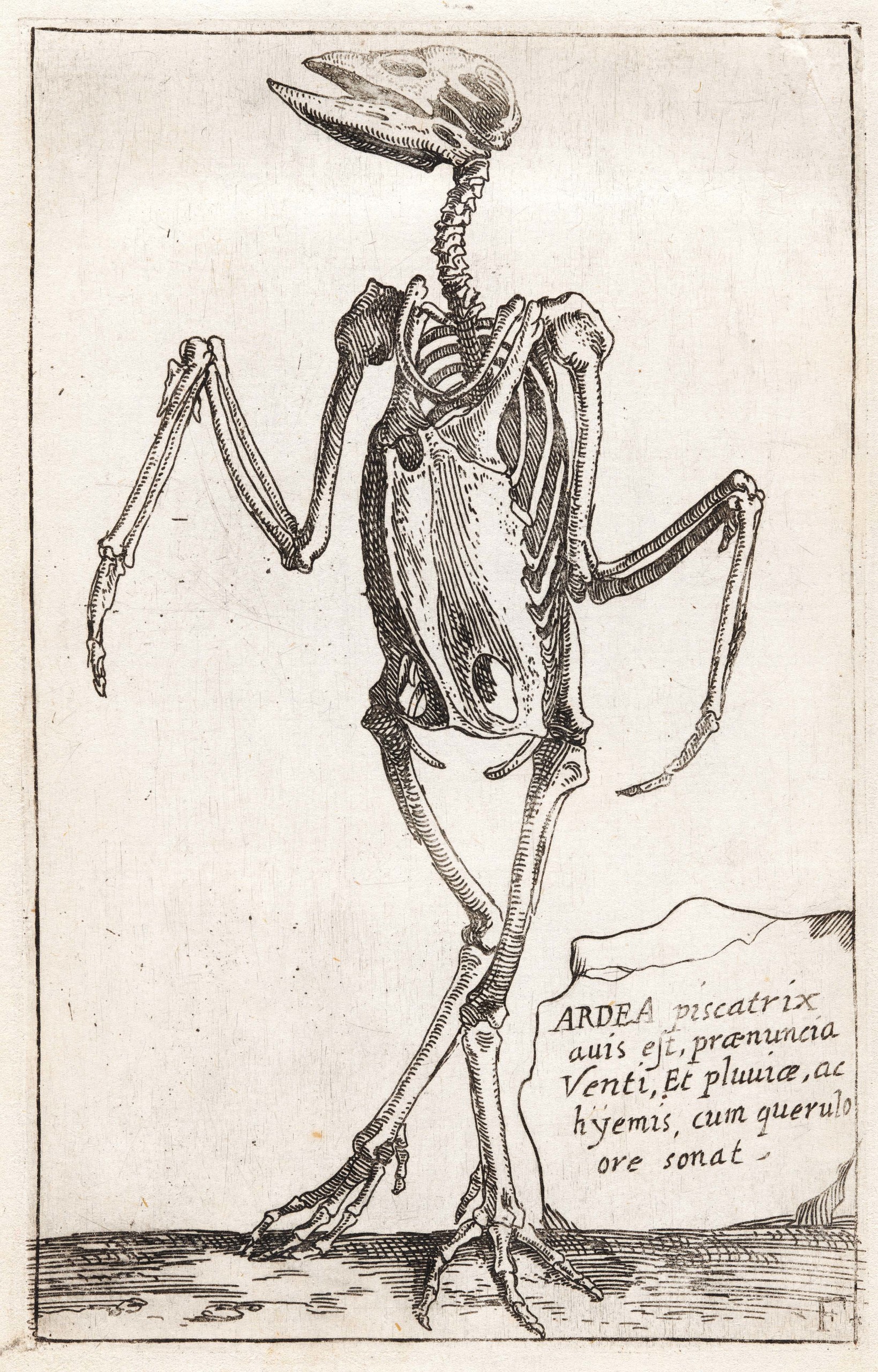

The second section of the exhibition, focused on the practice of printmaking, will highlight the developments that ensured a wider breadth of knowledge among scientists, artists and the common civilian alike. “Etchings, engravings and woodcuts all played important roles in science and technology. Living in a time when we are constantly surrounded with images, it’s easy to lose sight of how crucial printmaking was in the spread of accurate information. The ability to print and disseminate hundreds of identical images revolutionized fields from natural history to anatomy and beyond. The second section of the exhibition focuses mostly on fine prints that allowed little beasts to multiple and crawl out into the world as sources of both information and entertainment,” added the curators. Again, items from the NMNH accent these prints, inviting visitors to compare and contrast the art and the representative natural history specimens; for example, a Eurasian hoopoe is featured in relation to Adriaen Collaert’s circa 1600 “Hoopoe and Owl” from Avium Vivae Icones (Living Images of Birds).

“Hoopoe and Owl” from Avium Vivae Icones (Living images of birds) by Adriaen Collaert (Flemish, 1560-1618), circa 1600, engraving on laid paper, plate: 5-3/16 by 7½ inches. National Gallery of Art, Gift of The Circle of the National Gallery of Art

Jan van Kessel is celebrated in the exhibition’s third section, with his paintings displayed alongside prints, books and animals that inspired his work. At its apex is “Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary” (1653), which has been carefully dissected by NMNH scientists who were able to identify each species and create their own specimen tableau, including butterflies, beetles, bees moths and other “little beasts,” to show the real-life version of Van Kessel’s painting for viewers to examine. The Oak Spring Garden Library (Upperville, Va.) contributed to this section with the loan of an intact suite of 16 of Van Kessel’s postcard-sized paintings, including one in which he signed his name using various caterpillars, snakes and other creatures to form the letters. “The paintings on loan from Oak Springs Garden Library (OSGL) are one of a few extant sets of work by Van Kessel. His paintings were originally intended to decorate the doors and drawers of kunstkasten, or art cabinets. There are no kunstkasten with paintings by Van Kessel extant today, all apparently having been disassembled for the sale of their constituent parts. However, the set at OSGL allow us to imagine what such a group would have looked like together.” Additionally, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore has loaned a monumental Van Kessel painting, “Noah’s Family Assembling Animals Before the Ark.”

Commissioned as a coda to the exhibition is Until We Are Forged: Hymns for the Elements, a film by Dario Robleto. In the 40-minute film, Robleto explores the humanity that has intersected and connected art and science throughout history. Site-specific filming, historical footage, animations and an original score all work together to link the works of Hoefnagel and Van Kessel “to the efforts of modern-day conservators and image scientists at the National Gallery, who are responsible for preserving these valuable works of art for future generations,” according to the curators.

National Museum of Natural History’s recreation of Jan van Kessel the Elder’s “Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary.” Loan courtesy of National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Beyond the simple enjoyment of the art’s beauty, the curatorial team hopes for visitors to discover the joy of close looking. “We’ve included materials, magnifying glasses, interactive interpretive elements and specimens and taxidermy all to invite our visitors to engage more deeply with the artworks on display and to appreciate the art of nature and the nature of art.” In collaborating with the NMNH, the National Gallery is able to foster a technical and more hands-on experience that is not typically seen at art museums, and the exhibition urges visitors to spend time with these side-by-side comparisons to appreciate the technical innovations of the artists and the care that they exhibited for their subjects in their attention to minute details.

The curators concluded, “The amount of attention these artists lavished on insects is inspiring. It’s a great reminder of the beauty and variety of these ‘little beasts,’ especially as we read more and more about the decline in some insect populations. On a broader level, the exhibition encourages people to look closely at the natural world and to feel the same wonder and curiosity demonstrated by the artists.”

“Little Beasts: Art, Wonder and the Natural World” is on view May 18 through November 2 at the National Gallery of Art at Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue Northwest. For information, www.nga.gov or 202-737-4215.